▮ 2023 in Review: Easing International Confrontation, Persisting Domestic Balancing

In 2023, dominant powers shifted away from intense rivalry, opting to avoid excessive frictions in their pursuit of leadership in the international order. Despite the persistence of the confrontational structure between democratic powers led by the United States and authoritarian powers centered on China, they nevertheless sought to prevent the escalation of their rivalry into direct conflict. This was exemplified by the summit between U.S. President Joe Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping, held on the sidelines of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit in San Francisco in November 2023. In a press conference following the summit, President Biden remarked, “We should pick up the phone and call one another and we’ll take the call. That’s important progress.” President Xi also underscored the principle of coexistence, stating, “Planet Earth is big enough for the two countries to succeed.”

The series of visits to China by U.S. Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen in July 2023 also appeared to signify the willingness of both countries to manage the relations. Meanwhile, Russia and the United States did not enter into a direct conflict over the war in Ukraine. While maintaining its supportive stance toward Ukraine, the United States remained passive in its approach toward providing the large-scale military support needed for a Ukrainian counteroffensive, due to the opposition of the Republican Party. Simultaneously, Russia refrained from escalating its so-called “special military operation” into all-out war, avoiding large-scale ground warfare.

Nevertheless, it is unrealistic to expect the fundamental resolution of these conflicts, given that rivalries among dominant powers, such as the U.S.-China strategic competition, have evolved into a matter of values and systems. In reality, despite avoiding direct conflict, major powers opted to keep their counterparts in check by asserting control over their spheres of influence. Accordingly, major countries are making visible moves to pressure their rivals by establishing coalitions centered around themselves. This trend already began several years ago and cannot be considered unique to 2023, but it has become more prominent as the world returns to normalcy after the COVID-19 pandemic and the aforementioned coalitions are once again being reinforced through meetings between national leaders.

While strengthening its network of traditional allies and partners, the United States has concurrently pursued a policy of reinforcing ties with crucial allies in the Indo-Pacific region, where there is a lack of multilateral security cooperation organizations such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), by engaging in minilateral security arrangements including the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) and AUKUS—the trilateral security partnership between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the U.S. To date, the United States has made persistent efforts to maintain this strategic direction.

For example, a diverse range of topics were discussed during the Group of Seven (G7) summit held in Hiroshima, Japan, from May 19 to 21, including discussions on the war in Ukraine, diplomatic and security matters, economic security affairs such as the reinforcement of supply chains and infrastructure, the establishment of artificial intelligence (AI) governance, emerging security issues such as climate change, energy initiatives, and the environment. Notably, many of these topics were directly or indirectly connected to U.S.-China strategic competition. In the subsequent G7 Hiroshima Leaders’ Communiqué, the leaders of the G7 member states expressed their stance by stating, “We strongly oppose any unilateral attempts to change the status quo by force or coercion.” They further called for a peaceful solution to tensions across the Taiwan Strait involving China and Taiwan and also stressed the need to address human rights concerns within China.

In essence, these statements were tinged with criticisms against China’s current policies, as was the statement of the G7 leaders that they will enhance their strategic consensus against malicious activities, such as unlawful exercise of influence to undermine supply chains, espionage, and illegal information leaks, which can be interpreted to target China in practice. Although this communique acknowledged that China’s economic growth has contributed to the global economy, and emphasized a willingness to coexist with China, it can be seen to reflect the current state of strategic competition between the U.S. and China.1

This atmosphere continued at the NATO summit held in July 2023. Having condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and indicated their intention to counterbalance China’s foreign policy during the 2022 summit, NATO members declared that “China’s stated ambitions and coercive policies challenge our interests, security and values,” and further stated that the strategic partnership between China and Russia undermines “the rules-based international order” in the communique issued during the 2023 summit, which was held in Vilnius, Lithuania, in July 2023.2

The United States sought to mitigate the risk of military conflict with China while simultaneously engaging in more sophisticated deterrence in non-military domains. This strategy became notably apparent during the U.S.-China summit in San Francisco in November 2023. During the summit, the United States urged China to restore some military communication channels but made it clear that it had no intentions to make concessions on issues such as the economy and the environment. At the same time, the United States continued its efforts to bolster regional minilateral security cooperation. On March 13, 2023, the first face-to-face meeting of the AUKUS partnership between the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom was held in San Diego, and the Quad Leaders’ Summit was held in Hiroshima, Japan, on May 20, 2023.

However, the most significant event in regional minilateral cooperation in 2023 was the trilateral leaders’ summit involving South Korea, the U.S., and Japan, held at Camp David in the U.S. in August. Based on the improvement of relations between South Korea and Japan in early 2023, the United States successfully finalized its longawaited framework for trilateral cooperation in Northeast Asia. Through the “Spirit of Camp David” agreement, trilateral security cooperation evolved beyond mere summit meetings between leaders, establishing the groundwork for regular dialogues across diverse areas, including traditional security, economic security, and emerging security.

Meanwhile, U.S. efforts to foster collaboration among allies in the Indo-Pacific and Atlantic regions also continued. For example, the leaders of the four Asia-Pacific partners (AP4) of NATO—the non-NATO member states of South Korea, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand—were invited to the 2023 NATO summit held in Vilnius. All of these leaders represented countries in the Indo-Pacific region and had also participated in the 2022 NATO summit.3

However, such coalition-building efforts did not always proceed without challenges. The outbreak of the Israel-Hamas war in October 2023 was an event with the potential to significantly impact the U.S. strategic direction in the Middle and Near East region. Towards the end of the Donald J. Trump administration, the United States promoted reconciliation and cooperation between Israel and Islamic states in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, as exemplified by the Abraham Accords. Through these efforts, the United States sought to reduce its involvement in the region, deter antiAmerican countries like Iran and Syria, and concurrently endorse cooperation between Israel and Saudi Arabia.

Figure 1.1. G7 Hiroshima Summit

Source: Yonhap News.

When the Israel-Hamas war broke out, Qatar actively endorsed Palestine’s position, the United Arab Emirates (UAE)—while not explicitly supporting Hamas—contributed $20 million in aid to the Palestinians, and Saudi Arabia also expressed support for the Palestinians in response to the conflict. Although the UAE, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia did not overtly oppose Israel, the Israel-Hamas war may have significantly undermined the momentum of the Abraham Accords. This is in contrast to the solidarity demonstrated by Iran and Syria from the onset of the conflict by actively supporting anti-Israel and anti-American forces such as Hamas and Hezbollah, casting uncertainty on the future of coalition-building based on the U.S.-Israeli cooperation in the Middle and Near East region.

U.S. efforts to secure the participation of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries in a U.S.-centered coalition likewise achieved only partial success. While the United States faced limitations in assuring all Southeast Asian countries about the potential future benefits of a U.S.-centered coalition, it was successful in elevating the U.S.-Vietnam relationship to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (CSP) during President Biden’s visit to Vietnam in September 2023. As such, the United States has worked to incorporate ASEAN members into its coalition by focusing on bilateral relations with individual countries such as the Philippines, Vietnam, and Indonesia, rather than pursuing a more comprehensive engagement with ASEAN as a collective entity.

China also criticized the U.S.-centered coalition-building efforts and actively cultivated its own coalition networks. In 2023, China emphasized the stabilization of U.S.-China relations under the one-man rule of Xi Jinping, aiming to disrupt the U.S.-led anti-China coalition. At the same time, China broadened its collaborative relationships with the “Global South” by raising concerns about U.S. leadership and advocating for enhanced economic cooperation.4 China also devoted itself to expanding its influence by leveraging its economic influence in response to the strengthening of the U.S. network of allies and partners.

A major outcome of this strategy was the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), launched at the end of 2020. Although RCEP is an initiative led by ASEAN, China effectively assumed a leadership role in it through its active support. This can be attributed to the fact that, while RCEP is a multilateral cooperation organization involving the largest number of countries in the Indo-Pacific region, constituting 29 percent of global GDP, China represented 44 percent of the total GDP within RCEP as of 2019, not to mention that major U.S. allies, including South Korea, Japan, and Australia, are also signatories.

In addition, China announced its intention to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the successor to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), in 2021 and engaged actively in regional multilateral economic cooperation, aiming to proactively fill the void created by the absence of the U.S.5 China is also seeking to reap the benefits of coalition-building through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), an economic development cooperation initiative it has promoted since 2014. In October 2023, China hosted the third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in Beijing, following the previous forums in 2017 and 2019. Over 4,000 delegates from 140 countries took part in the third forum, with more than 90 countries sending heads of state and other high-level officials.6

Figure 1.2. 2023 Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation

Source: Yonhap News.

China has also been leading collaborative organizations that advocate multilateral cooperation on the surface, but which are in fact aimed at countering the United States, most notably the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). The SCO is a cooperative organization that defines terrorism, separatism, and extremism as the “three evils.” While it is ostensibly open to all countries that sympathize with its goals—it includes India, Pakistan, and other countries which take a neutral stance in U.S.-China strategic competition—in reality it tends to operate as a coalition of states against the U.S. In addition, it also serves as a means to strengthen the legitimacy of China’s internal policies, as the so-called “three evils” that it advocates encompassing independence movements of ethnic minorities and other resistance movements. One significant development at the 23rd SCO Summit, conducted virtually in July 2023, was the full SCO membership granted to Iran. Though the decision to admit Iran as a full member had already been made at the 2022 summit, this development held high symbolic importance given the ongoing confrontation between the U.S. and Iran.

Russia also established its own strategic coalition to bolster its international standing. Since the deterioration of relations with the West, Russia has been strongly criticizing the dominance of the U.S. governance structure and envisioning a multipolar world order founded on the coexistence between civilizations. To this end, Russia aims to expand the membership and enhance the roles and functions of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), the SCO, and the BRICS—an intergovernmental organization comprising Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. While aspiring for a prominent position in security matters as part of its leap as one of the pillars of the multipolar world order, in the finance and information sectors, Russia also seeks to establish a media system to counter Western influence and introduce an international monetary system designed to promote de-dollarization. To this end, Russia has been operating the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) since 2002, with the aim of maintaining control over the former member states of the Soviet Union.

In particular, Russia has exploited the war in Ukraine as an opportunity to further enhance its strategic and military solidarity with Belarus, including the redeployment of its tactical nuclear weapons there. However, Ukraine, Georgia, and Azerbaijan, which had experienced conflict with Russia or were discontented with Russia’s interference, withdrew from the CSTO. In addition, Russia failed to adequately support Armenia in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict that commenced between Azerbaijan and Armenia in 2020, leading to a decline in Russia’s influence within the CSTO. In a bid to reverse this situation, Russian President Vladimir Putin personally attended the CSTO summit in Belarus in November 2023.

In addition, Russia deepened its ties with North Korea following the North KoreaRussia summit by dispatching Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov on a visit North Korea in October, while President Putin simultaneously visited Beijing with an agenda to strengthen Russia’s strategic coalition with China. The relationship between Russia and China is noteworthy in this regard. While Russia maintains positive relations with China, it cannot entirely embrace its increasing dependence on China. Although diminishing this dependence on China is a challenging task, Russia attempted to restore relations with North Korea as a means to secure supply chains for ammunition and artillery, on one hand, and safeguard Russia’s interests in the Asia-Pacific region, on the other.

Concurrently, some countries are growing in prominence as they take a step back and adopt a neutral stance in the face of the competing coalition building by the United States, China, and Russia. The aforementioned “Global South” is a representative example, as these countries aimed to maximize their interests by refraining from taking sides and adopting an ambiguous stance on significant issues that could lead to tensions between the United States and China or between the United States and Russia. Even in 2023, countries in the “Global South” generally adhered to a neutral position regarding the war in Ukraine and U.S.-China strategic competition. Through this approach, they reinforced selective cooperation with major countries and assumed a passive stance towards participating in coalition-building efforts.

Throughout the “Global South,” there are regions in which both the United States and China hold a stake, but have failed to dedicate significant efforts, with ASEAN being a notable example. In the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy, ASEAN or Southeast Asia appeared to gradually lose its priority, as the Biden administration’s strategy for the region caused anxiety among ASEAN member states based on the impression that it preferred to deal with specific countries bilaterally rather than with the entire ASEAN bloc. China also failed to effectively leverage this vacuum. However, this appears to be a matter of priorities rather than an actual lack of interest toward ASEAN, which has nonetheless resulted in ASEAN appearing to be somewhat detached from U.S.-China strategic competition and coalition-building efforts.

▮ Characteristics of the Coalition-Building Competition

Recent coalition-building efforts by dominant powers are distinguishable from “alliances” in that their purpose is not limited to the military dimension, and they also differ from general partnerships in that member states in a coalition either expect exclusive advantages from their participation or are concerned about the disadvantages of non-participation. Most notable in this regard are the coalition-building efforts of the United States, which can be characterized by the following three characteristics.

First, the United States aims to maintain and strengthen its existing comprehensive multilateral cooperation networks while seeking and facilitating new avenues of minilateral cooperation. As highlighted above, the United States is seeking to reinforce its relations with the member states of the European Union (EU) and NATO in Europe, with a heightened focus on enhancing its cooperation with the latter following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Beyond Europe, the United States is consolidating coalitions among its allies and partners through minilateral cooperation involving three or four parties. Such efforts have already come to fruition with the formations of the Quad and AUKUS, with the Camp David Trilateral Summit in 2023 serving as the final piece of the puzzle for the Northeast Asian region. In addition, the U.S. is also strengthening the ties between its major allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific region and NATO. This suggests a concerted effort by the U.S. to link the Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions to establish a network of its allies worldwide.

Second, the U.S.-centered coalition-building strategy highlights a confrontation between democracy and authoritarianism. Compared to the past, the United States is placing greater emphasis on shared values and systems in building coalitions and this stance has led to an intensified clash between democracy and authoritarianism, prompted by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This is not unique to the Biden administration, given that the Trump administration had already raised the issue of governance systems in the U.S. strategic competition with China, labeling China and Russia as “revisionist” powers. The emphasis on coalitions based on shared values has persisted in 2023, mirrored in joint statements issued by the United States with its allies and partners. In this context, both China and Russia advocate against U.S. hegemony, presenting their own definitions and justifications for the concepts of democracy, human rights, and international order to defend their authoritarian regimes, thus deepening the clash of values among major powers.

Third, in the economic domain, “club-like” coalitions are being created that require certain qualifications for membership, rather than being inclusive and open. The United States seeks to move beyond security cooperation to comprehensive cooperation, emphasizing to its allies the importance of cooperation for “economic security,” but it is reluctant to engage in multilateral partnerships that could bring reciprocal benefits, such as Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). This stance is exemplified by the fact that it led the platform-like Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) but did not participate in the RCEP and CPTPP. The United States is also consolidating coalitions with its allies and partners through initiatives like the “Chip 4” alliance, aimed at reshaping supply chains in specific sectors. This strategic move is intended to prevent China and Russia from surpassing the United States in critical areas that will drive future growth, and to maintain U.S. leadership based on its qualitative military advantages. However, the United States is susceptible to the criticism that it is based on a selective variation of the “America First” policy, which is a potential impediment to U.S. coalition-building efforts, as is its reluctance to engage in inclusive multilateral coalitions.

In this context, China is also seeking to build coalitions centered on itself, based on the following characteristics. First, these coalitions hinge on comprehensive multilateral economic cooperation, leveraging China’s vast market and financial power. China is maintaining and expanding its influence over U.S. allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific region through economic multilateral cooperation, such as by signaling its willingness to join the CPTPP, while dissuading their participation in the U.S.-led “Chip 4” alliance or the IPEF. China also aims to strengthen its influence over countries in the Indo-Pacific, the Middle East, and Eastern Europe by establishing a network for development cooperation in alignment with its economic initiatives, notably through the Belt and Road Forum.

Second, China’s coalition-building efforts are intended to consolidate solidarity among authoritarian states. China capitalizes on the SCO to enhance its ties with countries outside the circle of U.S. allies and partners. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, China has sought cooperation with Russia, signaling its preparedness to play a mediating role. However, China has not officially denied the possibility of forming a North Korea-China-Russia trilateral coalition, based on strengthened ties between North Korea and Russia. Third, China is enhancing security cooperation with other countries without officially defining such cooperation as “alliances.” For instance, China has continued to expand its security cooperation with countries in the Middle East and Africa to counteract U.S. influence in those regions.

In response to these competitive coalition-building efforts among dominant powers, the “Global South” is striving to make its voice heard in a different way from the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) of the past. While the member countries of the NAM did not possess significant economic influence, the “Global South” has become a meaningful player in the global economy, albeit not quite at the level of China and the West, including the United States. For example, in 2002, the total gross domestic product (GDP) of the BRICS countries, most of which are members of the “Global South,” amounted to only a quarter of the U.S. GDP, but the bloc has since grown to the extent that it now rivals the G7 in total economic size and some analysts project it could overtake the G7 within the next 20 years.7 This implies that, unlike the NAM, which had little impact on the Cold War balance of power, the choices made by the “Global South” will be a non-negligible factor in the current race to establish coalitions.

While the NAM had somewhat anti-Western, non-socialist leanings, the “Global South” has no clear political affiliation. It cooperates with both the United States and the authoritarian bloc including China, and its political stance is not unconditionally neutral, but rather flexible on major international issues, depending on the situation and countries involved. In other words, the “Global South” tends not to act as a monolith. The actions of “Global South” countries are not collectively determined by any particular cooperative unit, which is another crucial difference from the NAM. The loose solidarity of the “Global South” was demonstrated at the BRICS Summit in August 2023 as well.

Although the BRICS countries are not all members of the “Global South,” its three members except Russia and China—namely Brazil, India, and South Africa—are all leading countries of the “Global South.” At the 2023 BRICS Summit, China and Russia advocated for a significant expansion of BRICS membership as a way to develop it into a coalition to counter the U.S. However, the attempt was met with opposition from India and South Africa, which were reluctant to see the BRICS transformed into more than economic cooperation with China and Russia’s influence expanding. In the end, only six new countries—Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE—were accepted as members at the 2023 BRICS Summit, among which only Iran is currently at odds with the U.S.

At the regional level, smaller coalitions are being established reflecting the concerns faced by each region. In the Middle East, U.S. influence is declining, while the former enemies of Israel and Arab states are now working together through the Abraham Accords. They are also cooperating with China by sharing COVID-19 prevention practices, promoting joint economic cooperation projects, and strengthening diplomatic ties, which does not necessarily indicate their desire to deviate from the U.S. sphere of influence. ASEAN is endeavoring to assert its voice by promoting the idea of “ASEAN Centrality,” but it retains concerns about the credibility of China and the U.S. Meanwhile, EU member states are consolidating their ties with the United States following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, though without turning their backs on China’s potential.

Competitive coalition-building efforts among dominant powers are taking place in various domains, as opposed to the political and military dimensions alone. This is exemplified by the race to form coalitions surrounding the reorganization of supply chains in the economic domain and the race to establish exclusive blocs for cooperation in science and technology. As demonstrated at the Camp David Trilateral Summit, these coalition-building efforts can even be extended to outer space.

The race to build coalitions presents a dilemma for many countries, and South Korea is no exception. It would be too costly to choose a coalition with any single country, and the situation surrounding the competitive coalition-building efforts can change depending on compromises among dominant powers. It is also possible that conflict between coalitions affects the security landscape across the region. For example, the enhanced military ties between North Korea and Russia would prompt the consolidation of the ROK-U.S.-Japan trilateral security cooperation and subsequent provocations by North Korea, which would escalate tensions in turn, or the strengthening of North Korea-China-Russia trilateral cooperation, which could lead to a crisis in the Taiwan Strait or the South China Sea.

▮ 2024 Outlook: Intensifying and Expanding Coalition Building

During the APEC Summit in San Francisco from November 15 to 17, 2023, U.S. President Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping met each other and expressed their commitment to preventing the U.S.-China rivalry from escalating into outright conflict and continuing to work together on issues such as climate change, combating the proliferation of narcotics, and artificial intelligence.8 This lends credence to the expectation that the coalition-building competition between the United States and China may be somewhat alleviated on the surface, but the two countries continued to espouse divergent views on issues related to traditional security, cutting-edge technology, and supply chains. This suggests that their coalition-building race is likely to accelerate in 2024. More than ever, the United States will seek to leverage coalitions centered on itself, since it is difficult for the country to respond unilaterally to formidable challenges, such as defending Ukraine, maintaining security commitments in the Taiwan Strait and the Korean Peninsula, and preventing the escalation of conflicts in the Middle East as the fallout of the Israel-Hamas war.

First, the United States will seek to expand the role and function of existing minilateral cooperation. In Northeast Asia, for example, the United States will place greater emphasis on stability in the Taiwan Strait and the Indo-Pacific region, in addition to addressing the North Korean threat through its trilateral security cooperation with South Korea and Japan. It will also consolidate the said trilateral cooperation in the domain of economic security, including supply chains. The United States will also endeavor to expand the role of the Quad from cooperation in emerging security areas to traditional security cooperation, despite the possible limitations imposed by India’s opposition. Furthermore, the United States will accelerate its efforts to expand membership in existing coalitions. Following Finland’s accession to NATO, the United States is expected to seek a path for Sweden to become a full member, while encouraging potential members to join AUKUS and other alliances.

In addition, the United States will establish coalitions in specific areas as needed, focusing on functional solidarity beyond geographic scope. The potential areas for such functional coalitions include intelligence, military logistics, defense, emerging technologies, and aerospace. Intelligence sharing is a representative function of these newly-emerging coalitions, as evidenced by the various intelligence-sharing partnerships centered on the United States, including cooperation with the existing “Five Eyes” member countries of the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, alongside the Quad and the ROK-U.S.-Japan and the U.S.-Japan-Philippines trilateral cooperation partnerships. Through these partnerships, the United States will be able to establish new intelligence coalitions.

In response, China is expected to continue undermining U.S. leadership in the international order and establish its own authoritarian coalitions in each region by expanding partnerships with developing and authoritarian states based on its technological and economic strength. First of all, China will seek to expand its influence by supporting the Arab states’ position in the Israel-Hamas war, and in the process, consolidate its political ties with these countries. As developing countries face greater needs for economic growth amid multifaceted global crises and economic downturns, China will endeavor to differentiate itself from the U.S. and establish coalitions with developing countries in the Middle East, Africa, and South America.

In the science and technology field, China has sought to develop its own innovative technologies in the face of intensifying U.S. pressure. Against this backdrop, in 2024, China is expected to utilize its innovative technologies to satisfy the high demand among developing countries to bridge the digital divide, thereby disseminating its own system as well as related policies and standards in Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Africa, the South Pacific, and South America, elevating its status and influence in its cooperative partnerships with developing countries.

Russia will also join this race for coalition building, sometimes in cooperation with China and sometimes on its own. As the war in Ukraine drags on, Russia is likely to take time to prepare for the rise of a new, post-war world order, rather than seeking a swift end to the war. Based on the hope that the protracted war will exacerbate war fatigue and thus weaken solidarity among Western countries that are supporting Ukraine—as well as the results of the upcoming U.S. presidential election and various other elections in EU countries that could lead to reduced Western support for Ukraine—Russia will actively engage in the race to build coalitions in pursuit of a multipolar international order that guarantees Russia’s sphere of activity with a focus on Eurasia, as well as enhanced cooperation with the “Global South.”. It may also become more willing to engage in military trade deals based on coalitions. In order to gain the upper hand in ceasefire or end-of-war negotiations with Ukraine, Russia could launch large-scale missile strikes or airstrikes, if not a ground warfare campaign, on major Ukrainian cities. This strategy is also likely intended to maximize its political impact in Russia ahead of elections scheduled for March 2024. This could help increase military proximity and solidarity between Russia and North Korea in early 2024, albeit for the short term.

With the declining approval rating of Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s administration, Japan is expected to maintain its existing policies based on cooperation and coalitions with the U.S., rather than pursuing major diplomatic shifts. In the domain of diplomacy and security, the main areas of focus will be military security, economic security, and cybersecurity, and particularly in terms of military security, Japan will seek to enhance its solidarity with partner countries to strengthen the liberal international order and achieve the goal of increasing its defense capabilities.

Throughout the Middle East in 2024, a new pattern of coalition building will emerge in response to reduced U.S. involvement in the region. The United States is likely to continue the “Abraham Accords” framework of managing regional affairs through improved relations between Israel and Arab states, rather than through direct engagement or intervention. However, as shown in the Israel-Hamas war, reduced U.S. involvement will amplify the discontent and anxiety of its traditional allies, such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Jordan, which would thus lead them to overcome their historic conflicts and eagerly seek opportunities to form new coalitions with Israel, Turkey, Egypt, and Iran. Once the military tensions provoked by the Israel-Hamas war subside, U.S. mediation toward détente in the Middle East will resurface and major countries in the region will begin to act accordingly since they recognize that strengthened ties with China do not mean that they can neglect relations with the U.S. Even in the case of Iran, although it claims to be the ringleader of an anti-American coalition in the region, it will nonetheless refrain from directly supporting countries engaging in anti-American movements. As a result, the Middle East will remain devoid of a clear winner in terms of coalition building, not even the U.S., China, or Russia, and thus see the complex and continuous reshuffling of local coalitions.

ASEAN will focus more on identifying opportunities for cooperation based on the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific (AOIP). While ASEAN will continue to base all cooperative efforts on the four areas of maritime cooperation, connectivity, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and economic and other possible areas of cooperation as specified in the AOIP, it faces a problem in the lack of momentum for internal cohesion within the region and external motivation for cooperation. This will increase the need for ASEAN to capitalize on the “Global South” as another network for its interests. If ASEAN enhances its identity either as part of the “Global South” or its partner and strengthens coalitions with the “Global South” countries, this may create a synergic effect with ASEAN’s hedging strategies against the established powers.

Likewise, EU member states will continue to grapple with entrenched issues. While their alliance with the United States has been largely restored following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, EU members recognize the need to reduce their dependence on the U.S., given the uncertainty of its domestic politics such as the upcoming presidential election and the possibility of Trump’s re-election, has become an obstacle in the way of further enhancing relations between EU members and the U.S. Although its relations with China have remained strained, the EU has not abandoned its partnership with China as it considers the Chinese threat to be less severe than that posed by Russia. As a result, EU countries have been shifting their strategy against China from “decoupling” to “derisking,” and will seek to alleviate some tension in their relations. While EU members remain vigilant against Russia, they have yet to develop a unified set of principles on how they will define their relations with Russia following the end of the war in Ukraine. In this regard, EU members are expected to pursue “open strategic autonomy” in 2024, redefining their relations with dominant powers such as the U.S., China, and Russia. In other words, based on their cooperation with the U.S., EU countries will seek a certain degree of assertiveness rather than unconditionally acquiescing to U.S.-centered coalitions. To this end, the EU will continue to form cooperative coalitions with countries in the “Global South” and the Indo-Pacific and make efforts to strengthen its voice on the global stage by expanding its membership and enhancing its internal solidarity.

Based on the outlook for each country’s strategies and policies related to coalition building, 2024 will be characterized by the following phenomena.

1. Coalition-Building Competition in Northeast Asia: A Microcosm of Global Trends

Northeast Asia is predicted to be a region where the coalition-building competition will be most pronounced in 2024. While the outcome of the 2024 U.S. presidential election remains a variable, the Biden administration is expected to continue the trilateral cooperation framework initiated during the Camp David ROK-U.S.-Japan Trilateral Summit and make the most of shared values and systems among the three countries. Consequently, a more conspicuous confrontation is anticipated between the ROKU.S.-Japan coalition and the DPRK-China-Russia coalition, which will be most keenly welcomed by North Korea. Having defined the current situation as a “new Cold War” already at the 6th Plenum Meeting of the 8th Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea in 2022, Kim Jong Un is poised to reap the benefits of the clash of coalitions by bringing China into its existing cooperation framework with Russia under the aim to advance its nuclear capabilities, thereby achieving the status of a “nuclear power,” while also resuming negotiations with the United States following the 2024 U.S. presidential election.

Despite the ostensibly confrontational stance, the true solidarity of this coalition remains uncertain, primarily owing to potential constraints within the DPRK-China-Russia cooperation framework. While North Korea has sought another patron by turning to Russia rather than engaging in negotiations with the United States, the nuclear technology transfers that North Korea wants are a significant burden for Russia. It also remains unclear whether Russia can provide substantial economic support for North Korea. As noted earlier, the military deal between the two countries could accelerate in early 2024. However, if Putin returns to power in the presidential election scheduled for March 2024 with a guaranteed term of office that will last until 2030, it is unclear whether he will commit to closer relations with North Korea. China, too, may exhibit caution in elevating DPRK-China-Russia cooperation from a symbolic gesture to a substantive military partnership. In addition, China will employ its relationships with South Korea and Japan to deter the advancement of the ROK-U.S.-Japan trilateral cooperation, a factor that will limit the progress of DPRK-China-Russia cooperation beyond a certain level.

In this regard, the response to North Korea’s nuclear development will be the area in which the clash between the ROK-U.S.-Japan and DPRK-China-Russia coalitions will be at its most evident. Even if China and Russia do not directly support North Korea’s nuclear development, they are unlikely to actively impede or alter North Korea’s policies, which will inevitably result in conflicts with the ROK-U.S.-Japan coalition over the imposition of stronger sanctions on North Korea’s nuclear tests or missile launches. The confrontation between the ROK-U.S.-Japan and DPRK-China-Russia coalitions will also resurface in relation to economic security concerns including the restructuring of global supply chains.

2. Continuation of Regional Disputes

The rivalry for coalition building among the U.S., China, and even Russia is expected to erode trust among major powers, further diminishing the possibility of mediation and compromise in regional conflicts. Consequently, even if there is an atmosphere of ceasefire or peace process in Ukraine or the Middle East, the risk of renewed conflict will nonetheless persist, while the temporary cessation of the conflicts will likely only come at a time when the ability of major powers to intervene in the conflicts is exhausted. In this regard, a fundamental resolution of the war in Ukraine and the Israel-Hamas war may not be guaranteed, even in the event of their simultaneous end. For instance, the Ukraine war could be rekindled at any time over issues concerning Russia’s recognition of the “annexed” regions, Ukraine’s NATO and EU membership, and its internal political dynamics. Similarly, the Israel-Hamas conflict remains susceptible to resumption over the Palestinian Authority’s control of the Gaza Strip.

Meanwhile, Taiwan and the South China Sea will demand heightened attention in 2024. Tensions in the Taiwan Strait, which have already been recognized as a potential conflict zone in the 2020s, are likely to resurface around Taiwan’s presidential election in 2024. Despite Beijing’s denial of any intent to directly invade Taiwan, it may opt to escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait if it perceives a violation of its “One China” principle. In this case, the region may witness tensions as high as those caused by U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in August 2022, especially around Taiwan’s presidential election in January 2024.

Tensions in the Taiwan Strait also carry significant implications for security cooperation among South Korea, the U.S., and Japan. The “Spirit of Camp David” statement, announced in August 2023, opposes any unilateral attempts to change the status quo through force or coercion in the Taiwan Strait. The degree to which South Korea, the United States, and Japan embody this principle will influence the likelihood of actual military conflict with China. While direct conflict between the ROKU.S.-Japan coalition and China and its allies is improbable, diplomatic frictions will be inevitable. In the event that North Korea exploits the Taiwan Strait conflict to stage provocations, subtle disagreements may emerge between South Korea and the U.S. over the prioritization of security commitments.

3. Competitive Courtship of the “Global South”

As previously mentioned, 2024 will witness competitive coalition-building efforts targeting the “Global South,” not only by the United States and China but also by Russia, ASEAN, and the EU. Various countries will engage with the “Global South” under the aim of (1) fortifying the strength of their respective coalitions (the United States, China, Russia), (2) enhancing their influence or representation within dominant power alliances (EU), or (3) securing autonomy as an independent coalition (ASEAN). This trend will accelerate collaborative efforts by dominant powers directed toward nations in the “Global South.”

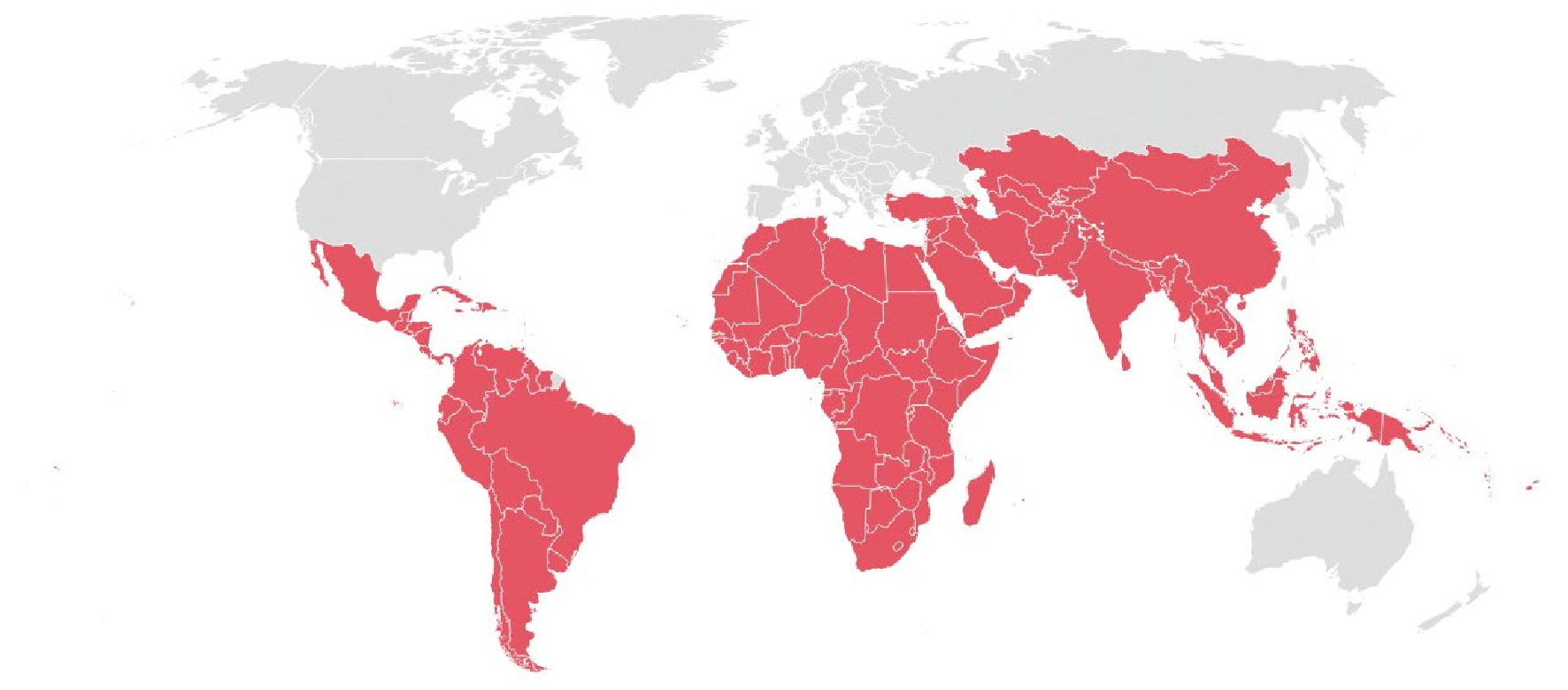

Figure 1.3. The “Global South”

Source: World Economic Forum.

However, the “Global South” refers to a specific group of states that are unlikely to coalesce under a unified direction or collective course of action. While there are some shared characteristics in terms of geopolitical location and economic potential, not all countries of the “Global South” maintain close relations with one another and each nation has its own foreign policy orientation, as seen in the aforementioned expansion of the BRICS. Consequently, in 2024, the “Global South” is expected to maintain a certain distance from the competitive efforts of dominant powers for coalition building, rather than supporting a specific coalition. Therefore, endeavors by major powers to construct coalitions are likely to focus on the major influential countries within the “Global South,” rather than seeking its collective cooperation. India, in particular, is expected to emerge as a competitive target due to the following factors: its neutral stance on the Ukraine conflict, its membership in the Quad, its traditionally cooperative relationship with Russia, and its avoidance of all-out conflict with China despite ongoing border disputes.

4. Leadership Challenges within Each Coalition

While dominant powers such as the U.S., China, and Russia will actively seek to establish coalitions centered on themselves, questions about their leadership within each coalition will be amplified in 2024. Firstly, the United States will face persistent controversy over its perceived lack of leadership, attributed to its passive stance on comprehensive multilateral security cooperation, economic unilateralism as demonstrated by the CHIPS and Science Act, along with the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), in addition to questions about its fulfilment of foreign security commitments. For example, if the conflict in Ukraine concludes with Russia’s annexation of occupied territory, the United States may become entangled in a renewed debate over its leadership, despite providing extensive support to Ukraine.

The forthcoming U.S. presidential election in 2024 also has the potential to spark intense discussions on U.S. leadership. In a nation currently marked by a lack of bipartisan consensus on crucial matters including in the security domain, the potential Republican presidential candidacy and return to power of former President Donald Trump could raise concerns about the coherence of U.S. foreign policy. In 2023, the United States was exposed in terms of its vulnerabilities in influencing allies when Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky clashed with the Biden administration over the scale and pace of military aid and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu disregarded U.S. requests to delay the Israeli military campaign in Gaza. Consequently, the United States’ restoration of its leadership will be a crucial factor in determining the strength of solidarity within the coalitions it leads.

Neither China nor Russia is exempt from leadership controversies, however. China’s domestic economic slowdown in 2023 poses a challenge to its efforts to construct a coalition based on economic strength. Moreover, its undermining of the UN Security Council’s authority on issues such as North Korea’s nuclear program despite being a permanent member could be a stumbling block for its reputation. Likewise, the economic crises suffered by partner countries of China-led economic cooperation initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative in the process of their implementation may give rise to amplifying concerns toward economic dependence on China as a result of cooperation with China. This will pose questions for the Chinese leadership about what safeguards they can provide.

Another critical variable for China will be its management of strategic competition with the United States. As evidenced by the policies of EU countries towards China, the EU is likely to seek economic benefits from cooperating with China. However, if China remains strategically opposed to the United States, the EU’s inclination to cooperate with China will diminish. Therefore, the effectiveness of China’s coalition depends on its ability to maintain strategic competition with the U.S. while avoiding excessive conflict.

Despite making territorial gains through its invasion of Ukraine, Russia has increased its perception as a threat to EU and NATO countries, exacerbating security concerns among the countries of the former Soviet Union. Additionally, depending on how the war in Ukraine is resolved, Russia’s domestic political situation will become increasingly unstable, even if Putin returns to power. As for Russia’s initiative to establish its own economic cooperation zone, its success will depend on the extent to which the country recovers from the various economic sanctions that it is under.

In the midst of leadership crises affecting all dominant powers involved in the coalition-building competition, tensions will rise between coalition leaders seeking to deepen and expand their coalitions, and coalition partners who are eager to safeguard their policy autonomy within these alliances. Consequently, dominant powers will actively take measures to reinforce the loyalty of the countries within their coalitions. For instance, the United States will prioritize cooperation with allies and partners based on their contributions to its coalitions, differentiating the implementation of its security commitments and science and technology cooperation accordingly. Similarly, China will employ a dual strategy of economic investment and economic retaliation to retain key potential coalition partners within its sphere of influence.

5. Escalation of the Crisis of Democracy

While the competition for coalition building among dominant powers is characterized by the clash of values and systems—specifically, democracy versus authoritarianism—it is ironic that the likelihood of a crisis of democracy has increased within democratic coalitions. Despite the Biden administration’s call for solidarity and unity among democratic systems, this approach to promoting values such as freedom and human rights has added to the reluctance of countries that are still transitioning to full democracy to align themselves with the U.S. For example, key players in the “Global South,” such as India and ASEAN member states, appear uncomfortable with the prospect of the U.S.-China strategic competition evolving into a debate over governance systems. This sentiment is mirrored in Latin America, a region that the United States has traditionally seen as under its influence.

In seeking to overcome the issue of promoting democratic values posing an obstacle to expanding their coalitions, major powers face the dilemma of having to either overlook the erosion of democratic principles in potential cooperation partners or engage with quasi-authoritarian states. Israel is a case in point. Although Netanyahu implemented anti-democratic policies such as attempts to weaken the judiciary after forming a radical right-wing coalition, the Biden administration has consistently supported the Israeli government during the Israel-Hamas war. When the strategic competition between the United States and China evolved into a contest of values and systems, the United States criticized “revisionist” forces for undermining the international order and attributed their problematic behavior to their political systems. However, this rationale fails to justify the United States’ support for the Netanyahu administration, which continues to act in violation of democratic principles. The challenge for the United States to bolster solidarity among democracies while accommodating anti-democratic allies and partners is anticipated to continue into 2024.

The crisis of democracy can be further compounded by the fact that the United States is not an exemplar of democracy itself in its domestic politics. The ideological divide and extremism within the U.S., which began to manifest during the 2020 U.S. presidential election, are likely to resurface or even intensify during the 2024 presidential election, which will leave lasting scars regardless of the outcome.

6. Catalysts of a Nuclear and Space Arms Race

The competition among major powers to build coalitions is poised to inevitably trigger an arms race. Securing an advantage in strategic competition requires not only military superiority over rivals but also the ability to serve as an arsenal for allies and partners. Indeed, with the onset of strategic competition between the U.S. and China, both nations have entered into a competitive arms race, striving for military superiority in both quantity and quality. Russia has also become more discerning and focused on developing military and technological capabilities comparable to those of the United States. A notable aspect is that this arms race may extend into the nuclear realm. The United States has explicitly expressed its intent to gain nuclear superiority over Russia and China by withdrawing from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) in 2019 during the Trump administration. Likewise, Russia withdrew its ratification of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) in November 20239—a move that could be interpreted as a declaration of its readiness to engage in a nuclear arms race with the U.S.

Given Russia’s threat to use nuclear weapons in the Ukraine war, its entry into a nuclear arms race with the United States—its primary nuclear power rival—signals a shift to more perilous times. China is also becoming a participant in the nuclear arms race, with the United States projecting an increase in China’s nuclear warheads from the current level of 400 to 700 by 2027 and to 1,500 by 2035.10 At present, there is no new agreement on nuclear arms control to replace the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaties (START) signed between the United States and the former Soviet Union. Prospects for a new START agreement, previously discussed between the United States and Russia in the 2000s, seem unlikely in the near term due to China’s entry into the nuclear arms race and Russia’s refusal to ratify the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). In 2024, the trajectory of the nuclear arms race may overshadow voices advocating for arms control.

In addition to the nuclear arms race, a discernible competition is unfolding in space. The United States, Russia, and China have already initiated efforts to leverage the space domain for military purposes, and in 2023, India made significant strides in space development by successfully landing Chandrayaan-3 lunar mission on the Moon. While space development currently revolves around individual initiatives rather than collaborative efforts among coalitions or alliances, there is ample possibility of a future space development coalition among allies and partners. As the military rivalry among major powers extends into the space domain, the logic behind alliances and military coalitions will also apply to this domain as well. While the formation of such a coalition may not be immediately evident in 2024, there is a plausible possibility of personnel or information exchanges between allies in preparation for a potential space coalition.

7. Bleak Prospects for International Cooperation in Emerging Security Areas

The ongoing competition for coalition building has cast a somber outlook on cooperation in emerging security areas, which had traditionally served as a nexus among major powers. This trend is expected to persist into 2024. Despite the United States and China’s commitment to cooperate on climate change and other issues at the San Francisco Summit in November 2023, there is limited motivation for major powers to forge a consensus on emerging security issues such as narcotics, new forms of terrorism, climate change, low-carbon green growth, and emerging infectious diseases, as these concerns are increasingly reduced to instruments for mutual deterrence rather than shared challenges.

Instead, yet another coalition-building competition is likely to emerge, particularly in the cyber domain. Although cyberspace has conventionally been regarded as immune to traditional geopolitics, this is only the case for the private sector, whereas at the government level, it is inevitably influenced by traditional geopolitics as information management and dissemination in the cyber domain reflect the nature of a given system of governance, be it democratic or authoritarian. As a result, cooperation on cybersecurity and information sharing will be strengthened among coalitions of states with similar values and systems, especially cyber cooperation among open democracies that are vulnerable to cyberattacks. In the area of economic security, the competition for coalition building is also expected to accelerate in 2024. In particular, U.S. efforts to build bilateral and multilateral coalitions on key technologies will gain momentum and become a driving force behind the formation of economic blocs.

In 2024, South Korea will face a complex set of choices in the ongoing coalition-building competition. North Korea will strengthen its role within the authoritarian coalition, envisioning that the confrontation between “democracy and authoritarianism” and that between the ROK-U.S.-Japan and DPRK-China-Russia coalitions will work in its favor to sustain its regime and system. Russia and China, in turn, will seek to use North Korea’s active participation in authoritarian coalitions to enhance their own diplomatic and military influence. It is concerning, however, that the United States, which leads the democratic coalition, may struggle to provide satisfactory leadership amid domestic divisions and electoral uncertainties. What is more, the United States is likely to demand greater sacrifices from its allies and partners within its coalitions in order to revive the U.S. economy—a critical issue in the upcoming presidential election. The apparent reluctance of the U.S. to expand its security and military commitments within coalitions while demanding greater contribution and even shirking the economic burdens of coalitions to its major allies will prompt its key allies, including NATO members, to reevaluate their positions within the coalitions, to which South Korea will be no exception.

- 1. “G7 Hiroshima Leaders’ Communiqué,” The White House, May 20, 2023.

- 2. “Vilnius Summit Communiqué,” NATO, July 11, 2023.

- 3. In 2022, Georgia was also invited.

- 4. The “Global South” refers to countries located at lower latitudes in the Southern and Northern Hemispheres. However, in some instances, the term collectively refers to all countries in the region based on their geographic location, while in other cases, it specifically indicates countries with the potential for substantial growth in the future among those located at low latitudes, such as India, Indonesia, and Brazil.

- 5. The TPP was a multilateral trade agreement signed in 2015 by countries including the U.S., Japan, Australia, Canada, Peru, Vietnam, Malaysia, New Zealand, Brunei, Singapore, Mexico, and Chile. Although initially launched with the aim of promoting economic cooperation and integration in the Indo-Pacific region, this partnership also contained strategic intentions to contain China. However, the U.S. withdrew from the TPP in 2017 after the election of President Trump, following which the remaining TPP members initiated the CPTPP with the goal of cooperation, mirroring the objectives of the previous partnership. Even after the inauguration of the Biden administration, the U.S. has remained reluctant to join the CPTPP.

- 6. “One Day Before the China’s Belt and Road Forum, Delegations from Different Countries Arrive in Beijing One After Another,” Yonhap News, October 16, 2023; “Over 90 countries confirm participation in One Belt One Road summit: Chinese MFA,” TASS, September 7, 2023.

- 7. BRICS is an acronym for Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, and has become a cooperative group of countries since South Africa joined its predecessor known as BRICs in 2010.

- 8. “Biden, China’s Xi will discuss communication, competition at APEC summit,” Reuters, November 18, 2023.

- 9. The CTBT is an international treaty that prohibits nuclear testing across all domains, encompassing the atmosphere, underground, and space. The prohibition on nuclear testing is regarded as a commitment to refrain from upgrading existing nuclear weapons or developing new ones. Although the United States became a signatory to the CTBT in 1996 when it was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly, the U.S. Senate declined to ratify it in 1999. Russia, on the other hand, remained a party to the treaty until 2023.

- 10. “Pentagon sharply raises its estimate of Chinese nuclear warheads,” Reuters, November 4, 2021.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter