Introduction

Currently, one of the major concerns for most countries in the Indo-Pacific region, including South Korea, is the strategic competition between the United States and China and the choice between the two powers. Less attention has been paid to secondary partners other than these two countries. Research on cooperation with powers besides the United States and China, i.e., third-party cooperation, is challenging to find in South Korea. This issue brief examines South Koreans’ views of the U.S. and China, which countries or regions they would choose if they partnered with a ‘third party’ other than the U.S. and China, and analyses how and why respondents’ choices for third-party cooperation, including the EU, ASEAN, and Japan, vary by age, ideological orientation, and perceptions of the U.S. and China.1

According to the analysis, South Koreans ranked the European Union as the most important partner, other than the U.S. and China. Interestingly, after the EU, ASEAN and Japan were the next most important countries or organisations. There were significant differences in respondents’ choices based on characteristics, such as age, political orientation, and perceptions of the U.S. and China. While the majority of respondents chose the EU as a third partner, the choice of ASEAN and Japan varied by respondent characteristics.

This finding has important implications. First, while there are many surveys on the choice between the U.S. and China domestically, few shed light on Korea’s cooperation with third parties. Given South Korea’s growing power, it is necessary to diversify its strategy beyond the U.S. and China, and this requires separate research and interpretation of South Koreans’ perceptions of third partners. It also seems that the perception of ASEAN in South Korean society is more often a preferable alternative to a less favourable option than a choice based on its own merits. This is a challenge for Korea’s public diplomacy toward ASEAN and ASEAN countries’ public diplomacy toward Korea.

Korea’s Choice between the US and China

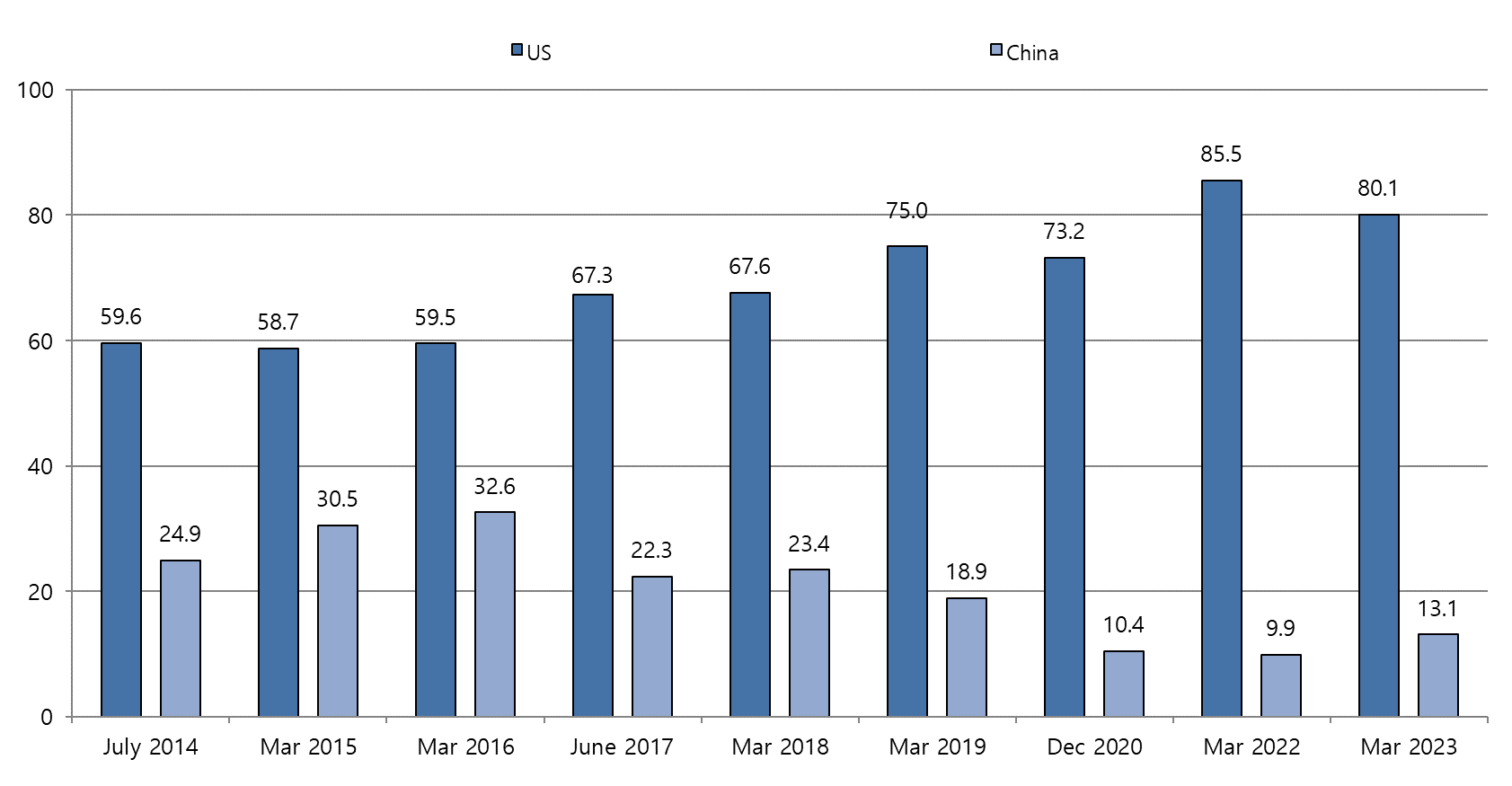

As past Asan Institute surveys have shown, South Koreans favour the United States over China as their primary partner. In 2022, 85.5% of South Koreans chose the United States, compared to 9.9% who chose China. This was no different in 2023. 80.1% of South Koreans chose the United States, while only 13.1% chose China. This trend has been consistent since 2014. The percentage of respondents choosing China reached the 30% mark twice in 2015 and 2016 but remained in the 20% range before and after that. Recently, this number has dropped to around 10%, indicating a more pronounced U.S. bias among South Koreans.

This is because the U.S. has allied with South Korea for the past 70 years, and the U.S. supply chain reshuffling centered on semiconductors and batteries significantly impacts our economy. The recent drop in China’s favorability is due to North Korea’s frequent and intense provocations, which emphasize the importance of the U.S.-ROK alliance as the backbone of South Korea’s security.

[Figure 1] Korea’s Choice between the United States and China2(%)

Most South Koreans were optimistic about bilateral relations between the U.S. and South Korea from 2013 to 2023 (min. 57.2%, max. 88.3%). Over the same period, the percentage of South Koreans who viewed the United States as necessary for security was much higher than the percentage who viewed China as important, with a minimum of 56.6% points and a maximum of 81.6% points gap. On the economy, after the deployment of the U.S. Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system on the Korean Peninsula in 2017 and China’s subsequent economic retaliation, South Koreans chose the U.S. by a minimum of 16.4% points and a maximum of 27.9% points, from a low of 48.7 percent to a high of 60.1 percent, outpacing China, which remained in the 30s.3

Korean Perception of Third Parties

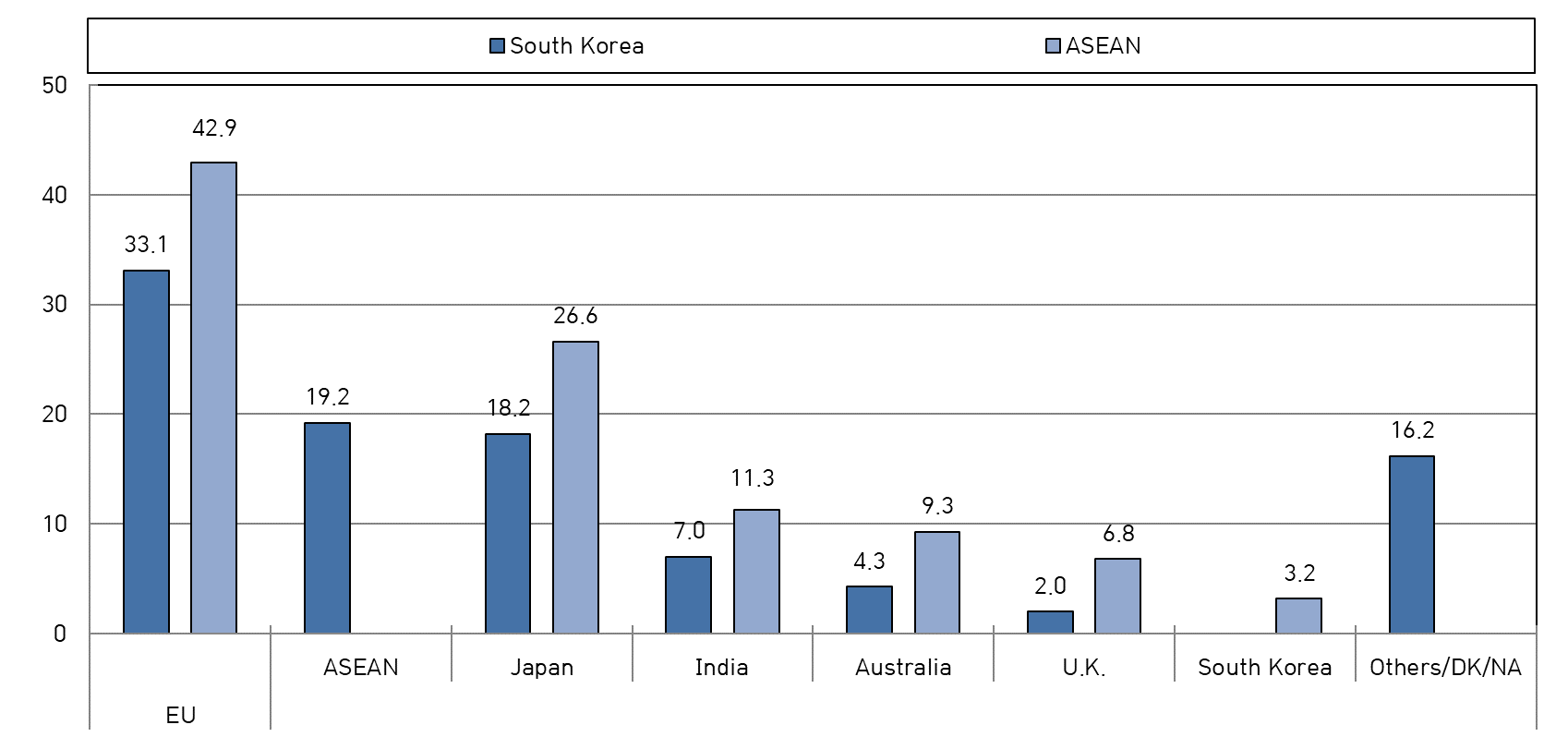

We examined South Koreans’ choices for partners other than the U.S. and China (see Figure 2). In response to our question, “In your opinion, which of the following countries should South Korea strengthen cooperation with, in light of the uncertainty of the U.S.-China strategic competition?” 33.1% of South Korean respondents identified the European Union as a priority partner. As shown below, the EU was the most popular choice for a third partner, regardless of gender, political orientation, or perception of the US and China. Despite the geographical distance between Korea and Europe and the ambiguity of Europe as a region or regional organisation, Koreans traditionally view Europe as a group of developed countries and, thus, an important partner for cooperation.

After the EU, South Koreans chose ASEAN (19.2%) and Japan (18.2%), followed by India (7%), Australia (4.3%), and the United Kingdom (2%). Notably, the percentages of Koreans who chose ASEAN and Japan are similar at around 19%. This means that Koreans consider ASEAN as important as Japan, despite ASEAN not being one of the four major powers surrounding Korea. South Koreans perceive ASEAN as an organisation of developing countries and do not consider it an important global actor. Nevertheless, the fact that ASEAN is seen as a third partner after the European Union is significant. The New Southern Policy, the increased trade and investment between ASEAN and Korea over the past decades, and ASEAN’s emergence as an alternative economic partner to China may have changed Korean perceptions of ASEAN. On the other hand, Koreans’ lower rating of Japan’s importance may result from years of deteriorating bilateral relations and deteriorating domestic public opinion in the wake of Japan’s economic retaliation policies against South Korea, including export control measures.4

[Figure 2] Choice of Third Partners: South Korea vs. ASEAN (%)

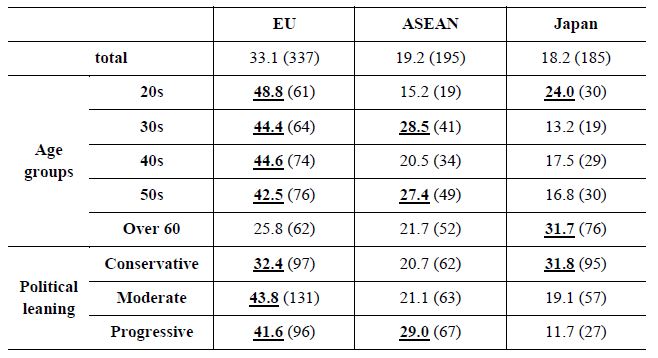

Perceptions of third parties by demographic characteristics

South Koreans’ perceptions of third-party cooperation partners by demographic characteristics showed significant differences by age group and political orientation. All age groups except those aged 60 and older identified the EU as an important partner. More than 40% of those in their 20s and 50s identified the EU as an important third partner. In contrast, those in their 60s were most likely to choose Japan (31.7%).

Interestingly, those in their 30s and 50s chose ASEAN over Japan after the EU. The gap between ASEAN and Japan for those in their 30s and 50s is quite large, 10-15% points. Those aged 60 and over and those in their 20s chose Japan as the second most important third partner after the EU, with 31.7% and 24%, respectively. Notably, the older age group (60+) saw Japan as an important partner; those in their 30s and 50s chose ASEAN over Japan, and those in their 20s and 60s chose Japan over ASEAN.

[Table 1] Choice of Third Partners by Demographic Characteristics5 (%, (n-size))

The choice of Japan by those in their 60s and older can be explained by the fact that they have an image of Japan as a developed country before the “lost 30 years”. They also seem to value the EU less than other age groups due to the geographical distance to Europe. Meanwhile, the higher percentage of ASEAN among those in their 20s may be due to the recent development of ASEAN-Korea relations and the growing strategic importance of ASEAN.

In general, younger people are more informed about international relations and international affairs, so they were expected to see ASEAN as a more important partner. However, the respondents did not confirm this hypothesis. Instead, they viewed the European Union as important and Japan as more important than ASEAN, unlike those in their 30s and 50s. This may be because, unlike older generations, younger people have overcome the geographical distance and do not see the EU as a distant partner. The fact that younger people are more active in consuming Japanese culture may also have influenced their perception of Japan as an important partner. On the other hand, Koreans in their 30s and 50s did not value cooperation with Japan largely because of a nationalistic view of Korea-Japan relations, marked by historical issues, territorial issues, and Japan’s economic coercion measures.

The choice of a third partner also varied by political orientation. Conservatives were more likely to choose Japan (31.8%) than respondents of other ideological leanings – 13% points higher than moderates and more than 20% points higher than liberals. On the other hand, they are less likely to choose the European Union by less than 10% points compared to moderates and liberals. Liberals are most likely to choose ASEAN (29%), while around 21% of conservatives and moderates choose ASEAN. Meanwhile, among liberals, only 11.7% chose Japan. As with the age groups, South Koreans, regardless of their political leanings, chose the EU as the most important third partner (43.8% of moderates, 41.6% of liberals, and 32.4% of conservatives).

There are several possible interpretations of the above results. First, the higher proportion of conservatives choosing Japan may reflect a traditional view of Japan, namely that it is a developed country, economically important, and that Korea-Japan cooperation is important in Korean Peninsula issues. In addition, the high percentage of conservatives who chose Japan may be due to the overlap between the over-60s and conservatives.

In contrast, liberals were less likely to see Japan as an important partner, choosing ASEAN over Japan. Two interpretations are available. First, liberals are more nationalistic than Koreans of other political orientations. The issues of history and economic conflict between Korea and Japan influenced their preference for ASEAN over Japan. Second, the Moon Jae-in administration, considered to be politically progressive, actively pursued the New Southern Policy targeting ASEAN and India. Given that strengthening ties with ASEAN was a key foreign policy legacy of the Moon administration, it is possible that progressive voters are more interested in ASEAN and more aware of the importance of ASEAN.

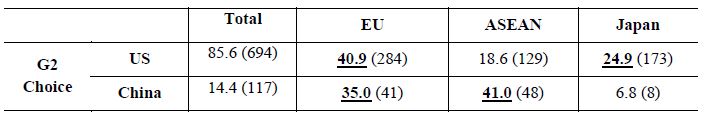

Perceptions of third parties depending on the choice between the US and China

Table 2 shows the cross-section of responses to a third partner by South Koreans’ choice of U.S.-China strategy. We used a binary choice question that asked respondents whether South Korea should cooperate more with the U.S. or China.

Those who chose the U.S. also chose the European Union as a third partner (40.9%). Next, 24.9% chose Japan. While the number of respondents who chose China as a strategic partner is small (n=117), those who chose ASEAN (41%) and EU (35%) were within the margin of error. The choice of Japan was in the single digits (6.8%). While the number of cases is small and should be interpreted with caution, those who chose China tended to choose an alternative to the traditional alliances or partners of the United States and Japan. This may have led them to choose ASEAN and the European Union over Japan as third-party partners. The Moon administration’s emphasis on the importance of ASEAN through its New Southern Policy may have contributed to their view of ASEAN as equally as important as the EU.

[Table 2] Choice of third partner depending on the choice of US and China6 (%, (n-size))

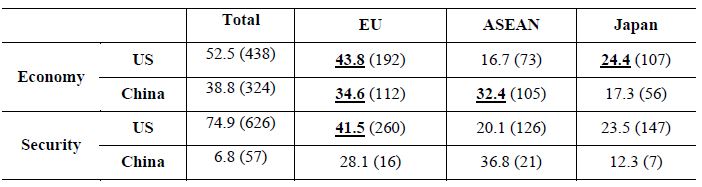

Table 3 shows the choice of third-party partners according to whether they consider the United States, China, Japan, Russia, or North Korea important to our security and economy. For the analysis, we only used the sample that selected the United States and China. Analysing the economic questions first, we found that the European Union was the preferred choice regardless of respondents’ preference for the U.S. or China. Second, respondents who chose the U.S. tended to choose the EU, followed by Japan, and those who chose China tended to choose ASEAN, meaning that respondents who chose China were more likely to choose ASEAN than the EU as a third partner.

The respondents that chose China preferred the EU (34.6%) and ASEAN (32.4%) as a third partner, but they were within the margin of error. Only 17.3% of them chose Japan. Those who see China as more important than the US to our economy are likely to have chosen it based on Korea’s economic dependence on China. These respondents may have been thinking about the uncertain future of the Chinese market and potential alternatives if China becomes a security threat to Korea. Therefore, they may have chosen ASEAN, which was mentioned as a possible economic alternative to China, as a third partner.

The security question results were similar to those for the U.S.-China strategy choice in Table 2. The choice between the U.S. and China on security was more biased in favour of the U.S. than the overall U.S.-China choice. As noted earlier, caution is needed to interpret the choice of China since the sample size is small. First, those who said the U.S. was necessary for security saw the EU (41.5%) as the most important third partner. The percentages for Japan (23.5%) and ASEAN (20.1%) were similar. On the other hand, those who viewed China as important for security were more likely to choose ASEAN (36.8%). However, the sample size (57 respondents) is small, and the difference among the EU, ASEAN, and Japan is not statistically significant.

[Table 3] Choice of Third Partner by security/economic importance of G27 (%, (n-size))

Regardless of whether South Koreans view the US or China as more important, they generally see the EU as a third partner. This is not surprising. Interestingly, those who viewed China as necessary for the economy and security were almost as likely to view ASEAN as being as important as the EU. Of course, it is unlikely that they chose ASEAN because of the regional organisation’s military, diplomatic, or strategic weight. The respondents who viewed China as important would have chosen other options than Japan or the EU, which are generally aligned with the United States regarding security.

Conclusion

A key question that this study tries to address is which countries or regions are important to cooperate with other than the United States and China. Of course, the two countries that exert the most influence over South Korea, the United States and China, are arguably the most strategically important partners. However, it is not recommended to devote all South Korea’s diplomatic resources to these two countries, as overdependence limits our autonomy. In this regard, it is important to identify a third partner other than the US and China. This question is not often asked in South Korea. However, as the scope of South Korea’s foreign policy expands, solidarity and cooperation with third parties beyond the US and China must be considered, and it is necessary to conduct a separate survey on South Koreans’ perceptions of third partners in the future.

In the survey on the perception of third partners, including the EU, Japan, and ASEAN, it is notable that a sizable number of Koreans chose ASEAN. In terms of demographics, those in their 30s and 50s, as well as centrists and progressives, chose ASEAN, not Japan, as their third partner after the EU. Given that ASEAN was ahead of Japan in terms of age and political orientation, this may reflect the Moon administration’s implementation of the New Southern Policy and, subsequently, the recognition of the importance of ASEAN, and relatively strong antipathy toward Japan. When choosing a third partner other than the U.S. and China, respondents who viewed China as important for economic and security reasons preferred ASEAN to Japan. However, this requires a nuanced interpretation. Rather than viewing ASEAN as a force similar to China or as an extension of China, this group of respondents may see ASEAN as a market that can complement China.

What is disappointing is that ASEAN has not been able to fully establish itself as a third partner with its own competitiveness. Those who chose ASEAN as a third partner may have done so as a counterbalance to avoid other options. In particular, the antipathy towards Japan, or the choice of ASEAN as an alternative to Japan that aligns with the United States, suggests that South Koreans have not yet fully acknowledged the merits of ASEAN. In other words, the importance of ASEAN has not yet been widely recognized in South Korea compared to the extent of economic ties and socio-cultural exchanges between ASEAN and South Korea. This is a challenge not only for Korea’s ASEAN policy but also for ASEAN countries’ public diplomacy toward Korea.

This article is an English Summary of Asan Issue Brief (2023-19).

(‘미중 경쟁 속 한국인의 제3 협력대상 인식: 높아진 아세안의 중요성’, https://www.asaninst.org/?p=90518)

- 1. Survey method of cited data are as follows: Sample size: 1,000 respondents over the age of 19, Margin of error: ±3.1%p at the 95% confidence level, Survey method: RDD for mobile and landline telephone interview (CATI), Period: March 13~15, 2023, Organization: Research & Research.

- 2. Asan Institute for Policy Studies (2023). South Koreans and Their Neighbors 2023. Survey Report. Seoul: Asan Institute for Policy Studies. https //www.asaninst.org/contents/south-koreans-and-their-neighbors-2023/

- 3. J. Kim∙C. Kang∙G. Ham (2022). South Korean Public Opinion on ROK-U.S. Bilateral Ties. Asan

Report. Seoul: Asan Institute for Policy Studies. We updated the data that collected in March 2023. - 4. This survey was conducted in March 2023, before the Korean government’s efforts to improve relations with Japan were in full swing. At the time of writing, South Koreans’ views of Japan are still unfavorable due to the release of contaminated water from Fukushima. However, it is possible that South Koreans’ views on Japan as an important partner have changed somewhat.

- 5. In Table 1, we only listed top 3 choices including EU, ASEAN, and Japan in the question asking respondents to pick the third partner other than the U.S. and China. The test statistics of cross-tabulation are as follows: Age group x2=62.991, df=20, p<.05, Political leaning x2=43.752, df=10, p<.05.

- 6. Sample size of the cross-tabulation in Table 2 is 811, which excludes no opinion such as “Don’t know” and “No answer.” And the test statistics are as x2=39.754, df=5, p<.05.

- 7. Table 3 shows the third partner choice by the most important country for South Korean economy and security (Question: “Which country is the important for South Korean economy/security?”). Sample sizes of the cross-tabulation in Table 3 are economy 834, and security 836. The test statistics are as follows: Economy x2=59.238, df=25, p<.05, Security x2=39.330, df=20, p<.05).

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter