Introduction

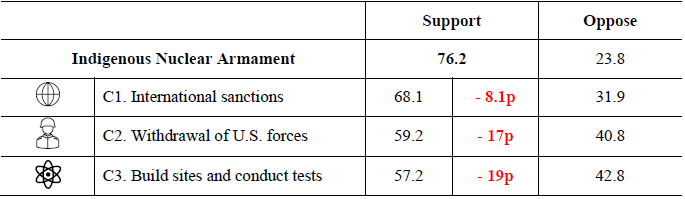

How badly do South Koreans want nuclear weapons? The 2025 Asan Poll found a record 76.2% public support for acquiring an indigenous nuclear weapons capability and 66.3% support for the redeployment of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons to the Korean Peninsula. One of the main critiques of such findings is that the headline figures misrepresent the public’s true commitment to nuclear armament or redeployment. That is, support is expected to dramatically drop when people are asked to consider the potential costs of acquiring nuclear weapons. This Asan Issue Brief introduces the results of a series of conditions-based questions to test the robustness of South Korean public commitment to enhanced nuclear options. The five conditions include a willingness to face international sanctions, risk the withdrawal of U.S. forces from the Korean Peninsula, build storage facilities and conduct nuclear tests, increase defense cost-sharing with the United States, and host tactical nuclear weapons in their city or province.

The Issue Brief finds that a majority of the South Korean public is now committed to both nuclear armament and nuclear redeployment even in the face of four out of five potential cost conditions due to record-high threat perceptions and concerns about the U.S. security commitment. The high headline support for nuclear armament (76.2%) and nuclear redeployment (66.3%) means that even substantial drops in support no longer fall below majority support. However, the South Korean public is most sensitive to specific and tangible potential costs that have a direct impact on them, including hosting deployment of weapons as well as storage and testing facilities in their locality, whereas abstract and unspecified costs only have a modest impact on commitment. While indigenous nuclear armament appears to enjoy higher levels of support over nuclear redeployment, rather than being indicative of public preference, we hypothesize that more specific and tangible cost conditions would quickly erode the headline figure given indigenous nuclear armament will involve much higher costs, potentially involving all five conditions occurring simultaneously, than nuclear redeployment within an alliance framework. In conclusion, our results suggest that public sentiment represented by the headline figures is best understood as a reflection of dissatisfaction with current deterrence measures.

The Issue Brief proceeds as follows. First, it explains the failure of existing ROK-U.S. extended nuclear deterrence measures to reassure the South Korean public, whose threat outlook is more severe than ever. It shows that alternative nuclear options have record levels of support, including indigenous nuclear armament and the redeployment of U.S. nuclear weapons. Second, it reviews the three conditions used to test the strength of public commitment to indigenous nuclear armament, including a willingness to face international sanctions, risk the withdrawal of U.S. forces, and build storage facilities and conduct nuclear tests. Third, it reviews the two conditions for nuclear redeployment, including a willingness to increase defense cost-sharing with the United States and host tactical nuclear weapons in their city or province. Fourth, it discusses policy implications and offers recommendations, including about the strength of headline support, the role of specific and tangible costs, the viability of nuclear redeployment over indigenous armament, and the need for further survey experiments and focus group interviews to identify the specific pathways for maintaining support for stronger nuclear options.

1. Rising Insecurity, Falling Credibility, and Nuclear Options

The alignment of North Korean, Chinese, and Russian nuclear threats is more serious than ever. Meanwhile, the Republic of Korea (ROK) and United States (U.S.) governments continue to insist on “the ironclad U.S. extended deterrence commitment to the ROK, which is backed by the full range of U.S. capabilities, including nuclear.”1 The Joe Biden administration tried to reassure ROK officials with the Washington Declaration and Nuclear Consultative Group (NCG), but while they may have assuaged experts and policymakers, these efforts have not had a discernible effect on the South Korean public.2 Instead, a majority of South Koreans now question the “ironclad” U.S. extended deterrence commitment.3 The erosion of confidence in U.S. extended deterrence has also been influenced by President Trump’s tacit acknowledgement of North Korea as a “nuclear power” and his past record of criticizing the ROK-U.S. alliance and the U.S. defense commitment to South Korea.4

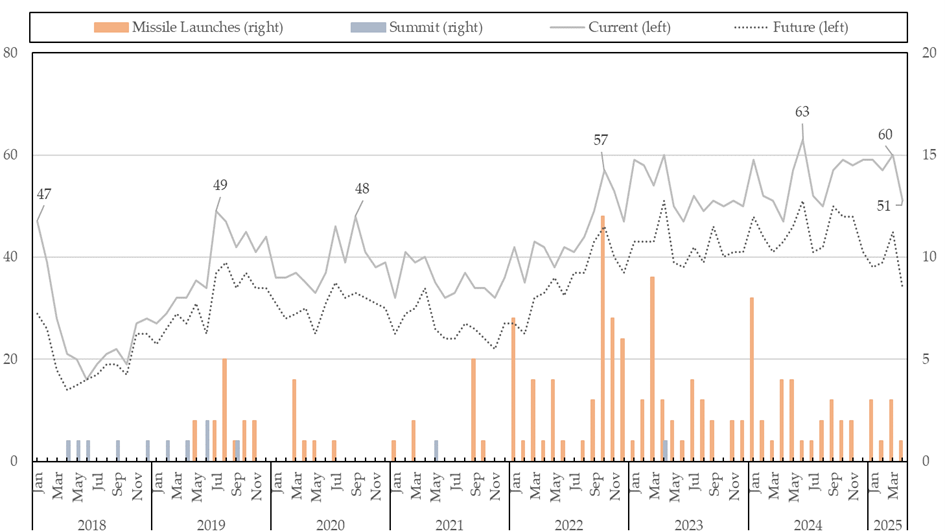

This pessimism is reflected in the high level of perceived security threat expressed by the South Korean public in recent years.5 Figure 1 illustrates the steady increase in threat perceptions about the current and future national security situation since 2019. This escalation, which also correlates with the frequency of North Korean missile launches, has contributed to a shift in South Korean attitudes.6 Despite the recent decline, in April 2025, 51% still hold a pessimistic view of the current national security environment. The persistent presence of the North Korean threat as a structural factor has reinforced public support for stronger deterrent options. And the 2025 Asan Poll, conducted in March 2025 following the start of President Donald Trump’s second term, found that 74.2% of respondents believed the U.S. security commitment to South Korea would weaken—potentially further deepening public skepticism toward the U.S. nuclear umbrella.7

Figure 1. Negative Views on National Security8 (left: %, right: number of times)

For those unsatisfied with the status quo and wanting stronger deterrence options, the debate now broadly divides between those advocating for an indigenous nuclear weapons capability,9 those calling for the redeployment of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons,10 and those seeking some form of nuclear latency.11 According to the March 2025 Asan Poll, public support for acquiring an indigenous nuclear weapons capability reached an all-time high of 76.2% (Oppose: 23.8%).12 This is the highest figure since the Asan Institute began surveying this issue in 2010 (min: 54.8%, max: 76.2%).13 Support for redeploying U.S. tactical nuclear weapons to the Korean Peninsula has also increased to 66.3% (Oppose: 33.7%).14 South Korean public sentiment has remained largely unchanged since 2020 (min: 59%, max: 66.3%).15 This appears to be a mixture of two factors: a cumulative increase in public anxiety driven by repeated North Korean provocations, and a gradual erosion of trust in the U.S. nuclear umbrella.

Overall, these findings suggest that public support for nuclear armament in South Korea is unlikely to dissipate unless the United States takes more visible and concrete steps to strengthen its security commitments. Similar dynamics are unfolding in Europe, where President Trump’s remarks about a potential U.S. withdrawal from NATO have reignited debates over nuclear self-reliance.16 Both cases reflect growing skepticism toward U.S. security guarantees and a shifting calculus among the allies under intensifying geopolitical threats.

Figure 2. South Korean Support for Nuclear Armament: 2010-202517 (%)

Given these trends and debates, how badly do South Koreans really want nuclear weapons? One of the main critiques of such public opinion findings is that the headline figures misrepresent the public’s true commitment to nuclear armament. That is, the level of support is expected to dramatically drop when people are asked to consider the potential costs of indigenously acquiring nuclear weapons or seeking their redeployment to the Korean Peninsula—whether reputational, financial, diplomatic, military, or otherwise. Put another way, when respondents are asked about what sounds like an attractive idea, such as whether they would like a luxury sports car or support inter-Korean unification, without asking about the costs involved, then it is difficult to know the true commitment.18 For the nuclear non-proliferation community and advocates of inter-Korean denuclearization, the best strategy is therefore to dissuade nuclear appetites by highlighting the potential costs of nuclear armament.19

2. Public Support for Indigenous Nuclear Armament

The Asan Institute’s public opinion surveys have been among the longest and most consistent within the growing body of survey work on South Korean nuclear attitudes.20 This section introduces the results of a series of five conditions-based questions used in the 2025 Asan Poll designed to test the strength of South Korean public commitment to enhanced nuclear options. The three conditions for indigenous nuclear armament include a willingness to face international sanctions, risk the withdrawal of U.S. forces, and build storage facilities and conduct nuclear tests. The two conditions for nuclear redeployment include a willingness to increase defense cost-sharing with the United States and host tactical nuclear weapons in their city or province.

The five conditions are separated between the indigenous nuclear armament and nuclear redeployment options. This is because nuclear redeployment should be easier to implement than indigenous nuclear armament given that nuclear redeployment is only possible within the framework of the ROK-U.S. alliance and with the assistance of the United States. The United States deployed almost 1,000 tactical nuclear weapons in South Korea during the Cold War in the 1960s.21 It also involves lower proliferation risks given that South Korea would not have direct possession or launch authority over the re-deployed weapons. By contrast, indigenous nuclear armament would have to be pursued independently, or at least without U.S. nuclear weapons. Therefore, the latter two conditions asked for nuclear redeployment—whether respondents would support increased defense cost-sharing with the United States and host redeployed tactical nuclear weapons in their city or province—would both apply to the nuclear armament case, but not necessarily the other way around. Put simply, nuclear redeployment should be less costly than indigenous nuclear armament; any costs incurred in the redeployment scenario would be magnified in an indigenous nuclear armament scenario.

The results for indigenous nuclear armament are presented below. The results suggest that, for a majority of the South Korean public, the nuclear juice is worth the squeeze of potential costs. While there are clear decreases in commitment when faced with potential costs as expected, a majority continued to support nuclear armament.22 This was because support for indigenous nuclear armament has reached such high levels in the face of severe external threats and deterrence credibility shortfalls.

Table 1. Support for Conditions-based Indigenous Nuclear Armament (%)

Condition 1. International sanctions

When asked about the risk of facing international sanctions, there was an 8.1%p decrease in support for nuclear armament to 68.1%. This modest decrease suggests a hardening of nuclear preferences over time, which resonates with the previous results of Asan Polls conducted between 2022 (’22: 70.2→63.6%, ’23: 66.7→61.1%) and 2024 (70.9→61.7%). Consistently, less than 10% of respondents changed their positions on developing indigenous nuclear weapons when they were exposed to a condition of international sanctions. While conditional costs do temper nuclear commitment, the support for nuclear armament remains robust in the 2025 Asan Poll. When faced with the prospect of international sanctions, support for indigenous nuclear armament remained relatively resilient at 68.1%. Also, a similar survey reported that while drops in support were 23.5%p under the conditions of economic sanctions in 2023, the decline narrowed to 15.9%p in 2024—likely due to growing tolerance for economic costs. It should be noted that the question did not ask respondents about specific costs either for the country as a whole or on an individual household basis.

Condition 2. Withdrawal of U.S. forces

When asked about the risk of a withdrawal of U.S. forces from Korea, there was a 17%p decrease in support for nuclear armament to 59.2%. This is only marginally smaller than the 20%p decrease in previous years, but because of the high overall support for nuclear armament, it means that this year a majority of respondents ended up being committed to indigenous nuclear armament even in the face of a U.S. troop withdrawal threat. Across multiple surveys conducted by various Korean pollsters between 2023 and 2024, support for nuclear armament consistently declined by approximately 20%p when respondents were asked to consider the possible withdrawal of U.S. troops from South Korea (’23: 23.1%p, ’24: 21%p).23 This suggests a widespread public recognition of the critical role played by U.S. forces in South Korea for its national security. The relatively stable response tendency over time highlights how visible and tangible the U.S. military presence remains in the public’s perception of deterrence. While public responses to the economic sanction scenario differ by polling institution and period, the attitude change by the withdrawal of U.S. forces from South Korea remains consistent.

South Korea’s decision to forego nuclear weapons was made in exchange for the U.S. nuclear umbrella, including the stationing of U.S. troops. Against this backdrop, the above findings suggest that the public continues to view the presence of U.S. forces as a cornerstone of national security, outweighing other potential trade-offs. These findings have significant implications in light of President Trump’s transactional approach to alliances in both the Indo-Pacific and Euro-Atlantic regions. The fact that South Koreans showed greater sensitivity to the potential withdrawal of U.S. forces underscores widespread recognition of the necessity of the U.S. military presence in the alliance framework.

Condition 3. Build sites and conduct tests

When asked about the need to build nuclear weapons and waste storage facilities as well as conduct nuclear weapons tests, there was a 19%p decrease in support for nuclear armament to 57.2%. Beyond economic burdens, pursuing nuclear armament entails significant technical and infrastructural challenges. In addition to securing the financial resources, it requires South Korea to establish and manage domestic facilities for spent fuel reprocessing and uranium enrichment—prerequisites for developing nuclear weapons. While some point to the case of Israel acquiring a de facto nuclear status without conducting nuclear tests, and suggest that simulations could substitute for testing, it is nonetheless worth pushing respondents to consider the tangible costs of building such facilities. The 2025 Asan Poll first introduced such infrastructural requirements as a cost factor to assess their impact on public opinion. By framing nuclear reprocessing and enrichment facilities as essential, the survey aimed to more accurately gauge how realistic trade-offs might shift support for nuclear armament among South Koreans. This divergence shows that the public perceives establishing and operating nuclear facilities as greater and more tangible risks than the abstract economic burdens of potential withdrawal from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and resulting international sanctions. The burden of constructing nuclear development and waste processing facilities—along with the potential need for nuclear testing—was perceived as more significant than the projected ripple effects of international economic sanctions.

However, public concern over international sanctions could plausibly increase if specific information cues—such as reductions in personal income—were introduced. An experimental study examining public attitudes toward nuclear armament under hypothetical sanction scenarios found that providing specific information on expected outcomes, particularly income losses, reduced support for nuclear armament. The study segmented the duration of income loss from six months to six years, with additional distinction between temporary and permanent impacts.24 While these findings are valid and generally accepted, the present study did not incorporate such detailed scenario conditions. Rather than exploring cost sensitivity across individual trade-offs, this study aimed to assess the overall resilience of public support for nuclear armament over time, particularly in the context of sustained North Korean threats and declining trust in U.S. security commitments.

3. Public Support for Redeployment of U.S. Nuclear Weapons

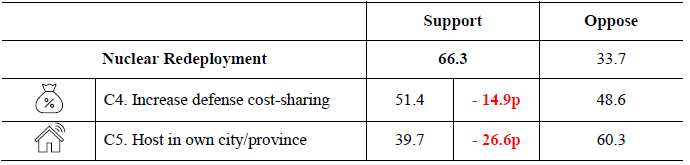

Compared to the substantial hurdles involved in pursuing an indigenous nuclear weapons capability, another nuclear option being debated is the redeployment of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons, otherwise known as non-strategic nuclear weapons, to the Korean Peninsula which were previously withdrawn in 1991. In 2025, 66.3% of respondents supported the redeployment of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons. This option has gained significant traction, especially among conservatives, who support it by 84.2%, though progressives also support the idea by 58.2% (Oppose: 41.8%). The two conditions tested for nuclear redeployment include a willingness to increase defense cost-sharing with the United States and host tactical nuclear weapons in their city or province. Of course, due to the baseline support (i.e., 66.3%) for redeploying U.S. tactical nuclear weapons, the respondents had come to be evenly split when they were exposed to the potential costs of nuclear redeployment. The exception was a 26.6%p decrease when respondents were asked to host nuclear weapons in their city or province, making it the only condition in which opposition exceeds support.

Table 2. Support for Conditions-based Redeployment of U.S. Nuclear Weapons (%)

Condition 4. Increase defense cost-sharing

When asked whether they would support an increase in ROK-U.S. defense cost-sharing in return for the redeployment of nuclear weapons, there was a 14.9%p decrease in support to 51.4% resulting in an even split between support and opposition. Though it was not able to specify the potential costs for nuclear armament in the questions, it is assumed that hosting U.S. tactical nuclear weapons would entail substantial expenses. In particular, under the second Trump administration, which has openly stated intentions to increase alliance cost-sharing, it is reasonable to expect that the financial burden for South Korea would grow significantly. It suggests that cost-sharing could emerge as a contentious issue in any future discussion on the redeployment of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons. As President Trump has consistently emphasized increasing allies’ financial contributions to defense, if a redeployment were pursued during his presidential term, South Korea could face heightened demands for alliance burden-sharing. While U.S. tactical nuclear redeployment is often regarded as a more feasible alternative to indigenous nuclear armament, it is not without costs. If the associated financial burden becomes more visible or concrete, the public sentiment towards it could shift. In fact, similar trends have been observed in countries such as Germany and Italy, where majority support for the withdrawal of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons has been recorded.25 Once hosting costs for South Korea are scrutinized, there could be a comparable public sentiment shift.

Condition 5. Host in own city/province

When asked whether they would support the redeployment of nuclear weapons to their city or province, there was a 26.6%p decrease in support to 39.7%. This was the only condition in which support fell below 50%. This reflects a broader pattern of public resistance toward hosting “Not In My Backyard” (NIMBY) facilities such as nuclear infrastructure. Considering the strong opposition experienced during the deployment of the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system in Seongju in 2017, the sharp decline in support is not surprising. From an operational perspective, the B61 nuclear gravity bombs that the United States had previously deployed to South Korea during the Cold War were based at Kunsan Air Base in North Jeolla Province. While the sample size for this region in the 2025 survey was small (n= 97) and does not allow for definitive conclusions, it is notable that only 26.2% expressed support for hosting nuclear weapons. Similarly, Osan Air Base in Gyeonggi Province, which would be an alternative site for hosting any redeployed U.S. nuclear weapons, also only recorded 36.1% support from a sample of 322 people, albeit also including residents from Incheon.26 But there was one caveat to this result, with 51.8% of men being in the affirmative and only 27.9% of women agreeing. Of those who had performed military service, 51.2% were supportive, while only 29.7% of those who had not served were supportive.

4. Policy Implications and Recommendations

These findings have significant implications for understanding the South Korean nuclear debate. First, the public’s commitment may be firmer and more resilient than previously assumed.27 Our findings suggest that existing assumptions need to be revisited in the strategic context of 2025—characterized by heightened North Korean threats and eroding trust in U.S. extended deterrence. Public attitudes have evolved to become more enduring and resilient. The perceived security benefits of having access to nuclear weapons increasingly outweigh the potential costs for a majority of the public. While support for both nuclear options reflects a growing desire for more credible nuclear deterrence, they differ significantly in terms of political feasibility, legal implications, and alliance dynamics. However, this support remains sensitive to shifts in the security environment, policy responses, and political context.

Second, public commitment decreases most sharply when presented with more tangible conditions, such as willingness to host weapons, rather than vague costs. The sharp 26.6%p fall in condition 5 on the NIMBY effect especially shows that any attempt at nuclear redeployment would first need to make a significant investment in securing a social license to operate at both a national level and especially with the affected communities. The same applies for the construction of weapons facilities, which appear to have a more tangible effect than the risk of international sanctions. This suggests that the demand curve for nuclear options only begins to fall closer to implementation, which is later than often assumed. Any future move toward nuclear redeployment would therefore require significant efforts to secure public consent, especially at the local level. Further research is needed to understand a wider number of conditions and phased levels of commitment.

Third, when considering the cumulative costs South Korea would incur in pursuing indigenous nuclear armament—including legal, technical, political, and diplomatic burdens—the redeployment of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons emerges as a more viable alternative. In this survey, each condition for indigenous armament was given separately, but if South Korea were to pursue nuclear armament, all five costs would likely occur in succession or simultaneously. While the decline in support under each condition cannot simply be aggregated, it is clear that the cumulative cost of pursuing nuclear weapons would be substantial. For a non-nuclear state like South Korea operating within the nonproliferation regime, this makes indigenous nuclear armament a far more complex and difficult path. Therefore, nuclear redeployment would be the more feasible nuclear option. Further studies, including survey experiments and focus group interviews, would help identify the specific pathways under which implementation of nuclear redeployment might maintain public support, only if the cost details are formally introduced into the policy discourse. For example, given the strong public opposition to hosting nuclear weapons, a flexible basing model could offer a workable compromise. This could involve constructing storage facilities dual-capable of receiving tactical nuclear weapons during heightened contingencies, without requiring permanent stationing.28 Further surveys on whether the public would prefer these options, and at what cost, would improve understanding of public sentiment.

Conclusion

For a majority of the South Korean public, stronger nuclear options are indeed worth the squeeze of potential costs. As with previous studies, public support for nuclear armament and redeployment—as measured through conditional survey items—declined when specific costs or trade-offs were introduced. This is consistent with earlier findings in the literature, where support has proven sensitive to how nuclear options are framed. Of course, these attitudes are not static. Public opinion on nuclear armament is likely to fluctuate depending on the security environment, cost-sharing burdens, and both domestic and international political dynamics. The survey results shown in this Asan Issue Brief reveal a level of support for nuclear armament and redeployment that is more resilient than expected. Given these findings, further empirical validation of South Korean attitudes toward nuclear options is essential. Sustained public endorsement, despite hypothetical costs, warrants close observation.

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 1. “Fact Sheet: The United States of America-Republic of Korea Nuclear Consultative Group (NCG),” January 14, 2025, https://kr.usembassy.gov/011425-the-united-states-of-america-republic-of-korea-nuclear-consultative-group-ncg/.

- 2. Peter K. Lee and Chungku Kang, “Comparing Allied Public Confidence in U.S. Extended Nuclear Deterrence,” Asan Issue Brief, March 2024, https://en.asaninst.org/contents/comparing-allied-public-confidence-in-u-s-extended-nuclear-deterrence/.

- 3. KINU, “North Korea’s Two Hostile States Doctrine and South Korean Attitudes towards Nuclear Armament (북한의 적대적 2국가론과 한국의 핵보유 여론),” Korea Institute for National Unification, February 25, 2025, https://www.kinu.or.kr/main/module/report/view.do?idx=128256&nav_code=mai1674786094.

- 4. Stella Kim and Mithil Aggarwal, “Trump calls North Korea a ‘nuclear power,’ drawing a rebuke from Seoul,” NBC News, January 21, 2025, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/trump-calls-north-korea-nuclear-power-drawing-rebuke-seoul-rcna188490.

- 5. According to the survey data released by Hankook Research, the perceived threat has gradually increased since 2018.

- 6. Yewon Kwon, Kyungsuk Lee (2024), “Revisiting inter-Korean events and South Koreans’ perception on unification,” Social Science Quarterly, 105(6), https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ssqu.13453.

- 7. Asan Poll (March 6~8, 2025). The survey was conducted by Embrain Public using RDD for mobile and landline on March 6~8, 2025 with a representative sample of 1,000 respondents (weighted) over the age of 19 across South Korea with a margin of error of ±3.1%p at the 95% confidence level.

- 8. Chungku Kang, “South Korean Perception of Nuclear Proliferation,” WAPOR Presentation, June 29, 2024, https://wapor.org/wp-content/uploads/Kang-South-Korean-Perception-of-Nuclear-Proliferation-1.pdf. Figure 1 is an update of Figure 2 in the file above. Perceived threat was alternatively measured by the negative views of current or future national security environments. The authors compiled the data for North Korean provocations including missile launches, and nuclear tests by a month based on accessible open-source materials. And the data on North Korean missile launches in Figure 1 indicates whether a missile launch occurred on a given day which are categorized in a month, rather than the number of projectiles launched.

- 9. Hwee-rhak Park, “A Non-nuclear US Ally’s Nuclear Option: South Korea’s Case,” e12:1 (2024), https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/23477970241298760

- 10. Roger F. Wicker, “21st Century Peace Through Strength: A Generational Investment in the U.S. Military,” May 29, 2024, https://www.wicker.senate.gov/2024/5/senator-wicker-unveils-major-defense-investment-planl; David Phillips, “Nuclear Redeployment: A Roadmap for Returning Nonstrategic Nuclear Weapons to the Korean Peninsula,” On the Horizon: A Report of the CSIS Project on Nuclear Issues, Center for Strategic and International Studies, December 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/horizon-vol-7, pp. 12-38.

- 11. In this Issue Brief, we set aside the nuclear latency argument which is not mutually exclusive with the first two propositions. Min Chul Gu, “South Korean politicians push for nuclear capability,” Defense Blog, February 4, 2025, https://defence-blog.com/south-korean-politicians-push-for-nuclear-capability/.

- 12. Question wordings for Asan Poll 2025 are as follow: a) Acquiring indigenous nuclear weapons: Q. What is your opinion about the statement that South Korea should develop nuclear weapons? b) Reintroducing U.S. tactical nuclear weapons: Q. What is your opinion about the statement that U.S. tactical nuclear weapons should be deployed in South Korea?

- 13. This was statistically the same with another poll asking whether South Korea should acquire nuclear weapons if North Korea were recognized as a nuclear weapons state (74%). KBS, “New Year’s Opinion Poll by KBS(“KBS 설특집 여론조사”),” KBS, January 28, 2025, https://news.kbs.co.kr/news/pc/view/view.do?ncd=8162418.

- 14. Since 2013 when the Asan Institute first began gauging public opinion on this issue, a majority have consistently supported it.

- 15. The only exception was in March 2019, when public opinion was evenly split over it (Support: 46%, Oppose: 47.9%).

- 16. Astrid Chevreuil and Doreen Horschig, “Can France and the United Kingdom Replace the U.S. Nuclear Umbrella?,” Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), March 4, 2025,

https://www.csis.org/analysis/can-france-and-united-kingdom-replace-us-nuclear-umbrella. - 17. Asan Institute, “South Koreans and Their Neighbors 2025”, Asan Institute for Policy Studies, April 28, 2025.

- 18. Hong Jepyo, “Trade-Offs Behind South Korea’s Nuclear Ambitions (핵무장 지지의 허와 실),” CBS News, July 17, 2024, https://www.nocutnews.co.kr/news/6178942.

- 19. Jun Bong-geun and Joel Petersson-Ivre, “Drivers and Constraints of Nuclear Proliferation: Regional Responses to South Korean Nuclear Armament,” Asia-Pacific Leadership Network, December 18, 2024, https://www.apln.network/projects/nuclear-order-in-east-asia/drivers-and-constraints-of-nuclear-proliferation-regional-responses-to-south-korean-nuclear-armament; Alexander M. Hynd, “Dirty, Dangerous… and Difficult? Regional Perspectives on a Nuclear South Korea,” Journal of Asian Security and International Affairs, 12:1 (2024), 54-80. https://doi.org/10.1177/23477970241298756; Joel Petersson-Ivre, “The South Korean Anti-Nuclear Weapons Movement Must Find Its Voice,” Asia-Pacific Leadership Network, August 22, 2024, https://www.apln.network/projects/nuclear-order-in-east-asia/the-south-korean-anti-nuclear-weapons-movement-must-find-its-voice.

- 20. For more recent efforts, see Toby Dalton, Karl Friedhoff, and Lami Kim, Thinking Nuclear: South Korean Attitudes on Nuclear Weapons (Chicago: The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, February 2022), https://globalaffairs.org/research/public-opinion-survey/thinking-nuclear-south-korean-attitudes-nuclear-weaponsl; Chey Institute for Advanced Studies, “Korean Perceptions toward the North Korean Nuclear Crisis and the Security Environment,” January 30, 2023, https://www.chey.org/Eng/Issues/IssuesContentsView.aspx?seq=695.

- 21. Choi Kang and Peter K. Lee, “A Sixties Comeback: Restoring U.S. Nuclear Presence in Northeast Asia,” Asan Issue Brief, May 2025, https://en.asaninst.org/contents/a-sixties-comeback-restoring-u-s-nuclear-presence-in-northeast-asia/.

- 22. Kyungsuk Lee, “South Korean Cost Sensitivity and Support for Nuclear Weapons,” Empirical and Theoretical Research in International Relations, 50:3 (2024), https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03050629.2024.2348063.

- 23. KINU, “South Korean Public Opinion towards Nuclear Armament(한국의 자체적 핵보유 가능성과 여론),” Korea Institute for National Unification, June 5, 2023,

https://www.kinu.or.kr/main/module/report/view.do?idx=114284&nav_code=mai1674786536 - 24. Yoo Jeong Lee, “A Resilient Core: 37% Support Nuclear Armament Even Under Permanent Economic Sanctions (영구 경제 제재 받아도 韓 핵무장”…콘크리트 지지층 37%),” JoongAng Daily, October 10, 2024, https://www.joongang.co.kr/article/25283398

- 25. Majorities in European countries hosting U.S. nuclear weapons want them removed from their soils—83% of Germans, 74% of Italians, 58% of Dutch and 57% of Belgians. ICAN, “NATO Public Opinion on Nuclear Weapons,” The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, January 2021, https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/ican/pages/234/attachments/original/1611134933/ICAN_YouGov_Poll_2020.pdf.

- 26. Though these figures should be interpreted with caution due to sample limitations, they nonetheless suggest the potential for significant local resistance in areas historically associated with U.S. nuclear basing.

- 27. KINU, “South Korean Public Opinion towards Nuclear Armament (한국의 자체적 핵보유 가능성과 여론),” Korea Institute for National Unification, June 5, 2023,

https://www.kinu.or.kr/main/module/report/view.do?idx=114284&nav_code=mai1674786536. - 28. David Phillips, “Nuclear Redeployment: A Roadmap for Returning Nonstrategic Nuclear Weapons to the Korean Peninsula,” On the Horizon: A Report of the CSIS Project on Nuclear Issues, Center for Strategic and International Studies, December 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/horizon-vol-7, pp. 12-38.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter