The world is engulfed in COVID-19, but we can hope the global pandemic will be over not in a distant future with the development of vaccines and treatments.

In today’s reality, the most fundamental and serious threat is the North Korea’s nuclear program. This issue first arose in September 1992 when the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) raised suspicions about it.1 The situation has only deteriorated over the past 30 years. North Korea has advanced its nuclear capabilities with six nuclear tests, and continued development of new strategic weapons, including the North Korean version of Iskander, the North Korean version of the Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS), a new super-sized missile, a submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM), and an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). The situation is more dangerous than ever. Absent the North Korean nuclear threat, South Korea would have much less to worry about; it may even stay as a neutral country like Switzerland. The North Korean nuclear issue is not a fire across the river, but a fire at one’s doorstep. It would be nice if we could solve this problem on our own, but in reality, this is difficult. To solve North Korean nuclear problem, we need attention and cooperation of like-minded liberal democratic allies, supported of the United Nations (UN), being established to maintain global peace and stability, and cooperation with our neighbors—China, Russia, and Japan. Adding to the predicament of this challenge is that China and Russia openly support North Korea; the trilateral linkages among North Korea, China, and Russia are quite formidable. Unilateralism of great powers like the United States and China, which has become more common place over economic and security matters over the past several years, has made it more difficult to resolve the North Korean nuclear issue, and has intensified confusion in the international community by causing the rift of the liberal democratic alliances and the fading effect of partnership. As we anticipate the renewal of U.S. multilateralism under President Joe Biden, many are asking if this will bring us closer or distance us further from a resolution of the North Korean nuclear issue.

Figure 1. The North Korean Version of the Iskander

Source: Reuters

Existing global order is showing signs of collapse, but there is no new order to fill this void. Since World War II, the United States has established and maintained norms and order as the world’s police state. However, President Donald Trump moved to reorient the United States away from this role with his call for unilateralism and blatant repudiation of international norms. In the era of President Xi Jinping, China has declared its intention to realize the “China dream,” which envisions it as the center of the world. Within this world, China can dictate its own rules while coercing other countries to serve its interests. As Biden takes office, the revival of a U.S.-centered order will be tested not only by China but by chaotic conditions still gathering force. The U.S. and China are hardly outliers. Russia and France also took steps to promote their own narrow interests and form relations of convenience. The rise of unilateralism among great powers is likely to intensify confusion and anxiety in the international community. If organizations, such as the United Nations, are allowed to perform their proper role, there might be some hope. However, the UN has displayed inability and degradation through its failed management of the North Korean nuclear crisis and Libyan civil war. Inability and hollowing out of international and regional institutions have only raised the level of anxiety around the world.

It is not yet clear how the new Biden administration will break from the unilateralism of the Trump era, restore the alliance, and solve the North Korean nuclear issue with strong determination. It is difficult to predict whether the incoming administration will revert to what some demean as the strategic patience of the Obama administration, or whether North Korea will be recognized as a nuclear state through arms control as demanded by North Korea. The latter option is only a short-term solution that would lead to a terrible end. In order to cope with the North Korean nuclear program, the desired pathway is to work closely with our ally, the United States, and cooperate with Japan, China, and Russia. Support from the UN is also critical. Countries cry out for peace, safety, and international law, but the harsh reality is that countries act in strict accordance with their own narrow national interests. International organizations have hollowed out, international norms and order have deteriorated, and alliances among liberal democratic nations are in danger of breaking. This chaotic world is pushing our survival and prosperity to the edge of the cliff. We must recognize this trend and prepare to address these challenges in 2021.

■ Reviewing 2020

Disarray from “COVID-19” and U.S.-China Strategic Competition

The world that unfolded before our eyes in 2020 was both familiar and unfamiliar. The trade dispute between the U.S. and China and the strategic competition that existed had been ongoing since the mid-2010s. But we saw a qualitatively different pattern in 2020. To be more precise, the United States and China began to see each other as threats and an existential challenge. The rivalry was beyond strategic competition, suggesting the possibility that they could do away with norms of checks and balance within the context of interdependent relations. It was shocking to hear the oft-volatile President Trump stating publicly in May that he is willing to “cut off the whole relationship”2 as the rivalry began heating up.

The U.S. and China have begun to talk about the possibility of living in two different worlds depending on circumstances surrounding the nature of the competitive relationship. In 2019, the U.S. demanded the exclusion of Chinese technology and operating systems (i.e., Huawei) from other countries and followed through with the recent announcement to expel Chinese-owned SNS applications, such as ‘TikTok’ and ‘WeChat,’ from the U.S. market. This case illustrates how the U.S. can build a great firewall against China. Competition between the U.S. and China is now expanding beyond the nation-state level to encompass the international level.

Figure 2. South China Sea, the Frontline U.S.-China Strategic Competition

Source: CSIS.

The U.S.-China strategic competition does not explain everything about global trends in 2020. Other countries did not respond passively to these changes. They made use of the opportunities from the strategic competition between the U.S. and China to expand their influence at the global and regional level. The most notable is Russia, which has emerged as a rival to the United States to push its illiberal agenda predominantly in the Middle East and “the near abroad” regions. Turkey ostensibly emphasized Islamic values, but also strongly expressed authoritarianism, which was an important factor in the geostrategic shift in the Middle East. Countries in the Middle East have also begun to redefine their relationship with Iran and Israel, which marked a significant break from tradition and norms. The European Union (EU) started from a siloed approach to the U.S.-China competition, if by year’s end some major states were revisiting their ties to China and beginning to ponder increased linkages to countries in the Indo-Pacific region amid the chaos of Brexit.

Figure 3. Huawei Has Been Designated by the U.S. for Sanctions Violations

Source: Yonhap News.

The COVID-19 pandemic magnified the prevailing global trend in 2020. Most of the above-mentioned phenomena were present before the spread of the virus. However, COVID-19 acted as an agent to elevate the visibility of reconstituting global order, which previously was opaque. When COVID became a global crisis, the United States and China ran against the cooperative spirit of globalization and digitalization. Both were responsible for failing in exchanging information related to the spread of COVID-19 or cooperating for the development of treatments and vaccines. In March, for instance, when COVID-19 was rapidly spreading around the world, each sought to transfer blame, arguing even that the rival’s system rather than any policy was the catalyst for the pandemic, precipitating the intensification of the strategic competition. International organizations, such as the World Health Organization (WHO), lost their credibility as a linkage mechanism or center of global joint response, and it is doubtful whether they can continue to play that role in the future.

Even if reliable vaccines and treatments are developed, a return to pre-COVID-19 normalcy will be difficult. Neither the United States nor China has been able to establish itself as the global agenda setter. They have also fallen short of establishing best practices for other countries to follow. Similar lack of leadership extends beyond COVID-19. Countries have begun to question whether the world pursued by either the United States and China will be safer and more prosperous than before. To make matters worse, existing regimes and international organizations also have weakened authority and power. There is no clear cause or goal to bring other countries together. There is growing anxiety that existing order may no longer promote global prosperity or stability. This is because the events of 2020 have sowed seeds of doubt and questions about the suitability of an acceptable alternative to the pre-existing order.

Figure 4. COVID-19 Vaccination

Source: Reuters.

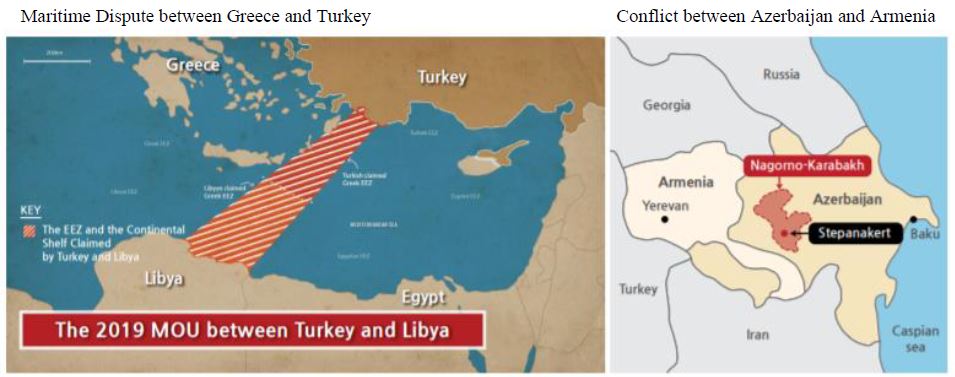

The weakened credibility of international regimes and international organizations is not limited to WHO. In 2020, the United Nations failed to solve the Greek-Turkish maritime dispute over the delimitation of the exclusive economic zone and continental shelf.3 The Azerbaijan-Armenian conflict over the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh4 has not been fully resolved.

Figure 5. Dispute between Greece-Turkey and Dispute between Azerbaijan-Armenia

North Korea’s Nuclear Issue and an Hollowing out of UN

The UN, which can be a small hope in chaotic world, has largely been powerless in introducing and enforcing necessary sanctions against North Korea to resolve the North Korean nuclear problem.

The North Korean nuclear problem has continuously deteriorated over the past 30 years, and North Korea’s nuclear capabilities have only improved over time. The North Korean nuclear program is fundamentally different from that of Israel, India, and Pakistan, which were programs outside the purview of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). Although these countries are not members of the NPT, they profess that they will not proliferate nuclear weapons, advocating respect for the basic principles and objectives of the NPT. Unlike these countries, North Korea is the only case of a member of the NPT abandoning its nonproliferation obligations and secretly developing a nuclear program. It has shaken fundamental pillar of the non-proliferation regime. The North Korean Constitution and the Workers Party Program both claim that North Korea is a nuclear power, and it seeks to be recognized as a nuclear state. Currently, North Korea has 40 to 60 nuclear weapons; one of the dangers that it poses is production and export of fissile materials into other regions, such as the Middle East. There is also the potential for proliferation within Northeast Asia. A senior U.S. official said in an interview at the Asan Institute for Policy Studies that if North Korea does not denuclearize, South Korea, Japan, Vietnam, and Taiwan have the ability to possess nuclear weapons within a year.

When North Korea first declared its intention to withdraw from the NPT on March 12, 1993, it did not fulfill its obligations under the treaty. Article 10, Paragraph 1 states that a country wishing to withdraw from the NPT must notify all treaty parties and the UN Security Council three months prior to withdrawal. North Korea had to accept IAEA inspections until its withdrawal from the NPT was official, but it failed to do this. Nevertheless, the UN did not impose any penalties against North Korea for this violation. On October 21, 1994, North Korea returned to the NPT according to the “‘Agreed Framework between the United States of America and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (Agreed Framework),” but neither the UN nor any of the neighboring countries pointed to North Korea’s misconduct. When North Korea declared its second withdrawal from the NPT on January 10, 2003, the response from the UN was also passive. Although North Korea took measures to restart its nuclear facilities and neutralize the IAEA’s surveillance and inspections without any advance notice as of 2002, the UN did not issue warning and introduce any sanctions against North Korea.

UN Security Council Resolution 1695 marks the first time that the UN has imposed sanctions against North Korea’s nuclear program, which was issued only after North Korea conducted a long-range missile test in July 2006. This was more than 13 years after North Korea’s first declaration of withdrawal from the NPT; but the measure fell far short of sanctioning North Korea’s nuclear development. North Korea conducted its first nuclear test on October 9, 2006, as if to ridicule the UN response, in violation of the September 19, 2005 Joint Statement of the Six Party Talks.5 Even though North Korea continued with its second and third nuclear tests in 2009 and 2013, the UN failed to adopt resolute sanctions and enforcing them to denuclearize North Korea. The UN sanctions against North Korea at each of these junctures were limited to a small number of organizations or individuals directly related to the North Korean military. The measures fell short of influencing the civilian sector, which is the financial backbone of the North Korean regime. This is an important difference from the Iranian case. Beyond UN sanctions, countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom, implemented strong unilateral sanctions, forcing the Iranian government to engage in serious denuclearization talks. If the strength of the sanctions regime against North Korea is 10, then the corresponding figure for the sanctions regime against Iran is 100. Major western countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Germany, felt threatened by the ineffectiveness of UN sanctions against Iran and came up with additional measures, which pressured Iran to accept negotiations.6 Prior to 2016, sanctions against North Korea were mainly about prohibiting transactions in materials related to nuclear and missile development, and only expressed concern about financial transactions with North Korea. Sanctions against Iran, which was led by the United States with European participants, focused on blocking Iran’s foreign financial transactions.

The introduction and enforcement of sanctions against North Korea began not in 1991, when the North Korean nuclear issue began to emerge due to the discovery of the Yongbyon nuclear complex, but 25 years later in 2016. Meaning and effectiveness of sanctions are far below the expectations. It was too late, too little. The UN is not free from responsibility for the North Korean nuclear issue. Other western nations also share some of the blame for failing to act as they did in Iran.

Despite reinforced sanctions against North Korea, it is questionable whether existing measures are adequate. Above all, China and Russia continue to support North Korea by bypassing or avoiding sanctions. According to a 2019 report of the Panel of Experts of the UN Security Council Sanctions Committee on North Korea, large-scale inflows and outflows of goods through illicit ship-to-ship transfers were occurring in North Korea, and the amount of illegal trans-shipments included 57,000 barrels of refined petroleum products (worth KRW 6.4 billion).7 On March 9, 2020, The New York Times quoted a 2020 report of the Panel of Experts, which stated North Korea continued to export coal and sand in exchange for luxury goods such as bulletproof cars, alcohol, and precision machinery via China and Russia.8

China and Russia have argued that sanctions against North Korea may jeopardize the North Korean “people’s livelihoods” and cause humanitarian problems. They have continued to take negative stances on strengthening sanctions against North Korea. The United States also advocated strong unilateral sanctions, but this is not sufficient. In order for the U.S. sanctions on North Korea to be effective, it is important to continually update the entity list, but this was put on hold because of Trump’s attempts to engage with Pyongyang. It is reported that President Trump, who still wanted the resolution with North Korea, rejected the update of the list and actually banning financial transaction prepared by Treasury Department.

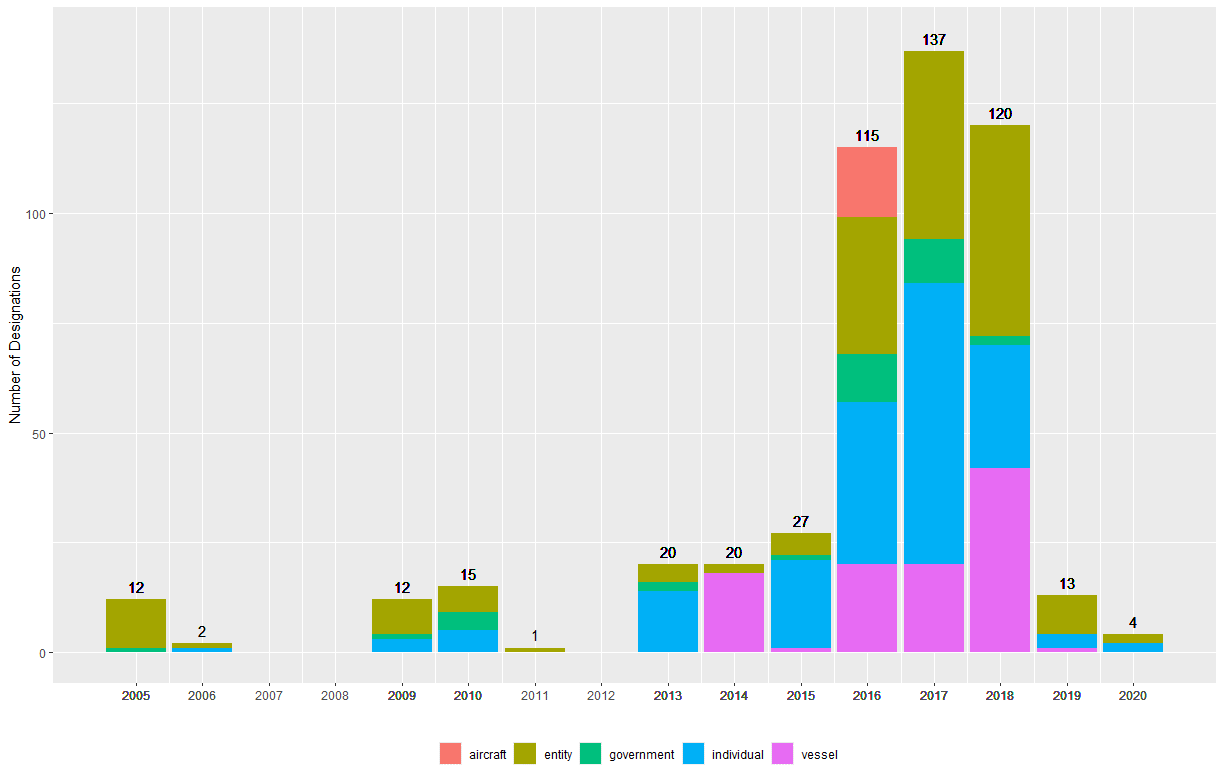

Figure 6. U.S. Treasury’s DPRK Sanction Designations, 2005-2020

Source: OFAC SDN.

The problem is that North Korea’s nuclear capabilities are growing while sanctions against North Korea are less than adequate. Experts estimated that the number of nuclear warheads in North Korea was about 10 to 15 in 2015. According to North Korea intelligence experts including DIA analysts, intelligence estimates in 2017, however, suggest that North Korea could have up to 60 nuclear warheads. If this trend continues, the number of North Korean nuclear warheads could be more than 100 by the early 2020s. North Korea can threaten South Korea without any hesitation and South Korea is in a situation, where it is a “nuclear hostage” of North Korea.

■ Era of Chaos: New Cold War and Decline of International Order

The main reason that the “New Cold War” was selected as the theme for this year’s 2021 outlook was that the preconditions in 2020 were similar to those of the Cold War. The emergence of a great power (i.e., China) that challenges the existing order raises fear in an established power (i.e., the U.S.), creating conditions ripe for competition and confrontation which may result in the “Thucydides Trap.” Of course, in the era of global interdependence, this development might lead to mutual destruction; hence, this outcome is unlikely. However, if distrust continues to grow and bilateral relations are not managed properly, antagonism, confrontation, and conflict will only increase, making the world more unstable and dangerous.

In 2021, the collapse of international norms and order as we know it threatens to become even more apparent. As shown in the U.S.-China strategic competition and Russia’s growing influence, mutual checks between liberalism and illiberalism as well as liberal democracy and authoritarianism are becoming increasingly evident. This trend is reminiscent of the confrontation between the U.S. and the Soviet Union after World War II and has accelerated as a result of COVID-19. In the past, confrontation among great powers often resulted in a balance of power rather than complete annihilation of the other. During the Cold War, the blocs led by the U.S. and the Soviet Union aimed for victory over the other and the dissolution of hostile ideologies and systems, but they had to accept “peaceful coexistence” in the interim. Trump’s approach was full of contradictions, at times embracing Xi Jinping and anticipating a transaction that would allow him to claim a great victory on trade and reelection in 2020, and at other times attacking China’s system beyond what any U.S. president since Richard Nixon had done. There was no strategic consistency, but the direction grew more confrontational. His administration seized on the pandemic to blame the root cause on China’s ideology and system of governance. Since the global financial crisis of 2008, China had also been casting blame on U.S. ideology and a flawed system of capitalism, reinforced by Xi Jinping’s appeal to socialism and insistence that U.S. foreign policy is rooted in ideology not national interests. As the Trump camp ratcheted up its aggressive rhetoric, the new “wolf warrior” activism in China doubled down on inflammatory rhetoric of its own. The U.S. has taken the initiative of establishing what could become a NATO-like organization in Asia by launching its “Indo-Pacific Strategy” through the “Quadrilateral Security Dialogue” (Quad) or “Quad Plus” initiatives. Under the Biden administration, the U.S. will accelerate the creation of a U.S.-led cooperative network through a Summit for Democracy and the restoration of its alliance relations. China will also continue to expand its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in order to broaden its sphere of influence. The Cold War was essentially a systemic competition grounded in an ideological confrontation between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. In the military domain the manifestation of this competition was an arms race involving both nuclear and conventional forces. In many ways, the current competition between the U.S. and China is similar; however, the New Cold War is different from the old one in several significant ways, which we discuss in the following sections.

National Interests before Ideology

One distinctive feature of the Cold War was the ideological battle between capitalism (liberal democracy) and a command economy (communism). Blocs were formed according to this ideological competition, and both camps placed significant emphasis on promoting the spread of their own ideology and containing the rival ideology. Sometimes, ideology superseded national interest. Generally, states act according to their interest; however, ideological thinking at times precluded interests from determining policy during the Cold War era. Modes of economic dependence illustrate this point quite nicely. During the Cold War era, economic cooperation was closer to “aid” than “trade.” A prime example is the support that the United States provided to developing countries to promote capitalism and democracy in exchange for little or no material benefit. However, the U.S. overlooked the absence of democracy when its national interests or Soviet expansionism were at issue, as in the Nixon opening to China.

Ideology is not a critical determinant of relations in the New Cold War era. Although the United States is critical of China’s violation of human rights and international law, Washington has been less than consistent in how it applies this standard to other countries around the world. For instance, the U.S. moved to improve relations with Myanmar, which is accused of committing systemic genocide against the Islamic Rohingyas. China also does not make a distinction between capitalism and socialism nor in excluding free democratic countries from participating in BRI or the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). In this respect, ideology is a criterion for discriminating for and against different states, but it is not a key determinant of cooperation. This trend will continue.

Fight Over Hegemony and Profiteering Cloaked in Values

Existing system and international regime were damaged in 2020. Sometimes, attempts were made to abandon or replace the existing weakened regimes encroached upon by opposing powers. The US withdrawal from WHO is an example. In other words, there is a risk that international governance regime can be used as a means to guarantee hegemony instead of delivering peace and prosperity for all. At this time, it is unclear whether trend will change under a new US administration. China and Russia will not hesitate to form a new regime or fight over control of the existing regime.

Within the framework of this competition for global governance, the two sides will focus on debates about desired values rather than wage ideological battles as they have in the past because such approach will make it easier to gather more countries and to justify actions. The United States and Western countries have their core values of freedom, democracy, human rights, market economy, and the rule of law. China also insists on freedom, equality, democracy, and rule of law.9 But it also emphasizes the values of state and society by advocating for prosperity, civilization, harmony, patriotism, and friendship. In foreign policy, the value of sovereignty and territory, non-interference in internal affairs, anti-hegemony, and multilateralism are also held in high esteem.10 At first glance, the values pursued by the US and China appear similar. However, each make different claims about the interpretation of these values. The U.S. and Western nations observe democratic governance in which free election system functions properly and check and balance is observed through separation of power. In authoritarian regime like China, that rests on one Communist party rule, state, society, and individual are subservient to the Communist Party. Freedom of expression is one of the centers of battle of value between the US and China. The US sees freedom of expression as an essential pillar of democracy while China sees it as a privilege which should be subsumed under majority interest and social order. The conflict between the US and China over this is likely to intensify.

Democratic institutions must function properly in order for values to be properly embodied and to be centered around values. Democratic institutions, however, may fall into the populist trap, or the façade of democracy hides the monopolization of power by a small group within. Japan is a good case in point. Free elections are guaranteed in Japan, but the Liberal Democratic Party has been the dominant ruling party for much of Japan’s political history.11 Robert A. Scalapino of Berkeley University, refers to Japanese politics as the “1.5 Party System.” His point was that Japanese politics was completely dominated by the LDP with a handful of weak opposition parties that amounted to half a party in terms of its combined influence. Some experts say that the United States is the real opposition party in Japan, but today even the US seems to have joined the ruling LDP coalition. If Japanese domestic politics falls in to the collapses of check-and-balance caused by the LDP’s long-standing dominance is not desirable for peace and prosperity in East Asia.

One thing is certain, the clash of values surrounding global governance will become an ever more ingrained and distinctive feature of the New Cold War era. Whereas the Cold War was a confrontation between freedom (i.e., capitalism and liberal democracy) and control (i.e., communism and dictatorship), the New Cold War implies a world which openly emphasizes value but outrightly champions national interests. There is a risk that this kind of world can lead to the collapse of global governance and usher in an era of chaos.

Opaque Spheres of Influence

Given that the New Cold War will be driven by competition over national interests and governance, the spheres of influence among great powers are likely to become fluid. COVID-19 has been a countercyclical force against globalization and information flow. Recent restrictions on immigration and information sharing by countries are illustrative. However, overlapping interests in vaccine development and the race to secure necessary medical equipment, such as masks, have shown that it is impossible to completely reverse globalization and information sharing. As long as this continues, formation of separate blocs as in the Cold War is unlikely.

In the age of a New Cold War, active engagement and expansion in other spheres of influence are bound to be common because cooperation and competition among countries can be reversed any time if its suits national interests and/or governance. Competition for expanding influence is gaining momentum with the emergence of China’s BRI and the U.S.-led Indo-Pacific Strategy and Quad initiative. There are likely to be three possible domains of bloc formation: 1) the traditional security and military domain is where separation is clearest and physical barriers are likely to strengthen; 2) the governance domain is where bloc formation is likely to be most blurred; and 3) the technological domain, which includes 5G and artificial intelligence (AI), is where new blocs may form within the digital space centered around distinct core technologies and platforms. Competition in the technological domain is expected to be especially fierce as the U.S. and China intensify their efforts to achieve technological superiority and negate the rival’s capacity.

Weakening Cohesion of Alliances and Blocs

The “hybrid geopolitics” concept introduced in the 2020 Asan Global Security Outlook mentioned the phenomenon of fluid alignments and blurred spheres of influence. This implies that the cohesion of old blocs would have little efficacy in the New Cold War. Depending on disparate interests, countries may take part in U.S.-led spheres for certain issues while strengthening cooperation with anti-U.S. and antiWestern powers on other matters. During the Cold War, cooperation with adversaries was nearly impossible. This is because any sign of cracks in bloc cohesion could be construed as abandonment or necessitate direct intervention under the “Brezhnev Doctrine.” However, the range of options available for countries may be rather broad when neither the U.S. nor China is able to monopolize international legitimacy. That is, while countries may face some dilemmas over alignments, they are also able to take advantage of the fluidity in movement across blocs depending on the situation and context. For most countries with limited power, concerns over their autonomy may be aggravated. Aside from China and the U.S., countries may be driven less by commitment to any one side and more by survival instincts; at times, this trend may even encourage multilateralism.

All-round Competition and New Arms Race

The New Cold War will continue to accelerate in 2021. Each country will have to plan a strategy for survival and prosperity in this new age. In 2020, the New Cold War emerged in various spheres, including trade, technology, and geopolitics—a range that differs from the past Cold War. Although the world was able to avoid World War III, the apparent conflict among political and economic power blocs during the Cold War era manifested itself in a competitive arms race. Competition during the New Cold War era, however, is not likely to be confined to military power; rather it is likely to expand into the private sector. Sometimes, conflict can be linked to flux in the global supply chain. Under this condition, states would need to consider abandonment and entrapment in both public and private sectors when making policy decisions.

An all-round competition in the military domain implies a perpetual arms race. During the Cold War, the nuclear arms race was coupled with a conventional one. The “nuclear balance of terror” prevented global wars and enabled arms control. During the New Cold War, however, major powers will try to gain supremacy to overwhelm or prevent the adversary from achieving parity through developments in spaces outside of conventional and nuclear capabilities to include unmanned technology and robotization, as well as hypersonic weapons and space power. This will raise the burden of defense spending and usher in an infinite arms race. Coupled with this change will be an expanded effort to establish and reinforce networks among likeminded countries by strengthening operational connectivity. This kind of development is likely to raise the risk of transforming the U.S.-China strategic competition into a “Thucydides trap.”

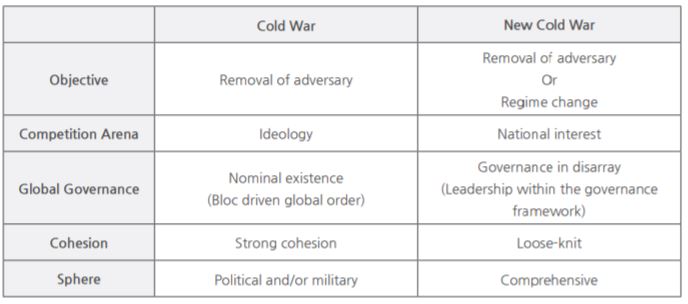

Table 1. Cold War and New Cold War

■ Outlook on 2021

The defining features of the New Cold War in the era of chaos are likely to be more pronounced in 2021. The debate on the responsibility for the spread of COVID-19 has shown that the United States and China cannot genuinely coexist in peace; the only way for peaceful coexistence to work is transformation or subservience of the other. This trend will become even more apparent in 2021 depending on the contours of the U.S.-China competition coupled with the emergence of new military capabilities and efforts to expand the influence of anti-U.S./ western values as well as the choices that countries make.

Having reviewed the Trump administration’s foreign policy, the Biden administration is likely to restore U.S. leadership, but its overall strategic approach towards China will not fundamentally change. The Biden administration is also likely to reengage with multilateral regimes, such as the Paris Agreement, which the Trump administration abandoned and intensify the fight over values through such mechanisms as the “Summit of Democracies.” Restoration of international rules, norms, and institutions will move forward as the U.S. offensive against China gains momentum in the areas of science and information technology (i.e., 5G and AI) while cooperation among the anti-China coalition of the Quad and Quad Plus will also become more pronounced. In recognition of Russia as China’s partner, the U.S. will move swiftly to engage in the New START negotiations while simultaneously entering into an arms race.

China is continuing to strengthen Xi Jinping’s power and intensify political indoctrination in nationalism. While implementing the “14.5 Plan,” which is centered around the “dual circulation” development strategy12 and self-reliant science and technology, China will attempt to expand domestic demand, promote qualitative growth, and accelerate the formation of an independent technology platform. Amid such competition, conflict with the Biden administration is likely to become more frequent on issues related to China’s “core interests,” such as Taiwan, Hong Kong, Xinjiang, and the South China Sea. China will try to contain the U.S. and consolidate its control in the region by exploiting economic interdependence and expanding non-traditional security cooperation with U.S. allies, like Korea and Japan. If this is not effective, Beijing can resort to the use of economic pressure.

Russia is likely to cooperate with China while continuing to expand its influence in the region where the regional order is in flux. Russia, which recognizes that it had already entered the New Cold War with the United States during the Obama years, is likely to further accelerate its effort to exploit the gaps in the U.S.-China competition. Japan is likely to focus its diplomatic efforts on successfully hosting the Tokyo Olympics, which will be its most significant event in 2021. Manifestation of this policy may come in the form of “selective solidarity” or “hostile coexistence” with neighboring countries under the broader framework of the U.S.-Japan alliance, which will be based on “principles” and “interests.” Under this arrangement, Japan is likely to engage in a twofaced diplomacy to manage relations with China while working with the United States.

Attention will be paid to the EU’s choice in 2021. While welcoming the Biden administration’s restorative approach to alliances, many EU member states are likely to maintain a different position on technology and 5G (i.e., Huawei). There may be disagreements with the U.S. on issues related to NATO as well. Like the pressure from President Trump, President-elect Biden is also likely to demand NATO member states spend two percent of their gross domestic products (GDP) on defense. This illustrates the characteristics of the New Cold War, which prioritize national interests in the process of restoring the U.S.-NATO alliance. Even as a member of NATO, Turkey’s insistence on walking its own path on the Middle East and Russia is also likely to continue.

U.S.-Russia competition is likely to be more front and center in the Middle East. The vacuum left by the U.S. exit and rise of Russian influence in the Middle East has ushered in a period of mixed results under Trump’s watch. His “America First,” neo-isolationism, and transactional approach to alliances have damaged U.S. standing and relationships in the Middle East, which will be difficult to repair. Russia and China are unlikely to relinquish any gains that they have made in the region in terms of their influence. The axis of revisionist powers in Russia, China, and Iran will grow closer to maintain regional influence. Countervailing forces will make it difficult for the U.S. to reverse this trend and the outlook for Libya in North Africa is not ominous.

In Southeast Asia, the Biden administration will likely attempt to contain China’s influence by getting closer to the regional partners. Expect to see more quality strategic and economic engagement within the multilateral regional framework. This, however, does not necessarily imply that ASEAN nations will make a meaningful shift toward the United States. Instead, the region will use this strategic opportunity to better address the COVID-19 challenge while extracting more economic aid from China. Southeast Asia will be hot spot of the New Cold War, and the region will want to keep it this way throughout 2021 because this is the ASEAN Way of managing this challenge.

While the New Cold War presents various challenges, this year’s Strategic Outlook places special emphasis on scientific and technological competition as well as liberal democracy in crisis. We see a continuing trend where the U.S. and China will both seek to accelerate their efforts to expand digital hegemony through platform and data dominance in 2021 and beyond. Areas such as semiconductors, space technology, and quantum computing can emerge as new domains of conflict; realignments as a result of technological decoupling can be a source of confusion and instability.

Given that ideology is less significant in the New Cold War era, we need to acknowledge the reality that a major power will be less interested in promoting or restoring liberal democracy in other countries. Instead, the rise of right-wing populism during the information age can hasten the decline of liberal democracy. This trend can continue even as the U.S.-China competition gains momentum around values and interests thereby deepening the crisis of liberal democracy and elevating the emergence of authoritarianism.

The Biden administration prioritizes principal foreign policy for restoring alliances, promoting democracy and human rights, and participating in multilateral institutions; but there are limits to what it can do to prevent the decline of international rules and order as well as the hollowing out of international regimes. The United States must work with liberal democratic forces as well as seek to enlist China and Russia at times, by no means an easy task as we can see in the case of civil war in Libya.

There are distinct challenges for South Korea in the era of chaos and New Cold War. Due to North Korea’s nuclear weapons and missiles, our security is under serious threat. Proper responses to this threat require cooperation with liberal democratic allies and neighboring countries as well as support from the UN. It is unrealistic for South Korea to expect help from China and Russia, which stand with North Korea. It is also unclear whether the Biden administration will uphold the NPT and actively strive towards denuclearization of North Korea as it seeks to break from the “America First” policy of the previous administration. Unclear too is how much China will cooperate with South Korea as it seeks to pursue the China Dream. It is also questionable whether Japan will cooperate with South Korea when bilateral relations are challenged due to outstanding historical issues. Countries each pursue their interests. Our survival and prosperity are threatened as global order is collapsing, alliances are under stress, and international organizations are hollowed out to usher in a period of disarray. 2021 will demand greater vigilance from South Korea.

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 1. In September 1992, the IAEA found a difference between the amount of reprocessed plutonium reported by North Korea and the amount estimated through inspection, and it requested clarification and acceptance of special inspections. The first nuclear crisis began as North Korea rejected special inspections and declared its intent to withdraw from the NPT in March 1993. “Chronology of U.S.-North Korean Nuclear and Missile Diplomacy,” Arms Control Association, last modified July 2020, accessed December 21, 2020.

- 2. “Trump on China: ‘We could cut off the whole relationship,’” Fox Business, May 14, 2020.

- 3. In November 2019, Turkey agreed on a memorandum of understanding with the western Libyan regime to delimit the maritime boundaries of the two countries in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. This MOU established only one straight line in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea, stretching about 18.6 nautical miles. It was only a straight line, but it ignored the maritime entitlement of Greece and Egypt to the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf. Turkey disregarded Greece’s claim and mobilized its frigates in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea to engage in exploration activities. On August 12, 2020, an “accident” occurred in which Greek and Turkish frigates collided in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. The UN has done little to resolve this maritime dispute. On June 9, 2020, Greece signed an agreement regarding the delimitation of the exclusive economic zone with Italy in the “Ionian Sea,” and on August 6, 2020, another agreement with Egypt in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea to countervail the 2019 MOU between Turkey and the western Libyan regime.

- 4. On September 27, 2020, the battle between Azerbaijan and Armenia over the Nagorno-Karabakh region began. The Nagorno-Karabakh region, which is an Azerbaijani territory under international law, has effectively been controlled by Armenia. The region has been in conflict since 1992. Azerbaijan and Armenia achieved independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, but in 1992 the parliament of the Nagorno-Karabakh region, located within the territory of Azerbaijan, declared the creation of an independent republic. The new parliament declared that it would pursue integration with Armenia. The resulting conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia continues to this day. In response, the international community, led by the United States, Russia, and France, has attempted to resolve this dispute. But these efforts have only confirmed existing divisions among these countries. Turkey supports Azerbaijan for ethnic and religious reasons; France supports Armenia because France is the largest country in Europe where Armenian immigration groups have settled. Eventually, through the armed conflict in 2020, Azerbaijan recovered most of the disputed areas by force, and through a peace agreement signed on November 9, 2020, Russia decided to deploy peacekeepers for the next five years with the withdrawal of Armenian forces. The Nagorno-Karabakh dispute was in fact settled through the use of Azerbaijani force. The powerlessness of international organizations, including the UN, was proved once again.

- 5. In the Joint Statement of the Fourth Round of the Six-Party Talks agreed by representatives of South Korea, North Korea, the United States, China, Japan, and Russia, North Korea agreed to give up all nuclear weapons and dismantle existing nuclear programs in order to achieve verifiable denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula in a peaceful manner and prohibit nuclear proliferation as soon as possible. It pledged to return to the NPT and abide by the IAEA safeguards.

- 6. The key to sanctions against Iran by Western countries, including the United States, was to freeze Iranian assets in the country and block Iran’s international financial transactions.

- 7. According to The Wall Street Journal, North Korea illegally exported about 4.1 million tons of coal to China between January and September 2020. It is said that they made about $10 million in foreign currency. It is also reported that China employs about 20,000 North Korean workers, in violation of UN sanctions. “Covert Chinese Trade with North Korea Moves into the Open,” The Wall Street Journal, December 7, 2020.

- 8. “Armed Cars, Robots and Coal: North Korea Defies U.S. by Evading Sanctions,” The New York Times, March 10, 2020.

- 9. In 2012, the Chinese Communist Party proposed and adopted 12 values, including fairness, professional spirit, integrity and trust, as core socialist values at the 18th National Congress. In 2013, the CCP published <Opinions on the Cultivation and Practice of Socialist Core Values>, emphasizing education and practice of those values.

- 10. China has taken the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence as its core foreign policy. The five principles are: 1) mutual respect for territorial sovereignty, 2) mutual inviolability, 3) mutual non-interference, 4) equal reciprocity and 5) peaceful coexistence. This was first proposed by Prime Minister Zhou Enlai on behalf of the Chinese government in a negotiation with India in December 1953.

- 11. As of December 2020, the Liberal Democratic Party of Japan has 283 seats in the House of Representatives, while the Komeito Party, which is part of the ruling coalition, has 29 seats. Together, the ruling coalition makes up about 67% of the 465 seats. The largest opposition party coalition, including the Constitutional Democratic Party and the Social Democratic Party, have 113 seats accounting for 24% of the parliament.

- 12. The “14.5 Plan” is China’s 14th Five-Year Economic Development Plan, which was passed at the 19th Plenary Meeting of the 5th plenum of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party in October 2020.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter