One of the most controversial issues in the run up to the 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympics was the formation of an inter-Korean women’s ice hockey team. The idea of an inter-Korean team had often been discussed between the two Koreas during past Olympics, but it had always fallen through. The Moon administration viewed the unified team as the perfect opportunity to deescalate tension on the Korean Peninsula, while marketing the games as the “Peace Olympics.” On January 17, South and North Korean negotiators pushed the idea through during a vice-ministerial level dialogue and agreed to compete together in women’s ice hockey.

However, the reaction of South Koreans to the decision was completely different than what the Moon administration expected. While many welcomed North Korea’s participation in the Winter Olympics, the formation of the unified hockey team triggered a strong backlash in South Korea.1 According to a poll conducted by Seoul Broadcasting System (SBS) and the Office of the Speaker of the National Assembly in January 2018, 81.2% said they welcomed North Korea’s participation in the Olympics, but 72.2% answered that the government should not have forced the formation of a unified women’s hockey team.2 Criticism against the decision was particularly strong among the younger generation and analysts speculated that the unified team controversy would lead to a decline in support for President Moon.

The unified team controversy has raised significant interest in the perception of North Korea and unification amongst South Korea’s young generation. Using data from the Asan Institute’s public opinion surveys, this Issue Brief investigates South Koreans’ perceptions of North Korea, economic assistance, and unification. Particularly, we analyze the similarities and differences between the newly emerging security conservatives in their 20s and the traditional security conservatives in their 60s and over.

Perceptions of the North Korean Threat

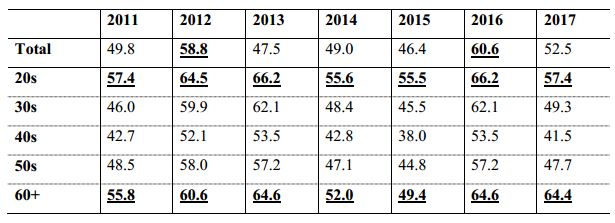

South Koreans’ perception of the North Korean threat directly affects their perception of North Korea and unification. In order to examine the perception of the North Korean threat, we analyzed South Koreans’ evaluations of the possibility of a war breaking out on the Korean Peninsula. Although no significant changes in perception took place over the past seven years, breakdown by age cohorts tells a more interesting story.

Compared to other age groups, a much higher percentage among those in their 20s and the elderly believed a war between the two Koreas could break out. Each year, the 20s consistently recorded the highest rates, followed by the 60+, with an exception in 2017. Throughout 2011 to 2017, at least 55.5% of South Koreans in their 20s believed that another war could break out on the Korean Peninsula [min=55.5% (2015), max=66.2% (2013, 2016)]. These results throughout the years confirmed that the two age groups perceived the North Korean threat much more seriously than other age groups and also explain their conservative tendencies regarding security issues.

Table 1. Likelihood of War on the Korean Peninsula by Age3(%)

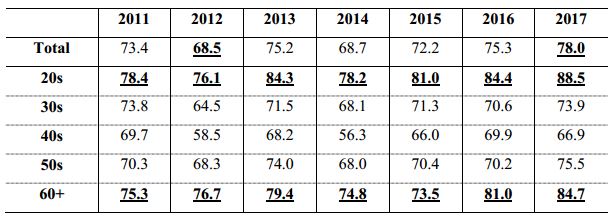

Attitudes on Aid

Economic and humanitarian aid has always been a subject of debate. Some have argued that South Korea should provide economic assistance to North Korea for humanitarian purposes. Others have strongly opposed it, arguing that it would only help North Korea develop its nuclear capabilities. Table 2 shows that the vast majority of South Koreans have continuously opposed providing economic aid to North Korea during the past 7 years. In 2012, 68.5% stated that South Korea should not provide economic assistance unless there is a significant change in “attitude” by North Korea.4 That number jumped to a record high of 78% in 2017.5 In the same year, only 22% of respondents answered that South Korea should provide economic assistance regardless of inter-Korean relations. Even in 2012, when the rates were at its highest, only 31.5% said South Korea should provide aid.

Generally, negative opinions prevailed in all ages but were significantly stronger among those in their 20s and the elderly (high 70-80%) than those of other age groups (high 50-70%). The most recent data in 2017 shows just how much more the 20s (88.5%) strongly felt about not providing aid to North Korea compared to the 30s (73.9%) and 40s (66.9%).

Another important point is that the number of respondents in their 20s that have opposed providing economic aid to North Korea has continuously risen since 2011. Those who negatively viewed providing economic aid to North Korea in their 20s increased by 10.1% points since 2011 (2011= 78.4%, 2017=88.5%). As expected, the next biggest increase came from those in their 60s and older (9.4% p).

Table 2. Negative Attitude toward North Korean Economic Aid by Age6 (%)

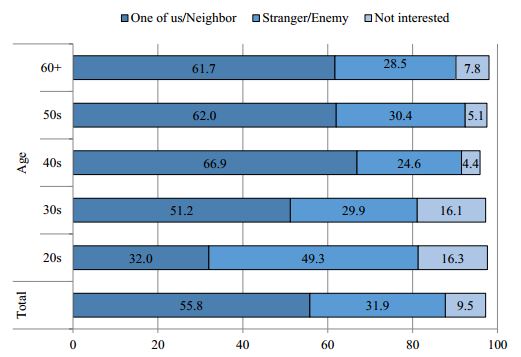

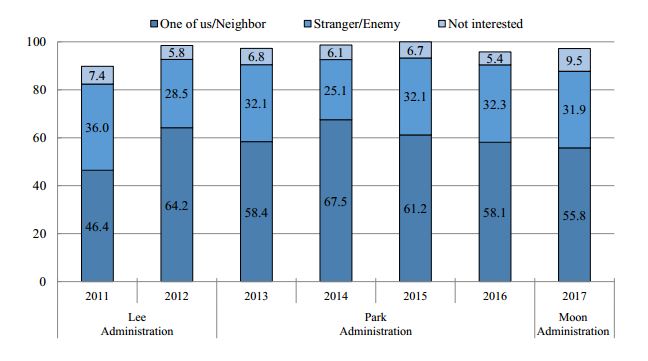

Perception of North Korea

South Koreans’ perception of North Korea has not shown significant change over the past eight years. Despite the numerous provocations of North Korea throughout the past decade, a majority of South Koreans still view North Korea as either “one of us” or “neighbor.” On the other hand, the number of South Koreans who view North Korea in a negative light has consistently been around 30% since 2012 (see Figure 1). Interestingly, despite the consistent headlines North Korea made in 2017, those that have said they are not interested in North Korea nearly doubled from the previous year (2016=5.4%, 2017=9.5%). It seems that the South Korean public is going through “North Korea fatigue” caused by the constant provocations in 2017.

Figure 1. Perception of North Korea7 (%)

Another noteworthy point is that although both the 20s and the elderly shared similar views on North Korea’s threat and economic aid, the two had very different perceptions of North Korea (see Figure 2). Breakdown by age groups shows that the 20s are the most hostile and indifferent towards North Korea. In 2017, almost half of the respondents in their 20s (49.3%) considered North Korea as either a “stranger” or an “enemy.” Only 30% responded as such in all other age groups.8 Additionally, while only 32% of those in their 20s considered North Korea as either “one of us” or “neighbor,” the elderly response was almost double (61.7%).

Figure 2. Perception of North Korea by Age9 (%)

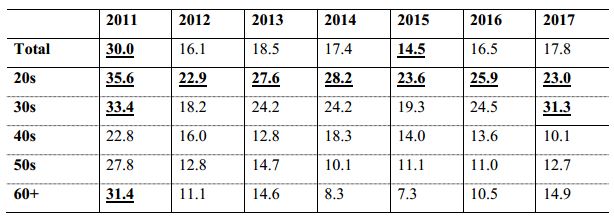

Attitude toward Unification

One of the most important issues in inter-Korean relations is undoubtedly unification. Since 2010, a growing number of South Koreans have expressed an interest in unification. While the numbers were steeply down due to the sinking of the Cheonan and the shelling of Yeonpyeong Island in 2010 (52.6%), it quickly increased to 70% the very next year. Since 2012, the rate has remained in the 80% range (2012=83.9%, 2013=81.5%, 2014=82.6%, 2015=85.5%, 2016=83.5%), 2017= 82.3%).

However, age cohort breakdowns show a very different story. The lower the age group, the more indifferent they are to unification. From 2011-2017, about 25% of South Koreans in their 20s admitted they were not interested in unification (lowest=22.9%, highest=35.6%). On the other hand, indifference remained in the low 10% range among South Koreans in their 60s and over, with the exception in 2011 (31.4%).

Table 3. Indifference in Unification by Age10 (%)

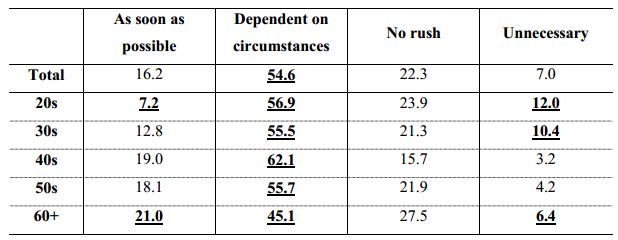

Preferred Pace of Reunification

We also looked at respondents preferred pace of reunification. Overall, a majority selected that the pace of unification should depend on the circumstances (54.6%). 22.3% answered there was no need to rush unification, and another 16.2% answered that it should happen as soon as possible. Among all age groups, the highest preference was “depends on circumstances.”

Analysis by age groups reveals that those in their 20s and 60+ had very different opinions on the urgency of unification. While 12% of South Koreans in their 20s opined that unification is unnecessary, only around half (6.4%) shared the same sentiment among the elderly. As a matter of fact, a little over one-fifth (21%) of the respondents in their 60+ said that the two Koreas should unify as soon as possible, while only 7.2% of the 20s age group answered so (40s=19%, 50s=18.1%). It is evident that the elderly have a greater sense of urgency and duty in terms of unification than respondents in their 20s.

Table 4. Preferred Pace of Unification by Age11 (%)

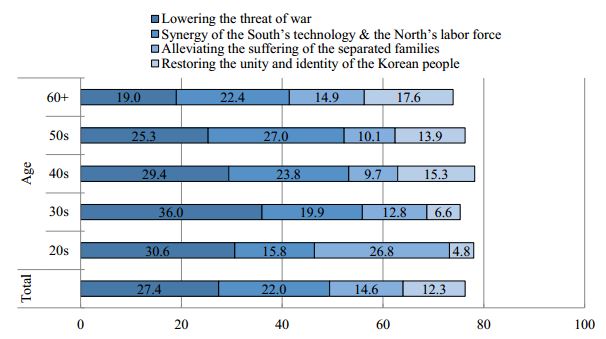

Expected Benefits of Unification

According to the 2017 survey, when asked what would be the greatest benefit of unification, most respondents answered a lower risk of war (27.4%). Another 22% selected accelerated growth created through the combination of South Korea’s advanced technology and North Korea’s labor force. 14.6% chose alleviating the suffering of separated families, while another 12.3% replied restoring the unity and identity of the Korean people.

Age cohort breakdown shows that the elderly and the younger generation have completely different views on what the greatest benefit of unification would be. Compared to other age groups, many South Koreans in their 60s and over demonstrated high expectations for accelerated economic growth and restoration of national identity, while the South Korean youth had high hopes that threat of war on the Korean Peninsula would significantly decrease.

Particularly, the ratio of those expecting the restoration of national identity was highest among the elderly at 17.6%, trailed by those in their 40s (15.3%) and 50s (13.9%). Only 4.8% in their 20s and 6.6% in their 30s chose the restoration of national homogeneity as the greatest benefit of unification.

The ratio of those expecting the elimination of the threat of war as the benefit of unification was especially high among the younger generation. Over 30% of those in their 30s (36%) and 20s (30.6%) believed that the decreased risk of war was the biggest benefit of unification. Only 19% of those in their 60s and over agreed.

The data suggests that restoring national identity through unification is not important to the younger generation. Rather, it would be accurate to say that the younger generation views North Korea as a nation threatening South Korea’s security rather than as a people sharing the same ethnic background.

Figure 3. Expected Benefits of Unification by Age12 (%)

Conclusion

The unified team controversy during the Pyeongchang Winter Olympics has raised interest in understanding South Korean youth’s perception of North Korea and unification. The Asan Institute has continuously reported on numerous occasions that South Koreans in their 20s are emerging as new security conservatives. As shown above, the younger and elderly South Koreans both shared a common sense that North Korea is a serious national security threat and opposed providing economic aid to North Korea.

However, their conservatism in security did not lead to similar views of North Korea or unification. Unlike the 60s and over, who still share a sense of national identity with the North Koreans, many of those in their 20s merely perceived North Korea as an “enemy” or a “stranger.” In addition, there were many in their 20s that were indifferent to unification and did not view it as an urgent matter. Rather, many young South Koreans take the North Korean threat so seriously that they believed the greatest benefit of unification would be the lower risk of war on the Korean Peninsula.

The survey results suggest that a unification policy emphasizing “oneness” and homogeneity would not be well received by the younger generation. Rather, the government should focus on explaining the necessity of unification in realistic terms, not with nationalistic sentiment. In other words, it would be more effective to emphasize the benefits of unification in terms of reducing national security risks rather than relying on nationalism that emphasizes the restoration of a “Korean” identity.

Sixty-eight years of division has created an identity gap among the two Koreas. It is natural that the South Korean youth cannot connect with North Korea—a country with a completely different political system, social values, and culture. In order to fill this gap, the South Korean government should start social and cultural exchanges to remedy estranged sentiment toward North Korea. Considering that social and cultural integration can be time consuming, inter-Korean exchanges should not end as mere political stunts but become a consistent policy maintained from a long-term perspective. The task of the government is to convince the younger generation that unification would be beneficial for both Koreas with realistic benefits and logic rather than emphasizing nationalism.

Survey Methodology

Asan Annual Survey

2010

Sample size: 2,000 respondents over the age of 19

Margin of error: ±2.2% at the 95% confidence level

Survey method: Personal Interview Survey (Face-to-face Method)

Period: August 16 – September 17, 2010

Organization: Media Research

2011

Sample size: 2,000 respondents over the age of 19

Margin of error: ±2.2% at the 95% confidence level

Survey method: Mixed-Mode Online Survey employing RDD for mobile and landline telephones

Period: August 26 – October 4, 2011

Organization: EmBrain

2012

Sample size: 1,500 respondents over the age of 19

Margin of error: ±2.5% at the 95% confidence level

Survey method: RDD for mobile and landline telephones and online survey

Period: September 24 – November 1, 2014

Organization: Media Research

2013

Sample size: 1,500 respondents over the age of 19

Margin of error: ±2.5% at the 95% confidence level

Survey method: RDD for mobile and landline telephones and online survey

Period: September 4 – 27, 2013

Organization: Media Research

2014

Sample size: 1,500 respondents over the age of 19

Margin of error: ±2.5% at the 95% confidence level

Survey method: RDD for mobile and landline telephones and online survey

Period: September 1 – 17, 2014

Organization: Media Research

2015

Sample size: 1,500 respondents over the age of 19

Margin of error: ±2.5% at the 95% confidence level

Survey method: RDD for mobile and landline telephones and online survey

Period: September 2 – 30, 2015

Organization: Media Research

2016

Sample size: 1,500 respondents over the age of 19

Margin of error: ±2.5% at the 95% confidence level

Survey method: RDD for mobile and landline telephones and online survey

Period: September 9 – October 14, 2016

Organization: Media Research

2017

Sample size: 1,200 respondents over the age of 19

Margin of error: ±2.8% at the 95% confidence level

Survey method: RDD for mobile and landline telephones and online survey

Period: October 19 – November 14, 2017

Organization: Kantar Public

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 1. Many criticized the unfairness to homegrown players, who would inevitably lose roster spots and playing time to accommodate the North Korean players.

- 2. Kim H. 2018. “Among 20·30 age groups, over 80 percent are against the United team in Winter Olympics,”Huffington Post Korea. January 18, 2018. http://www.huffingtonpost.kr/2018/01/18/story_n_19028432.html(accessed on February 1, 2018).

- 3. 2011~17 Asan Annual Surveys. See the appendix for more information about survey methods.

- 4. What would represent such a change is not made clear in the response options, but it would generally require a commitment to cease provocations and adherence to international norms.

- 5. The successful intercontinental ballistic missile tests by North Korea and the growing possibility of a preemptive strike on the Korean Peninsula most likely influenced the total percentage in 2017 (78%).

- 6. The age groups in Table 2 are not the same cohorts (based on year of birth) because the respondents aged between 24 and 29 in 2011 had already entered into their 30s in 2017. However, it is important to note that throughout the survey period, the 20s maintained the negative attitude toward the North Korean economic aid.

- 7. 2011~17 Asan Annual Surveys. See the appendix for more information about survey methods. In Figure 1, we asked the respondents how they view North Korea. The answers were recoded into two categories such as friendly (either ‘one of us’ or ‘neighbor’) and hostile (either ‘stranger’ or ‘enemy’).

- 8. 30s=29.9%, 40s=24.6%, 50s=30.4%, 60+=28.5%

- 9. 2017 Asan Annual Survey.

- 10. Regarding the indifference in unification shown in Table 3, it requires us to be cautious when analyzing the data since it is desirable for the respondents to show a certain level of interest in unification.

- 11. 2017 Asan Annual Survey.

- 12. In Figure 3, we did not show the responses under 10 percent [“lifting the nation’s standing and diplomatic stature in the world” (6.9%), “expanding the nation’s geographic territory” (6.8%)].

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter