Introduction

Broadening strategic competition between China and the United States has put greater pressure on South Korea to make choices between the United States as South Korea’s primary security guarantor and China as South Korea’s largest economic partner. How South Korea navigates the rising Sino-U.S. rivalry will have implications for the future of Sino-ROK relations as well as for the durability of the U.S.-ROK alliance.

Historically, South Korea has pursued a strategy of choice avoidance in management of relations between the United States and China, but China’s economic retaliation following South Korea’s 2016 decision to accept deployment of a U.S. mid-range missile defense system to counter North Korea’s ongoing missile development has soured South Korean public perceptions of China. In addition, the ongoing Sino-U.S. trade war and deepening negative perceptions of China as an emerging adversary, as reflected in the latest U.S. National Security Strategy, have generated U.S. pressure on South Korea to make the choice to side with the United States.

As South Korea faces increasing pressure to choose between China and the United States, South Korean public attitudes toward China and the United States serve as an indicator of how South Korea will likely make decisions in an increasingly complex strategic environment.

The Asan survey conducted in July 2019 focuses on South Korean attitudes toward China and the United States.1 The poll demonstrates that South Korean attitudes toward the United States remain considerably more positive than South Korean attitudes toward China. Although South Koreans continue to prefer a strategy of cooperation over a strategy of confrontation toward China, South Korean public trust in the United States is decisively stronger than trust in China.

Favorability

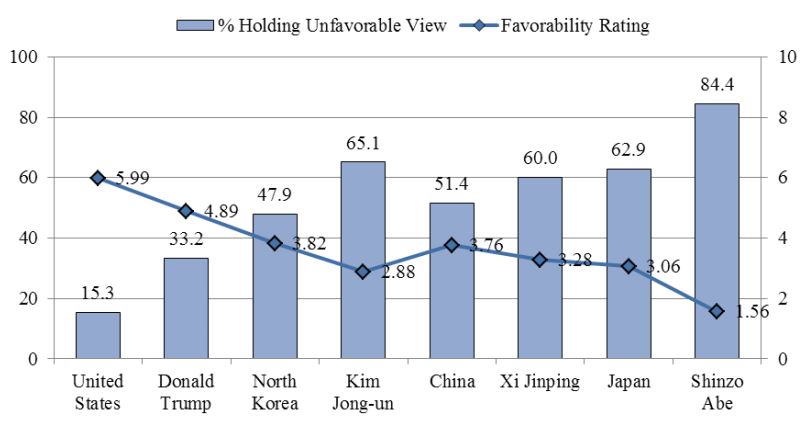

Despite the South Korean government’s unclear position with respect to its relations with China and the United States, the Korean public continues to lean steadfastly toward the United States. The average favorability of China (3.76) lags behind that of the United States (5.99) and North Korea (3.82). It appears that despite many changes in the region, relations between South Korea and its main security and economic partners have remained unchanged. This is also reflected in country favorability trends over time. While we see an uptick in South Korean favorability of North Korea as of 2018, favorability ratings for China remains constant (See Figure 1).

According to the survey results, 51.4% of South Koreans express an “unfavorable” view of China compared to nearly 62.9% for Japan, 47.9% for North Korea, and 15.3% for the United States (See Figure 1). Over the half of South Koreans holds unfavorable views of close neighbors (North Korea, China, and Japan).

The South Korean public holds similar opinions of the leaders of these countries. The survey data shows that South Koreans have a more favorable view of China’s President Xi Jinping (3.28) than North Korea’s leader Kim Jong-un (2.88) and Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe (1.56), but the U.S. President Donald J. Trump (4.89) is the most favored leader. The average favorability of country leaders was about five points, which can be interpreted as neutral. Unfavorable views of China’s President Xi Jinping reached 60 %, higher than that of Kim and lower than that of Abe. Interestingly, Xi’s favorability is lower among younger respondents (20s=2.77, 30s=2.89) than older ones (50s=3.66, 60+=3.61). China’s favorability was also higher among older respondents (50s=3.84, 60+=4.04) than younger ones (20s=3.54, 30s=3.54).

Figure 1. Favorability2 (left: %, right: 0~10 point)

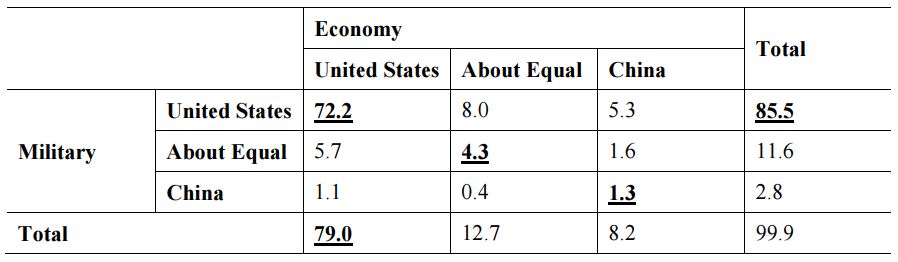

Power Rivalry Between the United States and China

China’s GDP is projected to overtake that of the United States within the next ten years, and its current military spending, at about $200 billion (2% of GDP), is second largest in the world, behind the United States.3 When asked to evaluate which country has a stronger economy or military, the South Korean public saw the United States as having the edge in both economic and military power. 79% of respondents say the United States has a stronger economy than China (8.1%; about equal 12.6%). An even larger majority (85.5%) views the United States as having a stronger military (China 2.8%; about equal 11.5%). Results were consistent across all age groups and political leanings.

Table 1. South Korean Views on the Power Rivalry Between the United States and China4 (%)

The cross-tabulation derived from the two questions shows that 72.2% of respondents see the United States as having both a stronger economy and military (See Table 1). In contrast, only 1.3% sees China as having a stronger economy and military and only 4.3% see the economy and military of the United States and China as about equal.

Impact of Bilateral Relations on National Security

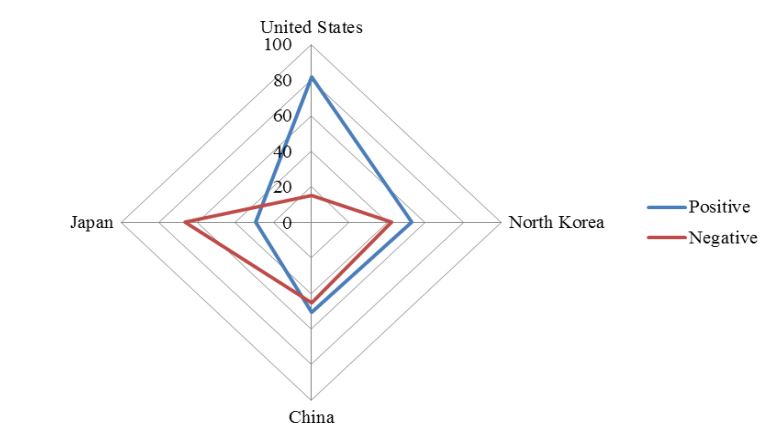

The South Korean public’s assessment of the relative positioning of the United States and China appears to inform their opinions about the impact of bilateral relations on South Korea’s national security. When asked about the impact of bilateral relations with neighboring countries, 81.6% of respondents see U.S.-ROK relations as having a positive impact and only 15.2% responded in the negative (See Figure 2). Opinions are more split on Sino-ROK relations (positive 50.5%, negative 45.2%). The public has similar views on North Korea (positive 53%, negative 42.5%). In contrast, the respondents saw Japan-ROK relations as being on net more negative for South Korea (positive 29.3%, negative 66.4%), an apparent result of heightened tensions between South Korea and Japan over historic grievances.

Figure 2. Influence of Bilateral Relations and South Korean National Security5 (%)

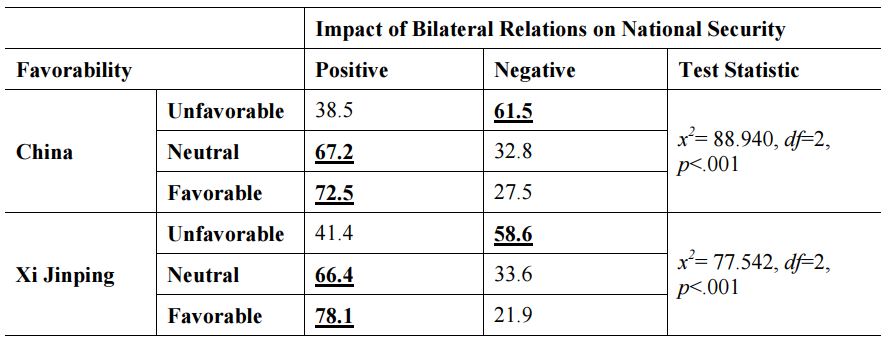

On Sino-ROK relations, younger respondents appear to hold more negative views (20s=54.8%, 30s=48.2%) than older respondents (50s=42.2%, 60+=43.1%). Survey findings correspond with South Korean views about China and Xi Jinping (See Table 2). Respondents with a more favorable view of China and President Xi hold a more positive view of bilateral relations (favorable view; China 72.5%, Xi 78.1%), while those with a less favorable view of China and Xi are more likely to have a negative view of the overall impact of bilateral relations (unfavorable view; China 61.5%, Xi 58.6%).

Table 2. South Korean Favorability and Bilateral Relations on National Security6 (%)

Trade War

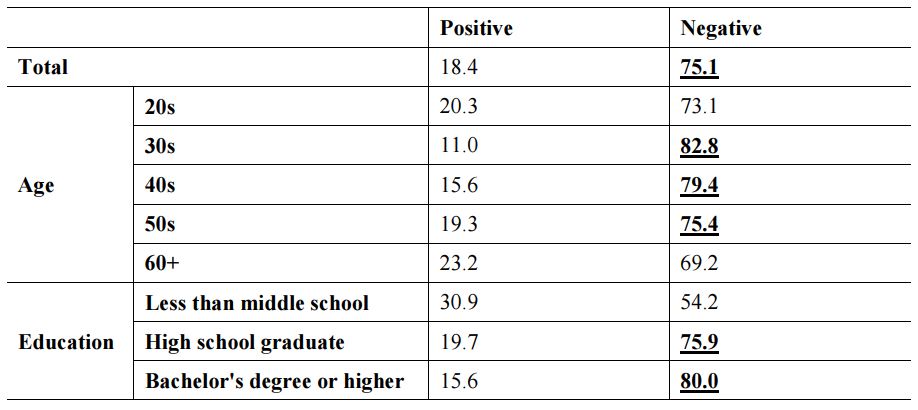

South Koreans remain concerned by the potential impact of the ongoing trade dispute between the United States and China. Over 75% of respondents think the U.S.-China trade war will negatively impact South Korea’s national security (See Table 3). Consistent with their role as the most economically active segments of the overall population, middle-aged and more educated respondents expressed the most pessimism (30s=82.8%, 40s=79.4%, and 50s=75.4%).

Table 3. U.S.-China Trade War and South Korean National Security7 (%)

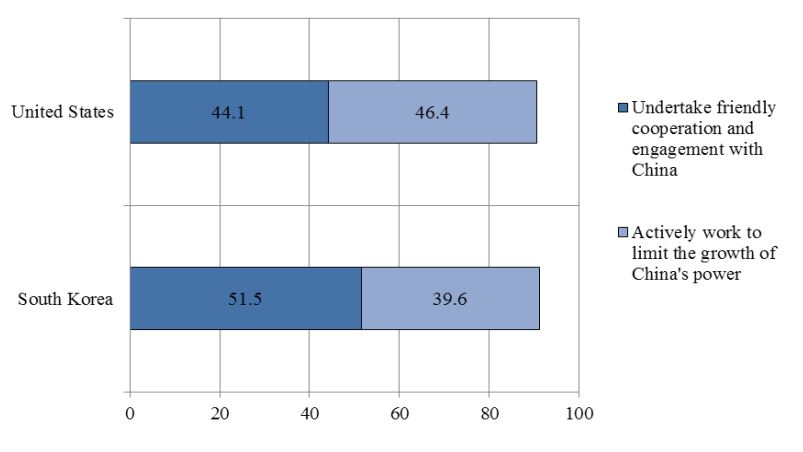

Managing China

The South Korean public holds a range of views about how best to manage relations with China (See Figure 3). When asked about the best way to deal with China’s rise, 51.5% of respondents stated that South Korea should undertake a more amicable approach in its engagement with Beijing. About 40% of respondents believe South Korea should actively work to limit China’s rise. In comparison, when asked what they thought the United States should do about China, 44.1% of respondents say the United States should take a softer approach in managing China’s rise and 46.4% say the United States should actively work to limit the growth of China’s power.

South Koreans appear split over how the United States should handle strategic competition with China, but a majority prefers that South Korea avoid direct confrontation with China. Responses were noticeably different across generations, with younger South Koreans preferring greater checks and balances against China (South Korea 20s=52.3%, 30s=49.1%; United States 20s=59.2%, 30s=55.7%) than older respondents.

Figure 3. Managing the Rise of China8 (%)

Future Partner

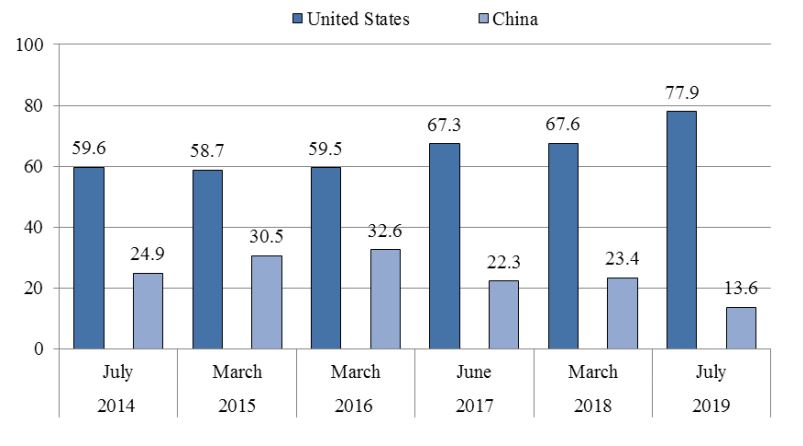

South Korean views of China and the United States have evolved over the past several years. According to the survey data, less than 14% of South Koreans perceive China as a reliable future partner (See Figure 4). In comparison, 77.9% of respondents state that they see the United States as a reliable future partner. This is a marked change from 2016, when about 60% of South Koreans saw the United States as a reliable future partner and nearly 33% saw China as South Korea’s future partner.

Three main factors account for this change. First, Sino-ROK bilateral relations sharply declined after South Korea reached an agreement with the United States to deploy the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) capability in July 2016. China responded by accusing South Korea of working with the United States to threaten China’s strategic interests. Subsequently, there was a nationwide boycott against South Korean goods and services in China. Bilateral relations between South Korea and China have yet to recover.

Second, during Trump’s presidency, the U.S. role in Korean Peninsula affairs and North Korean denuclearization has grown. So far, Trump has met with Kim three times in an attempt to negotiate a denuclearization deal with North Korea, a marked change from the escalation in 2017 that coincides with the policy preferences of the current South Korean administration.

Finally, the U.S.-ROK bilateral relations have progressed significantly over the past two years. The United States and South Korea successfully renegotiated the Korea-U.S. Free Trade Agreement and agreed to complete implementation of revised wartime operational control arrangements that will signal greater South Korean responsibility for its own security by the end of South Korean President Moon’s term. Though the two countries have yet to address a number of outstanding issues, including the new Special Measures Agreement dividing the costs of supporting U.S. troop presence in South Korea between the two countries, the South Korean public has little to complain about as far as the U.S.-ROK alliance is concerned.

Figure 4. South Korea’s Future Partner9 (%)

Conclusion

Overall, the South Korean public shows a strong preference for continued close reliance on the United States as a security buffer and hedge against growing Chinese regional influence. South Korean favorability toward the United States continues to outpace favorability toward any of its immediate neighbors, including China. Chinese economic retaliation for South Korea’s decision to allow the deployment of THAAD appears to have had an enduring psychological impact on South Korean perceptions of the United States as a preferred security partner and of China as an uncertain neighbor. China’s relative power vis-à-vis the United States continues to grow, and the trajectory of China’s economic power is predicted to surpass that of the United States. However, South Korean views of which country will be the most powerful economic player within the next decade have shifted from several years ago, with more South Koreans now expecting the United States to retain its role as a leading economic partner. This South Korean expectation for the future appears to reflect South Korean hopes and fears regarding the Sino-U.S. relationship, rather than an assessment based on empirical trends.

South Koreans face a growing realization that China will continue to rise, checked by concerns about the implications for South Korea’s national interest. Increasingly, China’s economic power appears to be less of an opportunity for South Korean to take advantage of to secure its own prosperity and more of a risk factor that requires a hedge. South Korean favorability and positive preferences for continued engagement with its American allies suggest that the alliance is valued because it offers a hedge against the perceived risks associated with China’s regional expansion of power and influence.

Survey Methodology

Sample Size: 1,005 respondents over the age of 19

Margin of Error: ±3.1% at the 95% confidence level

Survey Method: Random Digit Dialing (RDD) for mobile and landline phones using Computer Assisted Telephone Interview (CATI)

Period: See footnotes

Organization: Research & Research

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 1. This data was also used in a comparative study of American and South Korean public attitudes toward China in cooperation with the latest Chicago Council on Global Affairs survey on American public opinion and foreign policy released in October 2019 (https://www.thechicagocouncil.org/publication/cooperation-and-hedging-comparing-us-and-south-korean-views-china).

- 2. Asan Poll (July. 9~10, 2019).

- 3. See “China Could Outrun the U.S. Next Year or Never,” Bloomberg, March 9, 2019; W Chen; X Chen; CT Hsieh; and Z Song. “A Forensic Examination of China’s National Accounts,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. BPEA Conference Draft, March 7-8, 2019; J O’Neil and A Stupnytska, 2009, “The Long-Term Outlook for the BRICs and N-11 Post Crisis,” Global Economics Paper No. 192, Goldman Sachs. December 4, 2009; “SIPRI Military Expenditure Database; “China’s Military Power Nears ‘Parity’ with the West, Report Says,” Popular Mechanics, February 16, 2017.

- 4. Asan Poll (July. 9~10, 2019). In an analysis, the responses including “Don’t know” and “Refused to answer” were excluded as missing values.

- 5. Asan Poll (July. 9~10, 2019).

- 6. Asan Poll (July. 9~10, 2019). In an analysis, the responses including “Don’t know” and “Refused to answer” were excluded as missing values.

- 7. Asan Poll (July. 9~10, 2019).

- 8. Asan Poll (July. 9~10, 2019).

- 9. Asan Poll (July 4~6, 2014; Mar 11~12, 2015; Mar 22~24, 2016; June 1~3, 2017; Mar 21~22 2018; July. 9~10, 2019).

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter