South Korea is currently facing the highest nuclear threat in the world. This might not be a universal perception, but it is what many Korean people believe. North Korea’s “Law on the DPRK’s Policy on Nuclear Forces,” announced in September 2022, outlined a new nuclear doctrine that pledges to use (tactical) nuclear weapons once war breaks out, or even preemptively in some cases, making it essentially the most aggressive nuclear doctrine in history. To prove that these were not empty threats, North Korea conducted a military drill for its “tactical nuclear operation units”

Under these kinds of threats, South Koreans are seriously asking, can extended deterrence still work? Even the South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol raised the possibility of the Republic of Korea (ROK or South Korea) building its own nuclear weapons in response. US strategists need to understand these concerns as well as the limits of extended deterrence and prepare for potential alternative futures.

An Uneven Playing Field

In 2022, North Korea launched more than 90 missiles—the highest-ever number of launches within a year. However, responses from the ROK under President Yoon have been relatively mild compared to the scale of North korea’s actions. The lack of any kind of inter-Korean talks since 2019 led South Korea to revive and conduct a series of US-ROK large-scale, live-fire joint military exercises, which had been downsized since 2018 in favor of peace talks under the previous Moon Jae-in administration. Additional drills were added as North Korea started to conduct its own operational, live-fire drills. When one of North Korea’s missiles crossed the Northern Limit Line (NLL) toward South Korean territorial waters last November, South Korea’s response was a proportional launch of a South Korean missile into North Korean territorial waters only as far as the original missile had reached. In late December, when a North Korean unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) invaded the skies above Seoul, South Korea launched its drones to the border to remind North Korea of the violation of the Armistice Agreement and to warn it to stop provocations.

Historically, the military confrontations between the two Koreas have never been fair. North Korea consistently violates international rules and norms to try to gain a military advantage over the South, whereas South Korea upholds international rules and norms, limiting how it responds to increasingly provocative DPRK actions. North Korea has rarely apologized for its provocations, except for when South Korea and the US brought up their overwhelming military forces to its nose. Essentially, South Korea “loses” precious lives of its soldiers and even civilians in extreme cases by complying with international order, while North Korea “gains” its victory in internal politics by violating international laws. Nonetheless, North Korea still criticizes South Korea for creating a “강대강” (strong vs. strong) confrontation even when it responds with moderation.

Furthermore, North Korea has consistently violated the United Nations Security Council resolutions and continued developing its nuclear weapons program. Meanwhile, South Korea has made many concessions over the years to encourage a denuclearization process. For instance, US-ROK joint military exercises have been suspended at times or downsized to simulations and tabletop exercises; special considerations were made for North Korea to compete in the 2018 PyeongChang Olympics; and aid and economic projects have been offered to try to improve inter-Korean relations. But even former President Moon Jae-in’s peace initiative in 2018 failed to bring about sustainable progress toward the North’s denuclearization. And past negotiations—whether multilateral talks, such as the Six Party Talks; trilateral talks between South Korea, North Korea and the US; and bilateral talks, such as inter-Korean talks and US-DPRK talks, have failed as well. Even

Changes in South Korean Threat Perceptions

In South Korea, there are two starkly contrasting political views on North Korean denuclearization. One is that North Korea’s nuclearization is intended for negotiations with the international community (especially the United States), and so denuclearization is actually possible. At his 2021 New Year’s press conference, then-President Moon Jae-in said he believed Chairman Kim Jong Un clearly had “a will for peace, for dialogue, and for denuclearization.” The other viewpoint is that since nuclear weapons have become the basis for the existence of the regime, denuclearization is impossible, thereby rendering any dialogue pointless. Former Foreign Minister Song Min-soon, who led the Six Party Talks under the progressive Roh Moo-hyun government, once argued that North Korea, which has “already become the world’s ninth nuclear power,” had no will to denuclearize and that South Korea should make new attempts in responding to North Korea’s nuclear program. Regardless of what South Koreans think, however, Kim Jong Un has made it abundantly clear that he will never give up nuclear weapons.

Public opinion is also divided as to which is the key country for North Korea’s denuclearization. At one time, there was a belief in South Korea that China was the key because Chinese support is fundamental to North Korea’s ability to maintain its regime and continue development of nuclear weapons despite international sanctions. However, these expectations have been lowered as the country suffered repeated failures in the Six Party Talks and Chinese pressure on South Korea against its Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) deployment.

There have also been some misunderstandings about North Korea’s nuclear armament. First, there is one school of thought in South Korea that North Korea’s nuclear weapons will ultimately become the property of South Korea upon unification. Some reports even pointed out that unification would make “Unified Korea” a nuclear-weapon state. This is a product of nationalistic romanticism that views neighboring countries, such as China, Japan and Russia, as threats. That said, the number of people who ascribe to such thinking is steadily decreasing.

There is another view in South Korea that even though North Korea has nuclear weapons, it does not intend to use them against South Korea. In September 2017, then-President Moon Jae-in denounced North Korean nuclear development as simply a means to negotiations during an interview with CNN. However, this belief is also fading, as North Korea is already conducting exercises to strike various targets in South Korea with tactical nuclear weapons.

Ultimately, these perception changes are forcing South Korea to think more seriously about the nature of the threat North Korea poses and bolster the ways and means to respond to DPRK nuclear threats. Consequently, successive ROK administrations have been trying to realize the ambitious plan of building an ironclad defense against North Korean nuclear weapons by strengthening both US extended deterrence and the ROK’s advanced conventional forces.

Changing the Stance

North Korea increased the intensity of its nuclear threats against South Korea when President Yoon was elected in 2022. Yoon is a political rookie who became the opposition party’s presidential candidate after serving as prosecutor general in the previous administration. As such, few expected him to possess an elaborate philosophy of governance or a detailed view of international politics. Instead, during his campaign, he emphasized common sense and, as a former prosecutor, emphasized upholding the rule of law.

Political opponents have labeled Yoon as the “Korean Trump” and implied that his election would lead to war with North Korea. The core of Yoon’s North Korean policy is that of a principled response. If North Korea changes its direction and reengages in dialogue, South Korea will provide maximum support (ala his “audacious initiative”). However, if North Korea continues to make threats and offensives, South Korea will stand against such actions. Yoon has presented himself as an ardent believer in extended deterrence when it comes to deterring North Korea’s nuclear use. During his candidacy, Yoon opposed the redeployment of nuclear weapons in Korea and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)-style nuclear sharing and reiterated that he would work to strengthen US-ROK cooperation while adhering to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) regime.

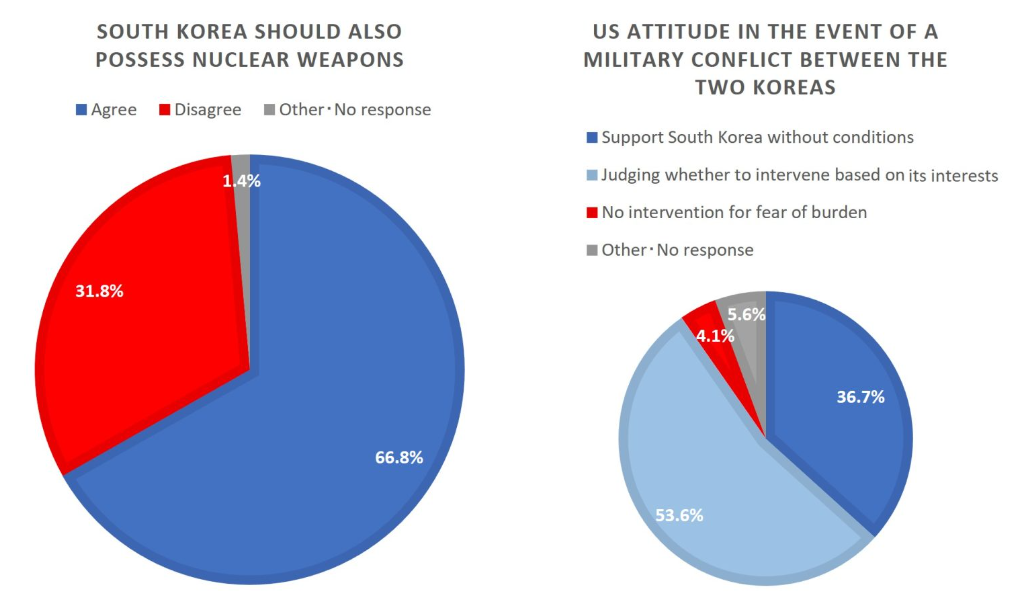

However, as North Korea’s provocations intensify in tactics and frequency, and its rhetoric threatens nuclear war, Yoon’s views are also changing, as are the opinions of the South Korean people. According to a poll by Hankook Ilbo in January 2023, 66.8 percent of the South Koreans surveyed supported the ROK’s nuclear armament, while only 31.8 percent opposed it. In addition, only 36.7 percent of respondents believed that the US would intervene in a military conflict between the North and the South, while 53.6 percent said that the US would determine whether or not to intervene based on its own interests.

Figure 1. Results of a January 2023 Hankook Ilbo poll of South Korean citizens on ROK nuclear weapons and US military intervention.

Source: Moonjoong Kim, “70 Years of Korea-US Alliance Public Opinion Survey,” Hankook Ilbo, https://www.hankookilbo.com/News/Read/A2022122712090002350, January 2, 2023. (Translated by Uk Yang.)

The Yoon administration has put forth strengthening extended deterrence as the best countermeasure to the North’s growing WMD capabilities. But the South Korean public’s faith in the US commitment continues to be called into question, pointing to such realities as the long-delayed modernization of US nuclear forces, as well as past US behaviors, such as when former US President Donald Trump frequently threatened to withdraw US troops from South Korea, the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, and the measured US response to the war in Ukraine. There are also questions about the level of US-ROK joint planning and joint execution of extended deterrence operations. President Yoon recently announced that joint US-ROK nuclear exercises would be held, but when President Biden was subsequently asked whether this was true, he responded simply, “No.” This discrepancy ignited controversy and has more and more South Koreans wondering whether, in the case of a crisis on the Korean Peninsula, the United States would risk New York for Seoul.

Is South Korea Going Nuclear?

On January 11, 2023, President Yoon delivered his New Year’s Policy Briefing on Foreign Affairs and National Defense, where he was reported to have raised the possibility of South Korea’s nuclear armament. However, his words on this subject were:

As North Korea’s nuclear threat becomes more serious, we may deploy tactical nuclear weapons in South Korea or possess our own nuclear weapons. If so, it will not take a long time, and we will be able to have it very shortly with our advanced science and technology. However, it is always important to choose a means that is realistically suitable.

…Currently, joint planning and joint execution between Korea and the United States are being discussed. This is not a concept in which the US provides unilateral protection to Korea, but an approach in which mutual interests are exactly aligned. (Translation by author.)

This was the first time that the president of the Republic of Korea had ever mentioned the specific words of tactical nuclear deployment or nuclear armament, so it has been broadly overstated by the media. However, a careful read of President Yoon’s remarks shows that he was not actually signaling that South Korea was going to pursue nuclear weapons. Rather, he presented this alternative path as a way to emphasize the need for strengthening extended deterrence and raising it to the level of joint planning and execution.

At the same time, this statement was notable. In the past, no matter how much the nuclear threat escalated, the South Korean president could not dare to mention the “n-words,” such as “nuclear weapon deployment” or “nuclear armament.” This is clearly no longer the case. But this shift is not simply a message to the DPRK about the ROK’s convictions. It also conveys to the US a long-held frustration about the lack of transparency in US decision making about the potential use (or non-use) of nuclear weapons on the Korean Peninsula on behalf of South Korea. While the US will always retain sole authority over the use of US nuclear weapons, South Koreans are becoming more desperate and determined to play some role in planning and operations.

Conclusion

South Korea is not going nuclear today or tomorrow as long as the US extended deterrence commitment prevails and can adapt to the changing geopolitical landscape. That said, the situation is evolving. China could possess more than 1,000 nuclear warheads by 2030, while North Korea continues to produce fissile material to increase its nuclear arsenals. In such a scenario, the US may need assistance maintaining even a minimum nuclear deterrent posture in the Indo-Pacific, for which South Korea’s nuclear armament could be beneficial. That said, South Korea would go nuclear only when the US strongly supports it or when the 70-year-old US-ROK alliance is broken. Otherwise, there’s no defensible reason for South Korea to go against the international nonproliferation regime.

* The view expressed herein was published on February 3 in 38 North and does not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter