The last two decades have seen a marked increase in defence spending by Southeast Asian countries. While many have attributed this to conflicts with China in the South China Sea and the security threats posed by China’s rise, it is more likely to be a normalisation of military capabilities or the acquisition of adequate capabilities for self-defence. Under the protection of the Cold War, Southeast Asian countries diverted resources from defence to economic growth, and their militaries, which were more concerned with preparing for domestic political instability or intervening in domestic politics than with external threats, did not see much need to upgrade their weapons systems. This situation changed with the end of the Cold War and the economic growth of Southeast Asian countries. They need to have defence capabilities commensurate with their size, and they need to have a minimum response capability in the event of a territorial dispute with China. For these reasons, Southeast Asian countries are likely to continue investing in their militaries and strengthen their defences for some time.

Trends in defence spending and military build-up in Southeast Asia since 2000

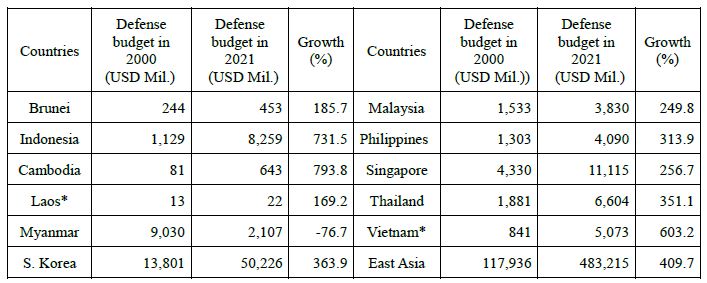

Since 2000, there has been a growing interest in strengthening the military capabilities of Southeast Asian countries. In particular, the trend of military build-up in Southeast Asia is of particular interest since the US-China strategic competition has been the most intense since it began.1 From 2000 to 2021, defence spending in most Southeast Asian countries increased significantly (See Appendix 1). During this period, East Asia as a whole and South Korea in particular increased their defence spending by 4.1 and 3.6 times, respectively, while Indonesia increased by 7.3 times, Cambodia by 7.9 times, and Vietnam by six times. Vietnam’s defence spending, which ranked seventh in Southeast Asia in 2010, rose to fourth in Southeast Asia in 2021. Singapore’s increase in defence spending was only 2.6 times, but it was already a big defence spender, and by 2021, it was the only Southeast Asian country to spend more than $10 billion on defence.2

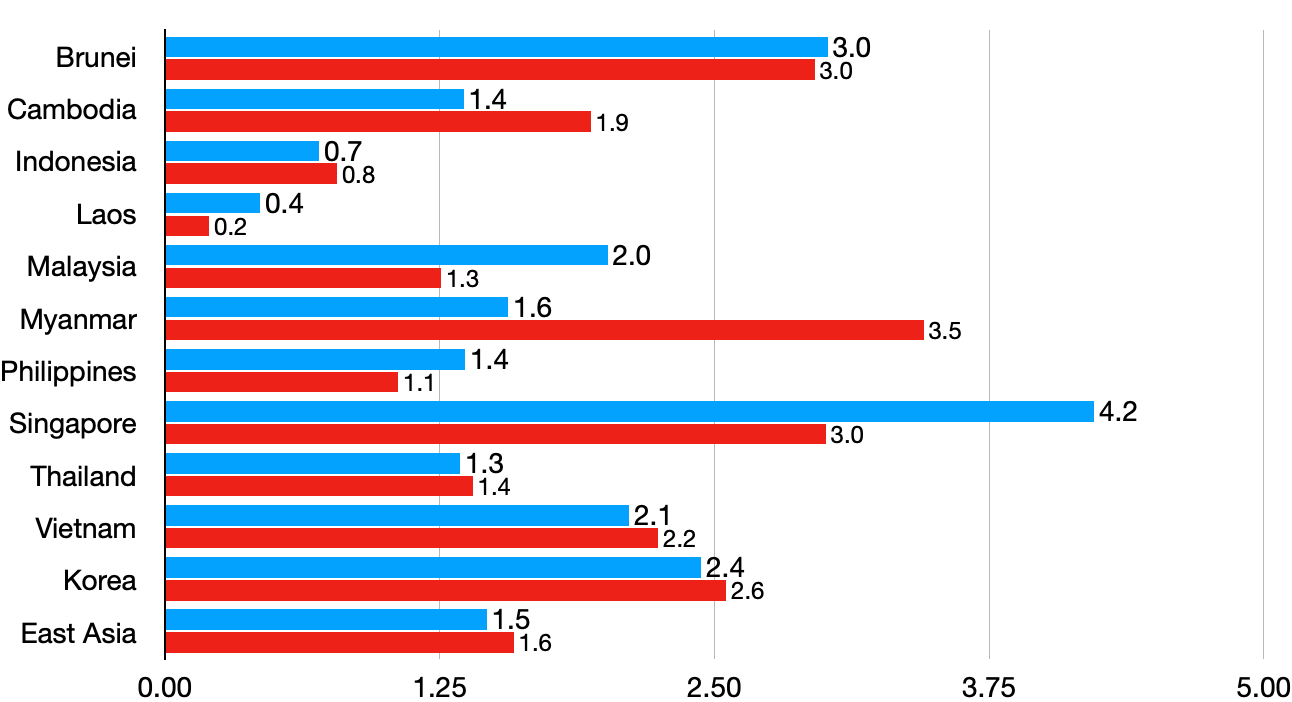

Just as significant as the absolute increase in defence spending is the increase in defence spending as a percentage of GDP (see Appendix 2). From 2000 to 2010, Malaysia (2.0%), Vietnam (2.1%), Brunei (3.0%), and Singapore (4.2%) significantly outpaced East Asia’s overall GDP-to-defence ratio (1.5%). Even South Korea, which faces constant threats from North Korea, was at just 2.4 percent. This trend continues in the ten years from 2011 to 2021. Singapore (3.0%) and Brunei (3.0%) still exceed the East Asian average (1.6%) and South Korea’s (2.6%) defence spending as a percentage of GDP. Vietnam has also increased its defence spending as a percentage of GDP, spending 2.24% of GDP on defence from 2011 to 2021, a modest increase from the decade prior.3

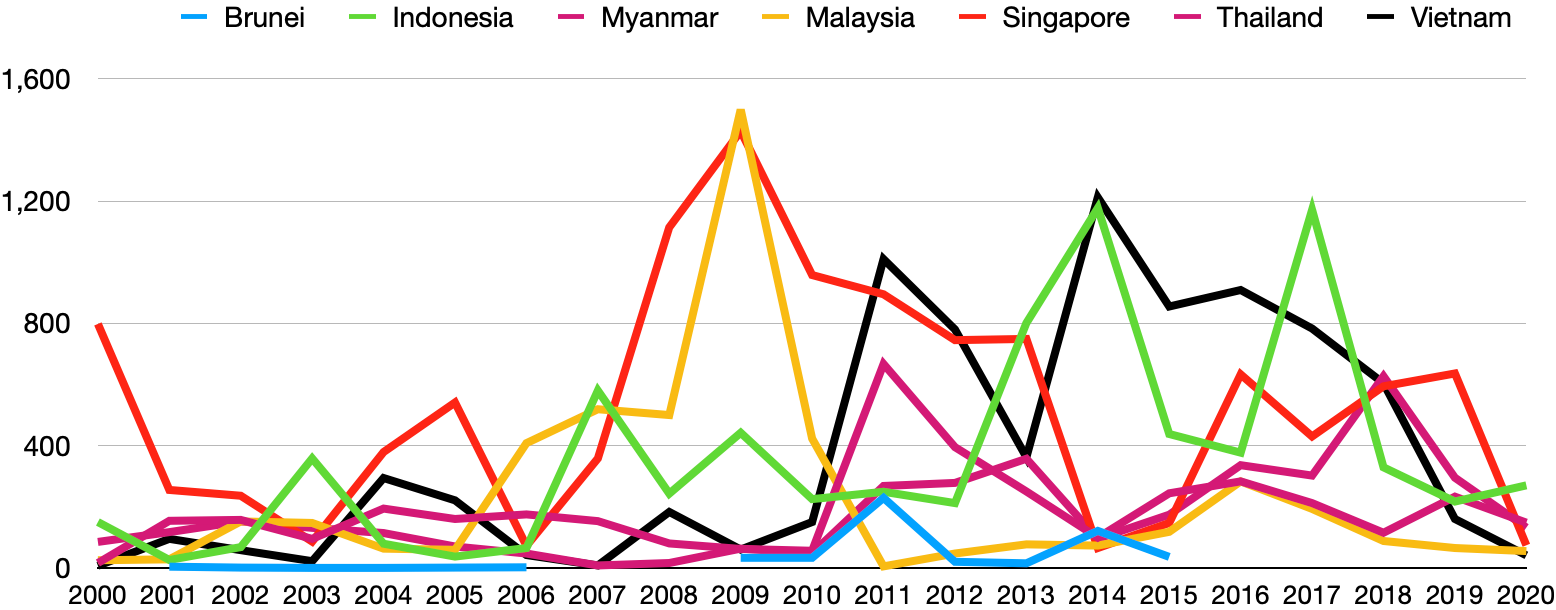

Southeast Asia’s growing military might is also reflected in its arms imports. The level of defence technology in Southeast Asian countries is not very high, and most of their major weapons are imported. Since the 2000s, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Vietnam have led Southeast Asia’s arms imports in staggered order.4 Singapore’s arms purchases have been relatively steady over the period. Malaysia spent heavily on arms imports at one point around 2010, while Indonesia spent heavily in the mid-2010s after the presidency of Joko Widodo began. Vietnam saw a surge in arms purchases in the early 2010s, coinciding with the emergence of the US pivot policy and increased strategic cooperation between the US and Vietnam.

As interesting as the absolute value of arms imports is the question of which arms exporters dominate the Southeast Asian market, with no single country being dominant. According to one report citing data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), the arms shipments of Southeast Asian countries from 2000 to 2019 show that Russia tops the list with $10 billion in sales, followed by the United States with about $7.9 billion, France with $3.5 billion, Germany with $2.8 billion, China with $2.6 billion, South Korea with $2.1 billion, and the United Kingdom with $1.3 billion worth of weapons sold to Southeast Asia.5 While Russia tops the list, it is not overwhelmingly skewed towards any one country.

Is Southeast Asia seeking an arms race with China?

The China threat has been a frequent theme in Southeast Asian states’ armament build-ups over the past two decades, especially since the 2010s.6 While it is true that concerns about China’s potential security threats have grown, claims that Southeast Asian states are modernising and building up their militaries only to counter China and that this is leading to an arms race with Beijing are somewhat exaggerated. Colin Gray sees the conditions for an arms race as 1) the existence of an antagonistic adversary, 2) the organisation of military forces in such a way as to counter the adversary, 3) the qualitative and quantitative expansion of military power, and 4) the resulting rapid expansion and qualitative improvement of military capabilities.7 Southeast Asian states’ relations with China, and Southeast Asian states’ military build-up, do not meet these conditions. Southeast Asia and China do not appear to be antagonistic adversaries, and as we will see below, Southeast Asia’s military build-up has not been an effective deterrent to China, nor has Southeast Asia’s military expansion kept pace with China’s military expansion.

The first thing that may come to mind regarding Chinese security threats to Southeast Asian states is territorial disputes in the South China Sea. China’s naval and air power are likely to be the most important military forces in the event of encroachment into the exclusive economic zones and territorial waters of Southeast Asian countries, territorial disputes in the South China Sea, and maritime threats. However, the combined naval and air power of the ten Southeast Asian countries is insufficient to match China’s. They are vastly outnumbered not only in terms of troops but also in ships and aircraft. The combined total defence spending of the ten ASEAN countries is only one-seventh of China’s (see Appendix 3). Under these circumstances, it is unconvincing to expect Southeast Asian countries to rapidly increase their armaments to prepare for a Chinese security threat. Rather, drawing in the United States to balance China militarily is a more desirable strategy for Southeast Asian states in terms of cost and effectiveness.

However, Southeast Asian countries cannot afford to sit idly by as China uses its overwhelming naval power and Chinese-backed maritime militias in the South China Sea to effectively occupy South China Sea islands controlled by Southeast Asian countries or as Chinese fishing boats invade Southeast Asian countries’ exclusive economic zones. They must demonstrate a willingness to defend their sovereignty and territorial waters against China with “minimum essential force” or “minimum credible deterrence”.8 In this sense, Southeast Asia’s military build-up can be seen as an attempt to ensure that they have the minimum military capability to resist or protest China’s military activities meaningfully.

Military’s political intervention has stalled Southeast Asia’s military advancement

To properly explain Southeast Asia’s increased defence spending and military build-up over the past two decades, it is necessary to look at the historical and structural background. Simply put, the nature of Southeast Asian militaries, and the historical experience of Southeast Asian countries, has long retarded the modernisation of their militaries. Southeast Asia’s military expansion since the 2000s is not only a response to specific threats but also a reaction to structural delays in modernisation. At first glance, the argument that military modernisation in Southeast Asia has stalled does not seem very convincing. Several Southeast Asian countries have powerful militaries. If they were stronger, they would have made some effort to upgrade their military equipment and weapon systems, even if it was not economically feasible, and there would not have been a sudden rush to modernise.

The history and experience of Southeast Asian militaries have shown a different trajectory to this general reasoning. The armies of Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, and Myanmar are among the most powerful in Southeast Asia. Not only are they large, but they are also powerful entities with significant domestic influence. However, having a strong military is not the same as having strong military power. In the Southeast Asian context, the former means having significant domestic influence due to political participation, not having strong military power due to military modernisation. In other words, in Southeast Asia, militaries do not follow the usual civil-military relations formula of increasing defence spending and expanding military capabilities for collective interests – it is the internal interests that bind them together.

The Indonesian military functioned as a security instrument of the Suharto-era regime beginning in 1966. It has legitimised its involvement in domestic politics through the dual function (Dwi Fungsi) clause in the constitution, which gives it responsibility for national security as well as social development. In Myanmar, the military seized political power in a coup d’état in 1962 during an ethnic conflict between the Burmese and ethnic minorities and maintained military rule for 53 years, until 2015. Thailand’s military has seized political power in about 20 military coups since the country adopted a constitutional monarchy in 1932. More than half of around 50 cabinets formed since 1932 have been military-dominated.9 Vietnam’s military also gained domestic legitimacy based on its victories in the U.S.-Vietnam War and the Third Indochina Peninsula War with China. Today, it is the most robust foundation for the Vietnamese Communist Party’s hold on power.

In addition, neither the military regime, the suppression of domestic opposition to maintain the authoritarian regime, nor the suppression of democratic demands, require advanced weaponry. Therefore, despite the political influence of the powerful military, it has shown minimal interest in modernising its equipment and weaponry, or at least maintaining equipment and weaponry commensurate with the size of the state and its economy. In addition, the defence budget is likely to have been diverted for other purposes than increasing power, due to corruption. This has left the post-Cold War, post-democratisation Southeast Asian militaries with a poorly equipped arsenal.

The Cold War security umbrella and the delayed military build up

The relative absence of conflict in the region and the security umbrella provided by the United States, coupled with the aforementioned variable of domestically oriented militaries, further slowed the modernisation of Southeast Asian militaries. Most Southeast Asian countries were incorporated into the Cold War order with their independence. Singapore, the Philippines, Thailand, and Malaysia were early members of the US-led bloc. The Philippines served as the U.S. forward base for Southeast Asia at sea, centred on Subic Bay Naval Base and Clark Air Force Base. The United States provided the Philippines with supplies and training.10 Thailand was also a U.S. ally, serving as a rear-guard base during the Vietnam War, providing air bases for U.S. military operations in the Indochina Peninsula, and receiving training and supplies from the United States.11 Britain, which had colonial rule in the Malay Peninsula, stationed troops and provided support and training to the Malaysian military until 1960 to manage the communist threat in the region.12 At Malaysia’s independence in 1957, the UK and Malaysia signed the Anglo-Malayan Defence Agreement (AMDA), under which Malaysia received security-related assistance from the UK.

During the Cold War, with communist threats in Southeast Asia, including Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, China, and the Soviet Union, the United States and other Western countries provided the military support and security that non-communist Southeast Asian countries needed. As individual states in the anti-communist bloc received security guarantees and security public goods from the United States, Britain, and other Western countries, there was no strong incentive for them to devote resources to the development of their own defence and military capabilities. Southeast Asian countries were able to invest their resources in economic growth to ensure domestic stability and political support. Moreover, under the Cold War strategy, the American market was wide open to these anti-communist Southeast Asian countries. The five ASEAN countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, and Singapore), which diverted resources from the military and military modernisation to the economy, experienced rapid economic growth during this period and rose to the ranks of middle-income or developed countries by the 1990s.

The absence of regional military conflict, coupled with this external security, has made Southeast Asian states less interested in military build-up. One of the reasons for the creation of ASEAN was regional conflict. Since its inception, ASEAN has considered the prevention of regional conflicts and the improvement of trust between countries to be its most significant achievements.13 Of course, there was the context of the Vietnam War, but the Vietnam War can be considered an extra-ASEAN event for ASEAN. In both the First and Third Indochina Wars, Vietnam was not a member of ASEAN at the time. The countries that were in conflict with Vietnam were also forces outside of ASEAN, so these three Indochina wars were technically fought by non-ASEAN countries in Southeast Asia. At least since the inclusion of Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, and Myanmar in the group, there has been no intra-regional military conflict between ASEAN members.

Drivers of Arms Expansion: Growth, Post-Cold War, and the Changing Nature of the Military

After the end of the Cold War, the militaries of Southeast Asian countries faced a backward reality. One-third of the Indonesian Navy’s ships are estimated to be too old to operate at sea. Among the Indonesian Air Force’s fighter jets, the F-5 is already 34 years old, while the Hawk 53 and T-34 trainers are 32 and 33 years old, respectively. The 737 Maritime Patrol Aircraft (MPA), a modified Boeing 737, is also 32 years old. The situation is even worse for transport aircraft, with C-130s at 40 years old, F-27s at 38 years old, and KC-130B tankers at 53 years old.14 The last operational fighter jet in the Philippine Air Force was also retired in 2005, leaving it without a single operational fighter.15 The Vietnamese, Laotian, and Philippine militaries’ equipment averages more than 35 years old.16

Of course, Southeast Asian nations deferred military build-up and focused on economic growth, which led to rapid economic growth. Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and others experienced their best years of economic growth in the 1990s. After overcoming the 1997-98 financial crisis, they set out to make up for their defence deficits in the 2000s. In 2012, Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono said of the country’s rapid military build-up at the time: “The answer is very simple: What Indonesia has is far behind that which our neighbours have. We only intend to bridge that gap so we can maintain our sovereignty and peace. For 15 to 20 years, our military modernisation did not proceed as it should have because of economic reasons and other pressing priorities.”17

Added to this is the variable of the changing nature of the military in some countries in Southeast Asia. Whereas in the past, the military’s main task was to maintain authoritarian rule and suppress domestic secessionist movements, democratisation has led to a reprioritisation of the military.18 Southeast Asian militaries, which once required overwhelming numbers of troops and only basic weaponry, have begun to see external threats after democratisation, making their weapon systems and military capabilities less effective. In addition, the recent strengthening of Southeast Asian militaries has mainly centred on air and naval forces.19 According to a report by SIPRI, 52 percent of the weapons purchased by Southeast Asian countries in the five-year period from 2007 to 2011 were related to maritime operations. Furthermore, when aircraft and associated missiles and radars are included, maritime-related arms imports rise to 89 percent of total arms imports.20 As the missions of Southeast Asian militaries have shifted from domestic to external affairs, they have become more concerned with maritime issues and maritime security, especially in maritime Southeast Asian countries. This has led to modernising military forces, particularly naval and air forces.

ASEAN-Korea Defence Cooperation: Supporting Adequate Defence Capability for Peace

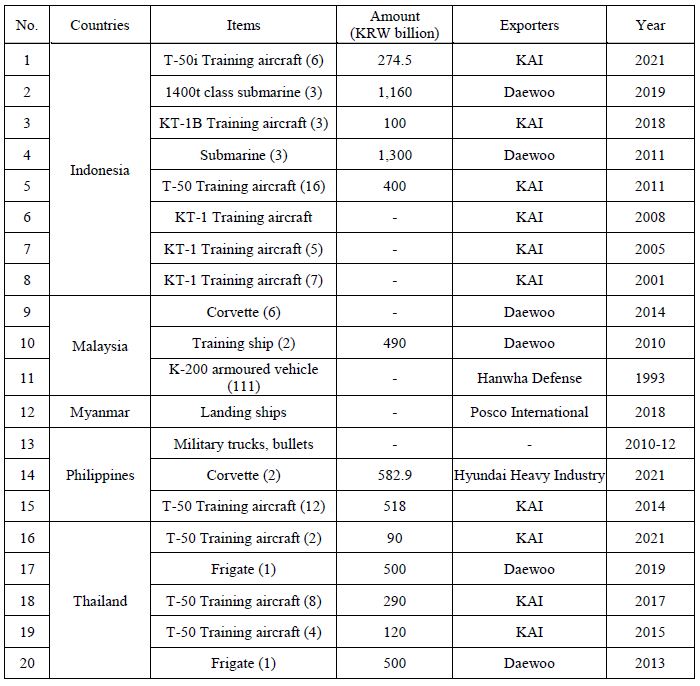

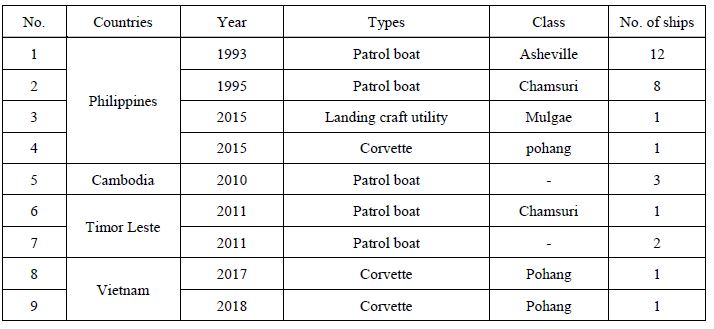

The military modernisation drive of Southeast Asian countries is also an economic opportunity for Korea, which provides the basis for further development of defence and security cooperation between Korea and Southeast Asian countries. South Korea is gaining traction in the international defence market. South Korea’s defence industry is expanding its market in European countries and Southeast Asia, including large-scale defence equipment exports to Poland after the war in Ukraine. In 2022, South Korea exported K-2 tanks, K-9 self-propelled artillery, and FA-50 light attack aircraft to Poland. In Southeast Asia, South Korea has been steadily exporting aircraft, submarines, and ships to Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand since the 2000s. Exports to Southeast Asia have been accompanied by donations of obsolete defence equipment, especially since the 2000s. South Korea has provided the Philippines, Cambodia, East Timor, and Vietnam with about 30 outdated ships since 1993 (see Appendix 4 and 5).

Political and security cooperation was an important part of the Moon administration’s New Southern Policy, which envisaged defence and defence cooperation with Southeast Asian countries. The current administration’s new ASEAN strategy, the Korea-ASEAN Solidarity Initiative (KASI), also emphasises national defence and strategic cooperation. Southeast Asian countries are also keenly interested in defence and science and technology cooperation with Korea.21 South Korea’s advanced science and technology, its status as a non-threatening power unlike the United States and China, and its neutral image and soft power have combined to make it a desirable partner for Southeast Asian countries looking to modernise their military forces, not only to acquire weapons but also to develop their defence industries in the long term.

For South Korea, defence exports to Southeast Asia are advantageous in many ways. The most direct is the economic impact of defence exports. Exporting weapons and equipment is one thing, but the need for constant aircraft maintenance, ships, etc. also generates economic benefits. Korean defence exports are often more competitive in price or superior in quality than exports from other countries. In addition, the level of military modernisation that Southeast Asian countries are currently seeking is not the expensive, high-tech weapons produced by the United States. Southeast Asian countries want affordable and reliable weapons systems, and there are few countries, including the United States, that can supply them. For South Korea, the Southeast Asian market is a critical market for maintaining the production of weapons systems that are not state-of-the-art but have a certain level of performance, as the country needs a high-low mix of state-of-the-art and second-tier weapons systems for efficient utilisation of resources. South Korea’s exports are naturally positive for the interoperability of weapons systems between South Korea and ASEAN countries and between South Korea, the United States, and ASEAN. The mutual trust generated by such cooperation is also the basis for advancing to higher levels of defence and security cooperation.

Despite its many advantages, defence cooperation and exports between ASEAN and Korea are not all positive. As it involves defence capabilities and potentially lethal weapons, it must be approached with caution. First and foremost, ASEAN-ROK defence cooperation and South Korea’s defence exports to ASEAN should be premised on peace, as paradoxical as that may sound. It should be made clear in advance that ASEAN-ROK defence and defence cooperation is for ‘adequate defence’ to help Southeast Asian countries build defence capabilities commensurate with their size and economic strength. It should also be about military modernisation to the extent that they can adequately respond to the security threats they face. Securing adequate defence capabilities through the military modernisation of Southeast Asian countries is the way to maintain peace in the region. At the same time, it is necessary to be cautious and vigilant to ensure that Korea’s defence cooperation with Southeast Asia and Korea’s defence industry cooperation with Southeast Asian countries do not contribute to the suppression of domestic political forces or the repression of ethnic minorities. We must ensure that Korean-made weapons and Korean assistance are not misused in this way.

Appendix 1. Defense Budget Increase, 2000 to 2021 in Southeast Asia

* for Laos, the numbers are for 2000 and 2013, and for Vietnam, 2003 and 2017

Based on World Bank Data. “Military Expenditure (current USD)”

(https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.CD)

Appendix 2. 10-year Average Defense Spending/GDP Ratio of Southeast Asian Countries

Based on World Bank Data. “Military Expenditure (% of GDP)”

(https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS)

Appendix 3. Arms Imports by Major Southeast Asian Countries after 2000 (USD million)

Based on World Bank Data. “Arms Imports (SIPRI trend indicator values)”

(https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.MPRT.KD)

Appendix 4. Major Korean Arms Exports to Southeast Asia in Recent Years

Appendix 5. Korea’s Assistance to Southeast Asian Navies

This article is an English Summary of Asan Issue Brief (2023-15).

(‘최근 동남아 군비 증강의 이해: 최소한의 군사적 대응능력 확보 의지’, https://www.asaninst.org/?p=89750)

- 1. For example, see Joshua Kurlantzik. 2010. “The Southeast Asian Arms Race.” Asia Unbound. October 20 (https://www.cfr.org/blog/southeast-asian-arms-race); Brijesh Khemlani. 2011. “Southeast Asia’s Arms Race.” RUSI Commentary. January 13 (https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/southeast-asias-arms-race); James Guild. 2022. “Is There an Arms Race Underway in Southeast Asia?” The Diplomat. February 8.

- 2. Based on statistics from World Bank Data. “Military Expenditure (current USD)” (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.CD).

- 3. Based on statistics from World Bank Data. “Military Expenditure (% of GDP)” (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS)

- 4. Based on statistics from World Bank Data. “Arms Imports (SIPRI trend indicator values)” (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.MPRT.KD)

- 5. David Hutt. 2022. “Why Southeast Asia continues to buy Russian weapons.” DW (Deutsche Welle). May 4 (https://www.dw.com/en/why-southeast-asia-continues-to-buy-russian-weapons/a-61364950

- 6. For example, see Sheryn Lee. 2015. “Asia’s Lethal Naval Arms Race.” The National Interest. July 2; Lindsay Murdoch. 2012. “Arms Race Explodes as Neighbours Try to Counter China.” The Sydney Morning Herald. November 19; Richard Bitzinger. 2007. “The China syndrome: Chinese Military Modernization and the Rearming of Southeast Asia.” RSIS Working Paper 126:7.

- 7. Colin Gray. 1971. “The Arms Race Phenomenon.” World Politics 24:1.

- 8. Felix K. Chang. 2021. “Southeast Asian Naval Modernization and Hedging Strategies.” Asan Forum. December 29 (https://theasanforum.org/southeast-asian-naval-modernization-and-hedging-strategies/#6).

- 9. Robert Dayley. 2020. Southeast Asian in the New International Era (London: Routledge). p. 44.

- 10. Andrew Tan. 2004. “Force modernisation trends in Southeast Asia.” RSIS Working Paper No. 59 (Singapore: Nanyang Technological University). p. 22.

- 11. David Shambaugh. 2020. Where Great Powers Meet: America and China in Southeast Asia (New York: Oxford University Press). p. 90-93.

- 12. Aurel Croissant and Philip Lorenz. 2018. Comparative Politics of Southeast Asia: An Introduction to Governments and Political Regimes 1st ed. (Cham.: Springer). p. 164-165.

- 13. Before the creation of ASEAN in 1967, the region had diverse sources of regional disputes. See Rodolfo C. Severino. 2006. Southeast Asia in Search of an ASEAN Community: Insights from the former ASEAN Secretary-General (Singapore: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute). p. 161-164, 207-208.

- 14. Felix Heiduk. 2018. “Is Southeast Asia really in an arms race?” East Asia Forum. February 21. (https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2018/02/21/is-southeast-asia-really-in-an-arms-race/); McKinsey & Company. 2014. “Southeast Asia: The next growth opportunity in defense.” McKinsey Innovation Campus Aerospace and Defense Practices. February. p. 17.

- 15. Felix Heiduk. 2018. “Is Southeast Asia really in an arms race?” East Asia Forum. February 21. (https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2018/02/21/is-southeast-asia-really-in-an-arms-race/).

- 16. Evan A. Laksmana. 2018. “Is Southeast Asia’s Military Modernization Driven by China? It’s Not That Simple.” Global Asia. 13:1.

- 17. Originally from The Straits Times. 2012. “President Defends Jakarta’s Planned Arms Buy.” February 3. Quoted from Felix Heiduk. 2017. “An Arms Race in Southeast Asia? Changing Arms Dynamics, Regional Security and the Role of European Arms Exports.” SWP Research Paper. No. 10. P. 26.

- 18. Evan A. Laksmana. 2018. “Is Southeast Asia’s Military Modernization Driven by China? It’s Not That Simple.” Global Asia. 13:1.

- 19. Felix Heiduk. 2017. “An Arms Race in Southeast Asia? Changing Arms Dynamics, Regional Security and the Role of European Arms Exports.” SWP Research Paper. No. 10. p. 25.

- 20. Simon T. Wezeman. 2011. “The maritime dimension of arms transfers to South East Asia, 2007-11.” SIPRI Yearbook 2012: Armaments, Disarmament and International Security. p. 280.

- 21. Gilang Kembara. 2022. “Indonesia-ROK Maritime Security Cooperation.” In Andrew W. Mantong and Waffaa Kharisma (Eds.), Navigating Unchartered Waters: Security Cooperation between ROK and ASEAN (Jakarta: Centre for International and Strategic Studies). p. 52-54.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter