Introduction1

Making sense of the presidential election in South Korea is a challenge given the last-minute breaks in polling and political maneuvering. Unpredictability of the geopolitical landscape adds greater uncertainty to the process. This year’s election is especially unique given the impeachment and removal of President Park Geun-hye. Unlike the past elections, national security has also been elevated as an important issue this year given the rising tension on the Korean Peninsula. This brief seeks to provide a primer on this year’s South Korean presidential election by outlining the positions of five leading candidates and assessing the policy implications for the next five years. We also consider the likely outcome on May 9 using the latest public opinion data, which shows the non-conservative candidates maintaining a consistent lead in the polls. Finally, we point out that whoever is elected on May 9 will face significant internal and external constraints in promoting policy change away from the status quo.

The Setup

The South Korean presidential election is determined by a single round, direct, first-past-the-post rule. Each president serves a single five-year term. According to Article 68 Section 1 of the revised South Korean Constitution (1987), all presidential elections should be scheduled 70 to 40 days prior to the end of the sitting president’s term. Under normal circumstances, the sitting president’s term would have ended on February 24; hence, all elections from 1987 until this year have been held during December 16~19. This year’s election is different given President Park’s impeachment. Under the current scenario, Article 68 Section 2 of the South Korean Constitution stipulates that the election should be scheduled 60 days after the vacancy. Since President Park was removed from office on March 10, May 9 falls within the 60-day requirement.

According to the South Korean National Election Commission, the total number of eligible voters in this year’s election is approximately 42.4 million. This is approximately 82% of the total population (51.71 million) and nearly 2 million more than the number of eligible voters in 2012. The age breakdown shows that voters in their thirties, forties, and fifties account for approximately 25 million voters (60%). In terms of region, voters in Gyeong-gi province and Seoul account for nearly 44%. If we include Busan, the major metropolitan areas account for about 51% of the total eligible voting population.

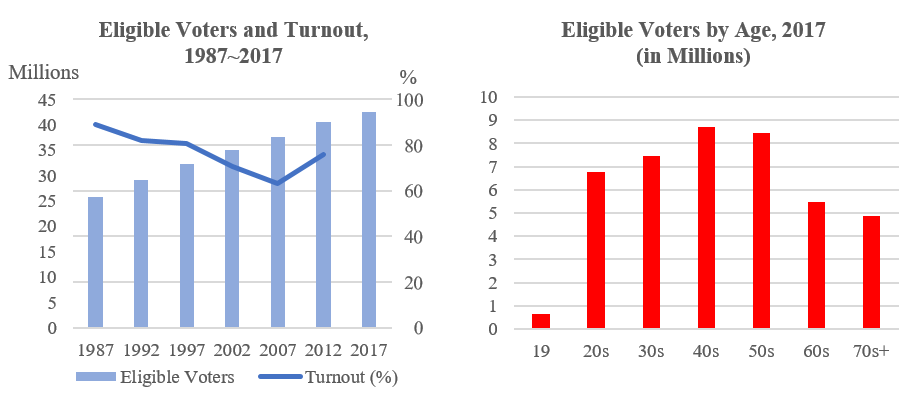

Figure 1: Eligible Voters and Turnout in South Korea, 1987-17

It is difficult to predict the actual turnout but overseas voting is at a record high with 221,981 (75.3%) voters having participated during April 25~30. Overseas voting, however, is not an accurate bellwether for the overall turnout: Overseas turnout for the 19th legislative election was higher than that of the 20th while the overall turnout was higher for the 20th with 58% than the 19th with 54.2%. Turnout during presidential elections tend to be higher than legislative elections but the overall trend has been negative since 1987 (Figure 1).

Candidates

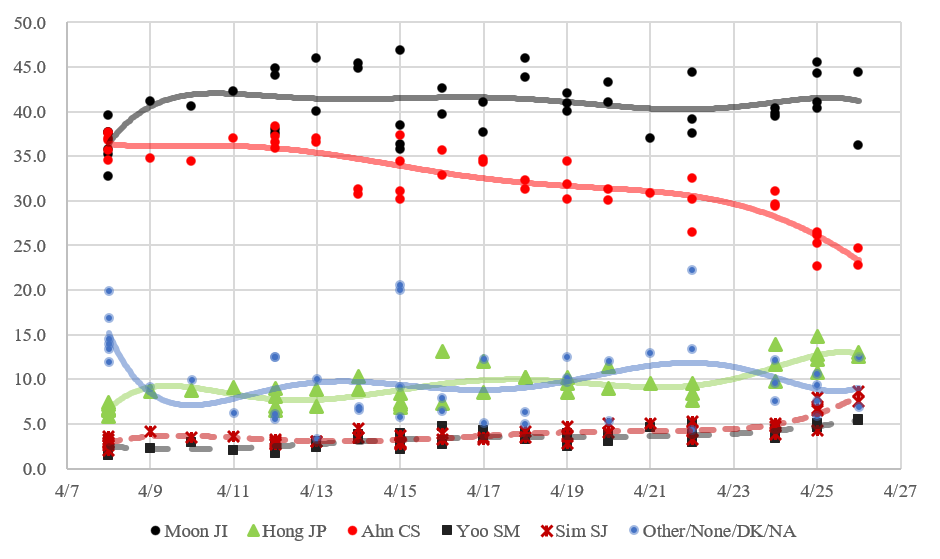

The overseas ballot lists a total of 15 candidates with one candidate having renounced his candidacy. Overall, there are 13 different parties represented in this year’s ballot (one non-affiliated). Of the 14 remaining candidates, only five participated in televised debates with each commanding sizable following in the polls. Moon Jae-in of the Together Democratic Party (TDP) holds a commanding lead since the primaries in early April (Figure 2). Ahn Cheol-soo of the People’s Party (PP) is next in the polls, followed by the leading conservative candidate, Hong Jun-pyo of the Liberty Korea Party (LKP), which is an offshoot of President Park’s New Frontier or Saenuri Party (NFP). Two other candidates have a smaller following but play no less important role in setting the agenda for this year’s election. Yoo Seong-min is a reform conservative candidate from the Bareun or Righteous Party and Sim Sang-jung is a progressive leftist candidate from the Justice Party (JP).

While it is difficult to predict the exact outcome of this year’s election, the conservatives have an uphill battle. According to the latest polls, the two leading conservative candidates (i.e. Hong and Yoo) have a combined average support of about 17~18% (See Appendix 1 and Figure 2). With neither candidate signaling a willingness to drop out of the race, the conservative votes are likely to be split among these two candidates.

Figure 2: Support for South Korean Presidential Candidates, April 8~26, 2017 (in %)2

On the other side of the spectrum, the latest combined average support for the three non-conservative candidates (i.e. Moon, Ahn, and Sim) are above 70%. Of this group, Moon has consistently maintained a clear lead. According to the latest polling at the end of April, the overall gap in support for Moon and Ahn is about 18% (See Appendix 1 and Figure 2). Perhaps even more disconcerting for Ahn is the fact that this gap has been widening since mid-April. While there appears to be approximately 10~13% of the population still undecided, that number appears to be on a downward trend as of late April. The result has been a decline in support for Ahn and a sharp rise in support for Hong, Yoo, and Sim.

The cyclical nature of Korean politics is another important consideration. Korean presidential politics tends to fluctuate between ten years of conservative rule followed by ten years of progressive rule. If this type of cyclical swings in Korean presidential election holds true this year, the leading progressive candidate will have the upper hand.

Policy Positions

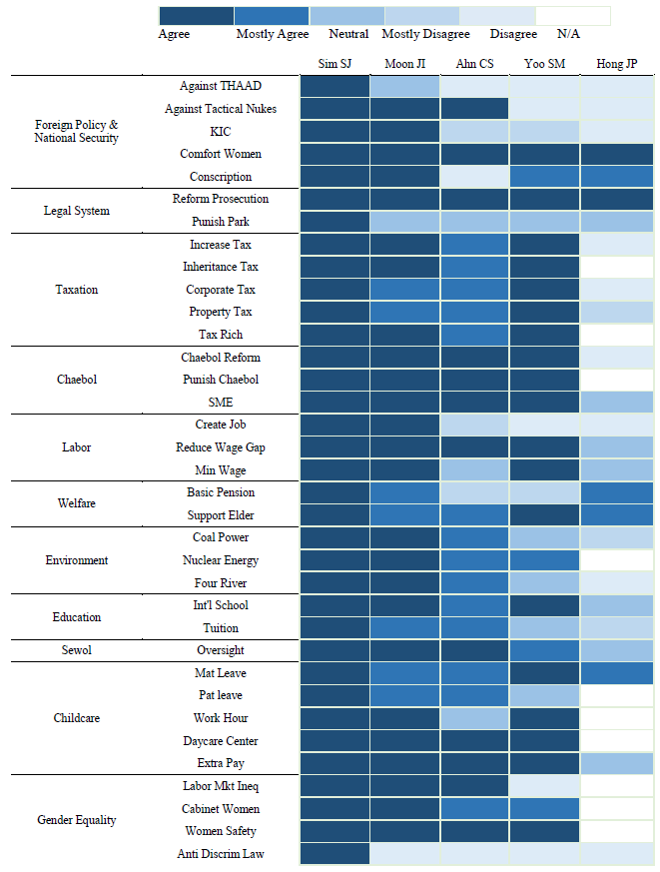

We make use of various media sources and public announcements from each campaign to assess the relative positioning of each candidate on various issues related to this year’s election (Appendix 2). As expected, our analysis shows that the two most progressive candidates (i.e. Moon Jae-in and Sim Sang-jung) share similar positions on most policy matters. There are some differences on issues related to taxation, pension, elderly support, childcare, and education but these disagreements are relatively minor. They both favor more engagement with North Korea and better relations with China. They also propose generous social spending policy for women, childcare, and working class. Finally, they share very similar views on the environment.

We also found some interesting results in our analysis which shows one of the conservative candidates, Yoo Seong-min, holding positions that are similar to the far left candidate on issues like taxation. In fact, when we compare the overall clustering of these policy positions, Yoo appears closer to the two progressive candidates than Ahn Cheol-soo. Overall, however, the difference between Yoo and Ahn is very small compared to other candidates. Hong Jun-pyo is a clear outlier in almost all categories except for certain issues like maternity leave, pension, elderly support, comfort women, and justice system reform. Let us look more closely into each candidate’s policy proposals below.

Figure 3: Heat Map of Policy Position, by Candidate3

Moon Jae-in

Foreign Policy and National Security

Moon Jae-in’s stance on many foreign policy and national security issues is not the most progressive among the five leading candidates particularly given Sim Sang-jung’s position, but his policies have garnered much more attention because many project his victory in the upcoming election. More importantly, his presidency implies a fundamental shift away from the conservative thinking that dominated South Korea’s foreign policy during the Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye administrations.

In his campaign, Moon favored developing an indigenous defense capability against the North, including the early deployment of Korea Air and Missile Defense (KAMD) and Kill Chain, a preemptive strike system. With respect to diplomacy, Moon favored multilateral efforts such as the Six-Party Talks and stated that a peace treaty is possible should the North decide to denuclearize. In addition, he proposed increased cultural, social, media, and sports exchanges between the two Koreas, the establishment of a new “economic belt” spanning the East Sea, the West Sea, and central Korea, an “economic unification” followed by national unification, re-opening of the Kaesong Industrial Complex (KIC), and signing of the South-North Basic Agreement to bring in a fundamentally new inter-Korean relationship.

Regarding the deployment of THAAD, Moon remains singularly uncommitted to a specific position. Since the beginning of the presidential campaign, Moon maintained his position that the decision on THAAD must be postponed until the next administration can negotiate with the United States and China. Other candidates labeled his policy on THAAD, or the lack thereof, as “strategic ambiguity.” He did include in his original campaign platform that he will seek the National Assembly’s approval on the budget for THAAD, although he later revised his platform and reverted back to his original policy of strategic ambiguity.

In terms of Korea’s relationship with the United States, Moon expressed his desire to maintain the strategic ROK-US relationship based on military alliance and Korea-US Free Trade Agreement (KORUS FTA), although it is unclear as to how he plans to mend their fundamental differences on issues such as dealing with the growing North Korea threat and the rise of China. Alliance management will also be important as uncertainty looms over how his relationship with U.S. President Donald Trump will develop. President Trump’s statement that Korea should pay one billion dollars for the deployment of THAAD as well as his decision to review the current KORUS FTA already stirred controversy in Korea and will test the incoming administration.

There is a widespread agreement among the major candidates on how Korea should deal with Japan. Included in this agreement is the call for the annulment of the December 2015 comfort women agreement. Moon promised that he will rectify the mistake committed by the previous administration by making the Japanese government offer an official apology. At the same time, Moon stated that the Korea-Japan relationship must develop into a mature and cooperative partnership. He agreed to include Japan in managing North Korea’s threat and declared that he will pursue a Korea-Japan Free Trade Agreement (FTA) aimed at creating more jobs and cooperating strategically in areas related to the 4th industrial revolution and new growth industries.

Economy

As part of his plan to increase jobs, Moon promised to create 810,000 jobs in areas of public and social services, including 174,000 jobs in areas of public safety and welfare, 640,000 jobs in areas of social services, and 300,000 jobs by reducing working hours (to 52 hours/week; 1,800 hours/year) and converting temporary employment into permanent employment. He also promised to create more jobs through the government’s active support of the 4th industrial revolution, creating an “innovative economic ecosystem” that will foster a better business environment for venture capital startups and, in the larger picture, resolve Korea’s negative export and low economic growth. In addition, he pledged to increase minimum wage to KRW 10,000 (approximately USD $8.80) by 2020 and increase government support of youth employment.

In terms of dealing with Korean conglomerates, or chaebols, Moon promised to eradicate special privileges that chaebols receive in order to foster a fair and just society. His plan includes reform of the current chaebol-oriented capitalistic system into an inclusive, corruption-free capitalistic system. According to Moon, illegal corporate successions, emperor-style management, and unfair special privileges among the chaebols should be strictly prohibited and monitored by a special “investigation department.”

Other

Moon pledged to improve working conditions for women including banning discriminatory employment practices, increasing the number of women in managerial positions in public and private settings, guaranteeing maternity leaves and pay, and strengthening the authority of government branches that deal with women’s rights. He also promised to increase basic pension payment for the elderly from KRW 100,000~200,000 to KRW 300,000 (approximately USD $264.00). He also supports doubling the number of job opportunities and salaries for the elderly. In terms of education, Moon’s policies include reducing the cost of education (until college), reforming the education system, expanding and guaranteeing maternity and paternity leaves, and introducing flexible working hours for parents with children between age 8 and 2nd grade in elementary school, among others.

Moon stated that a tax hike is inevitable to revive the economy, create more jobs, and reduce economic polarization, although he promised that the working and middle classes will not bear the burden. As part of that tax hike, Moon favored increasing taxes among high-income earners, increasing inheritance tax, gift tax, property holding tax, and corporate tax. He also mentioned that he will re-adjust tax reduction privileges among the chaebols in order to increase effective tax rate. Although Moon’s tax policy is aimed at increasing taxes among the wealthy and the chaebols, he failed to provide much detail in his campaign platform.

Sim Sang-jung

Foreign Policy and National Security

Among the five leading candidates, Sim Sang-jung is the most progressive on foreign policy and national security issues. In dealing with North Korea, she argued for the withdrawal of THAAD deployment (the only candidate to do so), dialogue with North Korea to freeze its nuclear and missile programs, resumption of the Six-Party Talks to discuss North Korea’s denuclearization, initiation of the Four-Party Talks to work towards a peace treaty between the two Koreas, reopening of the Kaesong Industrial Complex (KIC) and Mount Kumgang tours, lifting of the May 24 measures that prevent inter-Korean cooperative exchanges, and a summit meeting between the two Korean leaders. She also expressed her willingness to conclude a “South-North Economic and Social Cooperation Reinforcement Agreement” to systematize inter-Korean cooperation as well as to induce the North to participate in social overhead capital (SOC) and special economic zone projects to improve its economy.

In terms of South Korea’s alliance with the United States, she favors an early transfer of Wartime Operational Control (OPCON) to the South Korean forces, development of Korea’s indigenous national defense capabilities, and a complete revision of the “unfair” ROK-US Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA). In addition, in the case that the KORUS FTA is re-negotiated, she stated that she will negotiate for a more “legally equal” agreement that, for example, excludes the Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) provision that does not recognize South Korea’s domestic jurisdiction.

Regarding the December comfort women agreement between South Korea and Japan, she agrees with the other major candidates that the agreement must be nullified and re-negotiated. She stated that she will pursue a future-oriented Korea-Japan relationship but only if Japan expresses sincere regret on historical issues.

Economy

Sim is a staunch proponent of chaebol reform. Among many, she proposed the return of proceeds of crime, dissolution of the Federation of Korean Industries (FKI), and harsher punishment for chaebols engaging in corruption or otherwise illegal behaviors. She also pledged to transition from a chaebol-oriented vertical economic system to a small-to-medium business-oriented horizontal economic system. In terms of reviving the economy, she pledged government support of future industries such as electric cars and Energy Storage Systems (ESS), renewable energy infrastructures, and revival of the manufacturing industry. Further, she proposed a Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) between the two Koreas to bring in a “new era of peace and economy.”

Her labor plan includes converting temporary workers into permanent workers and, thereby, reducing discrimination and income inequality and increasing job stability. She also proposed to reduce overtime work and working hours (to 35 hours a week). She argued that the reduction in working hour will produce 50,000 more jobs. She promised to increase the percentage of mandatory youth employment (3% to 5%) and create 240,000 good quality jobs for the youth.

Other

Sim is the leading candidate in terms of her commitment to improving Korea’s social programs. Among her many proposals, she proposed to increase maternity vacation (from 90 days to 120 days) and paternity vacation (from 5 days to 30 days), lengthen paid maternity leave (from 12 months to 16 months), increase maternity pay (from 40% to 60% of wage), reduce working hours for parents during child infancy, and adopt flexible working hours for parents. She also pledged to provide basic pension (KRW 300,000 (approximately USD $264) a month) to the elderly while eliminating discrimination from employment practices and increasing government support for single parents, the disabled, immigrants, LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender), farmers, and female North Korean defectors to create a just and equal society.

Sim’s tax plan has much in common with Yoo Seong-min’s. She is a proponent of increased tax in general as well as increased inheritance tax, gift tax, corporate tax, property holding tax, and income tax for the wealthy. With increased taxes, Sim proposed to bring “justice” to the tax system and, in the process, expand welfare spending (by KRW 21.8 trillion (approximately USD $19 billion) every year).

Ahn Cheol-soo

Foreign Policy and National Security

Ahn seeks a balanced foreign policy that is based on the ROK-US alliance but places premium on South Korea’s strategic partnership with China as well as cooperation with Russia and Japan. While he recognizes issues surrounding the transfer of Wartime Operational Control and the Special Measures Agreement with the United States, he is less than clear as to exactly what he will do.

He also sees the need to build stronger national defense through the expansion of South Korean naval and air military assets. He called for increasing defense spending on an annual basis to reach 3% GDP mark by the end of his term. He also believes that continual research and development is necessary for strengthening South Korea’s capabilities to address the North Korean threat. He called for the establishment of a Strategic Command within the Joint Chiefs of Staff and a Response Center for North Korea within the National Security Council. He also favored passing new legislation to eliminate kickbacks on government defense contracts.

Ahn favors increasing pressure on North Korea through more international sanctions. But he also thinks that it is important to promote dialogue within the Six-Party and Four-Party formats. He also holds a rather broad set of objectives when it comes to the North Korean nuclear issue, ranging from a freeze on development to end of tests and even disposal of nuclear and missile capabilities. Finally, he sees 1) denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula, 2) reform/opening of North Korea, and 3) dialogue as critical steps to achieving peace and eventual reunification.

Economy

On the issue of the economy, Ahn favors chaebol reform by limiting nepotism and eliminating unfair accounting practices. He supports expanding punitive damages and consumer class action lawsuits. He also called for increased transparency and independence of the Korean Fair Trade Commission (FTC) and stated a willingness to promote market structure reform. He also stated a preference for lowering credit card fees and promoting Cash IC Card usage. According to Ahn, almost all of these changes would not require any budget line increases but he promised passage of necessary legal measures by 2018.

To promote what Ahn refers to as the national strategy for research and development (R&D) and “the 4th Industrial Revolution,” he promised to invest KRW 19 trillion (approximately USD $16.8 billion) to train and cultivate 100,000 new business leaders. He favors the idea of customized financial policy for startups and special incubation districts for startups. To head this effort, he called for more public-private partnerships (PPP) and the establishment of a Startup Small Medium Enterprise (SME) Division in his administration.

To address high youth unemployment, Ahn laid out a plan to allocate KRW 17 trillion (approximately USD $14 billion) to be used to subsidize payroll in SMEs (KRW 12 million (approximately USD $10,000.00) per employee over a two year period) and training (KRW 1.8 million per person over six months). He also called for establishing the National Wage and Job Innovation Committee to promote a system of fair and efficient employment. Some of the more radical proposals include limiting the total number of annual work hours to 1800 and guaranteeing the establishment of 1:11 rule whereby one day of work guarantees an individual 11 consecutive hours of rest.

Other

Ahn stated a willingness to upgrade existing social programs by increasing education/housing benefits while raising pension credit for veterans and families with +2 children. He pledged to raise the survivor’s pension benefit and introduce measures for full-time housewives to declare deductibles on pension contributions. He also promised to expand maternity and paternity leaves while increasing public support for pregnancy and birth.

On education, he stated that he will expand funding for public kindergarten and nurseries while improving working conditions for childcare workers. He also proposed to replace the Ministry of Education with the National Educational Committee (NEC), which will consist of politicians, teachers, and parents. The NEC will formulate a ten-year plan on the national educational policy. He also called for revising the primary and secondary education system from a 6:3:3:4 (6 years of primary, 3 years of junior high, 3 years of high school, and 4 years of college) to 5:5:2:4 whereby five years of primary and junior high school education will be followed by 2 years of exploratory vocational education before college entry.

With respect to aging and healthcare, Ahn promised to establish a Korean-style old age income guarantee system by expanding long-term care and jobs for the elderly, and reinforcing basic pension. He also proposed to eliminate standards for disability and dependent persons while promoting the enactment of the Rights for Disabilities Act. He favors lowering health insurance premium for the working class while expanding public health care service and facilities.

Overall, Ahn’s policy proposals provide some clear direction in areas like education and jobs but he is mostly vague or broad on other matters. In particular, critics argue that nearly all of Ahn’s proposals will almost certainly require additional spending; however, Ahn argues that the existing budget will only need to be tweaked and revised in order to address what he thinks are simple changes in policy priorities. This could be one of the reasons why he remains largely silent on the issue of taxation. While it is yet unclear how he plans to impose his proposed changes with the People’s Party having only secured 40 seats in the National Assembly, Ahn is a formidable contender in this year’s election trailing closely behind Moon Jae-in.

Yoo Seong-min

Foreign Policy and National Security

As a conservative, Yoo favors a hawkish national security policy with respect to North Korea and the foundation of this policy is the ROK-US alliance. For instance, Yoo proposes that the US and South Korea consider a system for “jointly managing some US nuclear assets.” While he favors denuclearization on the Korean Peninsula as a policy, he supports reintroduction of US tactical nuclear weapons in South Korea. He also proposes raising national defense spending from 2.4% of real GDP (2016) to 3.5% in order to promote defense R&D and investment in multilayered defensive capability. He called for the establishment of the Special Council for Development of Future-Oriented Defense Capacity directly under the Office of the President, which would draft and propose necessary legislative measures related to national security. He also argued for the establishment of an integrated crisis management system to better address both natural and manmade disasters. Finally, he proposes expanding the retirement age of professional soldiers by 1~3 years, depending on length of service. He also proposes providing employment insurance for workers who did not receive military pension benefits.

Economy

As a self-described “warm, clean, and just reform-minded conservative,” Yoo espouses a set of relatively progressive and well-defined economic and social agenda. The centerpiece of his economic policy is a focus on SMEs. To promote innovation, he proposes strengthening innovation safety nets by making credit recovery easier for performing managers. He also wants to enhance R&D in SMEs through the funding and support via what he calls the New Product Development Support Center. He proposes increasing deductions for venture investments and providing tax refund on those investments if the startup fails.

To promote hiring of talented workers in startups, Yoo supports expansion of tax benefits for venture firms that provide stock options for their employees. He also favors increasing government support on basic social insurance (i.e. health, pension, employment, and occupational hazard) and tax/wage incentives for SMEs. Finally, he wants to introduce retirement payment deduction and stronger wage subsidies for workers in SMEs.

Similar to Ahn, Yoo favors introducing class action lawsuits and higher punitive damages against large corporations. For instance, he proposed raising the punitive damage amount by three-folds under the Unfair Subcontract Transaction Law. He also wants to eliminate legal protection and amnesty for chaebols and prohibit the establishment of private companies by chaebol relatives and family members.

With respect to restaurant and retail businesses, Yoo called for extending the franchise contract period to 15 years and increasing the property lease period from 5 to 10 years. He also called for pegging the lease increase to inflation. To promote consumption in retail shops and restaurants, he thinks that both government and large corporate cafeterias should be required to halt operation one working day out of the week. Finally, he promised to lower the electronic transaction fees and revise the sales standards for imposing credit card fees.

Other

Yoo maintains a fairly generous and progressive social policy in comparison to Hong Jun-pyo. He favors extending parental leave from the current limit of one per child under the age of 8 to three per child under the age of 18. He proposes wage support on parental leave to be raised from KRW 1 million to KRW 2 million (approximately USD $1740.00) and allow both men and women to have access to this benefit. He also promises increasing public and private childcare facilities from the current level of 28% for 70% by 2022. Finally, he proposes childcare allowance of KRW 100,000 (approximately USD $88) per child attending primary~high school.

Similar to Ahn, Yoo promotes introducing minimum break times in between working days (i.e. minimum of 11 hours, 12 hours for parents, and 13 hours for pregnant women). He also favors setting limits on hiring temporary workers based on sector and firm size. Yoo favors the idea of minimum wage, which he proposes to increase by an annual average of 15% starting in 2018 so that it will reach KRW 10,000 by 2020. He thinks that the government should provide subsidies for employer contribution to basic social insurance premium.

Policy proposals for the elderly are also quite generous. For instance, he plans to reduce co-payments on long term care insurance while also providing maximum 12-hour per day support for patients with mild dementia or cognitive impairment and decline. Finally, he proposes to expand housing and medical support for single elderly.

With regards to national pension, he plans to guarantee minimum pension payout up to KRW 800,000 (approximately $700.00). On health, he proposes to raise the national health insurance coverage from the current level of 63.2% to 80% and increase postpartum support to KRW 3 million (approximately USD $2,600.00). Finally, he also favors expanding the coverage of National Basic Livelihood Security benefits from the current level of 3.5% to 5%.

Almost all of the spending measures mentioned above requires a corresponding increase in tax revenue, which Yoo discussed quite openly. In fact, Yoo is the most explicit on the issue of taxation by proposing an overall increase in tax burden from the current average of 19% to 22%. He also promised to introduce the “social welfare tax,” which will reset the corporate tax rate to the pre-Lee MB government level at 25% and simplify the tax code to eliminate complex and unnecessary exemption.

Hong Jun-pyo

Foreign Policy and National Security

Much of Hong Jun-pyo’s views on foreign policy and national security are similar to that of former President Park Geun-hye. The only deviation is his views on the latest comfort women agreement, where he stated his intent to support re-negotiation.

Regarding national security, Hong supports close consultation and cooperation with the United States to deploy THAAD (during the first half of 2017) as well as to re-deploy tactical nuclear weapons on the Korean Peninsula. He also supports enhancing Korea’s military capabilities to counter North Korea’s nuclear and missile threat. This includes strengthening indigenous capabilities, such as Kill Chain, Korea Air and Missile Defense (KAMD), and Korea Massive Punishment and Retaliation (KMPR). He believes in the need to upgrade surveillance and reconnaissance capabilities as well as introducing nuclear-powered submarines into Korean forces to counter North Korea’s submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) capabilities. He supports restructuring the military into four uniformed services and transitioning into a more offense-oriented military force. In terms of diplomacy, he believes that pressure and sanctions should serve as the basis for any effort to denuclearize the North. Therefore, he supports the shutdown of the Kaesong Industrial Complex (KIC) and Mount Kumgang Tours. In addition, he believes in the importance of international cooperation in dealing with North Korea.

Economy

Hong’s economic plan revolves around five goals. First, he aims to create 1,100,000 new jobs, including 500,000 jobs in small but powerful companies that are technologically competitive and innovative, 280,000 jobs in high tech and innovation sector, and 320,000 jobs in the service industry. Second, he plans to stimulate the economy through regulatory reform. His goal is to reach a growth rate in the upper 3% level. He has set the target employment rate at 70% and average national income per capita at USD 30,000. Third, he promises to foster an environment where small companies can thrive by investing KRW 10 trillion in R&D for SMEs by 2022 and reducing any unfair gaps in regulation between conglomerates and SMEs. Fourth, he pledges to reform the current labor market to reduce the gap between permanent employees and temporary workers. Lastly, he does not oppose increasing minimum wage to KRW 10,000. It is worthwhile noting that Hong is the only major candidate without a policy on chaebol reform. He has identified labor unions, not the chaebols, as the culprit behind many of Korea’s economic woes.

Other

Hong’s social policy calls for customized welfare for different age groups where he proposes to increase Family Care Allowance (in cash and voucher forms) for infants and toddlers, provide childcare allowance of KRW 150,000 per month for the bottom 50th percentile, and employment counseling, training, and job search support for the unemployed youth. He favors strengthening Earned Income Tax Credit for the low income working class and retraining for 50~60 year-old retirees as well as raising basic pension payment to KRW 300,000 for the elderly.

To address the massive private debt problem, Hong also proposes to provide public support and jobs for individuals with poor credit history in the bottom 20 percentile income category. He also offered special exemptions for non-redeemable small-to-long term overdue bonds and called for upgrading the registration criteria for debt defaults. With respect to the elderly, he proposed to broaden support for prevention and treatment of dementia as well as reduce the burden arising from higher medical expenses. On the issue of childcare support, he pledged to set financial assistance at KRW 10 million for families with 2 or more children and double the allowance on childcare support. He supports doubling the overall salary for women on childcare leave and expanding public assistance on childcare facilities. With regards to college students, he supports raising the public transportation discount level to 30% and providing housing support for youth and newlywed couples amounting to KRW 1 million.

Policy Implications

The above analysis suggests that there are strong ideological differences along party lines when it comes to national security and foreign policy. The two main conservative (i.e. Hong and Yoo) and moderate (i.e. Ahn) candidates appear to generally favor the current approach to the ROK-US alliance and North Korea. The two progressive candidates (i.e. Moon and Sim) appear to value the ROK-US alliance but favor a more conciliatory approach on North Korea. Both candidates also prefer a more balanced approach to bilateral relations with China. All five candidates appear to favor continual development of indigenous defensive capabilities but differ in the degree to which they are willing to make commitments on this issue. Conservative and moderate candidates, for instance, appear willing to allocate more resources to defense spending while progressives appear less committed. All five candidates also seem to agree that the latest comfort women agreement with Japan needs to be revisited.

In terms of social and economic policies, we find interesting similarities among all candidates except for Hong Jun-pyo. Both progressive candidates appear to favor reforms that seek to diminish the centralization of wealth and power around the chaebol while reducing inequality and unemployment. Both Moon and Yoo favor higher minimum wage and policies that seek to revitalize the SMEs. All candidates except for Hong also appear receptive to policies that expand social safety nets for women and the working class. All five candidates appear to agree on expanding social benefits for the elderly.

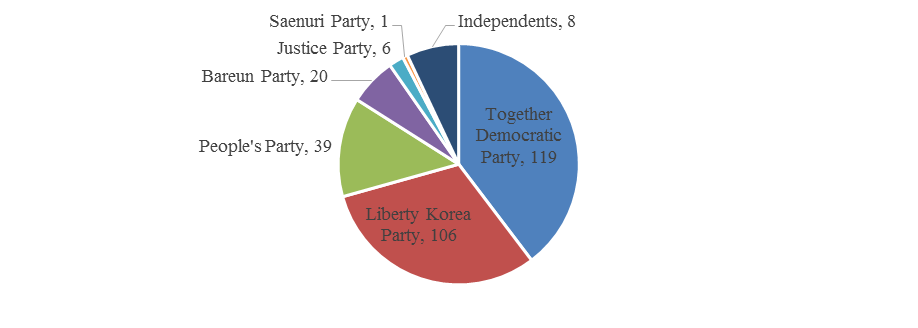

Whoever is elected into office on May 9, however, the new administration will have to come to terms with significant internal and external constraints. One major internal constraint is institutional in nature. As it stands, barring major reorganization of the National Assembly, no party will have majority legislative control (Figure 3). Even if some parties manage to form a majority coalition, it will be difficult to maintain the 60% (180 seats) threshold to pass new legislative bills through the floor. This means that introducing new reforms in the National Assembly will be just as difficult as it was under previous administration. The next general election is scheduled for April 2020, which means that the upcoming administration will have to govern a divided legislature for at least the next three years.

Figure 4: National Assembly Seats, by Party4

The second important constraint is largely geopolitical in nature. Regardless of the changes in domestic conditions, regional geopolitical landscape remains largely unchanged. Despite China’s rise, the US is still a dominant power in the region and the great power relations between Beijing and Washington remains peaceful yet competitive. Like it or not, South Korea maintains a robust security alliance with the United States and North Korea remains the most important security threat for South Korea. China’s security interests are more closely aligned with North Korea while it also sees the benefit of continued economic exchange with South Korea, Japan, and the United States. Like South Korea, Japan maintains a strong bilateral security alliance with the United States. But Japan and South Korea remain as uneasy neighbors with unresolved disagreements on historical and territorial matters. The next administration will have little room to embark on major shifts in policy given the tense environment in the region and the deeply grounded positions that the US and China have maintained with respect to the issue of North Korean nuclear problem.

Finally, the hasty manner with which this election was organized after President Park’s removal from office means that the newly elected administration will not have much transition period to settle in. The work in the Blue House begins immediately after the election without any formal personnel changes in the cabinet. What this means is that many officials from the previous administration are likely to be asked to remain in their position on an interim basis until the new appointees can take up their posts. Barring a major crisis, the new president will have to get quickly up to speed and prepare for important meetings in the coming weeks, including the G20 Summit in Hamburg during July and the UN General Assembly in September. He or she will also have to schedule important meetings with other leaders around the world. Given that the appointment for the cabinet posts require parliamentary approval, the likely timeframe for a complete transition is at least two to three months. The next administration will inevitably require time before it can begin its work on domestic reforms and foreign policy. Finally, given also the rapidly evolving security situation on the Korean Peninsula, it is not unlikely for the next South Korean president to have to make some difficult choices in the coming weeks.

Conclusion

Regardless of the choice that South Koreans make on May 9, the outcome will be one that we will have to live with for the next five years. Forecasting election outcome is a difficult business but the latest polling data suggests that one of the non-conservative candidates will likely emerge as the winner. The more important question, however, is whether the next administration in Seoul will be able to overcome the various internal and external constraints to address the challenges facing South Korea today and successfully implement the much-needed reforms.

The next administration in the Blue House will be saddled with the challenge of having to manage rising regional uncertainty as a result of the North’s fifth nuclear test and a new administration in Washington. The Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” approach to North Korea and greater demands on burden sharing by the allies create a unique challenge for the new administration. Will the next South Korean administration, provided it is a progressive one, succeed in adopting a more pro-engagement policy with the North Korean regime that is guided by the byungjin policy of prioritizing “economy and nuclear weapon?” Will the next South Korean administration gamble to test the limits of the ROK-US alliance? Or will it follow the lead of the previous administration to build on the past successes of maintaining a strong alliance relationship with the United States?

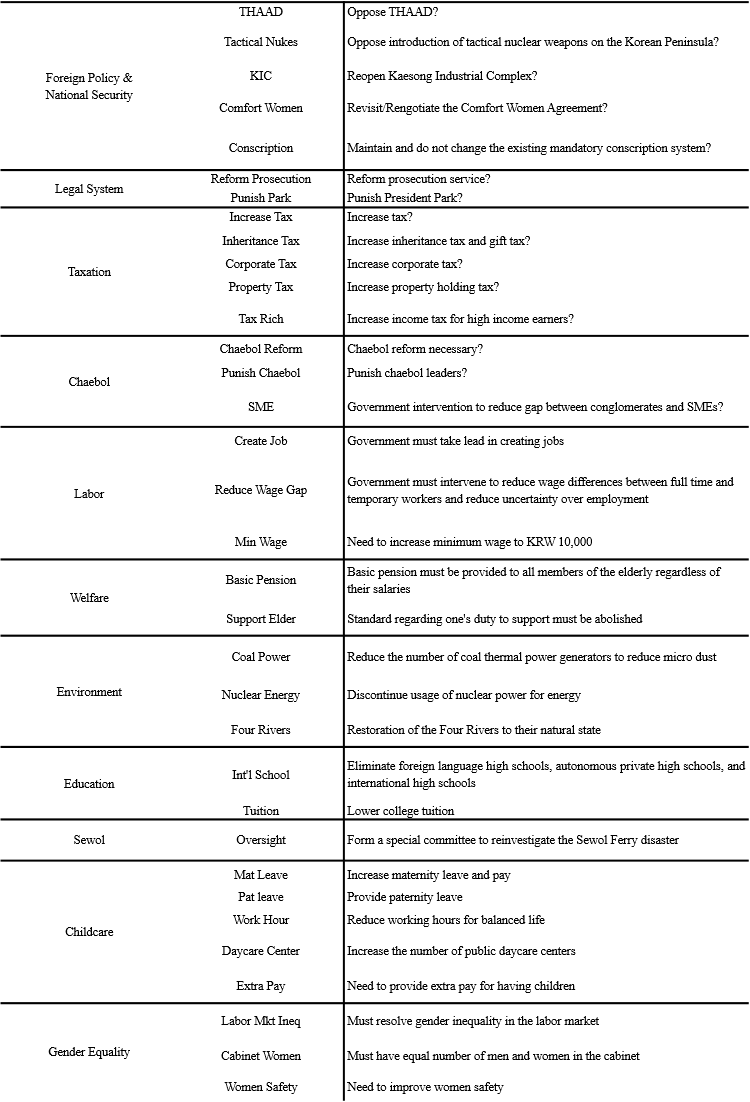

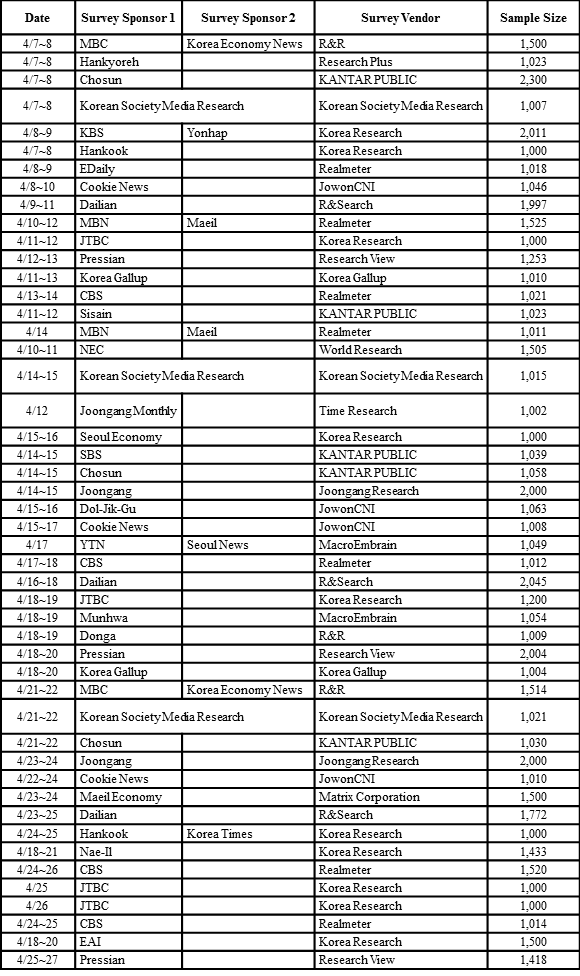

[Appendix]

Appendix 1: Survey Data Source and Dates

Appendix 2

Using various media sources, televised debates, and campaign platforms, we scored each candidate’s position on the policy questions or issues raised in this year’s election. We list below the statement/question wording for each issue. There are five possible answers the candidate can either disagree-mostly disagree-neutral-mostly agree-agree or no answer. These answers were then assigned a score between 1~5 with 1 = disagree and 5 = agree. No answer was not assigned any score. The average scoring shows Sim Sang-jung at 5, Moon Jae-in at 4.57, Yoo Seong-min at 3.91, Ahn Cheol-soo at 3.8, and Hong Jun-pyo at 2.48.

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 1.

The authors would like to thank Choi Kang, Go Myunghyun, and Eun A Jo for their comments and feedback on earlier version of this paper. Kang Chung-ku also provided assistance on the public opinion data. Standard caveats apply.

- 2.

See Appendix 1 for the list of corresponding dates and survey outlets.

- 3.

See Appendix 2 for more explanation on data.

- 4.

12 anti-Yoo members of the Bareun Party defected to the Liberty Korea Party on May 2. This increases the number of Liberty Korea Party’s seats from 93 to 106 while the Bareun Party has just enough seats (20) to maintain its status as a negotiating bloc in the National Assembly.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter