Moon-Trump summit in Washington has ended with “no deal” on how to denuclearize North Korea. Seoul’s proposals for a so-called “good-enough deal” and an “early harvest” were not accepted by the Trump administration that remains committed to a “big deal” with North Korea. The summit was followed by North Korean leader Kim Jong-un’s speech at the Supreme People’s Assembly where he urged his people to pursue a self-supporting national economy. During his speech, Kim Jong-un denounced the South Korean government for acting as a meddlesome mediator and called for Seoul to endorse Pyongyang’s position for the sake of Uriminzokkiri. South Korea is now at a crossroads between the United States as an ally and North Korea as sharing the same ethnicity. This Issue Brief will suggest some policy recommendations by exploring the latest ROK-U.S. summit in Washington.

The Summit Preparation: ‘Good-enough deal’ and Seoul’s optimism

The Proposal for a Good-enough deal

After the Trump-Kim summit in Hanoi that ended with no deal, the South Korean government sought a compromise between the big and small deals. Seoul suggested the compromise proposal for a “good-enough deal” in which the United States and North Korean authorities are committed to a comprehensive agreement on the complete denuclearization of North Korea with a step-by-step implementation.

However, the good-enough deal appears to be oriented more towards phased implementation and “early harvest” than the complete denuclearization of North Korea. The rationale behind this proposal is the idea that a series of consecutive early harvests of some sanctions relief in exchange for partial denuclearization of North Korea could help build trust between the United States and North Korea. Based on mutual trust, the two sides may ultimately reach the final goal of the complete denuclearization of North Korea. However, this good-enough deal or an early harvest seems to be more in line with Pyongyang’s “small deal” approach, rather than Washington’s “big deal” or “all-or-nothing” approach towards the denuclearization of North Korea. As a result, this has raised suspicions in Washington over its alliance with South Korea, giving signals to the no deal outcome of Moon-Trump summit in Washington.

South Korea’s optimism over the Moon-Trump summit

Seoul had been very much optimistic about the outcome of ROK-U.S. summit in Washington that ended with no deal. It seems that Kim Hyun-chong, the new second deputy director of the presidential office’s National Security Office, visited Washington and held talks with his U.S. counterpart to coordinate the agenda ahead of the Moon-Trump summit. “[W]e completely agree on our final destination, end state and the roadmap,” said Kim. “It was my first U.S. trip as a NSO deputy director. My dialogue with my counterpart, (Charles) Kupperman, went very well. I believe we can expect a great outcome from next week’s summit,” he continued.1 This raised expectations that President Trump would support President Moon’s proposal for the good-enough deal in the upcoming summit.

In Washington’s foreign policy circles, however, big deal approach has been widely supported with a growing pessimism over North Korea’s intention to denuclearize. Indeed, the United States earlier put the South Korean vessel Lunis on its Treasury Department’s list of vessels suspected of involvement in illicit ship-to-ship transfers of refined petroleum with North Korean ships. South Korean government should have read how things are going around Washington prior to the summit.

The unusual schedule of the summit

Schedule of the Moon-Trump summit raised questions whether the two leaders could have meaningful, in-depth discussions on the North Korean nuclear problem. Above all, two-hour schedule of the summit, including an expanded meeting and a luncheon, was not enough for the both presidents to discuss a roadmap for denuclearizing North Korea. In particular, in their twenty-minute of one-on-one meeting, first ladies were accompanied, making the schedule even tighter for the two leaders to coordinate their approaches to the North Korean problem.

Considering the purpose of President Moon’s visit to Washington, (i.e. to facilitate progress in inter-Korean and U.S.-North Korea talks), one could expect some kinds of formality, showing that President Trump supports the Moon government’s proposal for the good-enough deal. However, there was neither a joint statement nor a joint press conference after the talks.

The unusual schedule and form of the summit may reflect Washington’s unwillingness to support Seoul’s compromise proposal. The Moon government should have either secured more time during the summit or further proceeded the working-level negotiations prior to the summit, to elicit President Trump’s support (or ‘attention’ at least) to the proposal. If the good-enough deal had received the support or attention from President Trump, the Moon government would have strengthened its leverage in dealing with Pyongyang.

If the Moon government did not have enough time to persuade Washington during the working-level talks, it should have cancelled the protocol of accompanying first ladies to the one-on-one meeting and had more in-depth discussions with President Trump. What is worse for the Moon government during the summit was the part when President Trump showed his commitment to the big deal and the sanctions against North Korea.

The Moon government should have also considered suspending the summit if the two sides had not successfully coordinated, in the working level talks, their policies to denuclearize North Korea. It is fair to say that Washington knows how difficult it is for North Korea to embrace the big deal, and therefore could, in the end, positively consider Seoul’s proposal for good-enough deal. Nonetheless, it is not the right time for the United States to make a concession right after the Hanoi summit – it might be waiting for the right moment. The Moon government was too optimistic and naïve in persuading the Trump administration to accept its compromise deal.

It appears that the South Korean government, despite all the uncertainties, pushed ahead with the Washington summit because it believes in the effectiveness of the top-down approach in negotiating with the Trump administration. Seoul seems to have focused more on meeting and persuading President Trump directly, rather than convincing his foreign policy team during the working-level talks. However, President Trump has changed; he has reportedly developed a more in-depth knowledge of the complex dynamics around the North Korean nuclear problem in the course of preparing for the Hanoi summit. The Moon government, however, was still optimistic about altering Washington’s strategy towards Pyongyang through direct deal with President Trump. Consequently, the Washington summit ended with no deal.

The gap between Seoul and Washington on a roadmap for North Korea’s denuclearization

The two leaders basically agreed on the need to resume talks with Pyongyang, yet could not bridge the gap in other important issues such as conditions for resuming talks with Pyongyang, a roadmap towards denuclearizing North Korea, and resuming Mount Kumgang tour program. President Moon seems to have called for Washington to provide a partial lifting of sanctions (ex. resumption of Mount Kumgang tour program or operation of the Kaesong Industrial Complex) in exchange for the disposal of the Yongbyon nuclear facility.

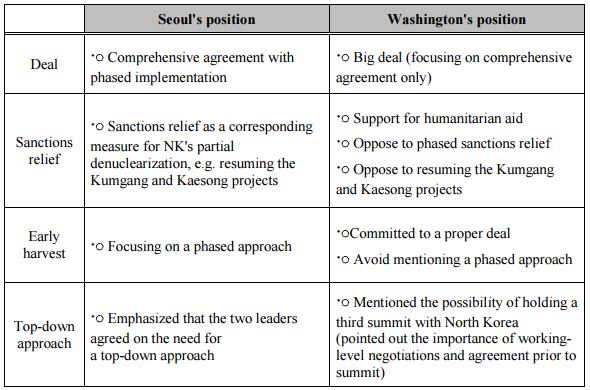

However, President Trump reportedly showed his commitment to the big deal approach towards the North Korean nuclear problem, and refused to resume Mount Kumgang tour and the Kaesong Industrial Complex at this juncture. Indeed, the different interpretation on the summit between Seoul and Washington epitomizes that the two sides have not yet reached an agreement on how to denuclearize North Korea. More specifically, while South Korea’s senior official said that the two sides “shared a view” during the summit, the White House, in its official release, said that the two leaders “discussed” their goals of the FFVD of North Korea. In short, it is safe to say that there are substantial differences in views between Seoul and Washington over how to tackle the North Korean problem.

Table 1: The gap between Seoul and Washington on a roadmap for North Korea’s denuclearization

One of the big differences between the two sides is the sanctions relief agenda. Right after the breakdown of the Hanoi summit, President Moon said he would discuss with the U.S. the possibility of resuming of Mount Kumgang tour and the Kaesong Industrial Complex. However, President Trump, during the summit with President Moon, showed his unwillingness to provide a partial lifting of sanctions in exchange for Pyongyang’s small gestures.2 Although the two leaders agreed not to impose additional sanctions against North Korea, President Trump said that the U.S. wants sanctions to “remain in place.” “There are various smaller deals that maybe could happen…But, at this moment, we’re talking about the big deal. The big deal is we have to get rid of the nuclear weapons,” he said during a question-and-answer session with the press before going into the bilateral meeting. President Trump appears relaxed and confident about the effectiveness of sanctions that, he believes, could induce significant changes in North Korea’s strategic calculations.

The current situation and near-term prospects

After talks with President Trump, President Moon said he would seek to hold another inter-Korean summit regardless of venue and form. It is less likely, however, that Pyongyang will respond positively to this proposal. As President Moon failed to convince President Trump to embrace the good-enough deal, North Korea may now change its strategy from persuading Washington through Seoul to engaging directly with the United States.

Kim Jong-un’s speech before the Supreme People’s Assembly on April 12 may illustrate North Korea’s policy towards Seoul and Washington. With regards to North Korea’s policy towards the South, Pyongyang has been consistently urging South Korea to take a proper stand through nationalistic appeal of Uriminzokkiri. During his speech, Kim Jong-un called for President Moon to stand by his side rather than acting as a meddlesome mediator.

North Korea’s policy towards Washington is twofold. On the one hand, it maintains the atmosphere of dialogue with the Trump administration. At the same time, it called for Washington to embrace a phased approach. In his April speech, Kim Jong-un said that he would wait until the end of this year for the United States to make a courageous decision, implying that he would otherwise carry out a strategic provocation such as a missile test next year. That is, North Korea is threatening President Trump who has been claiming that North Korea has not tested missiles or nuclear weapons since he initiated talks with Kim Jong-un. Pyongyang could therefore try to make use of the U.S. presidential election next year. This year, North Korea may focus on promoting a self-supporting national economy and strengthening its ties with China and Russia. It is still possible that North Korea will again fire short-range ballistic missiles which it tested on May 4 and 9. However, it is unlikely that North Korea would carry out significant military threat such as firing intercontinental-range ballistic missile (ICBM), which could cause additional sanctions by UN Security Council. In short, North Korea has very few options.

Against this backdrop, the current standoff between the United States and North Korea is likely to continue for the time being. The Trump administration may try to manage the current situation by resuming humanitarian aid to the North. However, it is unlikely that humanitarian aid could induce Pyongyang to change its position. Indeed, the Trump administration remains focused on a big deal approach towards the North. On the other hand, North Korea prefers to have NK-U.S. dialogue first. It is difficult to imagine the resumption of inter-Korean talks until Washington changes its position. There is, therefore, little prospect for holding another inter-Korean summit in the foreseeable future.

In short, North Korea, for the time being, seems to focus on pursuing economic development and strengthening social control, whilst increasing its leverage against the United States by strengthening ties with China and Russia. It could continue its military activities, including nuclear activities, as a ways to put pressure on South Korea and the United States. However, it is unlikely that the North would carry out significant provocations, such as satellite launches and ICBM launches, which could result in additional sanctions.

Policy recommendations

Cautious approach to North Korea

The Moon Jae-in government is likely to try to have under-the-table contacts to send a special envoy to Pyongyang or to hold another summit with Kim Jong-un. It is not a bad approach in itself. However, the government must take a cautious approach. In fact, the recent visit to Washington was not urgent given the uncertainty about how the Trump administration will respond to the President Moon’s proposal. Seoul should have precisely read the atmosphere in Washington. Indeed, the Washington no-deal summit even forced North Korea to turn its back to the South.

Another inter-Korean summit may serve Seoul’s interests only when it is pursued by North Korea rather than the South. The good news is that both the United States and North Korea want a third bilateral summit. Indeed, it is unlikely that tensions around the Korean Peninsula will be escalated further. Hence, Seoul does not need to rush the negotiation process to hold another summit with the North. Seoul must bear in mind of the saying “more haste, less speed,” and now focus on creating favorable conditions for a successful summit in the future.

Tackling North Korea based on a strong ROK-U.S. alliance

With the lack of United States’ confidence in the Moon government, South Korea could lose its leverage against North Korea. Seoul needs to work towards strengthening its alliance with the United States to induce Pyongyang to denuclearize. Only when Seoul and Washington closely coordinate with each other, one could expect successful denuclearization talks among the two Koreas and the United States.

In order to strengthen the ROK-U.S. cooperation, the two countries should, first of all, seek a common understanding of what exactly “denuclearization” means. Unlike the United States using the term “denuclearization of North Korea,” the Moon government uses the term “denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.” The term “denuclearization of North Korea” is more accurate and can prevent abuse by North Korea. By denuclearization of North Korea, it includes the declaration and verification of relevant materials, weapons, facilities and personnel. Time schedule is also important; Seoul and Washington should work closely together and make a specific plan on what to do by when and how.

Inter-Korean relations based on mutual respect

Kim Jong-un’s devaluation of Seoul as acting as a meddlesome mediator, together with the earlier humiliating cold noodle remark by North Korea’s unification committee chief Ri Sun Kwon, may epitomize how Pyongyang sees South Korean government and its people. The problem is that the Moon government has not lodged any significant complaint against Pyongyang in response to these insulting remarks. In this way, we cannot solve the North Korean nuclear issue, or more broadly, the North Korean problem. It must be noted that the North Korean nuclear problem is fundamentally linked to inter-Korean relations. The South Korean authorities, therefore, must be committed to building Inter-Korean relations based on mutual respect in order to resolve the North Korean nuclear problem, and beyond.

The use of the term ‘good-enough deal’

The good-enough deal could be a useful policy option in denuclearizing North Korea, though it was not welcomed in Washington in the latest summit. It is advised that the Moon government continues to pursue this compromise deal, but needs to be cautious about the term. It is advised that the government uses the term “comprehensive agreement and phased implementation,” rather than the term “good-enough deal” or “early harvest” which may cause misunderstandings.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter