https://www.bbc.com/news/live/uk-politics-64945036?page=2

Introduction

The AUKUS partnership between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States is one of the most audacious defense industrial efforts to meet the challenge of China’s rising military power.1 While most attention has focused on what is called ‘Pillar 1’ to construct a fleet of nuclear-powered, conventionally armed submarines, the three AUKUS countries are also pursuing ‘Pillar 2’ cooperation to develop cutting-edge military technologies that complement the submarine enterprise. Three years since it was announced, the potential expansion of Pillar 2 membership to include other U.S. allies and partners marks a new phase in minilateral security cooperation in the Indo-Pacific.2 But should the Republic of Korea join AUKUS Pillar 2?

This Asan Issue Brief explains what AUKUS Pillar 2 is and considers the costs and benefits of ROK collaboration with the AUKUS enterprise. The Issue Brief proceeds as follows. First, it reviews how the AUKUS partnership has progressed over the past three years across both the Pillar 1 nuclear submarine enterprise as well as the Pillar 2 advanced military capabilities streams. Second, it compares the respective cases for expanding AUKUS to include either Korea or Japan based on their relationships with the AUKUS countries. Third, it addresses how defense trade controls under AUKUS might affect ROK considerations about membership. Finally, it offers five options that ROK policymakers, but also other potential members, should consider in how to approach potential collaboration on Pillar 2, including ‘go hard and go early,’ ‘wait and see,’ ‘plug and play,’ ‘proposing Pillar 3,’ and ‘opting out.’ The Issue Brief concludes with some observations about how the re-election of President Donald Trump in the United States could create opportunities for naval shipbuilding cooperation in at least some parts of the AUKUS enterprise.

1. Understanding AUKUS Pillars 1 and 2

In 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic and Australia’s diplomatic and economic stand-off with China, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison and his closest advisors and ministers secretly negotiated with British Prime Minister Boris Johnson and U.S. President Joe Biden’s National Security Council on a trilateral partnership to help Australia acquire a fleet of nuclear-powered submarines. Announced to the world in September 2021, the AUKUS partnership marked the first time that the United States would transfer naval nuclear propulsion technology used to power the U.S. Navy’s attack submarines with another country since helping the United Kingdom in the late 1950s.

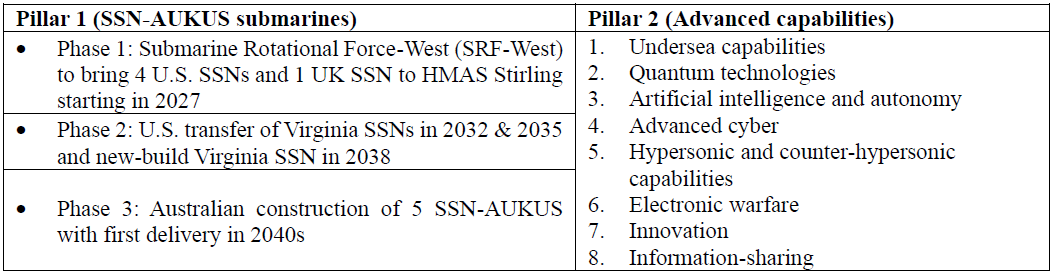

The announcement was followed by an 18-month consultation period between the three governments to determine the ‘optimal pathway’ for acquiring conventionally armed, nuclear-powered submarines (SSN), during which time two of the original three political architects were replaced as leaders. The optimal pathway concluded that Pillar 1 would proceed in several phases to build up Australia’s nuclear stewardship to receive and operate nuclear-powered submarines. The first phase would be known as Submarine Rotational Force-West (SRF-West) to bring four U.S. Virginia-class SSNs and one UK Astute-class SSN on rotational deployments to Australia beginning in 2027. The second phase would see the United States transfer to Australia at least three Virginia-class submarines beginning in 2032-33 at three-year intervals. The final phase would see Australia and the United Kingdom each build their own fleets of ‘SSN-AUKUS’-class submarines with the first delivery for Australia in the early 2040s.

Alongside this so-called Pillar 1, the three countries also agreed to cooperate on cutting-edge military technologies with relevance to undersea warfare and the objectives of nuclear-powered submarines to provide long-range deterrence and strike capabilities. These Pillar 2 capabilities would, over time, come to include six specific technology streams including undersea capabilities, quantum technologies, artificial intelligence and autonomy, advanced cyber, hypersonic and counter-hypersonic capabilities, electronic warfare, as well as cooperation on the innovation and information-sharing regimes necessary for their implementation across three distinct defense science and technology systems.3 Throughout 2022-23, the AUKUS countries conducted multiple pilot projects, including a joint exercise of undersea drones, contracts for quantum clocks for navigation and timing, AI-enabled swarm drones, a P-8 Poseidon aircraft maritime sonobuoy ISR test, and launched the AUKUS Defense Investor Network including 300 companies worth $265 billion.

Pillars 1 and 2 of the AUKUS enterprise ultimately seek to increase the collective military power of the three countries in the Indo-Pacific maritime theater to deter China’s rapidly growing naval capabilities. Unlike other minilateral partnerships such as the Quad which try to avoid overt military connotations, AUKUS is, by design, a defense industrial effort to build specific military capabilities. This is demonstrated by the leading role of the Australian Department of Defence in publishing the guiding policy documents that inform the strategy and implementation of both pillars of the AUKUS enterprise, including the 2023 Defense Strategic Review, 2023 Defense Industry Development Strategy, 2024 National Defense Strategy and Integrated Investment Plan, and 2024 Defense Innovation, Science and Technology Strategy. The U.S. and UK counterparts have similarly articulated the policy process for achieving the AUKUS enterprise.

Table 1. AUKUS Pillars 1 and 2

2. Expanding AUKUS Pillar 2

Throughout late 2023 and early 2024, the AUKUS countries began to note their desire to broaden cooperation on Pillar 2 capabilities with key allies and partners. At the AUKUS Defense Ministers’ Joint Statement in April 2024, the ministers outlined five criteria for consideration: technological innovation, financing, industrial strengths, ability to adequately protect sensitive data and information, and impact on promoting peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific region.4 On the third anniversary of AUKUS in September 2024, the AUKUS leaders further added, “Recognizing these countries’ close bilateral defense partnerships with each member of AUKUS, we are consulting with Canada, New Zealand, and the Republic of Korea to identify possibilities for collaboration on advanced capabilities under AUKUS Pillar 2.”5

ROK commentary has been rife with misinformation about what AUKUS is. Some have framed it as a purely civilian science and technology partnership, a defense industry export opportunity, or even a tool to deter North Korean military threats.6 ROK interest in collaborating with the AUKUS partnership, not to mention other minilateral partnerships, is subject to changing threat perceptions of China. Meanwhile, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs has condemned any expansion of AUKUS as “stoking bloc confrontation.”7 While the progressive-leaning Democratic Party has not given a position regarding collaboration with the AUKUS partnership, it will likely be more cautious and sensitive to this impression. Meanwhile, the Yoon administration’s interest in Pillar 2 is part of a wider effort to re-engage nascent minilateral partnerships.8

The AUKUS debate thus parallels similar discussions in the ROK about the merits of participating in other U.S.-led minilaterals, such as the Five Eyes intelligence sharing partnership, the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, and the Camp David ROK-U.S.-Japan security partnership. Former Minister of Defense Shin Won-sik stated during the ROK-Australia 2+2 Foreign and Defense Ministers’ Meeting on May 2024, “The Korean government, to enhance the regional peace, we support the AUKUS Pillar 2 activities,” adding that “Korea’s defense science and technology capabilities will contribute to the peace and stability of the development of AUKUS Pillar 2 and the regional peace.”9

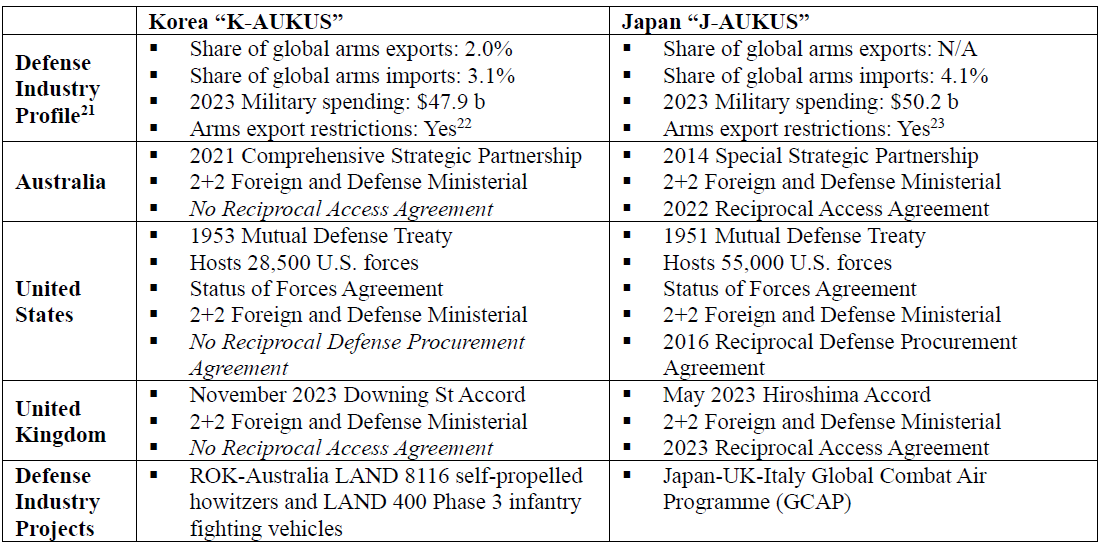

3. KAUKUS vs. JAUKUS: Unpacking Relations

This section compares the relative merits of the ROK and Japan’s potential to join an expanded AUKUS Pillar 2 partnership. It focuses on the three bilateral relationships that will underpin any collective cooperation, with Australia, the United States, and the United Kingdom. First, Japan is widely considered the frontrunner candidate for any expansion of AUKUS.10 The White House released a joint statement stating that “AUKUS partners and Japan are exploring opportunities to improve interoperability of their maritime autonomous systems as an initial area of cooperation.”11 U.S.-Japan defense industry cooperation is being upgraded since the signing of a Reciprocal Defense Procurement agreement (RDP) in 2016 and Japan is now able to facilitate co-development and co-production of advanced missiles, missile defense, and U.S. naval maintenance, repair, and overhaul (MRO) support.

Japan is also a strategic partner of Australia through the Australia-Japan Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation of 2007 and the Special Strategic Partnership (SSP) established in 2014.12 Also, the Australia-Japan Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA) was signed in January 2022 to further promote bilateral security and defense cooperation. This agreement was Japan’s first such treaty aside from with the United States.13 Japan and the United Kingdom are also close partners, most recently signing the Hiroshima Accord in 2023, defined by both countries as “an enhanced UK-Japan global strategic partnership.”14 The two countries also signed an RAA in 2023.15 Australia, the United States, and Japan started the Trilateral Strategic Dialogue (TSD) in 2002, which first began at the level of senior officials, but is now elevated to the level of foreign ministers.

On the other hand, the ROK’s relationship with the AUKUS countries has been more uneven compared to Japan. Building on the momentum of the 2023 Washington Declaration and Camp David Summit, the ROK-U.S. Defense Vision outlined a way forward for the security and defense of the two countries and they affirmed to play a more active role in contributing to regional security.16 Yet despite significant effort by the Yoon administration to upgrade defense industry cooperation with the United States, including signing a Security of Supply Arrangement (SOSA) in late 2023, the two countries have not yet signed an RDP due to U.S. Congressional pushback.17 At the 2024 ROK-U.S. Security Consultative Meeting (SCM) in October 2024, the two countries agreed to establish a vice-minister level defense science and technology executive committee to “explore the application of cutting-edge science and technology in the defense sector, as well as cooperation on AUKUS Pillar 2.”18Meanwhile, ROK-Australia relations have increased significantly since the 2021 Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (CSP) was announced.19 Bilateral defense industry cooperation has also begun with acquisitions for self-propelled howitzers and infantry fighting vehicles. Relations between the ROK and the United Kingdom were strengthened through signing the Downing Street Accord in 2023, becoming a ‘global strategic partnership’ and agreed to launch a 2+2 ministerial meeting on foreign affairs and defense.20

The comparison between South Korea and Japan’s relations with the AUKUS countries is outlined in Table 2. What it demonstrates is that the scope of South Korea’s security cooperation with Australia and the United Kingdom continues to lag behind that of Japan. This partly explains why the AUKUS partnership as a collective has been keener to consider Japan as an initial partner. However, it also shows that there are opportunities for ROK officials to upgrade and fill in the gaps, something that the Yoon administration has made a clear priority.

Table 2. ROK and Japan Relations with AUKUS Countries

4. Defense Trade Control Considerations

Arguably the most important outcome of AUKUS over the past three years has not been in producing a military capability to deter China, but rather the transformation of the defense export control regime among the three countries. There has been enormous progress in the AUKUS enterprise streamlining the three countries’ defense trade controls and export control regimes. Despite their longstanding military cooperation as part of the Five Eyes intelligence sharing partnership and membership in the U.S. National Technology and Industrial Base (NTIB), many Australian experts and officials had long been frustrated by the onerous restrictions on closer defense industrial cooperation and integration.

In the months following the AUKUS announcements, legislatures in all three countries moved to reform export control policies. The 2024 U.S. Congress National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) legalized Australian MRO of U.S. SSNs, Australian workforce training in the United States, and wide-ranging reforms to defense trade controls. Together, these initiatives are expected to result in license-free trade for 70 percent of defense exports from the United States to Australia, and over 80 percent from Australia to the United States.24 Also, the U.S. Department of State published an interim final rule to amend the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) and implemented an export licensing exemption for Australia and the United Kingdom, which became effective from September 1, 2024.25

In the coming years, Pillar 2 cooperation will produce common military technologies only shared among the AUKUS countries. There will be onerous data and information security protections and strict controls over any proliferation or export, let alone commercial sale, of such capabilities. Any decision by Korea to join AUKUS must therefore carefully consider how it might affect its own defense industrial export ambitions. At the same time, if the ROK’s ultimate goal is closer integration in the emerging common defense industrial ecosystem led by the United States, then AUKUS reforms offer a valuable learning model. Many ROK defense firms have long sought to break into the large U.S. and so-called Five Eyes defense market given their own longstanding sharing of technologies and integrated supply chains.26 The ROK-U.S. alliance itself is responding to these cues. For example, the 23rd ROK-U.S. Integrated Defense Dialogue emphasized “strengthening the connection between U.S. and ROK defense industrial bases to enhance interoperability and interchangeability within the Alliance defense architecture.”27

5. Five Options for ROK Consideration

Whether or not South Korea is ultimately invited to join the AUKUS partnership is a matter for the governments of Australia, the United States, and the United Kingdom. Rather, this Issue Brief has outlined the trajectory of this trilateral partnership to enable ROK officials to better weigh the potential benefits and costs of membership. Should such an invitation be extended to Seoul, the ROK can then consider how it might respond. This Issue Brief concludes by examining five options, including ‘go hard and go early,’ ‘wait and see,’ the ‘plug and play’ approach, building a ‘Pillar 3’ line of effort, and staying out. These options also apply to the other prospective member countries of Japan, Canada, New Zealand, and potentially others in the near future.

Option 1 is to ‘go hard and go early.’ Being a latecomer to minilateral partnerships has been a recurring challenge for ROK foreign policy.28 The most obvious example of this has been ROK engagement with the Quad, which Seoul declined to join out of fear of antagonizing China, only to later express interest in joining the partnership after it had developed a complex bureaucratic architecture.29 In the case of AUKUS, the ROK can be a first mover to shape the agenda from within and it could participate in the still early stages of Pillar 2 cooperation. The risk of such a strategy would, however, be that the ROK would need to be able to credibly offer something of value to the AUKUS partnership that is not already possessed.

Option 2 would be to take a ‘wait and see’ approach that adopts strategic patience to join at the last possible moment when there has been significant progress across some or all of the Pillar 2 capabilities of interest to ROK defense scientists. The risk of such a strategy would be that trying to join at such a late stage would require major regulatory reforms and legal changes that the AUKUS countries had spent many years implementing. As such, the entry costs would grow over time.

Option 3 would be to take a ‘plug and play’ approach that sought to isolate cooperation in specific Pillar 2 streams, such as joining information-sharing, quantum, and cyber while negotiating ‘K-defense’ carveouts for hypersonics, undersea drones, and AI and autonomy where ROK companies may have commercial export ambitions. This would preserve the defense industry export angle while offering cooperation on a case-by-case basis. For example, the ROK and AUKUS countries could trial start a test on P-8A Poseidon aircraft ISR information-sharing recently conducted since the ROK Navy recently acquired its fleet of six P-8A Poseidon aircraft. The risk of such a strategy is that, given the preceding discussion of defense trade controls, it remains unclear if emerging Pillar 2 streams can be siloed for legal purposes.

Option 4 would be to pursue what some experts have called ‘Pillar 3’ cooperation on existing military capabilities in short supply.30 For example, the ROK could work with AUKUS and non-AUKUS partners to scale up co-production of munitions and weapons systems, which the United States is struggling to replace, such as 155 mm artillery shells, Stinger anti-aircraft systems, Javelin anti-armor systems, and multiple launch rocket systems.31 The ROK’s recent arms deals to ‘backfill’ European arsenals could be expanded into a wider initiative that combines commercial and strategic partnerships with the AUKUS countries.32 This would allow the ROK to cooperate with the AUKUS countries while avoiding much of the complex legal and export control changes occurring in Pillars 1 and 2.

Finally, option 5 would be ‘opt-out’ and decline any invitation for defense industrial cooperation. In doing so, the ROK can preserve its ‘K-defense’ export agenda, not antagonize China in terms of strategic signaling, avoid any perceived competition with Japan, and potentially even develop its own Pillar 1 SSN pathway independently. It could also pursue civilian, non-military science and technology cooperation such as on drones and AI through alternative minilateral partnerships. The risk of such a strategy would be that the ROK is eventually relegated to a different tier of alliance cooperation.

Conclusion

This Asan Issue Brief has examined the case for whether Korea should join the AUKUS Pillar 2 partnership. For U.S. allies looking to join the AUKUS enterprise or build similar arrangements of their own, there are important lessons in terms of how to design the ‘optimal pathway’ to be suitably favorable to the United States and earn its trust and support. Yet, in many respects, the Pillar 2 debate sidesteps the bigger question about why the United States has chosen to share its naval nuclear propulsion technology with Australia in a ‘one-off’ deal. It is worth recalling that when the AUKUS partnership was first announced in 2021, prominent Korean experts lamented that the United States had long resisted any such arrangement with the ROK.33 In the years to come, as North Korea, China, and Russia’s nuclear-powered and nuclear-armed submarine capabilities increase, the U.S. position may change, as already hinted by senior U.S. military commanders.34

In the meantime, the expansion of AUKUS Pillar 2 represents an important new phase in strengthening defense industrial collaboration between the United States, Australia, the United Kingdom, and U.S. allies and partners. Option 1 (‘go hard and go early’) or Option 3 (‘plug and play’) should be the foremost considerations based on an assessment of ROK defense science and technology strengths and weaknesses across the Pillar 2 capabilities. Option 4 (‘Pillar 3’) should be actively pursued regardless of whether the ROK ultimately joins the AUKUS partnership. Options 2 (‘wait and see’) and 5 (‘opt-out’) should be considered if there is no possibility of building and maintaining bipartisan support for cooperation and efforts should then be focused on purely bilateral alliance defense science and technology cooperation with the United States exclusively to deal with North Korean military technologies.

The re-election of President Trump to the White House adds a new variable to the AUKUS debate. There is a strong case to suggest that the AUKUS arrangement as envisioned over the next four years is sufficiently favorable to the Trump administration for it to continue the partnership. Australia will transfer $3 billion investment directly to the United States over the next three years to support the U.S. submarine industrial base. The United States will begin to forward deploy its Virginia-class attack submarines to Australia’s naval facilities in 2027, the third year of his term. And the crucial date for the transfer of the first Virginia-class submarine will only take place after he leaves office so he is unlikely to concern him. It remains to be seen whether President Trump and his advisors will judge the current financial and industrial integration arrangements as benefitting the United States, but the near-term outlook is good. President Trump has focused on greater ROK-U.S. troop cost-sharing and tariff policy re-balancing but he has also expressed a desire to cooperate with the ROK on shipbuilding. This suggests that there is scope for closer defense industrial cooperation in at least some parts of the AUKUS enterprise.35

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 1. Peter K. Lee and Alice Nason, “365 Days of AUKUS: Progress, challenges and prospects,” United States Studies Centre (September 12, 2022), https://www.ussc.edu.au/analysis/365-days-of-aukus-progress-challenges-and-prospects.

- 2. The White House, “Joint Leaders Statement to Mark the Third Anniversary of AUKUS” (September 17, 2024), https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2024/09/17/joint-leaders-statement-to-mark-the-third-anniversary-of-aukus/.

- 3. Luke A. Nicastro, “AUKUS Pillar 2 (Advanced Capabilities): Background and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service (May 21, 2024), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47599.

- 4. United Kingdom Ministry of Defence, “AUKUS defence ministers joint statement: April 2024” (April 8, 2024), https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/aukus-defence-ministers-joint-statement-april-2024.

- 5. The White House, “Joint Leaders Statement to Mark the Third Anniversary of AUKUS” (September 17, 2024), https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2024/09/17/joint-leaders-statement-to-mark-the-third-anniversary-of-aukus/.

- 6. Lee Jung-gu and Lee Jae-eun, “Potential AUKUS partnership boosts South Korea’s defense industry prospects,” The Chosun Ilbo (April 12, 2024), https://www.chosun.com/english/industry-en/2024/04/12/PVLBYXEM7RFWRCNDR75JJOZWJ4/; Kwak Yeon-soo, “Will S. Korea join AUKUS Pillar 2 in face of deepening Russia-NK ties?” The Korea Times (July 13, 2024), https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2024/10/113_378490.html.

- 7. “Editorial: AUKUS expansion an alarming move destabilizing region: experts,” Global Times (April 8, 2024), https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202404/1310227.

- 8. Yoon Suk Yeol, “South Korea Needs to Step Up,” Foreign Affairs (February 8, 2022).

- 9. Australian Government, “Press Conference, Melbourne” (May 1, 2024), https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/transcripts/2024-05-01/press-conference-melbourne>

- 10. The White House, “United States-Japan Joint Leaders’ Statement” (April 10, 2024), https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2024/04/10/united-states-japan-joint-leaders-statement/

- 11. The White House, “Joint Leaders Statement to Mark the Third Anniversary of AUKUS” (September 17, 2024), https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2024/09/17/joint-leaders-statement-to-mark-the-third-anniversary-of-aukus/

- 12. Australian Government, “Australia-Japan Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation” (October 22, 2022), https://www.dfat.gov.au/countries/japan/australia-japan-joint-declaration-security-cooperation

- 13. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “Japan-Australia Reciprocal Access Agreement” (January 6, 2022), https://www.mofa.go.jp/a_o/ocn/au/page4e_001195.html; Australian Government, “Australia-Japan Reciprocal Access Agreement,” https://www.defence.gov.au/defence-activities/programs-initiatives/australia-japan-reciprocal-access-agreement

- 14. The United Kingdom Government, “The Hiroshima Accord: An Enhanced UK-Japan Global Strategic Partnership” (May 18, 2023), https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/64662b0b0b72d30013344777/The_Hiroshima_Accord.pdf

- 15. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “Signing of Japan-UK Reciprocal Access Agreement” (January 11, 2023), https://www.mofa.go.jp/erp/we/gb/page1e_000556.html

- 16. U.S. Department of Defense, “Defense Vision of the U.S.-ROK Alliance” (November 13, 2023), https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3586528/

- 17. Peter K. Lee and Heesu Lee, “Reciprocating Trust and Reconciling Ambitions in ROK-U.S. Defense Industrial Cooperation,” Asan Issue Brief 2024-03 (May 28, 2024), https://en.asaninst.org/contents/reciprocating-trust-and-reconciling-ambitions-in-rok-u-s-defense-industrial-cooperation/.

- 18. Ashley Roque and Aaron Mehta, “South Korea eyes pathway for AUKUS Pillar II with new defense tech agreement,” Breaking Defense (October 30, 2024), https://breakingdefense.com/2024/10/south-korea-eyes-pathway-for-aukus-pillar-ii-with-new-defense-tech-agreement/.

- 19. Australian Government, “Australia-Republic of Korea Comprehensive Strategic Partnership” (December 11, 2021), https://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/republic-of-korea/republic-korea-south-korea/australia-republic-korea-comprehensive-strategic-partnership

- 20. The United Kingdom Government, “The Downing Street Accord: A United Kingdom-Republic of Korea Global Strategic Partnership” (November 22, 2023), https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/655e58f602e2e1000d433691/November_2023_-_The_Downing_Street_Accord__A_United_Kingdom-Republic_of_Korea_Global_Strategic_Partnership.pdf

- 21. Nan Tian, Diego Lopes da Silva, Xiao Liang, Lorenzo Scarazzato, “Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2023,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (April 2024), https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2024-04/2404_fs_milex_2023.pdf; Pieter D. Wezeman, Katarina Djokic, Mathew George, Zain Hussain and Siemon T. Wezeman, “Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2023,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (March 2024), https://www.sipri.org/publications/2024/sipri-fact-sheets/trends-international-arms-transfers-2023.

- 22. Government of the Republic of Korea, Article 19 (Public Notice of Strategic Items and Export Permission Therefor), “Foreign Trade Act,” https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_mobile/viewer.do?hseq=60912&type=part&key=28, and Chapter VII (Supplementary Provisions) Article 68 (Permission for Exportation), “Enforcement Decree of the Defense Acquisition Program,” https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_mobile/viewer.do?hseq=67624&type=part&key=13.

- 23. Government of Japan, “The Three Principles on Transfer of Defense Equipment and Technology,” https://www.mofa.go.jp/fp/nsp/page1we_000083.html

- 24. William Greenwalt, Tom Corben, “AUKUS enablers? Assessing defence trade control reforms in Australia and the United States,” United States Studies Centre (August 21, 2024), https://www.ussc.edu.au/aukus-assessing-defence-trade-control-reforms-in-australia-and-the-united-states

- 25. U.S. Department of State, “AUKUS Defense Trade Integration Determination” (August 15, 2024), https://www.state.gov/aukus-defense-trade-integration-determination/

- 26. Lee Jung-gu, Lee Jae-eun, “Potential AUKUS partnership boosts South Korea’s defense industry prospects,” The Chosun Ilbo (April 12, 2024), https://www.chosun.com/english/industry-en/2024/04/12/PVLBYXEM7RFWRCNDR75JJOZWJ4/

- 27. U.S. Department of Defense, “Joint Press Statement for the 23rd Korea-U.S. Integrated Defense Dialogue” (September 18, 2023), https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3528305/

- 28. Peter K. Lee, “More Than a ‘Plus One’”: Korea’s Minilateral Imperative,” Korea On Point, The Sejong Institute (June 30, 2022), https://koreaonpoint.org/view.php?topic_idx=33&idx=99.

- 29. Chung Kuyoun, “South Korea’s Perspective on Quad Plus and Evolving Indo-Pacific Security Architecture,” Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs (2020); Peter K. Lee and Chungku Kang, “South Korea’s Quad Opportunity: Aligning Foreign Policy and Public Opinion,” Asan Issue Brief 2023-03 (November 15, 2023), https://en.asaninst.org/contents/south-koreas-quad-opportunity-aligning-foreign-policy-and-public-opinion/.

- 30. William Greenwalt and Tom Corben, “Breaking the barriers: Reforming US export controls to realise the potential of AUKUS,” United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney, May 2023, p. 30, https://www.ussc.edu.au/breaking-the-barriers-reforming-us-export-controls-to-realise-the-potential-of-aukus.

- 31. Seth G. Jones, “Empty Bins in a Wartime Environment: The Challenge to the U.S. Defense Industrial Base,” Center for Strategic and International Studies (January 23, 2023), https://www.csis.org/analysis/empty-bins-wartime-environment-challenge-us-defense-industrial-base.

- 32. Peter K. Lee, “The K-Arsenal and Strategic Clarity,” Korea On Point (November 29, 2023); Peter K. Lee and Tom Corben, “A K-Arsenal of Democracy? South Korea and U.S. Allied Defense Procurement,” War on the Rocks (August 15, 2022), https://warontherocks.com/2022/08/a-k-arsenal-of-democracy-south-korea-and-u-s-allied-defense-procurement/.

- 33. Moon Chung-in, “The Four Shadows Cast by AUKUS,” Hankyoreh (October 11, 2021), https://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/english_editorials/1014675.html.

- 34. Lee Hyo-jin, “Is US shifting stance on S. Korea’s acquisition of nuclear submarines?” The Korea Times (July 15, 2024), https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2024/11/113_378696.html.

- 35. Peter K. Lee, Chungku Kang, Heesu Lee, “The 2024 U.S. Elections and Outlook for U.S. Allies,” Asan Issue Brief 2024-07 (November 19, 2024), https://en.asaninst.org/contents/the-2024-u-s-elections-and-outlook-for-u-s-allies/.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter