Dependencia, North Korea Style

Ever since the end of the Cold War the Sino-DPRK relationship has been the main external buttress helping to prop up the North Korean regime. Beijing has long provided its treaty allies in Pyongyang with economic sustenance and international support in exchange for border stability (and possibly other benefits as well). It is therefore striking that Pyongyang has recently taken to disparaging its partner in this vital relationship.

Amidst the pageantry surrounding the December 2013 purge and execution of Kim Jong Un’s uncle, Jang Song Thaek, North Korean officialdom accused Jang of “treachery” for “selling off precious resources of the country at cheap prices” — a thinly veiled reference to his role in North Korea’s commerce with China. In March of this year, the South Korean newspaper Chosun Ilbo reported that a top North Korean military academy – purportedly Kang Kon Military Academy near Pyongyang — was displaying placards calling China a “turncoat and our enemy.”

In early June, New Focus International, a defector news service that relies upon unnamed sources within the North, claimed that in April the Central Committee of the Korean Workers’ Party, formally North Korea’s highest leadership body, had issued an internal decree: “Abandon the Chinese Dream!” The alleged document condemns China as a corrupt economy and a “bad neighbor,” and calls for “amplify[ing] the foundations of an independent economy” in North Korea.

And that anti-China drumbeat continues, even at the highest levels of state. Late in July, North Korea’s official press service, KCNA, ran a scathing statement by the spokesman for the National Defense Commission, which directs the DPRK’s armed forces. It blasted China for “joining in” the “odd charade” at the UN of condemning Pyongyang for its missile launches earlier that month. The spokesman then went on to mock Xi Jinping for his recently concluded state visit to Seoul: “Clinging to the malodorous coattails of the U.S., they are going so reckless [sic] as to vie with each other to hug poor-looking [South Korean President] Park Geun Hye.”

Viewed on its own, such harsh rhetoric may seem like a curious way to treat an ally that has long acted as one’s principal protector in the international arena, buffering North Korea from international criticism, pressure, and punishment. Viewed in conjunction with trade data on the Chinese-North Korean economic relationship, however, what emerges is a phenomenon entirely understandable and in fact quite familiar in other parts of the world: among them, Latin America, Africa, and the Middle East. Call it dependencia, North Korea style. Taken in context, Pyongyang’s tirade of complaints about Beijing reads very much like a classic case of ressentiment of a client state against the patron on which it desperately depends financially. And trade data underscore just how dependent on China Pyongyang actually is these days. China may currently provide North Korea with as much as 85 percent of its commercial imports, and account for over 75 percent of its commercial exports.

In the sixty-plus years since the Korean War armistice, North Korea may never before have been so completely dependent on the largesse of a single outside benefactor as it is on China today. As a result, Pyongyang can hardly help but focus on reducing the state’s fearsome current dependence on Beijing—and not just by issuing therapeutic official critiques of its enormous neighbor. To offset China’s current dominance over the nation’s international ledgers, Pyongyang should be expected to devise and unleash stratagems for extracting aid and politically conditioned trade from the other members of the Six Party Talks: Russia; Japan; South Korea—and yes, the United States as well.

Exceedingly very few hard facts on the performance of the North Korean economy are available in the outside world. The statistics Pyongyang itself releases are fragmentary and often untrustworthy. There is, however, one relatively reliable source: “mirror statistics,” so-called because they utilize the reports of North Korea’s trading partners to reflect the cost of goods that North Korea buys and sells, as opposed to actual trade reports from North Korea itself. This information is on “merchandise” trade: data for goods or commodities rather than “services.” (“Services”–things like travel, banking, or information technology—do not seem to figure appreciably in North Korea’s commercial interactions with the outside world, even though they now make up a considerable fraction of global trade overall). Those merchandise numbers provide a window to the country’s legitimate commerce, and a metric by which to gauge North Korea’s dependence on its trading partners. (Of course, such statistics exclude the illicit commerce of the counterfeit $100 notes, drugs, and weapons in which the DPRK infamously traffics.)

A picture of North Korea’s overall merchandise trade trends can be created by compiling reports from three sources: South Korea’s Ministry of Unification for reports on inter-Korean trade; the Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency for data on North Korea’s extra-peninsular imports and exports; and a United Nations database known as COMTRADE. Mirror statistics report what foreign partners pay, and are paid, for North Korean goods, rather than what the North Koreans earn or pay for the merchandise. It is then possible to derive an estimate of what North Korea gets or shells out for goods by taking into account and making adjustments for shipping, insurance, and other charges (so called FOB-CIF adjustments).

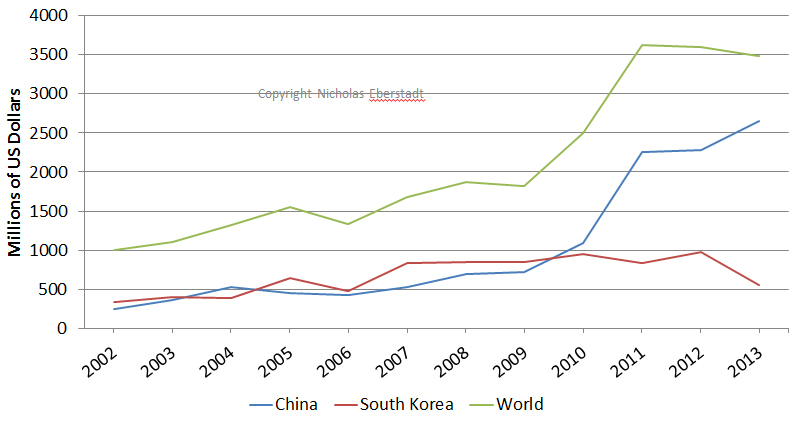

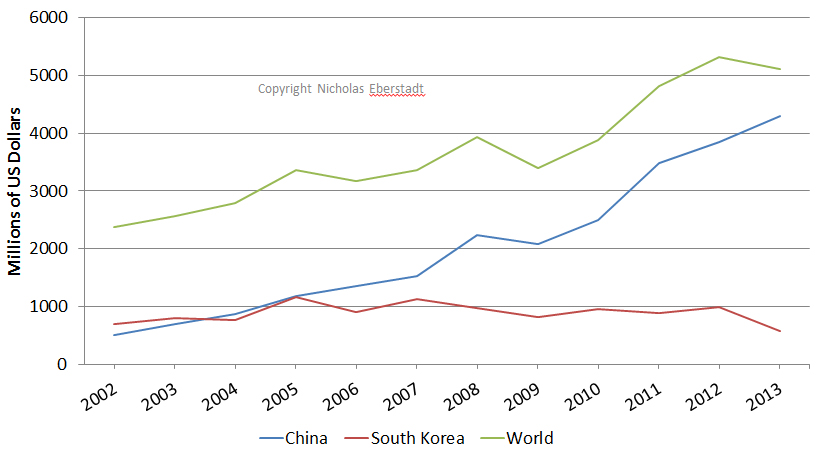

Measured in current U.S. dollars, estimated North Korean exports have more than tripled between 2002 and 2013, increasing from about $1 billion to about $3.5 billion. (Figure 1). Over the same period, estimated North Korean imports more than doubled, from about $2.4 billion to more than $5 billion (Figure 2). But the vast majority of that increase appears to have come from China. The remainder of the upsurge in North Korean trade during this period came from increased commerce with South Korea.

Figure 1. Adjusted North Korean Merchandise Exports, 2002-2013

(current $ US)

Sources: KOTRA, UN COMTRADE Database, ROK Ministry of Unification

Figure 2. Adjusted North Korean Merchandise Imports, 2002-2013

(current $ US)

Sources: KOTRA, UN COMTRADE Database, ROK Ministry of Unification

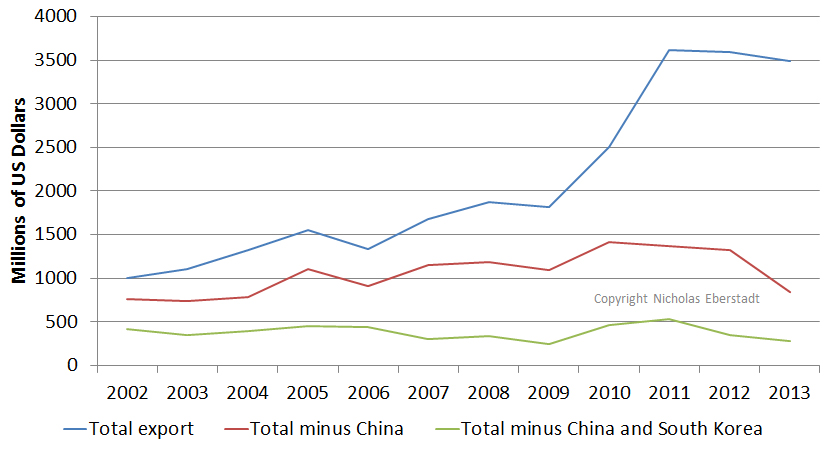

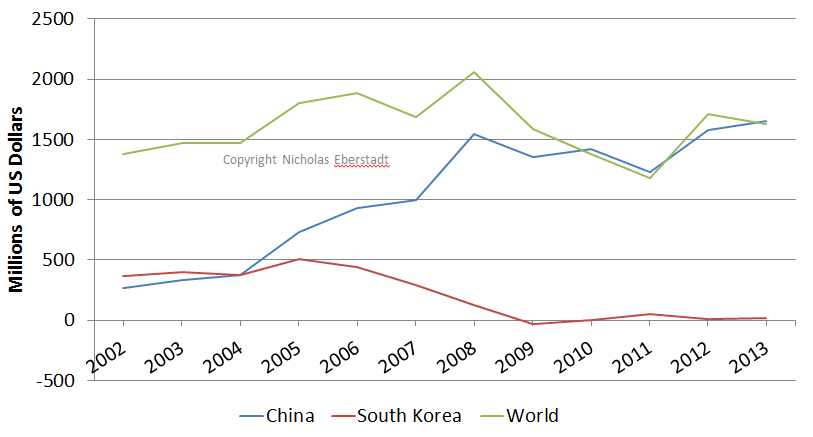

Breaking down the DPRK’s estimated exports and imports shows just how critical trade with these two nations has become to North Korea. Without China, North Korea’s estimated exports in current dollars are basically flat between 2002 and 2013. Factor out both China and South Korea, however, and North Korea’s estimated exports to the rest of the world are actually down sharply — $422 million in 2002 vs. $282 million in 2013, a drop of roughly one-third. Plainly stated, North Korea’s commercial exports to the rest of the world are minuscule — they amounted to less than $15 per capita in 2013. (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Decomposing Adjusted North Korean Merchandise Trade Exports, 2002-2013 (current $ US)

Sources: KOTRA, UN COMTRADE Database, ROK Ministry of Unification

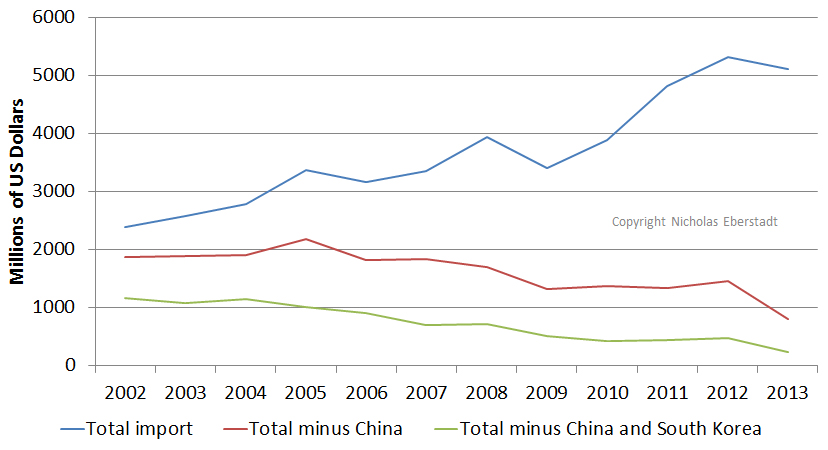

North Korea’s imports are even more unbalanced. If China is excluded, DPRK’s estimated imports tumbled, plunging from $1.9 billion in 2002 to barely $800 million in 2013. Remove South Korea as well, and North Korea’s estimated imports from the rest of the world positively nosedived, plummeting from about $1.2 billion in 2002 to barely over $200 million in 2013. (Figure 4) On a per capita basis, that would be less than $10 a year.

Figure 4. Decomposing Adjusted North Korean Merchandise Trade Imports, 2002-2013 (current $ US)

Sources: KOTRA, UN COMTRADE Database, ROK Ministry of Unification

Even for notoriously autarkic North Korea, today’s figures represent an astonishingly limited exposure to the real international commercial marketplace. Consider: during the depths of the North Korean famine of the 1990s, despite all the economic troubles attending that disaster, Pyongyang was nevertheless managing to sell and buy far more merchandise in unsubsidized markets back then than it is doing today. Remove China and South Korea from the tally, and North Korea’s estimated international trade turnover last year was at barely two-fifths its level back in 1995, nearly two decades earlier. To go by mirror statistics, North Korea today apparently has all but ceased importing commercial merchandise from the real global marketplace. Virtually all (over 95%) of North Korea’s estimated imports last year came from just two trade partners, Beijing and Seoul— two governments that still happen to support economic ties with Pyongyang for political reasons.

While such an imbalanced external trade profile can hardly count as natural, some might argue it is a consequence of coercive Western diplomacy. From this perspective, China’s growing presence in North Korean international trade accounts is an unavoidable consequence of the succession of economic sanctions that have been imposed on the DPRK by the UN Security Council (UNSC) and a growing number of international governments over the past decade. While plausible on its face, this explanation does not track with actual events in some key respects. For one thing, China’s estimated trade volume with North Korea leapt nine-fold between 2002 and 2013: thus China was not merely replacing other overseas markets for North Korea, but substantially augmenting North Korea’s total worldwide trade volume. For another, North Korea’s anemic performance in unsubsidized international markets is a long-term trend, well predating the successive UNSC sanction resolutions of the Obama era. Finally, even today only a few countries (like Canada) impose wholesale sanctions against any trade with the DPRK. Most countries instead target such things as purchases of luxury goods or military equipment, or trade with North Korean companies suspected of proliferation—if they target anything at all. International sanctions may arguably have restricted North Korean trade, but they can hardly account for the failure of North Korean commercial exports in unsubsidized world markets over the past decade, much less the simultaneous wholesale collapse of civilian merchandise purchases.

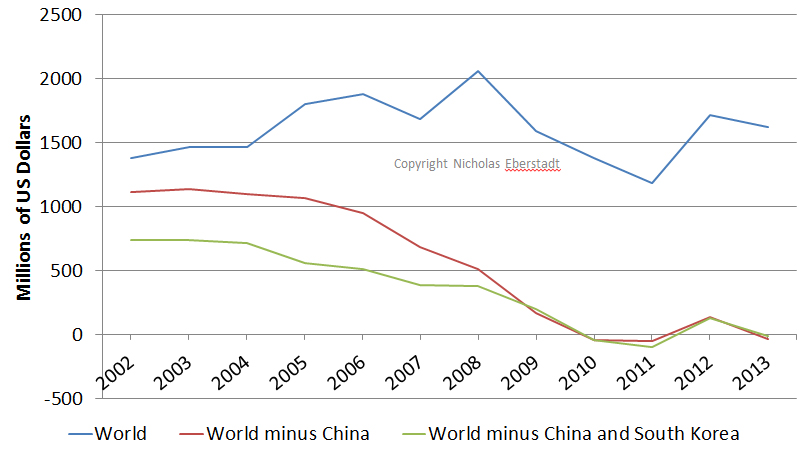

Because of its severely dysfunctional and distorted economy, North Korea requires a continuous flow of resource transfers from abroad simply to continue to function. Net commercial resource transfers into North Korea can in principle be obtained by measuring the total resource inflows entering North Korea and subtracting the outflows of resources leaving the country. One approximation of this transfer is found in the estimated balance of trade deficit, seen in Figure 5, which measures the total cost of goods being imported minus the revenue from goods being exported. From 2002 to 2013, North Korea seems to have maintained a relatively steady surfeit of imports over exports, implying that DPRK managed to induce a fairly constant annual net inflow of resources from the outside world. Over these years, North Korea’s estimated overall balance of trade for goods has typically hovered a bit above $1.5 billion annually. (Figure 5)

Figure 5. Adjusted North Korean Merchandise Trade Deficit, 2002-2013 (current $ US)

Sources: KOTRA, UN COMTRADE Database, ROK Ministry of Unification

The breakdown of that overall inflow, however, tells a different story. In 2002, China accounted for about 20 percent of the total import surfeit, and South Korea for approximately 30 percent. By 2008 however, trade deficits with South Korea had effectively ceased after the end of the country’s decade-long reconciliation experiment known as the “Sunshine Policy”. (Inter-Korean trade continues to be subsidized and politically supported by Seoul, but the scale of the resource transfers to the North has been slashed.) Back in 2008, 75 percent of North Korea’s estimated net inflow of goods from the outside world was coming from China. Since 2010, China has been responsible for basically all of North Korea’s estimated net resource transfers from its licit global trade accounts. (Figure 6)

Figure 6. Decomposing the Adjusted North Korean Merchandise Trade Deficit , 2002-2013 (current $ US)

Sources: KOTRA, UN COMTRADE Database, ROK Ministry of Unification

Thus, North Korea appears to be less willing, or perhaps less capable, of conducting regular commercial trade overseas today than it was even at the height of the Cold War. Accordingly North Korea’s economic wellbeing— it is not too much to say its very economic survival—has never before been as totally and absolutely dependent on a single foreign power as it is today on China. Indeed: the Kim Jong Un era thus far has been distinguished by its near-complete reliance on China for the net resource transfers needed to keep the juche system from collapsing under its own weight.

Pyongyang’s dyspeptic criticisms of China should alert us that North Korea’s leadership is deeply uncomfortable about their state’s dangerous new economic dependence on Beijing and is most likely preparing to reduce that dependence—in its own fashion, of course.

North Korea’s preferred methods of lessening its economic reliance on China today will likely be the same ones they have favored for garnering external resources in the past: namely, to extract aid and other economic benefits politically, from foreign governments, either through peaceable negotiations or military menace. And as in the past, the prime candidates for such “extraction diplomacy” are the other remaining “partners” from the Six Party Talks: Russia, Japan, the ROK, and the US.

As luck would have it, Russia’s aid door appears to be opening for North Korea just now: apparently as a sort of bad-will gesture towards Washington during a time of rising Russo-American frictions. Moscow has announced both the write-down of 90% of its Soviet-era North Korean debt, and the reinstitution of ruble-denominated trade arrangements for Pyongyang. But the precise magnitude of the pending windfall from the Kremlin still remains to be seen. And unless it is extraordinarily lavish, the coming Russian bequest will not in itself permit North Korea to “re-balance” China fully. So a hunt for renewed aid from Tokyo, Seoul and Washington is almost certainly in the making today.

Pyongyang’s recent overtures to resume long-dormant diplomatic discussions with Tokyo over the abductee issue suggest that unlocking Japanese aid coffers is already a high priority for the Kim Jong Un regime. After all, the DPRK has no intention of letting those abductees get home for free.

And unfortunately, the North Korean state has honed even more unpleasant means for extracting economic concessions from the US and her East Asian allies than this prospective traffic in international hostages. North Korea still extols what it calls “military first politics,” which in practice means supporting the North Korean economy through the export of strategic insecurity—sabre-rattling and nuclear brinkmanship—rather than commercial goods. Accustomed to taking extreme but carefully calculated risks to ensure its survival, North Korea may elect to ramp up an aid shakedown game that is never pleasant for its intended targets. To solve its China problem, Pyongyang may well choose to gamble on causing problems for us. We should therefore not be surprised if its state logic makes for a new phase of sharply increased (and highly orchestrated) tensions in Pyongyang’s relations with the Western world in general, and the United States in particular.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter