Introduction

North Korea’s third nuclear test had been anticipated for weeks, and in its wake came the traditional condemnations from relevant countries and international institutions. But a newer feature of the media coverage is the focus on the reaction, or lack thereof, of the South Korean public. Media reports have rightly identified that the South Korean public has largely reacted with a shrug to both missile launches last year — in the National Assembly election in April and December’s presidential election less than 5% said that issues related to North Korea were the deciding factor in their vote — and the most recent nuclear test. Some have taken this lack of reaction as a signal that the South Korean public does not take such developments seriously. However, analysis of South Korean public opinion shows that this is not the case.

This report delves deeper into public opinion on issues related to North Korea before and after the February 2013 nuclear test, highlighting South Koreans’ threat perceptions, attitudes on alliances, perceptions of both current and future national security, attitudes on how to best deal with North Korea, and the current opinion on a South Korean nuclear weapons program. It is this public opinion that will help to shape President Park Geun-Hye’s North Korea policy as she assumes office.

South-North relations not seen as national priority…

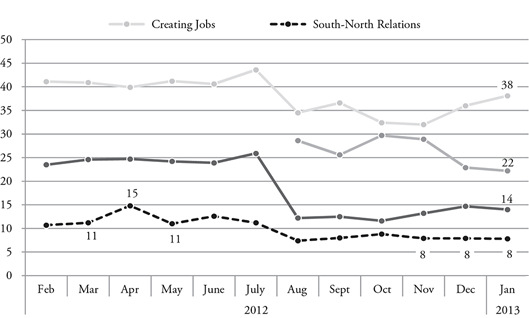

To understand why public reaction has been muted, it should be noted that South-North relations have not been an important issue to the South Korean public over the past year (Figure 1). Instead, the focus has been almost exclusively on South Korea’s considerable domestic challenges and how it will meet them for the next five year —household debt, youth unemployment, wealth disparity, and economic growth have topped the bill.

North Korea’s April 2012 missile test was also welcomed with little response creating a small, but temporary, bump in the perceived importance of South-North relations to the South Korean public. By May it had declined to its original level, and throughout the presidential campaign its importance to the nation remained below 10%. In December, with all eyes on the election, the North’s successful missile launch had no affect whatsoever on the importance of South-North relations to the South Korean public.

Figure 1. Most Salient Issues to the Korean Public

Muted public response, yes, but perceived threat…

Much of the analysis on why the South Korean public’s reaction has been muted has centered on the fact that South Koreans live with these threats on a daily basis and are accustomed to the bluster emanating from North Korea. While this certainly seems to be the case, it should not be understood that South Koreans see the North’s provocations as having no impact on the security of South Korea.

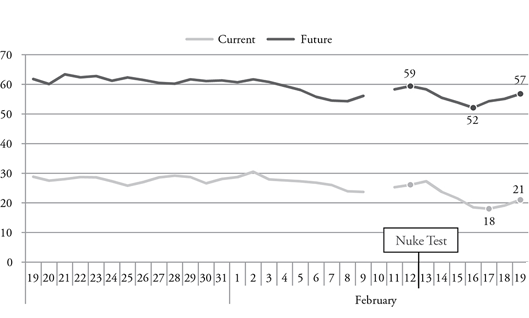

In the month before the February 2013 nuclear test, approximately 28% on average positively assessed the current national security situation (Figure 2). At the same time, roughly 60% on average positively assessed future national security. Immediately following the nuclear test there was an 8pp decline in the positive perception of current national security. At 18%, this was the lowest mark since Asan began tracking this number.

With regard to the positive perception of future national security, there was an immediate 7pp decline in the wake of the North’s test. At 52%, this is also the lowest mark since Asan began tracking the number.

However, these declines were short-lived, illustrating the limited effect North Korea’s non-lethal provocations have on the South Korean public. After hitting bottom at 52%, the positive perception of future national security quickly rebounded, hitting 57% only three days later. The same effect appears to hold true for the impact on the positive perception of current national security. While it bottomed-out one day after the positive perception of future national security, it also began to rebound quickly. On February 19, just two days after reaching a low, it had reached 21% and is expected to continue to rise.

Figure 2. Positive Perception of National Security

Immediately following the test, 63% stated that they felt insecure due to the test.1 In the same survey the North Korean nuclear test was cited by a plurality (40%) as the greatest social risk, followed by violent crime (34%), and fatal diseases such as cancer (13%). One interesting finding to come out of that survey was that among the 36% who reported not feeling insecure due to the North’s nuclear test a plurality (35%) reported not feeling threatened because they viewed the North’s nuclear weapons as a bargaining chip in negotiations with the United States. The next largest segment (32%) cited the fact that they believed there was very little possibility for North Korea to strike South Korea with a nuclear missile.

But these results only provide a snapshot of South Korean threat perceptions and must be interpreted carefully. These measurements were performed at a time when the provocation was fresh, and uncertainty and fear were at their highest. Thus, it will be important to track these issues over time, which in the absence of North Korean provocations, will likely show declines. A better measure of South Korean threat perceptions regarding the North’s nuclear weapons program can be found in repeated measures of the Asan Annual Surveys.

Since 2011 these surveys have asked about the threat perception of North Korea possessing nuclear weapons, an important difference. Responses for both 2011 and 2012 indicated that three-quarters of South Koreans felt threatened by the North’s weapons. Moreover, when asked in 2011 and 2012 if the North would use those weapons should there be a renewal of the Korean War, 54% and 53%, respectively, answered in the affirmative.

There was an interesting distribution across age cohorts on this. One of the most consistent findings of Asan surveys is that Koreans in their 20s identify as security conservative, and often agree very closely with Koreans in their 60s and older on issues related to North Korea. The same applied in this case. While 72% of those 60 or older reported feeling threatened by the most recent test (the highest), 64% of those in their 20s reported the same (second highest). The age cohort which felt least threatened was the 40s, with 51% stating as such.

Since 2010 a similar pattern among age cohorts has emerged in the public’s perception about the possibility of war. While 40% thought war was possible in 2010, by 2012 that number stood at 59%. Among age cohorts, as shown in Table 1, it was South Koreans in their 20s who were most likely to see the renewal of open hostilities as possible. This is consistent with the findings across all three Annual Surveys. The youngest Koreans, while much more progressive on a host of social issues, are decidedly security conservative.

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20s | 45 | 57 | 65 |

| 30s | 38 | 46 | 60 |

| 40s | 39 | 43 | 52 |

| 50s | 38 | 49 | 58 |

| 60s+ | 40 | 56 | 61 |

Clearly, the South Korean public sees North Korea’s weapons and testing as a threat to South Korea. Despite this fact, the importance of South-North relations to the Korean public remains low, and the public will continue to shrug off non-lethal North Korean provocations.

All Provocations Not Created Equal…

North Korea’s provocations come in two distinct varieties—the lethal and the nonlethal. While it has been more than two years since the shelling of Yeonpyeong Island, it was still cited by the second-highest percentage of people (27%) as creating the most insecurity.2 A plurality (31%) cited nuclear weapons testing and 14% cited the sinking of the Cheonan. (Only 8% cited missile launches.) However, this question comes in the immediate aftermath of the third nuclear test, and when the question is repeated in future surveys it will likely decline, leaving the shelling of Yeonpyeong Island as the most often cited.

There was a wide range among cohorts about which provocation created the most insecurity. While respondents 60 or older were most likely to see the North’s nuclear tests as inducing the most insecurity, with 39% stating as such, there was a decline among each subsequent cohort. Only 22% of those in their 20s agreed. Conversely, those in their 20s and 30s were most likely to cite the shelling of Yeonpyeong with 33% of each cohort stating as such. Those in their 60s or older were the least likely to cite this (18%).

Negotiations Favored, But Economic Sanctions Also Supported…

There is clearly no easy way forward for any of the countries involved in trying to divorce North Korea from its nuclear weapons. The military option is largely off the table, economic sanctions have been ineffective due to China’s unwillingness to enforce them, and negotiations have proven frustrating for a variety of reasons.

Despite this, there is little expectation that President Park’s North Korea policy will shift in the wake of the February 2013 nuclear test. A clear majority (67%) supported her directive of trust building with potential engagement in an effort to improve relations with North Korea.3

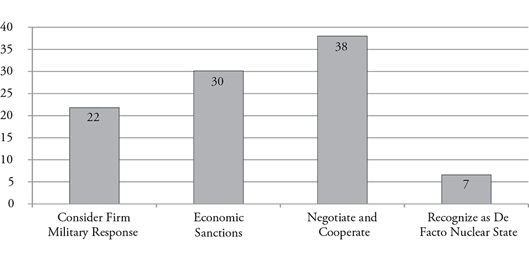

When asked about how to move forward, as shown in Figure 3, a plurality (38%) preferred that South Korea negotiate and cooperate with North Korea to solve the nuclear problem. The second-best option was for continued economic sanctions. There was a surprising amount of support (22%) for the consideration of a firm military response, but here the key is to highlight the use of the word “consider”. In a separate question, 59% opposed a preemptive strike on North Korea’s nuclear test site due to the threat of war. One option that was clearly off the table was the recognition of North Korea as a de facto nuclear weapons state. Only 7% supported this as the best way forward.4

Figure 3. Policy Options

Ambivalence on US Nuclear Umbrella, But US Alliance Indispensable…

One of the core features of the security of South Korea has been its alliance with the United States, and the United States has continually assured South Korea that it falls under the US nuclear umbrella. Despite these assurances, the South Korean public is ambivalent on whether or not the United States would employ its nuclear forces in the event of a North Korean nuclear strike on South Korea.

In 2012, 48% stated that they believed the United States would do so, a 7pp decrease from

2011.5 However, this ambivalence on the US nuclear umbrella should not be interpreted as extending to the alliance itself—support for the alliance is at an all-time high, with 94% support in 2012. Moreover, 61% cite the United States as the country that South Korea should cooperate with most closely to solve the North Korea nuclear problem—30% cited China. But on this, there was a significant divide among political affiliation. While 71% of those who support the conservative Saenuri Party cited the United States, 56% of Democratic United Party supporters stated the same. On China, those numbers were 24% and 35% respectively.6

There was very little support for closer cooperation with Japan, with only 2% citing it as the most important country for South Korea to cooperate with in dealing with North Korea. However, the North Korea nuclear test may have revived support for the General Security of Information Agreement, better known as GSOMIA. In June, just after it failed to be put into force, 44% thought that such an agreement was necessary. Following North Korea’s third nuclear test, 65% saw it as a necessity, opening a window for the Park Geun-Hye administration to both create a more solid foundation for improving national security and work towards better relations with Japan with one deft move.

Growing Support for a Nuclear South Korea…

In 2012, there was continuous, but quiet, discussion about nuclear weapons and South Korea. The first part of the discussion involved the return of US tactical nuclear weapons. The second focused on an indigenous nuclear weapons program. However, the United States made it clear that a return of tactical weapons would not be considered. Following the February 2013 nuclear test, the discussion about an indigenous nuclear weapons program moved from quiet rooms to front pages.

Several prominent lawmakers argued forcefully in the National Assembly that South Korea should undertake its own nuclear weapons program. Clearly, they argued, the international community was unable to stop North Korea from developing nuclear weapons, and that South Korea should not rely on the international community for protection. Instead, it should take responsibility for its own defense, and the ultimate defense would be the development of nuclear weapons. Thus far, the discussion has been one-sided, with those that oppose such a program yet to make a clear, concise argument on why they believe such development would not be in Korea’s interest.

The calls for a domestic weapons program are not out of line with public sentiment. Following the February 2013 nuclear test, 66% of the South Korean public supported a domestic nuclear weapons program—a 10pp increase from 2010 (Figure 4). While there was some division on this across the political spectrum, it is important to note that even among self-identified progressives 58% were in favor, while 71% of conservatives stated the same. Moreover, a majority of all age cohorts except the 20s (49%) were in favor.

Figure 4. Support for Nuclear Weapons

However, what was most interesting about the responses was the change in intensity, as shown in Figure 5. Most notable is the dramatic increase in the percentage of the public that “strongly supports” the development of a domestic nuclear weapons program, and the 13pp decline in those who oppose.

Figure 5. Support for Nuclear Weapons

Conclusion

The policy implications of the public opinion reported here are far-reaching. South Korea as a nation is becoming more confident in its place in the region and the world, and as such it is beginning to redefine its role in both. While the Park administration will begin its term by largely maintaining the hardline policies of the Lee administration, the door for engagement will be left open. What is more concerning, however, is the increasing talk and support for a nuclear weapons program. Such a decision by South Korea would have important implications not only for South Korea but for international arms control regimes. Those who support such a program have already made strong, sovereignty-based arguments on why such a program should be pursued. Those who oppose such a program have yet to clearly lay out how such a program would damage South Korea’s energy, food, and national security rather than bolster it.

Moving forward, the lack of South Korean public response to non-lethal North Korean provocations will continue. There are even signs that international investors are growing more comfortable with this aspect of investing in South Korea, with decreasing instability in the Korean currency and its primary bourse. However, the threat posed by North Korea is seen as increasingly real, and if North Korea sees diminishing returns from its nuclear and missile tests, it may choose to increase the intensity of its provocations.

A note on this report:This report combines the results from multiple surveys conducted since 2010, with the most recent data coming from two surveys conducted immediately following North Korea’s third nuclear test on February 12, 2013. Where necessary, dates for the appropriate surveys are endnoted. More information on each survey can be found in the appendix.

Appendix

Annual Survey 2010: The Asan Annual Survey 2010 was conducted from August 16 to September 17, 2010 by Media Research. The sample size was 2,000 and it was a Mixed-Mode survey employing RDD for mobile phones and an online survey. The margin of error is 2.2% at the 95% confidence level.

Annual Survey 2011: The Asan Annual Survey 2011 was conducted from August 26 to October 4, 2011 by EmBrain. The sample size was 2,000 and it was a Mixed-Mode survey employing RDD for mobile and landline telephones. The margin of error is 2.2% at the 95% confidence level.

Annual Survey 2012: The Asan Annual Survey 2012 was conducted in two parts. The panel survey portion was conducted from September 5 – 14, 2012. The second portion was conducted from September 25 – November 1, 2012 employing RDD for mobile and landline phones. The sample size was 1,500 and the margin of error is 2.5% at the 95% confidence level. The survey was conducted by Media Research.

Asan Daily Survey: The Asan daily Survey uses the three-day rolling average, and employs RDD for mobile and landline phones. The sample size for each is 1,000 and the margin of error is 3.1% at the 95% confidence level. The surveys were conducted by Research & Research.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter