“Nothing that he does is indifferent. His friendships, his relaxations, his behavior towards his wife and children, the expression of his face when he is alone, the words he mutters in sleep, even the characteristic movements of his body, are all jealously scrutinized. Not only any actual misdemeanor, but any eccentricity, however small, any change of habits, any nervous mannerism that could possibly be the symptom of an inner struggle, is certain to be detected. He has no freedom of choice in any direction whatever.”

George Orwell, 19841

Arriving in Shanghai last December, I struck up an unexpected conversation with my taxi driver. Stuck in traffic, the driver pointed to a prominent electronic scoreboard on the side of the road displaying car plate numbers and asked if I knew what it was. Interpreting my silence as an invitation for soliloquy, he said: “If you honk your horn in Shanghai, your car plate number will be displayed in one of those electronic scoreboards. This is to publicly shame you.” I had no clue that Shanghai had, as of 2007, prohibited honking, ostensibly to reduce noise level in the city.2

I asked, “what happens if you have to honk to avoid accidents?’ The driver shrugged, “There is nothing you can do. You just have to be patient and wait for others. But you cannot honk, unless you want to pay a fine.” He bemoaned that the penalty for honking used to be 200 RMB (about $30), but with the new technical system in place since last September, additional penalties would kick in. Under the new electronic tracking and monitoring system, any transgressor would not only pay a fine, but one’s car plate number would be tracked and displayed on the electronic scoreboard.

This public registering of honkers is a small part of a larger social credit system that Chinese authorities have begun to implement across the country. What the taxi driver in Shanghai did not know was that horn honking would accrue him negative points under this new system. This in turn would make his life more difficult as he would face greater obstacles in obtaining bank loans, securing employment, travelling abroad, and getting his children admitted to good schools. On paper, the social credit system appears to be a modified version of an individual’s credit score. But scratch the surface and a disturbing truth emerges. The term, social credit system, is a misnomer. This has nothing to do with credit; it has everything to do with control. Marrying algorithms to big data, the Chinese government seeks to inculcate a higher standard of morality and tighten its control over the people.

The words sound benign. On June 14, 2014, China’s State Council published a planning outline for the construction of a social credit system (2014-2020): “a social credit system is an important component part of the Socialist market economy system… It is founded on laws, regulations, standards and charters. It is based on a complete network covering the credit records of members of society and credit infrastructure.”3

Under this new system, all Chinese citizens are to be rated in four main areas – administrative affairs, commercial activities, social behavior, and the law enforcement system.4 The government plans to establish a mechanism for reward and punishment by 2020.

The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) is slated to execute the new plan. Local governments at the provincial and municipal level are setting up their own social credit system, with NDRC approval. According to the plan, information collected from local governments would be merged into a single centralized system to create a comprehensive list of data on Chinese citizens. The target deadline is 2020. In November 2016, Lian Weiliang, the deputy head of NDRC, noted that the social credit system has connected 37 government departments and collected more than 640 million pieces of credit information.5 He added that 4.9 million people have been prohibited from air travel and 1.65 million people barred from trains due to bad credit.

How would this social credit system work in practice? A citizen would earn positive points by settling outstanding bills on time, engaging in volunteer work, and visiting parents often. The standards and criteria for the social credit system differ slightly across the country but they are all approved by the NDRC. In essence, the higher one’s points, the more benefits one earns. Government support for starting a business, increased chances to book a fancy hotel, permission to travel abroad, obtaining school admission and scholarships are some of the benefits that the government touts for the new social credit system. In other words, the social credit system is consolidating a wide range of information on every citizen in China and using it to reward or punish personal behavior, and thus, ultimately influence and control the lives of people. This is social control par excellence.

Unlike the Fair, Isaac, and Company Score (FICO)6 used by the vast majority of banks and credit grantors in modern economies, such equivalent credit system is unavailable in China. Wen Quan, a vocal blogger on technology and finance, writes: “Many people don’t own houses, cars or credit cards in China, so that kind of information isn’t available to measure. The central bank has financial data of some 800 million people, but only 320 million have a traditional credit history.”7

This absence of credit “worthiness” is reflective of the absence of faith in government, a trait that is deeply rooted in Chinese culture and history. Lack of faith in government policies and poor transparency have been fixtures in Chinese society for most of its history. These days, news of fraud, inadequate food safety, and corruption are widespread. The most revealing example of a food safety incident was Beijing’s dereliction of duty in the 2008 melamine-tainted milk powder case. Sanlu, a major dairy firm in China, had sold a milk powder product that was adulterated with melamine. Six infants died and some 54,000 babies were hospitalized. In the aftermath of this tragedy, government inspections revealed that similar problems existed in products from 21 other companies, fueling public outrage across the country.

With such little faith in government, one wonders why the Chinese people would trust the government’s new social credit system. A plethora of explanations may be forthcoming but two reasons stand out. First, the Chinese people have a natural proclivity to apportion blame to local governments when news of corruption breaks out. The Chinese tend to believe that individual officials at the local level are accountable for corruption scandals. They rarely, if ever, blame the central government. Moreover, a nearly five-thousand-year history of non-democratic state governance has inculcated a particular cultural stance towards government policies. Confucian tenets have deeply influenced the Chinese people’s instinct to respect authority and obey the rules imposed by a hierarchy. In short, the Chinese are inclined to submit to, rather than challenge the authority.

According to Xinhua News, the social credit system was launched in the Yangtze River Delta region (i.e. Shanghai, Jiangsu, Anhui and Zhejiang provinces).8 However, newspapers from different regions indicate that every municipal and provincial government has started to establish the social credit system at the local level.

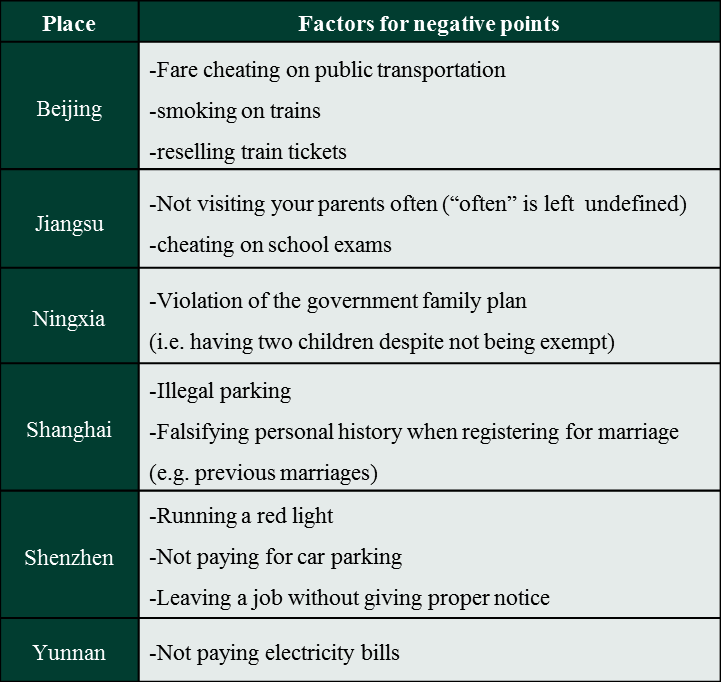

These are some examples of the type of behavior that would earn a citizen negative points in the social credit system.

* The factors listed above are far from being a complete list9

Measures and factors differ slightly across regions and localities. Some local governments are setting up their own criteria for the social credit system. Some have even created their own website, where a citizen can search information on their social credit. Most local governments established the social credit system by collecting information on corporate companies. Individuals in certain fields such as doctors, teachers, lawyers, accountants, and professional tour guides will face more intense and dedicated scrutiny because the public has long been suspicious about the standards and qualifications that these license-based professions have received from the government10.

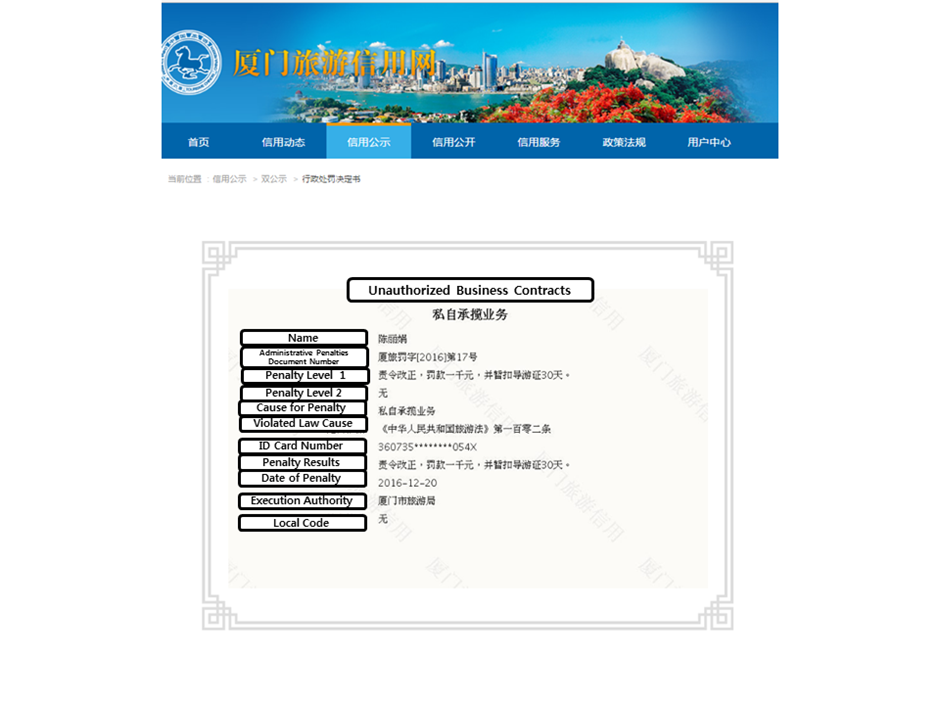

Not content with reading about the new social credit system, I decided to explore several websites related to the social credit system to understand its genesis. I researched the Travel Credit Website of Xiamen, a sub-provincial city in Fujian province: http://credit.xmtravel.gov.cn:10345/credit_tour/index.html. This website provides credit information for the tourism industry. One can search for travel agencies, hotels, and personal tour guides by entering the name, registration number, or the unified social credit number. For instance, I entered the name, Gangzhong Travel Agency (港中旅) and the following page showed up.

Information including the unified social credit number, registration number, the name of the legal representative, contact number, and address are displayed. Most importantly, this website differentiates between “good” and “warning” information on the behavior of citizens.

I clicked on the public announcement page on http://credit.xmtravel.gov.cn:10345/credit_tour/publicity/xygs-main.html. I found a list of companies and individuals in violation of the laws and policies, and those who have been punished. When I clicked on one entry, I was able to see the name, the case number, cause of violation, the date, the punishment, and the ID number (the partly blurred number, ostensibly to protect privacy, was rather ironic.)

I was able to find multiple websites similar to this one in different cities and provinces across China. It is apparent that the Chinese central government has yet to work out the details of the final integration of local information into one singular centralized system.

I called CreditChina.gov, a website that unifies several government departments, including the State Administration of Taxation, Supreme People’s Court, NDRC and the China Securities Regulatory Commission.11 Launched in June 2015, this website has collected more than 1.13 million pieces of information on companies and individuals thus far. I asked whether the CreditChina website would be the ultimate source for the social credit system. The customer service representative was vague, avoiding a clear answer. I asked whether the information presented on the CreditChina website may overlap with local websites. Again, no good answer was forthcoming.

As I dug deeper, my findings were both intriguing yet terrifying. Eight companies, including Alibaba and Tencent, that have been approved by the NDRC to issue their own social credit rating system, had been compiling financial and legal information of all their online users. The Chinese government adds this big data information to its social credit system. The most prominent and unsettling example is Alibaba’s Sesame Credit, with some 400 million users. A Sesame Credit spokesman issued a terse statement: “financial and consumption activities of our users, and materials published on social media platforms do not affect our users’ personal Sesame Credit score.”12 Li Yingyun, Sesame’s technology director, was more expansive in his February 2015 interview: “Someone who plays video games for 10 hours a day, for example, would be considered an idle person, and someone who frequently buys diapers would be considered a responsible parent. The latter would, on balance, be more likely to have a greater sense of responsibility.” Li was being timid. Joe Tsai, Alibaba’s executive vice chairman, pulled no punches: “We want people to be aware of their online behavior having an influence on their online credit score so they know to behave themselves better.”13

In one aspect, a respectable Sesame Credit score brings additional benefits. The most popular dating website in China, Baihe, uses Sesame Credit. More and more of Baihe’s 90 million members are displaying their Sesame Credit scores in their dating profiles. With a high credit score, one can make reservations at VIP hotels and car rental agencies. A sick person can be ushered to the front of the line to obtain a hospital appointment.

In October 2015, a BBC crew conducted interviews in a trendy neighborhood in downtown Beijing about Sesame Credit. The reaction ranged from enthusiasm to resigned nonchalance. One young woman (who didn’t provide her name) gushed, “It is very convenient… We booked a hotel last night using Sesame Credit, and we didn’t need to leave cash deposit.” Another woman was effusive in her praises: “A complete credit system that all links all your behavior together like shopping and travelling would be a better way to evaluate a person’s social credit.” Another young man said, “I think it is very useful. But the assessment is not fair sometimes. For example, I love buying video games but the system gives a very low rating to that sort of purchase.”14

China’s social credit system faces formidable technical and bureaucratic challenges. How can a government manage to monitor the behavior of 1.4 billion people with one single system? I wonder if Chinese officials have thought through the problem of the vulnerability of such a system to hackers. A single centralized social credit system, which would contain all kinds of information from its citizens, would be an irresistibly lucrative target for hackers. Should these hackers succeed, they could easily access or manipulate its information. In that vein, the social credit system would be ripe for corruption. If the social credit score becomes the one and only criteria for moving up or down in society, people will find a way to exploit those individuals who are in charge of the system so that their social credit scores can be favorably altered.

But set aside the pitfalls of the system. Just imagine the type of society such a system would entail. This would be the type of control that totalitarians worldwide can only dream about. Anti-social, anti-patriotic, or “false information” comments online would be crippling for a young person’s career. A mother using her son’s student travel card by mistake may accrue negative points; running a red light, parking in a prohibited zone, and honking his horns in the rush to get home, a grandfather wanting to surprise his grandson by purchasing video games online could accrue negative points in the social credit system. A housewife forgetting to pay the utility bill on time jeopardizes the chance of her daughter gaining admissions to a prestigious university.

The social credit system should be renamed the social control system. It sets up the CCP as the ultimate moral authority of social behavior. Everything a Chinese citizen does will be monitored, evaluated and graded. This, in turn, will affect all and every aspects of one’s life such as getting loans, jobs, and overseas travel permits. And the fact that companies like Alibaba are providing users’ information to the government is deeply disturbing.

Conclusion

Reflecting back on that taxi ride in Shanghai, I found it odd that a taxi driver would have to be penalized for honking his horn when needed. But therein lies the rub. It has nothing to do with curtailing honking. It has everything to do with the Chinese government’s desire to know everything about its citizens and foster self-censorship for the ultimate purpose of controlling the behavior of the people. With this system, the government can rate and rank people; by doing so, the government can gradually but ultimately compel people to behave exactly the way the government wants them to be (i.e. “patriotic”).

Whether China’s social credit system will actually work, or how extensively it can be implemented, remains to be seen. But the genesis of and philosophy behind the social credit system underscores the mindset of the Chinese Communist leaders. In fact, their method is quite antediluvian – set a goal and use whatever methods to achieve the goal. It is hard to imagine if there are any concerns or discussions in the central government about any moral or legal implications, and unintended or counterproductive “side effects”. Rather than educating drivers on the advantages of desisting from honking and provide incentives to reduce noise pollution, the Chinese government reflexively turns to an authoritarian, unilateral, and top-down approach. After all, the Chinese leaders view themselves as managers of unruly citizens who must be controlled. And the truth is the Chinese people seem to be okay with that. The “actual” objective is to monitor citizens in toto. The Chinese central government’s social credit system is geared to reward those who fall in line with the CCP “way” and act suitably, and punish those who stray. If this system becomes universal, the Chinese government would be able to exercise total control over each and every Chinese citizen. It is social control at its best.

When I first learned of China’s social credit system, my first thought was – “what would my social credit score look like after having lived abroad for over 10 years and after clicking so many “likes” on news links on Facebook critical about the smog problem in China?” I suspect my social credit score would be in the neighborhood of minus 200. Meanwhile, walking the streets of Seoul, carefree and unencumbered, I cannot help but wonder – what if the South Korean government carried out a similar program?

* This study was supervised by Dr. Kim Jinwoo, Director, Office of Strategy and Analysis.

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

-

1.

George Orwell, 1984 (London: Penguin Modern Classics, Paperback, 2004), p.240

-

2.

“关于印发《上海市公安局、上海市环境保护局关于禁止机动车和非机动车违法鸣喇叭的通告》的通知”, May 10, 2007 http://www.shanghai.gov.cn/shanghai/node22848/node22926/node22928/userobject21ai344575.html / Accessed on January 3, 2017

-

3.

“Planning Outline for the Construction of a Social Credit System (2014-2020)”, April 25, 2015, https://chinacopyrightandmedia.wordpress.com/2014/06/14/planning-outline-for-the-construction-of-a-social-credit-system-2014-2020/ Accessed on January 10, 2017

-

4.

“China outlines its first social credit system”, Xinhuanet, June 27, 2014 http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2014-06/27/c_133443776.htm Accessed on January 20, 2017

-

5.

“4.9m people with poor credit record barred from taking planes”, Global Times, November 2, 2016 http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1015549.shtml Accessed on January 25, 2017

-

6.

FICO Score is a measure of consumer credit risk which has become a fixture of consumer lending in the United States.

-

7.

Hatton, Celia “China ‘social credit’: Beijing sets up huge system”, BBC News, October 26, 2015 http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-34592186 Accessed on February 2, 2017

-

8.

“China Focus: China plans social credit system pilot”, Xinhua News, January 1, 2017 http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-01/01/c_135948174.htm Accessed on January 1, 2017

-

9.

“铁路部门宣布将乘火车7种‘失信行为’纳入信用记录”, Credit Beijing Website, January 24, 2017 http://www.creditbj.gov.cn/801/xybj/infoLink/2017-01-24/19542.html Accessed on January 24, 2017

“深圳:停车不缴费可被视为失信行为”, 全国个人诚信公共服务平台, November 2, 2016, http://www.11-22.org/Info/View.Asp?id=5395 Accessed on January 24, 2017

“与征信挂钩让‘常回家看看’落地”, Sina News, April 7, 2016, http://news.sina.com.cn/o/2016-04-07/doc-ifxrckae7604263.shtml Accessed on January 24, 2017

“上海1月起骗婚等婚登失信行为将受惩戒”, China News, December 27, 2016, http://www.chinanews.com/gn/2016/12-27/8106148.shtml Accessed on January 24, 2017

“江苏省教育系统失信惩戒办法(试行)”, Trust Jiangsu, February 8. 2017, http://www.jscredit.gov.cn/cxjsPub_articleDetail.do?channelid=zcfg&contentId=2e944881066847beacbf398d85d22f8b Accessed on February 8, 2017

Qiu Xi, “宁夏:生育情况纳入社会信用体系,重点查处政策外多孩生育”, The Paper, November 3, 2016, http://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_1554159 Accessed on February 1, 2017

“‘闪辞’等个人职场失信行为将被记录在案”, 深圳劳动法律师网, http://www.szfulvshi.com/lswj/1628.html Accessed on February 22, 2017

“昆明:12月20日起用电客户3种失信行为将纳入征信记录”, 云南网,November 29, 2016, http://society.yunnan.cn/html/2016-11/29/content_4635315.htm -

10.

“医生教师记者导游将建诚信档案”, The Beijing News, May 13, 2015 http://www.bjnews.com.cn/feature/2015/05/13/363253.html Accessed on January 3, 2017

-

11.

“China launches credit score website”, The State Council, The People’s Republic of China, June 2, 2015, http://english.gov.cn/news/top_news/2015/06/02/content_281475119495270.htm Accessed on January 3, 2017

-

12.

Hatton, Celia “China ‘social credit’: Beijing sets up huge system”, BBC News, October 26, 2015 http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-34592186 Accessed on February 2, 2017

-

13.

Cendrowski, Scott, “Here are the companies that could join China’s Orwellian behavior grading scheme” , November 29, 2016 http://venturebeat.com/2016/11/29/here-are-the-companies-that-could-join-chinas-orwellian-behavior-grading-scheme/ Accessed on February 10, 2017

-

14.

Hatton, Celia “China ‘social credit’: Beijing sets up huge system”, BBC News, October 26, 2015 http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-34592186 Accessed on February 2, 2017

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter