Children play ‘Pacific Blue Marble’, a Pacific Islands edition of a popular Korean board game, to promote public awareness ahead of the 2023 ROK-PIF Summit in Seoul. Credit: Do Joon-seok, Seoul News, https://go.seoul.co.kr/news/newsView.php?id=20230511010013.

Introduction

U.S.-China strategic competition has expanded into the Pacific Islands. The competition for influence is playing out across a vast region which covers 20 percent of the earth’s surface and encompasses the 18 members of the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) as well as various U.S., French, and UK overseas territories. In recent years, China has tried to turn its growing economic presence across the ‘Blue Pacific Continent’ into strategic influence by convincing countries to switch diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China.1 China has also signed new security and policing agreements with countries such as the Solomon Islands and it tried to sign a Pacific-wide security deal with 10 islands countries in 2022 2 This has sparked a pushback by the region’s traditional security partners and major development donors. Against this strategic backdrop, the Republic of Korea has begun to articulate its own Pacific Islands strategy.3 These efforts included the Yoon Suk Yeol administration hosting the 1st Korea-Pacific Leaders’ Summit in Seoul on May 29, 2023.4 How much progress has been made, and how can the ROK more effectively cooperate with the diverse countries and territories of the Pacific Islands?

This Asan Issue Brief contextualizes the Yoon administration’s Pacific Islands engagement and assesses its impact and future prospects. The Issue Brief proceeds as follows. First, it provides an overview of the ROK’s engagement with the Pacific Island countries. Second, it discusses the emerging drivers for cooperation, including burden-sharing with the ROK-U.S. alliance, cooperation with like-minded partners, and efforts to enhance national status. Third, it reviews the achievements and performance of the ROK’s own Pacific Islands engagement. Fourth, it considers how the ROK can maximize its limited resources to make a tangible contribution to the security and prosperity of Pacific Island countries by cooperating with the United States and key strategic partners, including Australia, New Zealand, and Japan. The Issue Brief argues that while the ROK should continue to build its own unique relations throughout the Pacific Islands, ROK contributions can also be a ‘force multiplier’ together with its key allies and partners. Cooperation with the United States could focus on Micronesia, with Australia on maritime security capacity building, with New Zealand on health and skills training, and with Japan on development assistance and disaster response.

1. Background to the ROK’s Pacific Islands Engagement

ROK engagement with the Pacific Islands dates to Japanese colonial era labor migration schemes which saw thousands of Koreans work on plantations in places such as Hawaii and Palau. Saipan and Guam in Micronesia remain popular travel destinations for Korean due to proximity, with over 3,000 residents of Guam people, or 2.2 percent of the population, of Korean ancestry.5 Yet ROK diplomatic, economic, and security engagement with the Pacific Islands is relatively recent when compared to other extra-regional countries.

Unlike fierce China-Taiwan competition for diplomatic recognition among Pacific Island countries, inter-Korean competition largely bypassed the region throughout the Cold War due to the lack of communist regimes which meant that the DPRK never established diplomatic missions in the region. Instead, ROK interest in the Pacific Islands has mostly been limited to its deep-sea fishing fleets operating in the South Pacific, DPRK missile threats to U.S. forces based in Micronesia such as Guam, DPRK sanctions evasion by using Pacific Island countries’ flags for shipping,6 seeking Pacific Islands votes on DPRK resolutions in international bodies such as the United Nations, and tourism.7

Map 1. Members of the Pacific Islands Forum

(Note: associate members and observers included in white)

Source: Map adapted from the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat

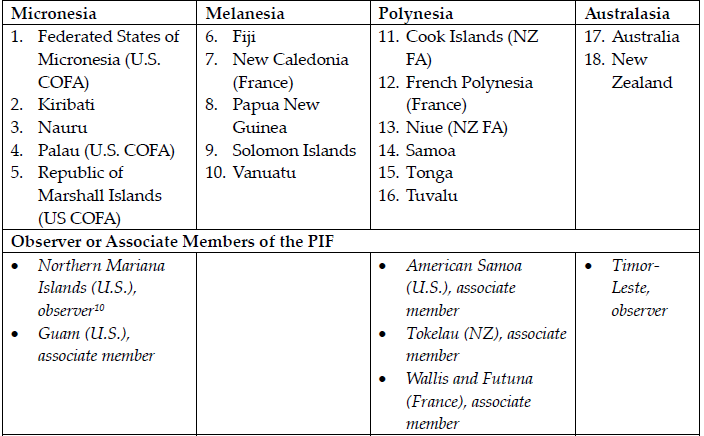

Founded in 1971, the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) is the peak organization representing 18 official members from across Micronesia, Melanesia, Polynesia, as well as Australia and New Zealand. It also includes several associate members and observers from territories which have sovereignty-sharing arrangements with other countries (see Table 1).8 The ROK joined the PIF as a Dialogue Partner in 1995, and there are now 21 Dialogue Partners.9 Most ROK official engagements with the PIF were at the deputy minister level, including four foreign minister level meetings since 2011. This was in contrast to the leader-level engagement that other countries such as Japan and China, have devoted to the region over the past decade, excluding Australia and New Zealand. For example, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Chinese Premier Li Keqiang made official visits to PIF countries and even President Xi Jinping visited Fiji in 2014 and Papua New Guinea in 2018. By contrast, no ROK president has ever visited the Pacific Islands on an official visit, with the exception being multilateral summits hosted in the region such as the 2018 APEC Summit in Papua New Guinea.

Table 1. Pacific Islands Forum Official Members by Subregion

*COFA: Compacts of Free Association; FA: Free Association

2. Drivers for ROK Pacific Islands Engagement

Why is the ROK suddenly becoming interested in the Pacific Islands and why did it host the first Korea-Pacific Leaders’ Summit in 2023?11 After all, the key economic and energy drivers of ROK engagement with other regions, such as Southeast Asia and the Middle East, do not exist in the case of the Pacific Islands. Most of the PIF countries are still developing economies. For example, total two-way trade between the ROK and the PIF countries excluding Australia and New Zealand is in the millions of dollars. By comparison, the ROK’s annual two-way trade with Australia was AUD$77.6 billion in 2022-2312 while two-way trade with New Zealand was NZD$8.5 billion in 2023.13 Some PIF countries also require substantial economic investment and humanitarian development assistance, but ROK Official Development Assistance (ODA) has historically not focused on the region. The rise of China’s economic and security influence across the Pacific Islands is similarly not viewed as a direct threat to ROK interests. Even the need to gain diplomatic support at international organizations is not a major consideration given that some Pacific Island countries do not have voting rights as overseas territories of other states.

Rather, there are at least three key reasons why the ROK is finally becoming interested in the Pacific Islands. First, the expansion of the ROK-U.S. alliance into a “global comprehensive strategic alliance” is creating new missions and responsibilities on the part of the ROK that it is forced to fulfill.14 For example, the Biden administration has clearly encouraged and welcomed the ROK’s outreach to the Pacific Island countries as part of its own 2022 Pacific Partnership Strategy, whose fourth line of effort was to ‘Coordinate with Allies and Partners, Within and Beyond the Region.’15

At the April 2023 ROK-U.S. leaders’ summit in Washington, DC, the joint statement stated that “The two Presidents committed to increase cooperation with Southeast Asia and the Pacific Island Countries to promote resilient health systems, sustainable development, climate resilience and adaptation, energy security, and digital connectivity.”16 This has also included U.S. efforts to focus on the Pacific Islands as a priority for ROK-U.S.-Japan trilateral cooperation. For example, the Trilateral ROK-U.S.-Japan Indo-Pacific Dialogue, which was formed following the Camp David summit, states that “The representatives of the United States, Japan, and the ROK discussed each country’s Indo-Pacific approach and opportunities for cooperation, with an emphasis on partnership with Southeast Asian and Pacific Island countries.”17 Agreeing to these statements, repeatedly, creates bureaucratic incentives and pressures to demonstrate some action.

Second, the ROK’s key strategic partners in the Indo-Pacific have also encouraged closer cooperation on Pacific Islands engagement as a new area of common interest. For example, in 2023 the ROK became the eighth member of the Partners in the Blue Pacific (PBP), an informal consultative and coordination initiative to collectively support PIF countries with humanitarian resources, cyber resilience, ocean and fisheries research vessels, and climate change support.18 Bilaterally, the 2024 ROK-Australia 2+2 Foreign and Defense Ministers’ joint statement made extensive reference to the Pacific Islands19 as did New Zealand Prime Minister Christopher Luxon during his visit to Seoul in September 2024.20 The Pacific Islands are therefore likely to be an ongoing focus of the ROK’s bilateral and minilateral discussions with not only the United States but also key Indo-Pacific strategic partners in the years to come.

Third, the ROK’s own rising power, the extent of which remains fiercely debated, is enabling new diplomatic and funding ambitions that historically simply did not exist. In short, even if the ROK had previously desired to play a more active role in the Pacific Islands, it did not have the means to do so until very recently. Growing capacity has created new constituencies advocating for greater investment in fields or regions previously excluded who also highlight the shared interests or identities as a basis for cooperation. In the past two years, the Yoon administration has also hosted major summits with Africa, on democracy, on cross-regional cooperation with NATO, and summits on cyber security and artificial intelligence. At the Third Summit for Democracy, it pledged major increases in spending on democratic governance totaling $100 million. It also hosted the first ROK-Africa Summit in 2024 with almost 50 African countries where the government promised $14 billion in export financing and a similar doubling of ODA to Africa by 2030.21 President Yoon’s speeches on these occasions has emphasized living up a status befitting the ROK’s growing capacity.

3. Assessing the ROK’s Pacific Islands Strategy Performance

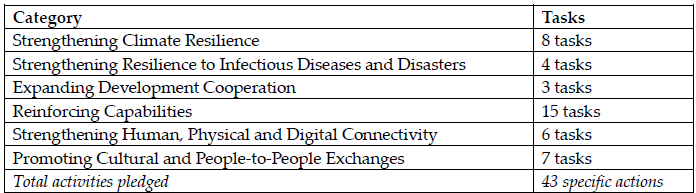

The Yoon administration hosted the 1st Korea-Pacific Leaders’ Summit in Seoul on May 29, 2023, and announced the ‘Declaration and Action Plan on A Partnership in Pursuit of Freedom, Peace and Prosperity for a Resilient Pacific.’22 The Yoon administration called the ROK-PIF summit “a pivotal moment in expanding the ROK’s diplomatic horizon into the Indo-Pacific and bolstering responsible diplomacy through enhanced contributions.”23 The Action Plan is one of the most ambitious roadmaps for cooperation at such a modest starting point, with 43 specific objectives announced in May 2023 (Table 2).24

Table 2. ROK-PIF Action Plan

It appears that at least 10 tasks are being implemented based on the Korea-Pacific Islands Action Plan. In 2024, five ministries introduced approximately 10 new projects under this plan. The Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries led five new initiatives, including the Pacific Islands International Observer Capacity Building Training Program, the Pacific Islands Oceans and Fisheries Education Capacity Building and Master Plan Establishment Program, and the Fiji Makogai Island Marine Research Station Reconstruction and Climate Change Response Capacity Building Project. Additionally, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs launched the Fiji Public Service Digital Transformation Capacity Building Training Program, while the Ministry of the Interior and Safety built the Flood Early Warning System (FEWS) for Fiji.25

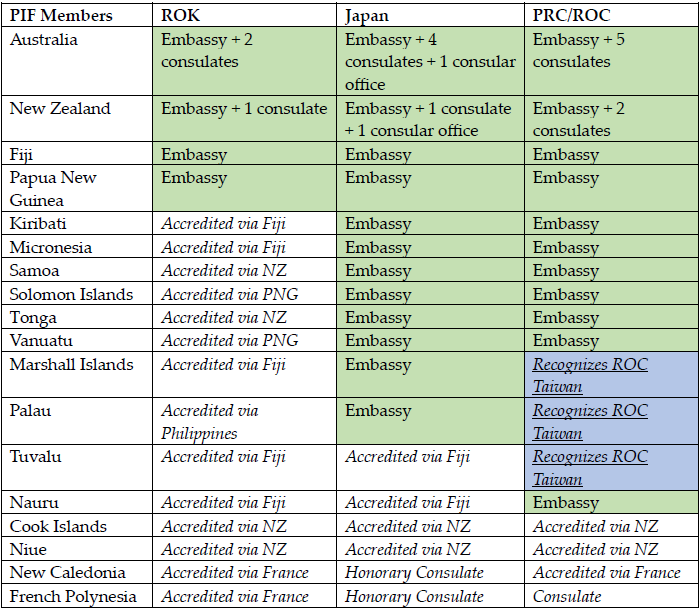

However, other parts of the Action Plan have been slower to be implemented due to resourcing constraints. For example, increasing diplomatic presence was a key priority of the Action Plan. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs established diplomatic relations with Niue in 2023 as part of the ROK-PIF summit.26 Although plans to establish an overseas mission in the Republic of the Marshall Islands had also been mentioned in late 2023, especially given Korea was one of only eight countries to host a diplomatic mission from the Marshall Islands, there had not been progress.27 As shown in Table 3, the ROK has only had four embassies among PIF countries: in Australia, Fiji, New Zealand, and Papua New Guinea. It has relied on accredited representation from its embassies in these countries as well as in France and the Philippines to date. This has been significantly smaller compared to countries like Japan, the People’s Republic of China, and the Republic of China which also has three diplomatic allies in the region. Possible candidates for the ROK to establish embassies in the coming years include Palau, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Samoa, and Tonga.

Table 3. ROK, Japan, PRC, and ROC Diplomatic Representation across PIF

Source: ROK MOFA, Japan MOFA, PRC MFA, and ROC MFA public data and consular statements.

Another area of interest was ROK efforts on development assistance under the Action Plan. For example, the Yoon administration pledged to expand the ROK-PIF Cooperation Fund (RPCF), which was established in 2008 with $300,000 and had only grown to $1.5 million by 2022.28 Following the 2023 ROK-PIF Summit, the Yoon administration reportedly pledged to increase the RPCF by fivefold, to around $7.5 million per annum, bringing it in line with the ASEAN- ROK Cooperation Fund which grew from only $7 million in 2018 to $20 million in 2023.29 The Yoon administration also promised to double ODA funds for the Pacific Islands by 2027 as part of a broader increase in the ROK’s ODA budget by 21%. According to the 2024 ODA implementation plan, the amount of support for the Pacific Islands out of Korea’s total ODA is approximately 33 million dollars.30 This is an increase of $12 million compared to the 2023 ODA support for the Pacific Islands. It is true that the amount of support for the Pacific Islands has increased as promised. However, while the total ODA budget for 2024 increased by 1.49 trillion won (31%) compared to 2023, reaching 6.26 trillion won, the Oceania region’s share rose by 0.1%, a relatively small increase compared to other regions.31

In short, the ROK has made a promising start but sometimes struggled to increase its allocation of diplomatic, personnel, and financial resources to match its ambitions. How, then, could the ROK make best use of its limited resources to expand its contribution to the Pacific Islands and also fulfill the expectations of its key strategic partners? The next section discusses how the ROK might better coordinate its approach with its allies and partners.

4. Synergies with Allies and Partners

The ROK is not engaging the Pacific Islands in isolation.32 Instead, its approach has been developed in close consultation with the United States and strategic partners who are members of the region such as Australia and New Zealand, or who have a longer history of engagement with the region such as Japan and France. This section examines how ROK-Pacific Islands cooperation can leverage and accelerate what key partners are already doing with Pacific Island countries to best make use of the ROK’s limited resources. It focuses on the ROK’s relations with the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan.33

These four countries are part of the Partners in the Blue Pacific (PBP) partnership, a consultative forum that also includes Canada, the United Kingdom, and Germany. Moreover, ROK-Australia-Japan-New Zealand cooperation is increasing as part of their participation in the NATO Indo-Pacific Four (NATO IP4) forum which has brought the leaders of the four countries together on several occasions, including most recently at the NATO Summit in September 2024 in Washington, DC. The analysis suggests that ROK cooperation could be tailored to the priorities and capacities of individual partners in addition to PBP efforts. With the United States, this could focus on Micronesian resilience, with Australia this could focus on maritime security capacity building, with New Zealand this could focus on health and skills training, and with Japan this could focus on development assistance and disaster response.

4.1. United States: ROK-U.S. Focus on Micronesia

For U.S. policymakers, the South Pacific is closely connected to the legacy of the Second World War’s Pacific campaign and the war against Imperial Japan. The U.S. footprint in the Pacific Islands includes the state of Hawaii, three overseas territories of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, and American Samoa; three “freely associated” states of the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, and Palau who have a Compact of Free Association (COFA). All these locations retain geostrategic value today despite major advances in military technology. Similarly, China’s growing influence and territorial ambitions in the South Pacific are often framed as echoing Imperial Japan’s Pacific campaign, such as island chains, footholds, and lines of supply. The Biden administration has taken several steps to restore U.S. influence in the Pacific, including with PIF. In 2022 and 2023 it hosted the first-ever U.S.-PIF leaders’ summits, including pledges of economic assistance of $810 million, new diplomatic relations, cooperation on climate change and illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing, and defense and security capacity-building support.34

At the 2023 ROK-U.S. Summit and the Camp David Accords, the ROK and the United States pledged to cooperate with Pacific Island countries, reaffirming their commitment to contribute through initiatives like the PBP. The United States is pursuing the PBP as a key strategy to strengthen cooperation with Pacific Island countries while making it clear that this initiative will not expand into a security agreement.35 As a PBP partner, the ROK can collaborate on various issues such as climate change, economic development, and infrastructure, in line with its Indo-Pacific Strategy. By linking cooperation with the 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent, Korea, and the U.S. can prioritize areas like climate resilience, development assistance, sustainable development, digital connectivity, and fisheries protection.

• Policy Recommendation 1: The ROK and the United States could narrow their alliance cooperation to focus on Micronesia with U.S. territories and COFA partners as a sub-regional hub for further outreach across the PIF. This is similar to the ROK’s focus on the Greater Mekong Sub-region (GMS) in its Southeast Asia strategy, which has its own dedicated Mekong-ROK Cooperation Fund.36 Similarly, the ROK could establish a ROK-U.S. Micronesia Cooperation Fund with an office in Guam to oversee ROK-U.S. joint projects as well as ensure that ROK funding is coordinated with the U.S. Department of Interior which handles COFA financial assistance and Western Pacific territories.

4.2. Australia: ROK-Australia Focus on Maritime Capacity Building

Australia cooperates with the Pacific Island countries in various areas such as diplomacy, economy, security, and climate change. It is the largest donor of ODA to Pacific Island countries and a major trading partner. In November 2018, Prime Minister Morrison announced the ‘Pacific Step Up’ policy, opening a new chapter in relations and emphasizing a higher level of engagement that has been expanded under the current Albanese government and Foreign Minister Penny Wong and a dedicated Minister for the Pacific. Key initiatives include the signing of security partnerships and treaties, the Pacific Maritime Security Program (PMSP), the Defense Infrastructure Partnership, and the Cyber and Critical Technology Cooperation Program. Australia’s defense and security cooperation with the Pacific Islands is wide-ranging and seeks to advance the comprehensive concept of security as articulated in the 2018 Boe Declaration. It also operates the Pacific Labour Mobility Scheme to provide jobs for Pacific and Timor-Leste workers to develop their skills and support their families back home.37

The 2021 ROK-Australia Comprehensive Strategic Partnership has led to renewed interest in bilateral cooperation with the Pacific Islands, building on earlier interest in the 2015 Blueprint for Defence and Security Cooperation. At the 2+2 meeting in May this year, the two governments also reaffirmed their will to strengthen cooperation by seeking ways to cooperate with Pacific Island countries to contribute to maritime security in the Indo-Pacific region.38 The ROK can enhance maritime security cooperation in the region, leveraging its growing defense ties with Australia. This includes the recent visit by the Australian Border Force Commissioner to the Korea Coast Guard Headquarters in May, signaling increased cooperation. As both countries expand their information-sharing and capacity-building programs, this collaboration should extend to Pacific Island countries. Additionally, Australia is investing in key infrastructure projects through the Blue Dot Network with the U.S. and Japan, where ROK’s technology and resources can support essential developments like submarine cables and port construction for the South Pacific’s economic growth.

• Policy Recommendation 2: The ROK and Australia could prioritize cooperation on maritime coastal patrol capacity building as a flagship effort.39 Australia’s Pacific Maritime Security Program (PMSP) has been a signature capacity-building program for almost 40 years, delivering dozens of patrol boats including the Pacific Forum-class patrol boats, the Guardian-class patrol boats, and now the Cape-class patrol boats to most PIF members. However, as Australian shipbuilders ramp up their construction work for Australia’s own naval requirements,40 there is an opportunity for the ROK’s shipbuilders who already have a longstanding presence in Southeast Asia to help address any shortfalls in new construction or maintenance, repair, and overhaul (MRO) needs as well as to supply advanced uncrewed surface vessels for surveillance of exclusive economic zones.41

4.3. New Zealand: ROK-NZ Focus on Health and Skills Training

New Zealand has strong cultural, economic, and political ties with Pacific Island nations, especially in Polynesia, where it has ‘free association’ sovereignty-sharing arrangements with the Cook Islands, Tokelau, and Niue. The Pacific is a key part of New Zealand’s national strategy, with Pacific resilience and security highlighted in its first-ever National Security Strategy 2023-2028, titled ‘Secure Together.’42 In 2018, New Zealand launched the Pacific Reset, moving away from donor-recipient relationships and shifting toward partnerships to address shared challenges. New Zealand emphasizes development cooperation in the Pacific, reflecting its historical and ethnic ties. In 2023, over 60% of its NZD$ 746.4 million ODA went to Pacific Island countries, focusing on areas like renewable energy, fisheries, economic resilience, and health.43 The 2023 OECD-DAC Peer Review praised New Zealand’s partner-led approach, emphasis on indigenous values, funding of civil society, and increased climate finance commitments.44 Most recently, New Zealand’s new Prime Minister Christopher Luxon visited Seoul on an official visit where the two leaders emphasized cooperation via the PBP and also on Antarctica.45

While the ROK and New Zealand recognize their partnership in the Indo-Pacific, there has been limited discussion on specific cooperation areas, making the Pacific Islands a potential priority for collaboration. New Zealand’s extensive network with over 30 Pacific Island government agencies and its ‘Four-year Development Plan’ with 14 Pacific nations could guide the ROK in expanding partnerships. Additionally, Japan and New Zealand’s joint projects, like the Betio Hospital in Kiribati, illustrate successful collaboration in the region.46 As geopolitical dynamics evolve, New Zealand is strengthening its influence, with Prime Minister Luxon pledging to increase engagement across the Indo-Pacific and emphasizing collaboration with countries like Australia, the UK, Japan, ASEAN, and India.47

• Policy Recommendation 3: The ROK and New Zealand could focus on high-value cooperation that does not rely on large budgets or personnel-heavy deployments across the Pacific Islands, including health technology support such as telemedicine and modular medical equipment production. New Zealand’s Polynesia Health Corridors program, which strengthens links between Polynesian health sectors, is a relevant model. Another area of interest could be education and skills training via ROK institutions partnering with New Zealand training institutions. For example, the ROK’s world-leading science, technology, engineering, and medicine (STEM) faculties have strong research partnerships with New Zealand and there is a particular focus on Antarctic and environmental research. Funding to establish joint fellowships for Pasifika postgraduates to study in Korea, like the highly successful KDI programs, could be co-managed to bring ROK experts to programs in New Zealand.

4.4. Japan: ROK-Japan Focus on Development Assistance and Disaster Response

Since the 1960s, Japan has developed relations with the Pacific Islands through fisheries and development cooperation. The Pacific Islands Leaders Meeting (PALM), held every three years since 1997, is a key forum for regional issues. Japan’s Indo-Pacific Strategy, rooted in Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s 2016 “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” vision, has evolved as the discourse on the Indo-Pacific region has broadened.48 In 2021, Prime Minister Suga introduced the Pacific Bond (KIZUNA) policy to strengthen ties between Japan and Pacific Island countries49 and in 2023, Prime Minister Kishida announced a New Plan for a Free and Open Indo-Pacific, emphasizing connectivity in the Pacific Islands region.50Japan’s cooperation with the Pacific region now includes security and military aspects. At the 10th Pacific Island Leaders’ Meeting (PALM10) in July, Japan announced the “Japan-Pacific Islands Joint Action Plan,” highlighting increased involvement of the Self-Defense Forces, including defense exchanges, port visits, and disaster relief. In December 2023, Japan signed an Official Security Assistance (OSA) agreement with Fiji to provide patrol boats and related equipment, strengthening security ties with the Pacific region.51

Since President Yoon took office, the ROK has made steady progress in improving bilateral relations with Japan, establishing a foundation for cooperation. The Camp David Accords highlighted ASEAN and the Pacific Islands as key areas for collaboration among Korea, the United States, and Japan. The 2023 Joint Statement from the ROK-U.S.-Japan Deputy Foreign Ministers reaffirmed the importance of effective cooperation with the Pacific Islands in line with the “2050 Strategy for a Blue Pacific Continent.”52 This commitment was echoed in the January 2024 Trilateral Indo-Pacific Dialogue, which emphasized the significance of collaboration in the Pacific region. Both countries are actively translating their willingness to cooperate into action.

The October 2023 Japan-ROK-U.S. Joint Statement from the inaugural Development and Humanitarian Assistance Policy Dialogue outlined plans to strengthen collaboration among ODA agencies like Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA), United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and to identify specific development projects. Potential areas for cooperation include climate change response, connectivity, maritime security, cyber security, and artificial intelligence. Furthermore, the 2024 Comprehensive Implementation Plan for Korea’s international development cooperation promotes “strategic green ODA,” focusing on renewable energy and hydrogen economy projects.53Japan’s PALM10 Joint Action Plan also emphasizes clean energy initiatives. Both the ROK and Japan possess the resources and technology for such support, and cooperation is expected, especially following their agreement in April 2024 to enhance collaboration in decarbonizing new energy.54

• Policy Recommendation 4: The ROK and Japan should explore how to de-conflict their respective development assistance programs in the Pacific Islands, identify areas for bilateral coordination or cooperation, and explore opportunities for trilateral and minilateral humanitarian assistance cooperation with the United States. For example, Japan’s JICA recently announced a $70 million standby loan to Fiji that can be activated in the event of a natural disaster such as a cyclone.55 This is a valuable tool that can save time and bureaucratic efforts in the chaotic days and weeks following a disaster. The ROK’s KOICA small office in Fiji could explore ways to coordinate a mutual fund for PIF countries that also attracts public and private funding. This would produce a more substantial financial loan than what KOICA can allocate by itself.

Conclusion

The United States, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan have all taken significant steps to strengthen their relationships with Pacific Island countries. Each country has its own distinct priorities, niche capabilities, strengths and limitations when it comes to cooperating with the Pacific Island countries to contribute to the region’s security and prosperity. While the ROK may not yet match these countries in terms of the depth and scale of cooperation, by learning from their strategies and cooperating with these countries, the ROK can develop a flexible and effective approach. With the groundwork already set through summits and reports, South Korea must now focus on moving from planning to concrete actions, strategically applying its resources to enhance its engagement with the Pacific Islands.

The ROK’s ambitious Pacific Islands strategy is still a work in progress. It will feature uniquely Korean technical assistance to the needs of the region, expanding diplomatic relationships, and modest but targeted resource contributions. It will also be shaped by multilateral coordination through forums such as the Partners in the Blue Pacific initiative to harmonize and aggregate the efforts of many extra-regional countries. This is to ensure that Pacific Island countries will always have choices and options when it comes to their own development and security needs. In between these two approaches will be the tailored bilateral and minilateral partnerships outlined in this Issue Brief, elevating the ROK-U.S. alliance and the ROK’s key strategic partnerships to work together as a force for good in the Blue Pacific Continent.

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 1. Stephen Dziedzic, “Despite Beijing’s attempts to ‘lure’ more support in the Pacific, Taiwan’s top diplomat in Australia backs ties with Tuvalu,” ABC News (February 5, 2024), https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-02-05/taiwan-tuvalu-beijing-china-pacific-diplomatic-switch-ties-/103421410; Meg Keen and Mihai Sora, “Nauru’s diplomatic switch to China – the rising stakes in Pacific geopolitics,” The Interpreter, Lowy Institute (January 18, 2024), https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/nauru-s-diplomatic-switch-china-rising-stakes-pacific-geopolitics.

- 2. Prianka Srinivasan and Virginia Harrison, “Mapped: the vast network of security deals spanning the Pacific, and what it means,” The Guardian (July 9, 2024), https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/jul/09/pacific-islands-security-deals-australia-usa-china; Kirsty Needham, “China seeks Pacific islands policing, security cooperation -document,” Reuters (May 26, 2022), https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/exclusive-china-seeks-pacific-islands-policing-security-cooperation-document-2022-05-25/; Christian Shepherd, “China fails on Pacific pact, but still seeks to boost regional influence,” The Washington Post (June 1, 2022), https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/06/01/china-influence-pacific-deal-wang/.

- 3. For the most comprehensive assessment of ROK-Pacific Islands cooperation, see Ina Choi, Geeyoung Oh, Youngsun Kim, Soeun Kim, and Hanbyeol Jang, Korea’s Indo-Pacific Bridge: Charting a Course for ROK-Pacific Islands Partnership, Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, Policy Analyses 23-33 (December 29, 2023); 최인아, 오지영, 김영선, 김소은, 장한별, “인도-태평양 전략 추진을 위한 한-태평양 도서 국중 장기 협력 방안,” 대외경제정책연구원·(2023년 12월 29일)

https://www.kiep.go.kr/gallery.es?mid=a10101010000&bid=0001&list_no=11395&act=view. - 4. Pacific Islands Forum, “Report: Declaration and Action Plan of the 1st Korea-Pacific Leaders’ Summit, 2023″ (May 29, 2023), https://forumsec.org/publications/report-declaration-and-action-plan-1st-korea-pacific-leaders-summit-2023.

- 5. Youngyoon Amy Seo, “The Impact of Korean Communities in Guam,” Guampedia, https://www.guampedia.com/the-impact-of-korean-communities-in-guam/.

- 6. Charlotte Greenfield, “Pacific nations crack down on N.Korean ships as Fiji probes more than 20 vessels,” Reuters (September 15, 2017), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-northkorea-missiles-pacific-shipping/pacific-nations-crack-down-on-north-korean-ships-as-fiji-probes-more-than-20-vessels-idUSKCN1BQ0ZQ/.

- 7. Island Times Staff, “Hitting where it hurts: Pacific waters off-limits to North Korean vessels,” Island Times (October 6, 2017), https://islandtimes.org/hitting-where-it-hurts-pacific-waters-off-limits-to-north-korean-vessels/.

- 8. Pitcairn Island, which is administered by the United Kingdom, and Easter Island, which is administrated by Chile, are two notable omissions from the PIF.

- 9. Pacific Islands Forum, “Partnerships,” https://forumsec.org/partnerships.

- 10. Grant Wyeth, “Guam, American Samoa Upgraded to Associate Membership in Pacific Islands Forum,” The Diplomat (August 30, 2024), https://thediplomat.com/2024/08/guam-american-samoa-upgraded-to-associate-membership-in-pacific-islands-forum/; Marianas Business Journal Staff, “Guam, American Samoa PIF status upgraded to associate membership,” Marianas Business Journal (August 30, 2024), https://www.mbjguam.com/guam-american-samoa-pif-status-upgraded-associate-membership.

- 11. Joanne Wallis and Jiye Kim, “Why did South Korea invite Pacific leaders to a summit, and why did they go?”, The Strategist (May 31, 2023), https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/why-did-south-korea-invite-pacific-leaders-to-a-summit-and-why-did-they-go/; Philip Turner, “Pacific promise: South Korea charts an ambitious course in an emerging region,” Korea Pro (June 30, 2023), https://koreapro.org/2023/06/pacific-promise-south-korea-charts-an-ambitious-course-in-an-emerging-region/; Troy Stangarone, “South Korea’s Deepening Ties With Pacific Island States,” The Diplomat (September 26, 2023), https://thediplomat.com/2023/09/south-koreas-deepening-ties-with-pacific-island-states/.

- 12. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Australian Government, “Republic of Korea country brief,” https://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/republic-of-korea/republic-of-korea-country-brief.

- 13. New Zealand Trade and Enterprise, “New Zealand businesses to bolster Asia trade ties on PM Mission” (August 27, 2024), https://www.nzte.govt.nz/blog/new-zealand-businesses-to-bolster-asia-trade-ties-on-pm-mission.

- 14. The White House, “United States-Republic of Korea Leaders’ Joint Statement” (May 21, 2022), https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/05/21/united-states-republic-of-korea-leaders-joint-statement/.

- 15. The White House, “Pacific Partnership Strategy of the United States” (September 2022), p. 7 and 9, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Pacific-Partnership-Strategy.pdf.

- 16. The White House, “Leaders’ Joint Statement in Commemoration of the 70th Anniversary of the Alliance between the United States of America and the Republic of Korea” (April 26, 2023), https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/04/26/leaders-joint-statement-in-commemoration-of-the-70th-anniversary-of-the-alliance-between-the-united-states-of-america-and-the-republic-of-korea/.

- 17. U.S. Department of State, “Joint Statement on the Trilateral United States-Japan-Republic of Korea Indo-Pacific Dialogue” (January 6, 2024), https://www.state.gov/joint-statement-on-the-trilateral-united-states-japan-republic-of-korea-indo-pacific-dialogue/.

- 18. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Australian Government, “Joint Statement on Partners in the Blue Pacific Foreign Ministers Meeting” (September 22, 2023), https://www.dfat.gov.au/news/media-release/joint-statement-partners-blue-pacific-foreign-ministers-meeting-0.

- 19. Department of Defence, Australian Government, “Australia-Republic of Korea 2+2 Joint Statement” (May 1, 2024), https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/statements/2024-05-01/australia-republic-korea-22-joint-statement.

- 20. New Zealand Government, “Joint Statement between the Republic of Korea and New Zealand 4 September 2024, Seoul” (September 4, 2024), https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/joint-statement-between-republic-korea-and-new-zealand-4-september-2024-seoul.

- 21. Song Kyung-jin, “Inaugural Korea-Africa Summit: A sustainable path for shared prosperity,” The Korea Times (May 21, 2024), https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/opinion/2024/10/638_375011.html.

- 22. Pacific Islands Forum, “Report: Declaration and Action Plan of the 1st Korea-Pacific Leaders’ Summit, 2023” (May 29, 2023), https://forumsec.org/publications/report-declaration-and-action-plan-1st-korea-pacific-leaders-summit-2023.

- 23. The Government of the Republic of Korea, “2023 Progress Report of the ROK’s Indo-Pacific Strategy” (December 2023), p. 6.

- 24. Office of the President, Republic of Korea, “Action Plan for Freedom, Peace and Prosperity in the Pacific 2023 Korea-Pacific Islands Summit” (May 29, 2023), https://eng.president.go.kr/briefing/PPZpzzTA.

- 25. Fiji Government, “New Flood Early Warning Systems Boost Fiji’s Disaster Preparedness Amid Growing Climate Risks” (September 25, 2024), https://www.fiji.gov.fj/Media-Centre/News/NEW-FLOOD-EARLY-WARNING-SYSTEMS-BOOST-FIJI-S-DISAS.

- 26. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Korea, “Korea, Pacific Island Niue forge formal ties”

(May 29, 2023), https://www.korea.net/NewsFocus/Korea_in_photos/view?articleId=233369. - 27. Kim Seung-yeon, “S. Korea to establish new diplomatic missions in 12 countries next year,” Yonhap News (November 7, 2023) https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20231107007600315.

- 28. Pacific Islands Forum, “Remarks: Deputy Foreign Minister of the Republic of Korea at Korea-Pacific Islands Countries Seminar” (June 25, 2022), https://forumsec.org/publications/remarks-deputy-foreign-minister-republic-korea-korea-pacific-islands-countries-seminar.

- 29. Fiji Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Korean President Conveys Message of Support to the Hon. Prime Minister” (October 13, 2023), https://www.foreignaffairs.gov.fj/korean-president-conveys-message-of-support-to-the-hon-prime-minister/; See also “ASEAN – Korea Cooperation Fund (AKCF) Annual Report 2023”(August 26, 2024), https://www.aseanrokfund.com/resources/asean-korea-cooperation-fund-akcf-annual-report-2023.

- 30. ODA Korea, “2024 Comprehensive Implementation Plan for International Development Cooperation [In Korean]” 48th International Development Cooperation Committee (February 29, 2024), p. 10.

- 31. The share of total ODA support for Oceania rose from 0.7% in 2023 to 0.8% in 2024. Other regions that saw an increase in ODA share include the Middle East/CIS (from 4.1% to 9.2%), Central and South America (from 7.5% to 7.7%), and other areas (from 29.8% to 32.2%).

- 32. Lee Jaehyon and Kim Minjoo, “Same, but different, foreign policies and regional strategies of Australia and New Zealand: Implication for Korea’s foreign policy,” Asan Issue Brief (January 8, 2024), https://en.asaninst.org/contents/same-but-different-foreign-policies-and-regional-strategies-of-australia-and-new-zealand-implication-for-koreas-foreign-policy/.

- 33. The analysis could further be expanded to cover European countries such as France and the United Kingdom which continue to have colonial territories in the South Pacific as well as Southeast Asian countries such as Indonesia and Singapore which are also increasing their engagement.

- 34. The White House, “FACT SHEET: Enhancing the U.S.-Pacific Islands Partnership” (September 25, 2023), https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/09/25/fact-sheet-enhancing-the-u-s-pacific-islands-partnership/.

- 35. U.S. Department of State, “Readout of the Partners in the Blue Pacific (PBP) Ministerial” (September 22, 2023), https://www.state.gov/briefings-foreign-press-centers/readout-of-pbp-ministerial.

- 36. Mission of the Republic of Korea to ASEAN, ” ROK & ASEAN,” https://overseas.mofa.go.kr/asean-en/wpge/m_2561/contents.do.

- 37. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Australian Government, “Shared security in the Pacific” https://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/pacific/shared-security-in-the-pacific.

- 38. Republic of Korea Policy Briefing, “The 6th Korea-Australia Foreign Affairs and Defense (2+2) Ministerial Meeting Held [In Korean]” (May 1, 2024), https://www2.korea.kr/briefing/pressReleaseView.do?newsId=156628546&pWise=sub&pWiseSub=C10.

- 39. For a more extensive discussion of this option, see Peter K. Lee (ed.), Ristian Atriandi Supriyanto, Renato Cruz De Castro, Collin Koh, and Lan-Anh Nguyen, “Many hands: Australia-US contributions to Southeast Asian maritime security resilience,” United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney (November 2022).

- 40. Andrew Greene, “Defence engineers flying to Pacific to repair defective Australian-built Guardian-class patrol boats,” ABC News (June 30, 2022), https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-07-01/guardian-class-patrol-boat-issues/101197634.

- 41. Lee Minji, “S. Korea tests unmanned surface vehicle operation against N. Korean threats,” Yonhap News Agency (October 10, 2024), https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20241010005200315.

- 42. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, “New Zealand’s National Security Strategy: Secure Together Tō Tātou Korowai Manaaki” (October 3, 2024), https://www.dpmc.govt.nz/our-programmes/national-security/new-zealands-national-security-strategy.

- 43. New Zealand Foreign Affairs and Trade, “Our development cooperation partnerships in the Pacific,” https://www.mfat.govt.nz/en/aid-and-development/our-development-cooperation-partnerships-in-the-pacific; see also, “New Zealand’s development assistance,” https://www.mfat.govt.nz/en/aid-and-development/our-approach-to-aid/where-our-funding-goes.

- 44. OECD iLibrary, “Development Co-operation Profiles: New Zealand,” https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/138471d6-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/5e331623-en&_csp_=b14d4f60505d057b456dd1730d8fcea3&itemIGO=oecd&itemContentType=chapter.

- 45. Office of the President, Republic of Korea, “Joint Statement between the Republic of Korea and New Zealand” (September 4, 2024), https://eng.president.go.kr/briefing/QEqy97DW.

- 46. New Zealand Government, “Pacific Futures” (July 19, 2024),https://www.beehive.govt.nz/speech/pacific-futures.

- 47. New Zealand Government, “Foreign Policy Speech to the Lowy Institute” (August 15, 2024), https://www.beehive.govt.nz/speech/foreign-policy-speech-lowy-institute.

- 48. Tomotaka Shoji, “ASEAN’s Ambivalence toward the Vision of a ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’ Mixture of Anxiety and Expectation,” Sasakawa Peace Foundation (September 18, 2018), https://www.spf.org/iina/en/articles/shoji-southeastasia-foips.html.

- 49. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “The Ninth Pacific Islands Leaders Meeting (PALM9) (Overview of Results)” (July 2, 2021), https://www.mofa.go.jp/a_o/ocn/page3e_001123.html.

- 50. Pacific Islands Forum, “Declaration: The 10th Pacific Islands Leaders Meeting (PALM10) Japan – Pacific Islands Forum Leaders’ Declaration” (July 18, 2024), https://forumsec.org/publications/declaration-10th-pacific-islands-leaders-meeting-palm10-japan-pacific-islands-forum.

- 51. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “Signing and Exchange of Notes for Official Security Assistance (OSA) to the Republic of Fiji” (December 18, 2023), https://www.mofa.go.jp/press/release/pressite_000001_00060.html.

- 52. U.S. Department of State, “Joint Statement on the U.S.-Japan-Republic of Korea Trilateral Ministerial Meeting” (February 13, 2023), https://www.state.gov/joint-statement-on-the-u-s-japan-republic-of-korea-trilateral-ministerial-meeting-2/.

- 53. ODA Korea, “2024 Comprehensive Implementation Plan for International Development Cooperation [In Korean],” 48th International Development Cooperation Committee (February 29, 2024), p. 23.

- 54. Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, Republic of Korea, “Korea and Japan hold 1st Hydrogen Cooperation Dialogue meeting,” (June 14, 2024), https://www.korea.net/Government/Briefing-Room/Press-Releases/view?articleId=7441&type=O.

- 55. Monishka Pratap, ”Fiji signs $75M standby loan with JICA for disaster recovery preparedness,” Fijivillage (November 10, 2024), https://www.fijivillage.com/news/Fiji-signs-70M-standby-loan-with-JICA-for-disaster-recovery-preparedness-xf4r85/.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter