Since the Paris attacks of November 13, 2015, suicide bombings and/or mass shootings linked to ISIS (the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) have occurred in San Bernardino, Istanbul, Ankara, Jakarta, Brussels, Orlando, and Dhaka. Although ISIS claims responsibility for these acts of terrorism and boasts of its capability to strike beyond its borders, the attacks themselves do not appear to have been centrally commanded and controlled by the group’s top leadership.

What seems more feasible is that militant groups in Muslim countries and radicalized youth in the West are exploiting the ISIS brand by pledging their allegiance to this terrorist organization. In particular, the attacks in Europe were copycat crimes perpetrated by disaffected second- and third-generation Muslim immigrant youths who sought to co-opt the ISIS name and legitimize their criminal actions.

The collective self-radicalization of disaffected youths in cyberspace serves as a bottom-up recruitment tool for ISIS and assists in the proliferation of its independent sub-networks. Online recruitment promotes egalitarianism driven by internet anonymity and voluntarism. Through this process, the internet undermines the central control of ISIS leadership over online volunteers, even though the latter group is inspired by the former. Terror operations under such weak hierarchical control have thus become more dispersed, scattered, and unpredictable.

Democracies are more vulnerable to terrorism due to their open systems and responsibility to protect their citizens. The unfortunate implication of a “new normal” of terrorism for democracies is clear. Long-term social integration of marginalized youth will be crucial to prevent collective online radicalization, but it will take a long time and require tremendous resources. During this process, democracies will be forced to sacrifice some freedoms for security.

Differentiated Groups under the Name of ISIS

During the post-war stabilization in Iraq, the Shiite-dominated central government and the U.S. removed all public sector employees affiliated with Saddam Hussein’s Baathist Party. This massive de-Baathification, which did not take into account the compulsory party membership, caused a significant backlash from Baathists of every rank and drove many of them to cooperate with Islamic extremists.

High-profile Baathist officials, such as Izzat Ibrahim al-Douri, Saddam’s right-hand man, and Abu Muslim al-Turkmani, a former Iraqi Army general, assumed key leadership positions in ISIS, which began as an offshoot of Al Qaeda in Iraq. A fragile but tangible alliance emerged between secular Arab socialists and doctrinaire jihadists. In 2014, ISIS exploited the Syrian civil war, brought on by anti-Assad uprisings and the subsequent bloody crackdowns of the regime, and declared the Syrian city of Raqqa as the capital of its self-proclaimed caliphate.

ISIS shows no mercy to other religions and is particularly brutal to Shiites. Even Al Qaeda has distanced itself from ISIS because of the latter’s savagery and barbarity. ISIS enforces law and order based on a distorted interpretation of the Quran in its controlled territory. This pseudo-state is richer than any other terrorist organization, as ISIS smuggles out crude oil and ancient artifacts, captures hostages for ransom, and forcefully collects taxes from the occupied populace.

Bottom-up online volunteers have propelled ISIS into a multinational, multi-racial, and multilingual organization of more than 90 nationalities. The estimated number of foreign terrorist fighters was around 15,000 when ISIS’s territorial control in Iraq and Syria reached its highest point in early 2015. Since then, ISIS has appeared to expand its borders beyond Iraq and Syria and extend its influence to Europe, North America, and non-Arab Muslim countries.

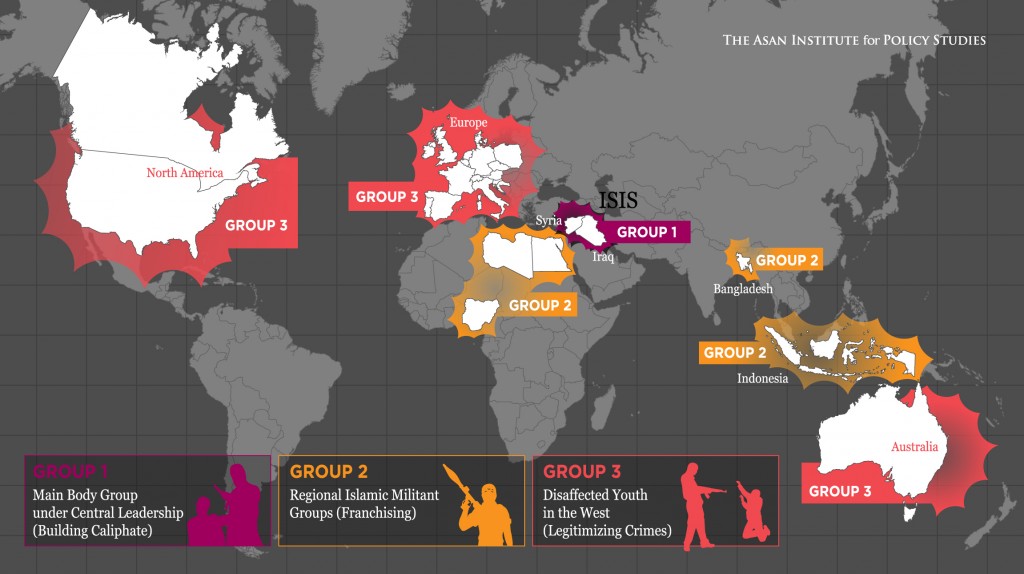

However, self-allegiance to ISIS is not tantamount to direct operational ties with the so-called caliphate. ISIS can be categorized into three distinct but connected groups. The first group is the main body of the organization under the central leadership that claims itself an ‘Islamic State’ controlling Northwestern Iraq and Eastern Syria. The second group is comprised of Islamic militant organizations based in Muslim majority countries, including Egypt, Libya, and Nigeria. The third group consists of radicalized Muslim immigrant individuals in the West, such as the Paris and Brussels terror suspects. There is little evidence of an organized chain of command between the ISIS central leadership and the latter two groups. Rather, both the second and third groups attempt to opportunistically utilize the brand name of the first group in order to gain publicity.

The second group is spread over a wide area and represents a diverse array of Islamic terrorist organizations. Ansar al-Sharia in Libya and Boko Haram in Nigeria have both declared themselves branches of ISIS. The Egyptian militant group Wilayat al-Sina, formerly Ansar Bait al-Maqdis, also swore allegiance to ISIS. This latter group claimed responsibility for bringing down the Russian passenger plane en route from Egypt to Saint Petersburg, Russia on October 31, 2015. The Pakistani Taliban and Jemaah Islamiah in Indonesia have declared their support for ISIS as well. ISIS has become a brand name for these terrorist groups, all of which were formed long before the creation of ISIS, but who now rely on its name as an effective publicity and recruitment tool.

Figure 1. Three Differentiated Groups under the Name of ISIS

The third group consists of disaffected Muslim youths in the West, particularly in Europe. The Paris attackers who murdered 130 people on November 13, 2015 were second- and third- generation Moroccan Muslim immigrants in France and Belgium. The Brussels attackers who killed 35 people on March 22, 2016 were also Moroccan descendants and had been involved in the organization of the Paris attacks. The attacks in Brussels occurred four days after the capture of Salah Abdeslam, the primary suspect in the Paris shootings.

Many of these homegrown terrorists in Europe were local gang members or petty criminals who had some experience in ISIS training camps or had tried to enter Syria. Several of the terror suspects in Paris and Brussels also had extensive criminal records for robbery and assault. Some of them had traveled to Syria, returned to Europe, and rallied Muslim immigrant youth who had been marginalized from mainstream French and Belgian societies. Abdelhamid Abaaoud, the mastermind behind the Paris attacks, is an example of the growing connection between operational field experience and lone wolf terrorist recruitment. These homebred terrorists exploited the ISIS name to make the attacks appear more demonstrative and politically meaningful but were not under the operational control of ISIS.

The U.S. cases are a bit different, given the absence of prior travel history to Syria. Omar Mateen, who committed the deadliest mass shooting in modern U.S. history, slaughtered 49 people and swore allegiance to ISIS on June 12, 2016 in Orlando, Florida. He was previously charged with domestic violence, but had not gone to Syria. A more exceptional case involved Syed Rizwan Farook and Tashfeen Malik, who carried out a horrific mass shooting in which 14 people were killed on December 2, 2015 in San Bernardino, California. The couple, who also pledged allegiance to ISIS, had no criminal record and no travel history to Syria. The long distance from the Middle East and tighter homeland security may explain the differences of the U.S. cases from those of Europe.

Weak ISIS Leadership, Weak International Anti-ISIS Coalition

The third category of differentiated ISIS groups is most alarming, given the wide range of potential terror attacks by this group. The internet has been a safe outlet for Muslim extremists to propagate their message while sheltering from the global war on terror after the 9/11 attacks. ISIS has followed this trend by posting propaganda materials online and aggressively using its Twitter account to attract recruits.

The online conversations in which followers of violent extremism around the world participate are not genuine dialogues, but only reinforce their extremist ideas. Moderates who do not agree with radical ideas opt out of the conversations or remain silent on the sidelines. Such withdrawal exacerbates a vicious cycle of self-indoctrination. Firmly self-indoctrinated and collectively radicalized youth are driven by internet egalitarianism and self-ownership and thus do not respect the hierarchical structure of ISIS. The growing autonomy of sub-networks further erodes the tenuous chain of command under ISIS top leadership.

Despite the weakened central command of ISIS, the global fight against them has reached a stalemate. This is a result of the international anti-ISIS coalition forces’ disagreement over critical issues, such as the future of Bashar Assad, support for the Kurds, and the ascendance of Iran. These differences in policy priorities have stalled progress and limited the effectiveness of the coalition.

The U.S.-led airstrikes against ISIS since August 2014 have been ineffective and uncoordinated. Most Western coalition members, including the United Kingdom, France, Australia, and Canada, have bombed ISIS hideouts in Iraq but not in Syria because the Assad regime did not make an official request for airstrikes. On the other hand, Sunni Arab coalition countries, led by Saudi Arabia, have only conducted strike operations on ISIS targets in Syria, due to the absence of an official bombing request from the Iraqi Shiite government.

When the Syrian refugee crisis came to the fore in September 2015, France and Australia began bombing ISIS targets in Syria. In hindsight, these strike operations were a game changer, as the anti-ISIS coalition campaign seemed more cooperative. Then Russia began bombing not only the Syrian rebels, but also civilians, in the name of anti-ISIS operations inside Syria.

Also, Turkey has rejected supporting the Syrian Kurds backed by the U.S., but supported the Iraqi Kurds whose aim is to bring down the Assad regime and ISIS simultaneously. The Iraqi government, on the other hand, has opposed the U.S. and the international coalition who supplied arms to the Kurdish Peshmerga in northern Iraq.

To further complicate matters, the U.S. has remained largely inactive. The Obama administration, weighed down with Afghanistan and Iraq war fatigue, has emphasized their “rebalance” to Asia and has seemed intent on staying out of the Middle East’s chaos. It has continued to deploy military advisors and a small number of special operations forces and has undertaken stopgap measures, such as precision airstrikes and small-scale special ops. While doing so, the U.S. has also pursued offshore balancing by signing a historic nuclear deal with Iran in exchange for strategic cooperation. However, this deal has caused some traditional U.S. allies in the region, including Saudi Arabia, Israel, and Turkey, to feel betrayed and dismayed by the reordering of the Middle East.

Democracy, Unpredictable Attacks, and the New Normal of Terrorism

The influence of a decentralized ISIS under weak leadership will fade away, but will not completely disappear. ISIS has lost a third of its territory and much of its revenue since early 2016. However, copycat attackers without direct affiliation with ISIS perpetrate their own acts of violence in more unpredictable ways beyond the battlefields of Iraq and Syria. Not surprisingly, ISIS claims the attackers as its own.

Democracies are easy targets for terrorists due to their open, pluralist, and responsive systems. The age of violent extremism embodied by diverse groups under the name of ISIS is upon us, and the possibility of more homegrown terror attacks persists. Thus, it has become the “new normal” for democracies to give up some liberties to fight terrorism. After the Paris and Brussels terror attacks, governments in developed countries have tightened security and restricted public freedoms. In addition to more robust security measures, social integration of disaffected youths is needed to counter violent extremism and internet radicalization.

Given that Korean society has overwhelmingly followed the route of assimilation rather than multiculturalism, the government needs to develop tolerant policies towards immigrants and minorities. Since the ISIS propaganda magazine, Dabiq, listed Korea as one of the ‘crusader’ countries, foreign workers in Korea who face abuse by exploitative employers might be triggered by online extremism. Disaffected young Koreans who call their country an inescapable ‘hell’ due to entrenched inequality, extreme competition, and high suicide rates, could also be radicalized through the internet. Although ISIS will likely devolve into a collection of scattered networks, the uncomfortable cohabitation between democracy and terrorism has already begun, even in Korea.

*The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter