1. Introduction

It may seem presumptuous to begin considering medium term strategic stability in the Korean peninsula when the 2017 crisis has not yet fully deescalated. Nevertheless, there is distinct difference between the urgency of crisis management – which is an appropriate characterization of the dramatic events surrounding North Korea’s sixth nuclear weapon test and incessant missile launches – and learning to live with the altered reality that these advances in its military prowess are ushering in.

Moving beyond the 2017 crisis will require South Korea, the U.S. and China to find some common ground in order to, at the very least, contain the threat posed by North Korea. At best, North Korea would be forced to change its nuclear strategy. All three countries agree at least in principle that the Korean peninsula should be a nuclear-free zone, but they have fundamentally differed in their responses to North Korea’s recent destabilizing actions.

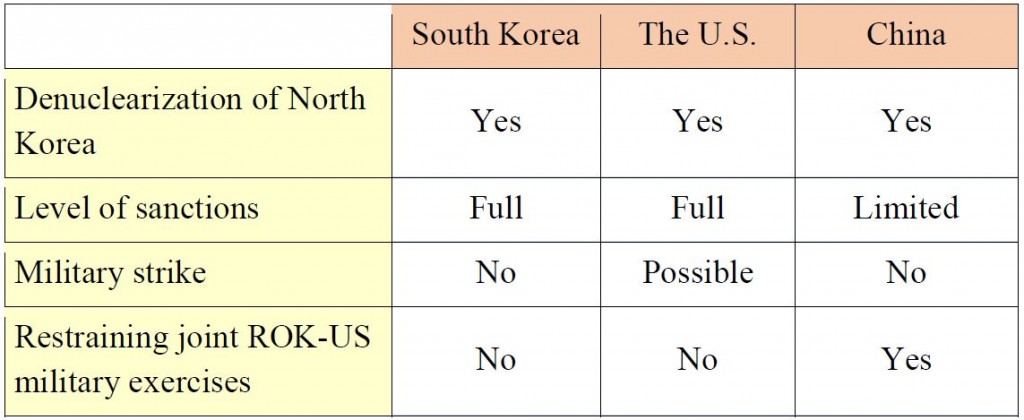

This Issue Brief considers the strategic choices facing South Korea, the U.S. and China in adapting to the medium term realities of a future post-crisis environment. Their respective positions on key issues as ‘denuclearization of North Korea’, ‘level of sanctions’ and ‘military strike’ and ‘restraining joint ROK-US military exercises’ are illustrated in Table 1. This comparison summarizes the inherent difficulties in finding common ground for action between these countries.

Table 1. South Korea, U.S. and China: positions on key issues1

North Korea’s nuclear program began in the early 1990s and has continued more or less unabated for over two decades. Ever since Kim Jong-Un succeeded his father, Kim Jong-Il, in late 2011, the number of missile launches and nuclear tests has soared. According to CSIS,2 there have been so far 94 missile launches and 4 nuclear tests over a 6-year period (2012-17) of Kim Jong-Un’s reign compared to 44 missile launches and 2 nuclear tests during his father’s 17-year reign (1944-2011). This is a clear indication that Kim Jong-Un is pouring resources into nuclear and missile programs, a family legacy he must complete.

In 2012 North Korea revised its constitution to declare itself ‘a nuclear state,’ which was perhaps intended to force any negotiations with U.S. to be on more equal terms. In the following year, Kim Jong-Un has adopted and maintained the dual policy of “Byungjin”3 which calls for economic and nuclear development in parallel. It is also worth remembering that North Korea’s main policy objective has all along been the reunification of Korea on its own term after its failed attempt in 1950. All these facts strongly support the view that North Korea is unlikely to dismantle all of its nuclear and missile programs.

Against this backdrop, this Issue Brief examines the contrasting positions of South Korea, the U.S and China in greater detail be in the sections that follow. First, a summary of how tensions escalated during 2017 is provided. Next, the positions taken by the U.S., China and South Korea during the crisis are examined in turn.

The section on the U.S. shows that no matter how tempting it has been for US President Donald Trump to allude to decisive action against North Korea, the real challenge resides in managing and not solving this precarious scenario. The section on China explores the medium term implications of its more restrained response to the crisis. The section on South Korea explores its policy options in light of seemingly insurmountable differences on crucial issues between the countries involved in the crisis and the looming reality of a nuclear armed North Korea. To conclude, observations are drawn from across these national positions to consider pragmatic steps required to restore strategic stability on the Korean peninsula.

2. How tensions escalated in 2017

Tensions were already high after the North Korean regime test-fired a number of medium-range ballistic missiles into the sea near the coast off Japan during April and May 2017. Twice in July 2017, the Hwasong-14 Inter-Continental Ballistic Missile (ICMB) was tested, demonstrating a potential capability to hit the U.S. mainland. The speed with which North Korea has developed its missile technology is of immediate concern to the U.S. and South Korea.4 The U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) concluded that North Korea would be able to produce a “reliable, nuclear-capable ICBM” sometime in 2018.5 In early September, North Korea carried out its sixth nuclear test, claimed to be a hydrogen bomb by its state media.

This crisis has played out as a series of provocative actions by North Korea and threats by President Trump. The first Hwasong-14 missile was fired on the symbolic date of 4 July, U.S. Independence Day. After the second Hwasong-14 missile was fired, Trump warned of “fire and fury” awaiting North Korea if it threatened the U.S.6 In August 2017, North Korean leader Kim Jong-Un threatened to launch ballistic missiles into the sea near the U.S. territory of Guam, which is a home to a fleet of B-1B and B-52 strategic bombers. Trump again warned North Korea to expect “big, big trouble” if it launched an attack on Guam, tweeting that “military solutions are now fully in place, locked and loaded, should North Korea act unwisely.”7 Trump delivered another warning at the UN: “If [the U.S.] is forced to defend itself or its allies, we will have no choice but to totally destroy North Korea.”8

Whereas the world has become accustomed to the hyperbolic threats of the North Korean regime, there is worrying novelty in seeing an American president employ similar language. Kim Jong-Un seemed to have backed away from his threats to launch missiles close to Guam, but tensions remained acute after North Korea fired two Hwasong-12 medium-range missiles over Japan on 19 August and 15 September 2017. In another symbolic act, the first of these missile tests took place during the annual South Korea-U.S. Ulchi-Freedom Guardian (UFG) joint military exercises in August.

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Defense Secretary James Mattis reaffirmed the U.S. position: Washington is prepared to respond militarily, if necessary, but prefers a peaceful solution to the standoff. An announcement to this end was delivered after a “2+2” meeting in Washington with Japanese counterparts.9 North Korea’s edging closer to attaining nuclear ICBM capability has set alarm bells ringing in Seoul and Washington.

Years of former President Obama’s strategic patience appeared to have given North Korea time to develop its capabilities without feeling the pain of severe economic sanctions. President Trump’s administration has taken a far tougher stance by keeping military options on the table, and following through on a threat to limit Chinese and Russian companies from seeking business with North Korea. It has also reinstated North Korea to the State Department’s list of State sponsors of terrorism. However, the key question remains as to whether this tougher stance will yield any concrete results.

Moreover, we should ask: what is the lasting significance of the 2017 crisis? Despite all that has happened, the matter of North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs has dragged on for decades. Arguably, some fundamentals of the scenario remain unchanged. U.S. strategy is still focused on deterring and containing North Korea and urging China to rein in its economically dependent neighbor. The scenario still involves managing periodic spikes in tensions rather than addressing root causes. So long as the problem is perceived as a zero-sum game by the countries most concerned with the scenario due to their immediate interests,10 then there remains little hope in reaching a permanent solution.

3. U.S dilemmas: transcending Trump’s ‘madman’ approach

The ‘madman theory’ is a term from the Cold War that explains the purposeful injection of a sense of unpredictability by one or both sides during a national security crisis, in order to enhance the credibility of their threats. It is a useful characterization of Trump’s approach to North Korea which, for all of its apparent toughness, has also forced Kim Jong-Un into further displays of his regime’s military vitality simply to retain face.

Washington and Pyongyang have been playing out a game of chicken during the 2017 crisis. The danger is considerable, given that Pyongyang has used this tactic with some success in the past, but this time with Trump taking the challenge head-on. There is a narrow margin for error between the two players. It appears that Kim Jong-Un has yielded from his threat on Guam. But the high risk game has continued with both Trump and Kim Jong-Un using the media to convince each other they cannot back down, since doing so would weaken each to his constituents.

Has Trump’s adoption of the ‘madman’ approach tipped the balance in his favor this time? There is an argument to be made that Trump’s language, of an eye for eye and tooth for tooth, is the only mode of communication North Korea understands, and therefore carries credibility and unambiguity in this context. However, this approach seemingly reflects Trump’s impulsive personality traits, and risks leading the situation into dangerous waters.

During the Cold War, the late Nobel laureate Thomas Schelling reflected on “the apparent restrictiveness of an assumption of ‘rational’ behavior” – in a crisis there might be some value in appearing to be out of control, to scare your opponent to concede.”11 The ambiguity of Trump’s threats fits this pattern. The concern, however, is that U.S. intentions are misinterpreted in Pyongyang, inadvertently motivating North Korea to act in even more damaging ways. Hence, it is in U.S. interest to project a clear and consistent message of deterrence. As Baliga observes, “in national security, predictability can definitely pay.”12

Despite Trumps’ rhetoric and threats of military action, the fundamentals of the scenario have not changed. There is no realistic chance that a preemptive US military strike would achieve anything other than widespread destruction along the Korean peninsula, since pinpointing all of North Korea’s nuclear weapons would not be possible. One should also take into consideration North Korea may be unable to determine if it was a limited strike, or the start of a full-fledged war. Limited war is not an option, and South Korea and the U.S. would have to be fully prepared to go to war before taking such action.

As Herman Kahn remarked during the Cold War, “[The U.S.] must not look too dangerous to our allies [who] must believe that being allied to us actually increase their security.”13 He advocated “safe-looking” limited war forces to handle minor and moderate provocations. While it is not immediately clear what “safe-looking” limited war forces would correspond to when countering North Korean provocations, Pyongyang should be left in no doubt that the U.S. remains committed to the security of the region – but that the U.S. commitment is credible and sustainable, rather than based on episodic flashes of anger by Trump.

U.S. policy choices still center on deterrence and containment. These Cold War-era theories withstood the test of time in preventing all-out war between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. The theories must be scrupulously re-examined and adjusted to account for modern technological and geopolitical realities, and to ensure their enduring relevance.

There is no doubt that North Korea will become more daring and will keep probing and trying to drive a wedge between the U.S. and its Asian allies. Without tempting fate, the present crisis will be weathered and the situation will be contained and managed through appropriate countermeasures. Although this remains deeply unsatisfactory for South Korea and for the U.S., it is the most pragmatic way of conceptualizing the scenario.

4. China’s dilemmas: appease the U.S.; avoid a North Korean collapse

During 2017 crisis the U.S has attempted to cajole China’s government into exerting more pressure on its neighbor, North Korea. North Korea is unmistakably dependent on its trade with China, and China purchasing North Korean iron ore, zinc, coal, seafood and other commodities. According to Chinese data released in April 2017, the volume of its trade with North Korea has in fact grown 37.4 per cent in the first quarter of 2017 compared to the same period in 2016. Ex-Chinese diplomat Yang Xiyu was quoted in The New York Times explaining that “It’s hard to ban normal trade that is not prohibited by UN resolutions.”14

Yang Xiyu led China’s delegation to the Six-Party Talks on North Korea’s nuclear arms program that were held from 2003 to 2007. As Andrew Scobell notes, this was “the most significant and sustained instance of U.S.-China cooperation on North Korea in the past two decades… although the talks did not ultimately have a happy ending.”15 What is it, then, that explains China’s reticence to increasing pressure on North Korea?

As with so many other aspects of its foreign and security policy, China’s approach to North Korea appears cautious and cognizant of Beijing’s longer-term aspirations for the region. There are no clear incentives for President Xi Jinping to assist Trump in resolving the 2017 crisis in a manner that allows the U.S. to have made a decisive intervention in Asia. At the UN Security Council, China has (in step with Russia) forced the U.S. to water down the strength of its proposed sanctions on North Korea.16 The drama of the UN Security Council chamber, and its accompanying political horse-trading over the sanctions resolution, is merely symbolic of a deeper strain within Chinese thinking.

China’s rise as a global power ought not to distract attention from the fact that its role as a regional power is where its influence is most likely to be felt most tellingly. Unfortunately for China, the North Korea issue allows the U.S. to repeatedly intervene in Asian affairs – a domain in which China expects to gain predominance in decades to come.17 After North Korea’s nuclear tests in 2006 and 2009, China’s response was, if anything, even more cautious. This led Lora Salmaan to conclude in a Carnegie-Tsinghua paper that: “China is more likely to continue to seek a balance between keeping the U.S. preoccupied and dissuading it from an extreme response that would harm Beijing’s interests.”18

China’s response to the 2017 crisis so far bears out this assessment. North Korea is an open sore for China, but one it lacks any clear incentive to heal. For Beijing, Pyongyang’s insular regime remains an unpredictable factor that threatens to bring deep instability to the region. Beijing remains Pyongyang’s key backer, but China is no writer of blank checks for North Korean adventurism, wary as it is of becoming embroiled in a conflict instigated either by the rashness of Kim Jong Un or Donald Trump, and of the chaos that would arise from a North Korean collapse.

Not even the literal reverberations of North Korea’s latest nuclear test spurred China into action. China was forced to monitor radiation levels on its own territory after the test, which was felt along China’s 880 mile border with North Korea. Diplomatic embarrassment followed for President Xi, who was hosting the BRIC’s summit at the time of the test.19

Ultimately, if China has a red line in relation to Kim’s regime, then it is far more likely to opt for quiet diplomacy to deescalate the crisis than to opt for any kind of public censure that would hand Trump a reward for his aggressive rhetoric. The very last thing China will want to do is validate U.S. sabre rattling in its own region. Moreover, China’s long term goal likely coincides exactly with that of North Korea, in that both will want U.S. forces out of the Korean peninsula. As Trump has argued for haste in exerting pressure on North Korea, time is not of the essence when playing China’s long game.

Hence, China may take the position that the 2017 crisis is a storm to be weathered, and in years or decades to come, the situation can only be addressed by replacing the current armistice between the U.S. and North Korea with a ‘peace treaty’, in which the eventual withdrawal of U.S. forces from the Korean peninsula is exchanged for the complete dismantling of North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs. All of this is hypothetical, and depends on China also being able to sell this idea to Russia. But any future developments along these lines would leave South Korea exposed and vulnerable.

5. South Korea’s options: deterrence and containment

South Korean President Moon Jae-in, a liberal, had only assumed office this May, having succeeded the scandal-ridden presidency of Park Geun-hye. He has stressed the need for South Korea to take a leading role in managing affairs on the Korean peninsula, seeking permanent peace on the peninsula via peaceful resolution to the nuclear crisis.20

At present, Seoul is pursuing a two-track policy of sanctions and dialogue aimed at forcing North Korea to negotiations. North Korea continues to threaten South Korea, the U.S. and Japan while resisting negotiations unless recognized as legitimate nuclear state. South Korea should hone its diplomatic approach to tightening of sanctions. However, it is easier said than done since China and Russia have previously tried to water down the severity of sanctions in light of their strategic interests. Nevertheless, without their cooperation it would be difficult to bring enough pressure to bear on the North Korean regime. In November 2017, Trump again called on China and Russia to fully implement UN Security Council resolutions in his speech to South Korea’s National Assembly.

South Korea must make every effort to enforce a U.S.-led push for tightened UN sanctions on North Korea. Efforts should be centered on bringing ‘unprecedented international sanctions’ to bear and ensuring existing sanctions are not flouted by any UN member state, with due consideration over how North Koreans may bypass measures put into effect. Clearly, the sanctions must be maintained and given enough time to bite, no matter how hard North Korean State Media tries to downplay their impacts. As a salutary lesson from the past, it was economic collapse, and not war, that eventually brought about the Soviet Union’s demise. Here, it is the denuclearization of North Korea which is sought and not its demise, and Trump has offered a ‘brighter path’ for North Korea in his speech to South Korea’s National Assembly.

Furthermore, on the killing of Kim Jong-Nam using a banned VX nerve agent, as well as on human rights in North Korea more broadly, South Korea could drum up more support from countries in South East Asia and beyond that have diplomatic or trade relations with North Korea.21 To overcome the inherent limits of UN sanctions,22 there should be separate efforts outside the UN to encourage like-minded countries to cut the flow of cash to Kim Jong-Un’s regime through, for example, sending back North Korean laborers and closing down of North Korean businesses (e.g., restaurants and shops).

Besides the ‘unprecedented international sanctions’ mentioned earlier, South Korea must strengthen its deterrence in face of North Korea’s rising menace. There must be a thorough review of South Korea’s current defenses. This should be based on careful study of North Korea’s evolving strategy and tactics, which will feed into the planning process to ensure that South Korea has military resources and capabilities to counter any type of attack from the entire spectrum of North Korean threats. The acquisition of weapons systems from overseas should be considered to plug holes in the defense if they cannot be locally supplied in good time. For collective defense, South Korea and Japan need to deepen cooperation beyond sharing of intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance. The two countries can go further and complement each other’s military capabilities in areas such as missile defense, submarine tracking-hunting and mine-sweeping.

In times of challenge, it is a matter of paramount importance for South Korea, the U.S. and Japan to coordinate the sending of a coherent and unequivocal response that North Korea faces serious and credible consequence for its provocations. Collectively, these countries can send a stronger message to Pyongyang to deter further provocations, something that has to be visibly reinforced by the strengthening of defensive measures.

From a South Korea’s perspective, the re-deployment of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons should remain an option. Incorporating NATO-type nuclear sharing arrangements with the U.S. should be seriously considered in order to re-establish deterrence on the Korean peninsula (see the work of Cheon23 for full details). This should reassure South Koreans’ concerns over the robustness of U.S. extended nuclear deterrence. It is premature and perhaps even naïve of South Korean government officials to discard such option so openly without careful consideration.

To strengthen its defense capability against a multitude of missile threats, a countrywide multi-tiered missile defense system needs to be deployed to protect critical infrastructure and densely populated areas like Seoul. South Korean Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-wha pledged that South Korea would not seek an additional THHAD battery, as part of her diplomatic efforts to resume normal relations between South Korea and China, after China had taken economic revenge over the deployment of a U.S. THAAD battery in Seongju this year. However, there should be clear limits on what could be negotiated away, and certainly not at the expense of endangering the lives of several million residents of Seoul.24

The South Korean government has a difficult balance to strike, at one maintaining policy coherence with its allies, while also needing to drive matters forward on its own initiative. It must allay China’s concern that its national interests are not impinged. This is sometimes a difficult task as it may cause concerns with the U.S. However, South Korea’s security concerns must take priority. It is necessary for South Korea’s government not be overly swayed by short-term interests, even if there is a need to respond to breaking events. The 2017 crisis places greater agency on South Korean actions and policy decisions, not least since it re-emphasizes the fact that U.S. and Chinese national interest calculations cannot be the only driving factors in finding a way out of the crisis.

6. Conclusions

Advances in North Korean missile and nuclear testing, and the rashness of U.S. rhetoric, has returned the international spotlight to the Korean peninsula. Managing and ultimately deescalating the crisis is the absolute priority, before the restoration of strategic stability can be considered. Thinking along these timescales, a number of observations can be made in relation to the 2017 crisis.

As shown in Table 1, China’s position makes it difficult to find a common denominator at the lower working level, a stepping stone from which to make further progress towards denuclearization on the Korean peninsula. Without a paradigm shift, even reaching a tentative agreement over the level of sanctions required will demand strenuous efforts. The road to denuclearization, if feasible, is going to be a long drawn-out process with many difficulties and an uncertain outcome. All signs indicate that facing the challenges of a nuclear armed North Korea has become a stark reality.

As a consequence, South Korea should take on greater responsibility for its own defense and security. Its military must plan ahead to ensure that it is fully prepared to deter and defeat any type of attack from the entire spectrum of North Korean threats. Maintaining deterrence on the Korean peninsula should also be considered as imperative in reassuring South Koreans who are concerned by the crisis. As pledged by South Korea, Japan and the U.S. during Trump’s Asia trip, the trilateral security cooperation between these countries must be strengthened in face of North Korea’s rising menace. Whereas South Korea and its allies must be fully prepared to back up words with actions, they must also avoid falling into the trap of overreacting when provoked. If past experience is anything to go by, North Korea has taken a confrontational stance to elicit concessions. At times, it may well be wise to resort to willful ignorance.

On the diplomatic front, it can do more to make its voice heard rather than being rendered a passive player, caught in the shadow of the Chinese and American behemoths. Despite all the difficulties and challenges, South Korea can intensify its domestic and overseas efforts towards bringing ‘unprecedented international sanctions’ to bear on North Korea’s regime. The end goal is not North Korea’s demise, but a mutually satisfactory resolution of the nuclear crisis.

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 1. Japan’s position is the same as U.S. whereas Russia’s position is the same as China.

- 2. North Korean Missile Launches & Nuclear Tests: 1984-Present (updated 20th September 2017), CSIS Missile Defense Project.

- 3. “Byungjin” (Parallel Development), GlobalSecurity.org.

- 4. Michael Elleman, “The secret to North Korea’s ICBM success, “International Institute for Strategic Studies, Policy Brief, 14 August 2017.

- 5. The Washington Post, “North Korea could cross ICBM threshold next year, U.S. official warn in new assessment,” 25 July 2017.

- 6. New York Times, “Trump Threatens ‘Fire and Fury’ Against North Korea if It Endanger U.S.,” 8 August 2017.

- 7. Trump, Donald.Twitter Post. August 11, 2017, 12.29PM.

- 8. BBC News, “Trump UN speech: Why his rhetoric was a game-changer,” 20th September 2017.

- 9. The Washington Post, “Tillerson, Mattis insist military options remain for North Korea,” 17 August 2017.

- 10. South Korea, U.S, China, Japan, Russia, North Korea.

- 11. Thomas Schelling, The Strategy of Conflict, (1960), pp. 16-17.

- 12. Sandeep Baliga, “Is an Unpredictable Leader Good for National Security?”, KellogInsight, Northwestern University, 19th June 2017.

- 13. Herman Kahn, On Thermonuclear War, Transaction Publisher, 2007.

- 14. The New York Times, “China Says Its Trade With North Korea Has Increased,” 13 April 2017.

- 15. Andrew Scobell, “China and North Korea Bolstering a Buffer or Hunkering Down in Northeast Asia?”, RAND Congressional Briefing, 8 June 2017.

- 16. The Guardian, “North Korea: US Sanctions Resolution Watered Down Before UN Vote”, 11th September 2017.

- 17. Samir Puri, “The strategic hedging of Iran, Russia and China: Juxtaposing participation in the global system with regional revisionism”, Journal of Global Security Studies, 2:4 (2017).

- 18. Lora Saalman, “Balancing Chinese Interests on North Korea and Iran”, The Carnegie Papers, Carnegie-Tsinghua Center for Global Policy, April 2013, p. 1.

- 19. The Guardian, “Xi Jinping says a dark shadow looms over the world after years of peace,” 3 September 2017.

- 20. See, for example, President Moon’s speech at the Korber Foundation. The Korea Herald, 7th July 2017.

- 21. Although it must be said that some countries have themselves dismal human rights records. NGOs can be involved in addressing the human rights violations.

- 22. Also recognizing these limitations, the U.S. House of Representatives has recently passed ‘Otto Warmbier Act’ to cut off North Korea’s access to the global financial system. It is intended to ban entities conducting business in North Korea from dealing with US firms.

- 23. Cheon Seong-Whun, “Managing a Nuclear-Armed North Korea: A Grand Strategy for a Denuclearized and Peacefully Unified Korea,” Asan Issue Brief, 15th September, 2017.

- 24. Yonhap News Agency, “South Korea not mulling anymore THAAD deployment: foreign minister,” 30th October 2017.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter