Introduction1

2017 is shaping up to be a critical year for the Republic of Korea (hereafter, Korea or ROK). Domestically, Koreans await the outcome of President Park Geun-hye’s impeachment which, if approved by the Constitutional Court, will force an early presidential election in the coming months. Relations with Korea’s largest trading partner, China, have deteriorated as China intensifies its boycott of Korean cultural exports and consumer products over plans to deploy THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defense) on the Korean Peninsula. The Chinese reaction to THAAD has resulted in an intense debate within Korea on how to balance its military alliance with the U.S. and its economic relationship with China. Moreover, the election of U.S. President Donald Trump has begun to transform America’s relationships with China and Russia and alter the geopolitical and economic landscape throughout Northeast Asia.

Using the Asan Institute for Policy Studies’ regular public opinion surveys and special surveys, this issue brief will examine how Koreans assess the rivalry between the United States and China, the changing geopolitical and economic dynamics in Northeast Asia, and THAAD.

This issue brief makes the following conclusions. First, Koreans still value their country’s cooperation with the United States more than with China. An increasing number of Koreans see the U.S. as having greater economic and political influence on world affairs. We believe that this is the result of deteriorating ROK-China relations, coupled with China’s declining favorability among Koreans. At the same time, however, Koreans’ support of THAAD has dropped precipitously. This change is likely the result of a growing dissatisfaction with the Park administration, rather than a concern over potential fallout with China. Therefore, both current and future Korean governments must improve their communication with the public regarding sensitive issues, including THAAD, and regain the public’s trust and support.

Korea In Between the U.S. and China

A major concern emanating from Trump’s presidential victory is a significant shift in great power relations in Northeast Asia. Throughout the campaign, Trump exhibited pro-Russia tendencies, evident in the way he addressed the Russian hacking accusations, hinted at the possibility of lifting sanctions against Russia, and openly expressed friendliness towards Russian President Vladimir Putin. On the other hand, his open hostility towards China was best exemplified by his phone call with Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen and his statement that “Everything is under negotiation including One China.”2 Given that Trump’s interactions with China will have far-reaching consequences for Korea, many Koreans have been paying close attention to these developments. Korea finds itself in a precarious situation because the United States remains its most important security ally while China remains its most important trading partner. If the US-China relationship hits a rough patch, Korea will be faced with the difficult task of balancing these most vital of relationships.

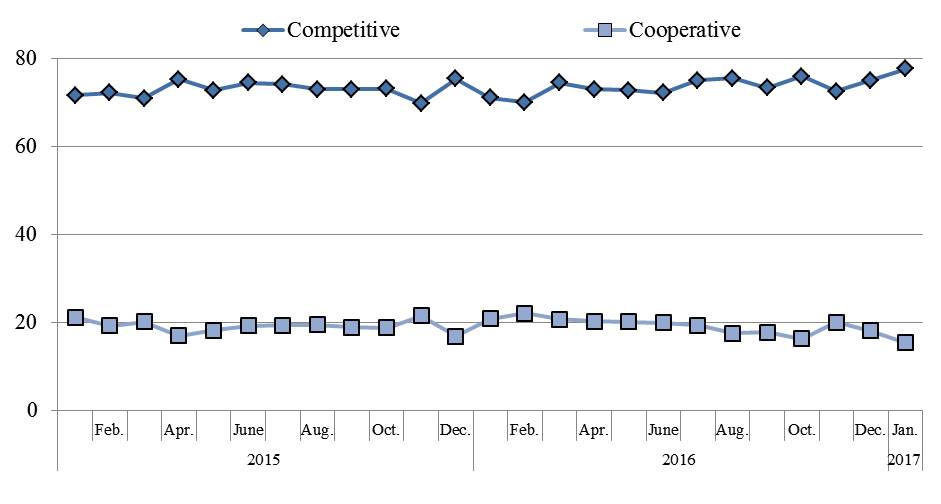

Many Koreans are aware of the changing dynamics in Northeast Asia. Specifically, more Koreans described US-China relations as being competitive rather than cooperative in the most recent survey. According to the Asan Institute’s surveys since 2015, about 69.8% to 75.0% of Koreans believed as such. The number peaked at 77.6% in January 2017. This is likely due to the escalating conflicts in the South China Sea and trade-related issues between the two countries that were exacerbated upon Trump’s election. In contrast, only 15.4% of Koreans in January 2017 saw the relationship as being cooperative, the lowest since 2015. Koreans also projected that conflicts between the two countries in Northeast Asia would spill over and develop into a superpower rivalry.

Figure 1. Korean Perception about US-China Rivalry(%)3

Race for Political and Economic Superiority: U.S. vs. China

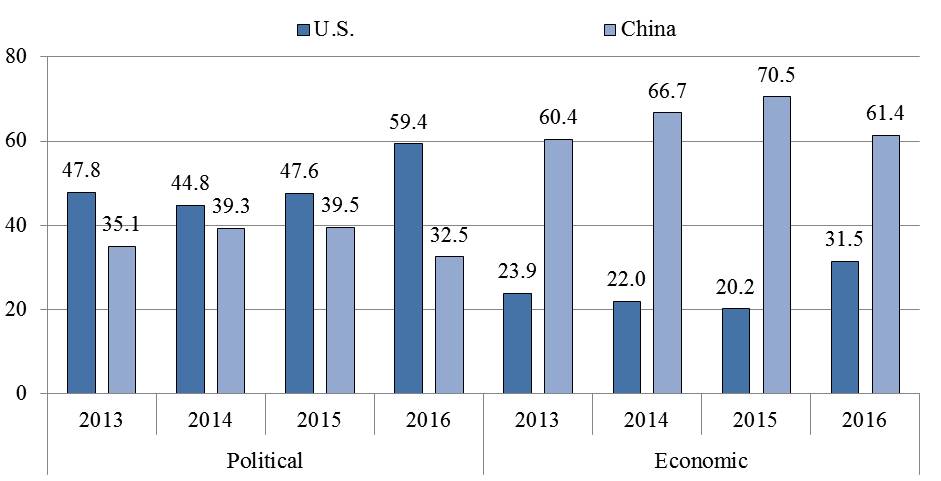

Although China’s recent economic slowdown has decelerated its rise, it still continues to challenge America’s hegemonic status. We asked Koreans how they view the rivalry between the two countries. Specifically, we asked them which of the two superpowers will possess greater economic and political influence in world affairs in the future. We compared the November 2016 survey with those conducted since 2013.

In 2016, the number of Koreans who projected America’s economic and political dominance increased. In terms of future political influence, 59.4% of respondents said that the U.S. will maintain its superiority over China. This number is the highest since 2013, when less than half (47.8%) projected as such. In 2014 and 2015, 44.8% and 39.5% of respondents agreed, respectively. On the other hand, the percentage of Koreans who believed that China will be the main political influencer dropped to its lowest point, 32.5%, in 2016. Prior to this, the numbers were 35.1% in 2013, 39.3% in 2014, and 39.5% in 2015.

In terms of economic influence, a majority of Koreans (61.4%) still assessed that China will be the dominant economic force in the future. This number, however, was a significant break from the previous trend. In 2013, 60.4% of respondents picked China as the greater economic power, and the numbers increased in subsequent years (66.7% in 2014 and 70.5% in 2015) before falling by almost 10% this year. On the other hand, 23.9% in 2013, 22% in 2014, and 20.2% in 2015 picked the U.S. as the greater future economic power. In 2016, this number rose by almost 10% to 31.5%. Overall, 2016 was a year in which the Korean public saw the U.S. winning both the economic and political battles against China.

Figure 2. Assessing Future Political & Economic Superpower (%)4

A number of factors appeared to have contributed to this recent trend. First is the slowdown in China’s economic growth to around 6%, coupled with projections of a U.S. economic recovery, as exemplified by their lowest unemployment rate in nine years (4.6% in December 2016). Second is the impact of the Trump presidency and his tough trade talks against China. In particular, his retaliatory trade policies and promise to name China as a “currency manipulator” appeared to have convinced many Koreans that the U.S. remains ahead in the rivalry. Trump’s anti-China rhetoric, a defensive mechanism to counter a rising China, has reinforced American superiority in the minds of Koreans. Lastly, Koreans’ view of China as a global leader has changed as ROK-China relations have cooled and China’s favorability among Koreans has dropped.

Korea’s Choice

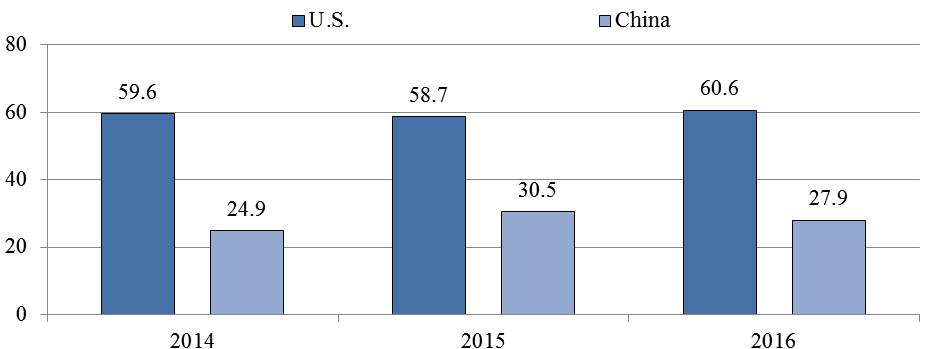

As a country that depends heavily on the U.S. and China, Korea is faced with a difficult situation, especially if US-China relations worsen. We asked Koreans to choose which of the two countries was their preferred future partner for Korea. Specifically, we asked respondents which country Korea should strengthen cooperation with, and we compared the results with our previous surveys. The numbers reveal that Korea’s preference has barely fluctuated since 2014. As Figure 3 shows, around 60% of Koreans chose the U.S. over China as their preferred partner. Numbers supporting China also remained relatively consistent. In 2015, when ROK-China relations were at their peak, there was a 5% increase from the previous year, although it dropped slightly to 27.9% in 2016. The changes for both the U.S. and China over the past few years have proven minor, and the majority of Koreans chose the U.S. over China as Korea’s preferred partner.

Figure 3. Korea’s Partner: U.S. vs. China (%)5

When we looked at the results by age cohort, we observed an important development. That development is the pro-Americanization of the Korean youth. 70.4% of Koreans in their 20s chose the U.S. over China, which was greater than the 63.6% chosen by Koreans aged 60 and older, who are known for their pro-American views. The high favorability of the U.S. among Koreans in their 20s appeared to have influenced their choice for Korea’s future partner. While all the age cohorts chose the U.S. over China, the smallest disparity between the numbers was for Koreans in their 40s, who are often more progressive and pro-China. 49.8% of them picked the U.S. while 38.9% of them sided with China. In addition to age cohort, there was a significant disparity between conservatives and progressives. 49.9% of progressives chose the United States while 36.5% chose China. On the other hand, 69.8% of conservatives picked the U.S. while only 21.4% picked China. Overall, however, the preference of the U.S. over China as Korea’s future partner was widespread, regardless of age or ideology.

Table 1. Korea’s Partner: U.S. vs. China, by Age and Ideology (%)6

Public Opinion on THAAD

One prominent issue that has divided the U.S. and China and has had a profound impact on Korea has been the deployment of THAAD on the Korean Peninsula. The United States has been pressing to deploy the missile defense system, an important tool for the ROK-US military’s defense against North Korea’s nuclear threat. China, on the other hand, has voiced strong opposition to THAAD and began boycotting Korea’s cultural exports and consumer products as a symbol of its opposition. THAAD has become an important issue within the US-China superpower rivalry. As a result, Korea has been put in a precarious situation without a clear diplomatic answer.

The need for Korea to adopt THAAD was broached in June 2014 by General Curtis Scaparotti, then commander of USFK. Ever since, THAAD has been at the center of deteriorating ROK-China relations and a topic that has divided Koreans along ideological lines. The Asan Institute began conducting a series of five public opinion surveys on THAAD around the time the Korean government announced its decision to deploy the missile defense system.

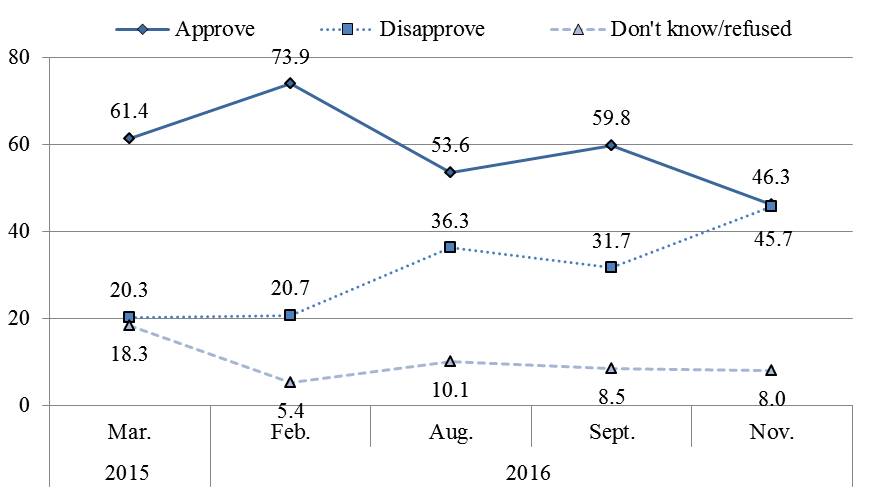

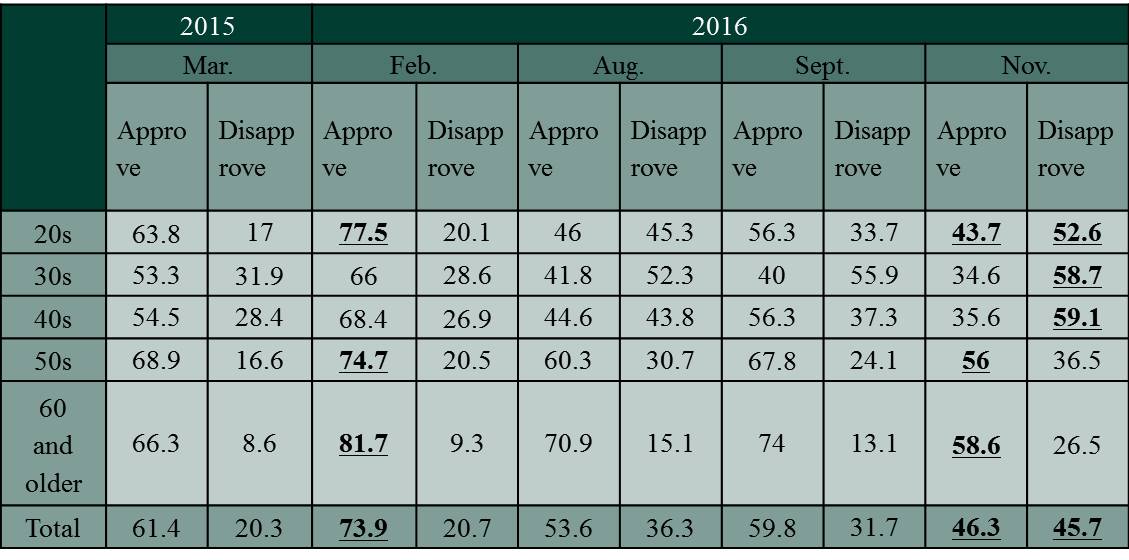

In March 2015, when THAAD was just beginning to become a part of public discourse, the approval and disapproval rates were 61.4% and 20.3%, respectively, while approximately 18% refused to answer or answered that they did not know. Public opinion on THAAD was in its early stages until North Korea conducted its fourth nuclear test in January 2016 and continued its long-range missile tests. In the month after the nuclear test, 73.9% of Koreans approved THAAD, a 13% increase from the previous survey. Those who opposed THAAD remained at 20.7%, indicating that those who answered “don’t know” or refused to answer in the previous survey became convinced that THAAD was a necessity.

The controversy around THAAD picked up steam in July 2016 when the Korean government announced its decision to deploy the missile defense system. Despite the intense public discussion on the issue, the Park administration moved quickly to select the site that would host the THAAD batteries. However, the lack of transparency in the decision-making process by the Park administration turned THAAD into a major domestic political issue. Immediately after the government announcement, the approval rate for THAAD dropped to 53.6% while the disapproval rate surged to 36.3%. The number of respondents who answered “don’t know” or refused to answer returned to double digits (10.1%).7 Furthermore, THAAD quickly became the most controversial topic in Korea when Seongju, North Gyeongsang Province, was announced as the location. Opposition parties, various civil groups, and residents of Seongju strongly opposed the decision. Prime Minsiter Hwang Kyo-ahn and Defense Minister Han Min-koo tried to manage the situation by visiting the area, but ended up adding fuel to the fire.

In the subsequent public opinion surveys conducted after August, public approval rate for THAAD dropped precipitously, while the disapproval rate surged. In August, only 53.6% of respondents approved of THAAD. This was more than a 20% drop from the February survey. 36.3% of respondents disapproved of THAAD (February: 20.7%). In September, the approval rate increased slightly to 59.8% while the disapproval rate was 31.7%.8 During the two months following the announcement of the location for THAAD, both the approval (54%-60%) and disapproval (31%-36%) rates remained relatively unchanged.

A number of factors have influenced how the public views the THAAD issue. Among them are the election of Trump, uncertainties regarding the state of affairs in Northeast Asia, and plummeting public trust in the Park administration. In the November survey, the approval and disapproval ratings for THAAD reached 46.3% and 45.7%, respectively, and were narrowed to within the margin of error. Debates now revolve around postponing the THAAD decision until the next administration, something unthinkable earlier in the year when there was widespread support.

Figure 4. Public Opinion on THAAD (%)9

The age group whose opinion about THAAD changed the most belonged to respondents in their 20s. Back in February, when support for THAAD was at its peak, 77.5% of Koreans in this age group supported the deployment. While there was greater support among Koreans aged 60 and older (81.7%), young Koreans nonetheless showed a strong sense of conservatism on security issues such as THAAD. This number, however, dropped sharply by 33% to 43.7% in November. The strongest resistance to THAAD came from Koreans in their 30s and 40s, who are typically most progressive on security issues. A relatively small percentage of them supported THAAD in February 2016 and almost 60% of them disapproved nine months later. Support among respondents in their 50s also dropped, although not as much as the 20s, 30s, and 40s, whose disapproval rates were around 27-37% in November.

Table 2. Public Opinion on THAAD, by Age (%)10

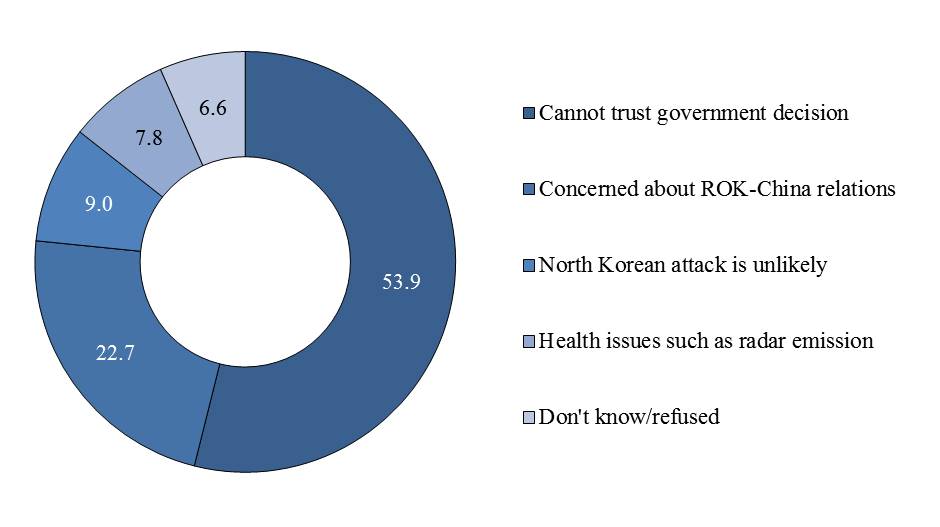

Why did Koreans in their 20s, who have proven to be conservative on security issues, change their minds about THAAD so quickly and so drastically? One factor stands out above the rest: the scandal surrounding President Park and the impact this has had on the public’s trust of the government. When we asked Koreans why they opposed THAAD (n=457), more than half of the respondents (53.9%) answered that they could not trust any decision made by the current government. Only 22.7% answered that they opposed THAAD because of the concern that it might negatively influence ROK-China relations.

62.5% and 70.3% of Koreans in their 20s and 30s, respectively, stated that their distrust of the government was the reason behind their opposition to THAAD. Only 13.5% and 14.2% of Koreans in their 20s and 30s, respectively, opposed THAAD out of fear that ROK-China relations may worsen. Among the age cohorts, Koreans aged 50 and older showed the most amount of concern regarding their country’s relationship with China (50s: 39%; 60 and older: 35.2%).

These results suggest that Korea’s domestic political crisis, not Korea’s relationship with China, is responsible for the weakening public support for THAAD. They are also substantiated by the fact that China’s favorability among Koreans does not influence Korean public opinion on THAAD. For instance, when we compared China’s favorability ratings between those who support and oppose THAAD, the results were statistically insignificant at 4.86 and 4.9111, respectively. Therefore, Korea’s public opinion on THAAD is not influenced by how much Koreans like or dislike China. Rather, it is determined by domestic factors.

Figure 5. Reasons for Opposing THAAD (%)12

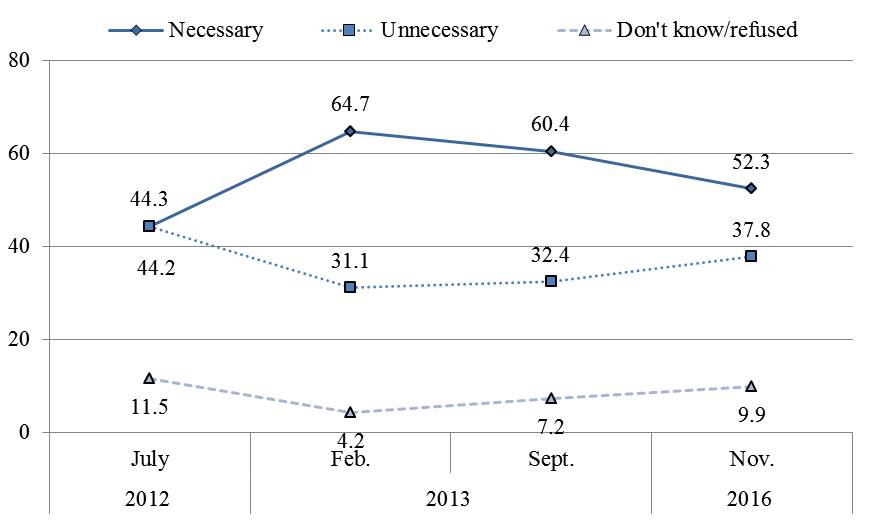

THAAD is a case where domestic factors such as a deteriorating political climate and lack of public trust in the president and the government have influenced Korea’s foreign policy. Koreans have shown similar tendencies in the past. In 2012, President Lee Myung-bak had agreed with Japan to sign the General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA). When the decision became public, he faced strong public backlash and the deal was eventually called off 50 minutes before the signing. President Lee was severely criticized for the lack of transparency in his decision. In fact, opposition to GSOMIA has continued to be strongly influenced by President Lee’s low public favorability.13 Ever since the postponement of GSOMIA in 2012, however, the public has been quite receptive to the idea of concluding a military sharing information pact with Japan. As Figure 6 shows, when Koreans were asked about the necessity of GSOMIA after it had been put on hold in 2012, more than half agreed that GSOMIA was necessary. When the agreement was finally signed between the two countries on November 23, 2016, domestic resistance was evident, but our survey results show that even then, 52.3% of respondents supported the deal while only 37.8% disagreed.14

Figure 6. Need for GSOMIA (%)15

Conclusion

Korea’s foreign policy faces a challenging year. Deteriorating US-China relations will put Korea in a precarious position, and China’s economic boycotts in protest against THAAD will only intensify concerns about how Korea should handle the situation. Yet despite the risks of Chinese retaliation, Koreans still valued their cooperation with the U.S. more than with China. When forced to choose between their most important security ally and their most important economic partner, they chose the United States. However, their preference of the U.S. was not simply determined by the pure calculus of security over economy. Rather, it was the culmination of proven trust and mutual values, such as democracy and an open economy. Even when ROK-China relations were at their peak, only a minority of Koreans saw Korea and China sharing similar values. In the minds of many Koreans, China is still a socialist country.

The most interesting result of the recent survey is how Koreans view THAAD and China. There was a significant drop in support for THAAD to the point where the difference between support and opposition were within the statistical margin of error. While this may be good news for China, the important point is that THAAD is a reaction to domestic politics rather than Chinese opposition. Contrary to popular belief, the China factor is a peripheral issue for Koreans when considering THAAD.

China’s negative reaction to THAAD has inevitably influenced how Koreans see China and even Chinese President Xi Jinping. In the January 2017 survey, favorability ratings for China and President Xi failed to recover from drops suffered at the end of 2016 (China: 4.31, President Xi: 4.25). If China continues its hardline policies toward Korea as retribution for the deployment of THAAD, the numbers could become much worse. Moreover, anti-China sentiment in Korea could shift public opinion in favor of THAAD, which would counter Chinese interests. Therefore, China needs to consider Korea’s public opinion and carefully manage how it responds to Korea’s decision on THAAD. At the same time, the Korean government must appropriately inform its public and reflect public opinion on sensitive matters like THAAD in order to regain the public’s trust and support.

Methodology

– Sample size: 1,000 respondents over the age of 19

– Margin of error: +3.1% at the 95% confidence level

– Survey method: Random Digit Dialing (RDD) for mobile and landline telephones using Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI)

– Period: See footnote of each figure/table

– Organization: Research & Research

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 1.

Special thanks to Mr. Benjamin Forney for his comments.

- 2.

Nicholas, Peter, Paul Beckett, and Gerald F. Seib. “Trump Open to Shift on Russia Sanctions, ‘One China’ Policy,” The Wall Street Journal. January 13, 2017. http://www.wsj.com/articles/donald-trump-sets-a-bar-for-russia-and-china-1484360380 (accessed on January 17, 2017).

- 3.

Asan regular surveys (Date: Jan. 2015 – Jan. 2017)

- 4.

Kim, Jiyoon, John J. Lee, and Chungku Kang. 2015. “Measuring a Giant: South Korean Perceptions of the United States,” Asan Report. Seoul: The Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 5.

Asan regular survey (Jan. 22-24, 2016); “Measuring a Giant: South Korean Perceptions of the United States,” Asan Report. Seoul: The Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 6.

Asan special survey (Nov. 22-24, 2016).

- 7.

Asan special survey (Aug. 16-18, 2016).

- 8.

Gallup Korea Daily Opinion (Date: July 12-14, 2016; Aug. 9-11, 2016). The Gallup Korea Daily Opinion results shared similarities with our survey results. According to Gallup, 50% in July and 56% in August supported THAAD. On the other hand, 32% in July and 31% in August opposed.

- 9.

Asan special survey (Date: Mar. 18-20, 2015; Feb. 10-12, 2016; Aug. 16-18, 2016; Sept. 21-23, 2016; Nov. 22-24, 2016). Our question wording changed following the government announcement to deploy THAAD. In our Mar. 2015 and Feb. 2016 surveys, we asked “What is your opinion on the argument that THAAD must be deployed to counter North Korea’s threat?” In our Aug.-Nov. 2016 surveys, we asked “What is your opinion on the agreement made by Korea and the U.S. to deploy THAAD in Korea?”; Woo, Jung-Yeop. “Korean Public’s Perception of THAAD,” Paper presented at the 2016 Korean Political Science Association.

- 10.

Asan special survey (Date: Mar. 18-20, 2016; Feb. 10-12, 2016; Aug. 16-18, 2016; Sept. 21-23, 2016; Nov. 22-24, 2016).

- 11.

Respondents were asked to rate their favorability of China on a scale of 0 (least favorable) to 10 (most favorable).

- 12.

Asan special survey (Date: Nov. 22-24, 2016).

- 13.

Friendhoff, Karl, and Kang, Chungku. 2013. “Rethinking Public Opinion on Korea-Japan Relations,” Asan Issue Brief. Seoul: The Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 14.

GSOMIA has not been a major issue of contention in Korea this time around.

- 15.

The date that GSOMIA was concluded (Nov. 23) was during our November survey. Therefore, the survey results do not reflect the Korean public opinion of GSOMIA in the post-agreement timeframe. Regardless, the support for GSOMIA has been widespread since 2012. Regarding Figure 6, it is important to note that the survey asked if GSOMIA was necessary/unnecessary, not whether respondents agree/disagree with GSOMIA.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter