▮ 2022 Assessment: Rising Possibility of Military Clash and Intensifying Competition

The international political landscape in 2022 is characterized by the rising possibility of military clashes among major powers, expansion of strategic competition among major powers across diversifying areas, intensifying conflict between the democratic and authoritarian blocs, and the efforts by major powers to further their respective spheres of influence.

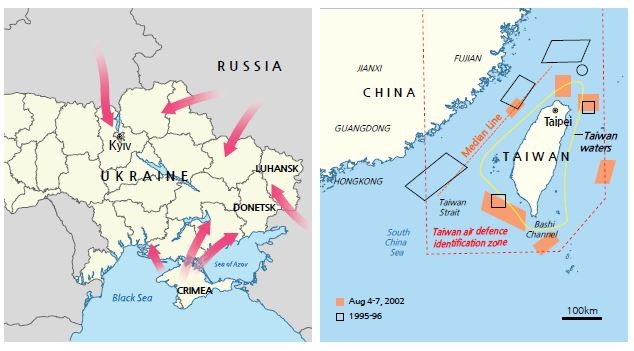

The first notable change was the aggravation of competition into conflict and the rising possibility of military conflict among major powers. Competition has always been a part of international relations and has served as the driver of both conflict and cooperation. However, competition in 2022 has continued to give place to new levels of conflict and amplified the risk of war among major powers. When the Russian invasion of Ukraine took place, it escalated into a confrontation between the United States and NATO member states against Russia, raising military tensions to a level unseen since WWII. As such, the Russian invasion of Ukraine is a leading example of a confrontation between major powers developing into significant military clashes beyond diplomatic and trade disputes and technological competition. While the United States may have failed to deter Russia from invading Ukraine, it has provided weapons and equipment to Ukraine on a massive scale in conjunction with NATO member states, fomented intense global opinion in favor of Ukraine, and took the lead in imposing sanctions against Russia. On the other hand, Russia reaffirmed its will to take over Ukraine through the annexation referenda staged in the Russia-occupied regions of Ukraine in September, thereby strengthening the base to hold the United States and NATO in check. Due to the combination of these factors, the Ukraine crisis is showing signs of becoming prolonged despite Ukraine putting up a good fight.

After Nancy Pelosi, the Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives visited Taiwan in August, China mobilized its naval and air forces to stage a large-scale armed show of force. The United States refrained from directly responding to China on the subsequent military tensions in the Taiwan Strait but conducted joint military drills with its allies and regularly performed exclusive military exercises to flaunt its naval and air powers in the South China Sea, East China Sea, and Taiwan Strait. The international community’s concerns have continued to grow as Chinese President Xi Jinping openly declared China’s stance on the non-exclusion of military options concerning Taiwan issues at the 20th Party Congress, in which Xi’s third consecutive term was officially confirmed.

While tensions in the Taiwan Strait are raising the specter of armed conflict with the advent of the U.S.-China strategic competition, the Ukraine crisis presented an even greater risk: overt threats of the use of nuclear weapons, which has been suppressed since the start of the era of nuclear armament in the 1950s. Right after Russia attacked Ukraine on February 24, Russian President Vladimir Putin insinuated the possibility of using nuclear weapons when he mentioned that “those who attempt to impede Russia’s progress will be made to pay a terrible price unprecedented in history” and ordered Russia’s nuclear forces on “special combat readiness.”1 Deputy Chairman of the Security Council Dmitry Medvedev and Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov also made threatening remarks that Russia may resort to nuclear weapons depending on the circumstances. Although Putin added that he does not wish to use nuclear weapons, Russia indeed violated an unwritten rule that a nuclear weapons state should never use or threaten to use nuclear weapons.

Along with the continually growing possibility of military confrontation among major powers, the frequency and intensity of North Korea’s armed provocations also increased and gravely threatened the peace and security of Northeast Asia. In 2022, North Korea launched at least 60 ballistic missiles in more than 30 tests; fired artillery shells, multiple rocket launchers, and cruise missiles; and conducted air exercises with its air force. This series of provocations appear to have been driven by the North’s confidence in the trilateral solidarity among the North, China, and Russia. What is noteworthy is that North Korea joined the list of nations threatening to use nuclear weapons. North Korea broke its self-imposed moratorium of April 2018 by launching ICBMs (Hwasong-15 and Hwasong-17) in March, May, and November.

Figure 1. Regions of Intensifying Military Tensions in 2022: Ukraine, Taiwan Strait

In his speech to celebrate the massive military parade marking the 90th anniversary of North Korea’s armed forces on April 25, Supreme Leader of North Korea Kim Jong Un warned that North Korea’s nuclear weapons would not be confined to deterrence but used preemptively when facing external threats to its fundamental interests. On September 8, Kim proclaimed the pre-emptive use of nuclear weapons on a massive scale like that of conventional weapons through the legislation of a new law outlining nuclear arms use. North Korea also restored the Punggye-ri Nuclear test site, which the North claimed to have demolished in 2018, and has maintained readiness for nuclear tests. This revealed that North Korea had no intention of giving up its nuclear weapons and would instead strengthen its nuclear force. The fate of Ukraine after giving up its nuclear weapons must have further driven North Korea’s nuclear obsession.

Second, the U.S.-China strategic competition began to spread to other areas and rapidly exacerbate as it developed beyond trade dispute into a struggle for global hegemony. In addition, Russia, which had been relatively sidelined amid the intensifying competition between the United States and China, emerged to take a leadership position in the realignment of the world order. Russia’s assault on Ukraine signaled the beginning of this realignment and confrontation of the values of the major powers. Through its aggression, Russia sent a warning that its existence should not be overlooked and cast light on the divide between the democratic and authoritarian blocs. The results of the voting for the resolution adopted by the Emergency Special Session of the UN General Assembly to denounce Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and demand the immediate withdrawal of Russian forces on March 2 illustrated this divide. All of the five member states (Russia, North Korea, Syria, Belarus, and Eritrea) that opposed the resolution are generally considered to be authoritarian regimes. The 32 member states that chose to abstain are also either authoritarian regimes or semi-democratic countries.2 Although it was the existing confrontational framework that deterred these countries from participating in the U.S.-led support for Ukraine, the Ukraine crisis has brought the mistrust and mutual repulsion between these opposing blocs into a sharp focus.

Figure 2. Voting Results for the Emergency Special Session of the UN General Assembly Shown on an Electronic Display at the UN Headquarters

Source: The Times of Israel

The United States proceeded with the expansion of economic cooperation networks and realignment of supply chains to hold China in check, while also providing military and economic support for Ukraine against Russia. In addition, the United States proclaimed its will to risk decoupling from its competitors, including China, in the sectors related to forward-looking technologies and cutting-edge materials through the launch of the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) in May and the preliminary meeting for the “CHIP4” alliance in September. Significantly, the IPEF launching conference coincided with the QUAD Leaders’ Summit. Although IPEF has not officially stated its intent to control or decouple from China, it is considered a de facto cooperation network for containing China along with the QUAD, and its signatories include QUAD member states and major Indo-Pacific allies of the United States. These factors indicate that IPEF will likely serve as a platform for decoupling in the future. As Russia made moves to weaponize energy such as natural gas, IPEF adjusted and realigned energy supply chains for the EU nations, implying the possibility of decoupling in the energy market as well.

Figure 3. Video Conference for the Launch of IPEF

Source: U.S. Embassy and Consulates in Australia. (Clockwise from top left on the screen) Heads of State/Government and/or Ministers of Australia, Brunei, Indonesia, South Korea, Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand, Singapore, Philippines, and New Zealand. (On the table from right) Leaders of the United States, Japan, India, and the U.S. Secretary of State.

China and Russia have not stood idle in fortifying their partnership against the United States and the West. While China did not outwardly advocate Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it opposed sanctions against Russia imposed by the United States and like-minded partners. Xi and Putin displayed their solidarity through a bilateral meeting during the annual summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation held in Uzbekistan in September. China has resented the realignment of global supply chains represented by IPEF and CHIP4 and stealthily pressured other nations to withdraw from them through bilateral and multilateral talks. Concerning Taiwan issues, China has shown more violent responses. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi poured out raw criticism of Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan, saying, “Those who play with fire on the issues of Taiwan will come to no good end.”3 China also fired artillery shells around the Taiwan Strait and launched ballistic missiles through the Taiwanese airspace as a show of its ability to use force against Taiwan.

With the complex competition among major powers affecting diverse areas from politics to economy and military, the responses of involved countries have also been varied. Israel, in spite of being one of the leading partners of the United States in the Middle East, abstained from voting for the UN’s resolution to denounce Russia concerning the Ukraine crisis. Saudi Arabia and the UAE, two major partners of the United States for security cooperation within the Gulf Cooperation Council, did not advocate for the United States as an expression of their discontent with its Middle East policies. India also remained lukewarm to the U.S. government’s attempt to draw it into QUAD as a new key partner in the Indo-Pacific region. Their responses demonstrate that the continually variable aspects of the complex competition make it even more difficult to assess gain and loss, while also implying that the U.S., China, and Russia have yet to win the confidence of such countries in their efforts to build a new world order.

▮ Traits of Complex Competition

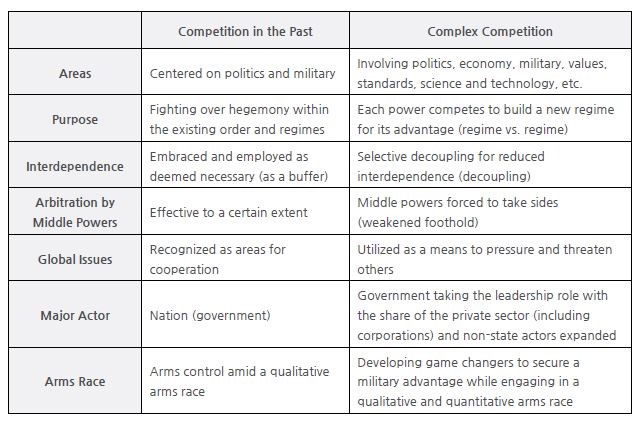

The complex competition among major powers, which became more well-defined in 2022, is distinctive in many ways. In the 2000s, the competition among major powers was aimed at expanding their influence within the world order while recognizing interdependence and striving to avoid military confrontation. However, this new dimension of all-out competition now involves diverse growth engines (economy), technology and standards, values and regimes, etc. Its physical stage has expanded to encompass not only the polar regions but also the cosmos and cyberspace.

In the past, competition focused on attaining hegemony within the existing world order and regimes. In the post-Cold War era in the 1990s, capitalist countries including the U.S., and, socialist countries including China all conformed to the regimes of nonproliferation, regionalism, etc., and agreed on the need to maintain them. G20, which was first launched around 2000 and developed into a forum for summits of its nations’ leaders in the wake of the financial crisis in 2008, is a leading example. The United States and China both attempted to enhance their prestige and reach within existing regimes in recognition of the need for coexistence. However, since the late 2010s, major powers, particularly the United States and China, have strived to initiate the realignment of the world order and regimes to their expediency. In the wake of the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, WHO’s ambiguous stance aroused controversy, and the United States and China clashed over its role. This is an example of the two countries’ competition to build a new world order. All major powers began to envision a new regime oriented toward their interests as they came to realize the shortcomings of the existing order and regimes. The United States began to envision a new order centered on state-of-the-art technologies. Its purpose is to marginalize China and its partners, instead of building a sphere of influence to coexist with the one that includes China as in the Cold War era. China also aims to rise as the leader of a new world order apart from the United States as it cannot gain full control of the existing order established by the U.S.

Global interdependence used to help avert excessive competition and extreme conflict in the past, but its significance and impact are being diluted. Globalization-induced interdependence had worked to bring nations closer together and led major powers to accept interdependent mechanisms (supply chains, etc.) and utilize them to their advantage. The acceptance of interdependence was based on the premise that overly severe competition can inflict damage on all sides involved and serve as a buffer for conflict. However, with the advent of the current complex competition, major powers appear to view interdependence as a weak link that puts them at a disadvantage. As it is impossible to completely break free from interdependence, they began to seek insulation or decoupling in game-changing sectors. This is why attempts to realign supply chains and decouple are being witnessed in sectors related to future technologies and materials such as semiconductors, batteries, and rare earth elements. Whereas economy and security were viewed as separate concepts in the past, the new concept of economic security has emerged in full force. In the past, the economic competition was no more than an instrument to increase political and military competence. However, the economy has now become weaponized as a tool for the destruction that determines a nation’s very existence and began to be considered an extension of security.

Table 1. Changing Nature of Competition

Major powers’ efforts to avert excessive conflict led to the expansion of the role of middle powers. The mechanism to arbitrate the differences of position among major powers is necessary to prevent extreme conflict. This ensured a certain latitude for middle powers. While most opted for bilateral negotiations for issues related to their vital interests, many pursued multilateral cooperation for other issues, in which middle powers played an instrumental role. However, in this new era, the standing of the middle powers is likely to be reduced considerably as evidenced by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. European arbitrators such as Germany failed to have an impact on the policies of the United States and Russia. Rather, they were forced to take sides. South Korea, Japan, and Australia in the Indo-Pacific region are facing a similar situation. Middle powers are no longer expected to arbitrate or coordinate but are put at risk of being compelled to serve as advance guards for individual blocs.

Global concerns such as climate change, pandemics, and resource depletion had functioned as the glue that held competing powers together. Now, these emerging security factors only aggravate competition and criticism. Regulations and industrial policies in pursuit of low-carbon growth are being misused by the United States and China as instruments to hold each other in check, while the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the global division due to the dispute over the virus’s origin between the United States and China.

In international relations in the 20th century, the state was the irreplaceable actor and has remained so in the early 21st century. Despite the expanded activities of international organizations and non-state actors (multinational corporations, NGOs, etc.), international relations mainly hinge on interactions among governments. The role of the state remains essential in the new era. However, the rising significance of “economic security” and cyberspace is resulting in the growth of the role of the private sector. New terrorism, ISIS, and Boko Haram demonstrated the far-reaching impact of non-state actors in international relations. The diversification of actors is adding to the complexity of relevant interactions.

From the late 20th century to the early 21st century, major powers opted for qualitative arms races instead of quantitative military build-ups. The revolution of military affairs (technological innovation of military organizations and tactics) and network-centric warfare (combat characterized by the computer networking of forces using information technology) all derive from qualitative arms races. This resulted in intensifying arms races aimed at gaining an upper hand in both qualitative and quantitative terms and the military technology war among the major powers. As such, the major powers came to focus on developing their military game changers such as hypersonic missiles, enhanced stealth and unmanned fighters, and combat robots. Reflecting on Russia’s assault on Ukraine, the major powers are highly likely to work simultaneously on the quantitative expansion of their ammunition reserves and war supplies production capacity in preparation for substantive military collisions. This new dimension of competition presents threats and risks that cannot be projected or handled by focusing on a single aspect as in the past. In this sense, this new dimension of competition can be labeled “complex competition.”

▮ 2023 Outlook: A More Dangerous and Volatile World

The traits of this complex competition are expected to be somewhat alleviated in 2023 as the major powers are projected to maintain or reinforce their policies implemented in 2022. Most of all, the risk of military conflict, which was hinted at in 2022, will grow even larger in 2023. Contrary to the forecast by some that Russia would continue to be put on the defensive as Ukraine’s troops reclaimed a substantial amount of territory, Russia can strengthen its front line at the end of 2022, deliver an attack on the Donbas again in early 2023, and arouse fears over the use of tactical nuclear weapons because, if the Ukraine War comes to a close now with Russia in shambles, Putin’s regime may face an existential calamity. Russia is likely to launch another major attack by mobilizing all accumulated military strength between December 2022 and January 2023, recapturing strategic hubs in eastern and southern Ukraine, and proposing a truce around the first anniversary of the outbreak of the war that falls on February 24, 2023. If this comes to pass, the United States and NATO member states would be forced to agonize over whether to push ahead with the war or urge Ukraine to concede. Assuredly, this projected offensive will develop into a raging battle through early 2023 as the side that rises victorious will occupy an advantageous position in the truce negotiations that could follow.

The situation in the Indo-Pacific region is even graver. China will not stand idly by as the United States moves to reinforce bilateral relations with Taiwan and raise its international prestige as such relations are considered a challenge to the One China principle. It will continue trying to bring Taiwan under its control with the start of Xi’s third term. Moreover, with Taiwan’s presidential election just a year ahead, controversy over Taiwan’s independence among different political parties can further aggravate throughout 2023. The ruling Democratic Progressive Party, which was defeated in the local elections in November 2022 due to economic problems, will employ the national independence issue again to differentiate itself from the opposition Kuomintang, and China is likely to respond to this development with the threat of using armed force. After witnessing the U.S.’s support capacity and the limitations of Russia’s weapons system through the Ukraine War, China would not entertain the possibility of attacking Taiwan. However, it may block the Taiwan Strait, fire ballistic missiles through Taiwanese airspace, and even try to occupy some parts of Taiwanese territory such as Jinmen Dao. Although the United States appears to have no intention of entering into an armed clash with China, it is likely to stage a large-scale naval and air force drill in the Taiwan Strait as a gesture to show that the democratic regime of Taiwan is under its protection. This may raise tensions in the Taiwan Strait even further.

Military tensions in the Taiwan Strait will lead to the deployment of United States military forces in the Indo-Pacific to the Taiwan region, and North Korea will view this as a weakened security commitment of the United States to South Korea and an opportunity for military provocation. North Korea, which has ramped up its nuclear threats through intensive ballistic missile testing throughout 2022, appears to believe that, unless an all-out war breaks out on the Korean Peninsula, the U.S.’s focus will shift to Taiwan if military tensions in the Taiwan Strait continue to rise and that, in such a case, it will be able to influence South Korea through nuclear threats or at least drive division within South Korea regarding its North Korea policy. North Korea is likely to consider the Taiwan Strait crisis as an opportune time for another nuclear test (if the North has not already conducted its 7th nuclear test) and ICBM test as well as carrying out conventional provocations such as the firing of artillery shells near the military demarcation line, habitual violation of the Northern Limit Line, and illegal seizure of South Korean fishing boats. If the North raises tensions on the Korean Peninsula through nuclear tests, etc., and the United States decides on the expansion of strategic assets deployment in South Korea and the reinforcement of ROK-U.S.-Japan military cooperation, China may stir military tensions near Diaoyu Islands (Senkaku Islands) and Taiwan in response. Although not likely, if North Korea is driven into a corner due to continued international sanctions, China may attempt to reinforce its leverage in negotiations by escalating tensions in the Taiwan Strait to prevent South Korea and the United States from taking control of the situation.

The United States will not change the overall framework of complex competition as the Biden administration enjoyed unexpectedly good results in the mid-term election and as the Republican and Democratic Parties are not quite at odds on issues concerning China. In a meeting with high-ranking officials of the Department of Defense in October 2022, U.S. President Joe Biden said, “The United States and China engage in stiff competition, but it should not tip over into conflict or confrontation.”4 At the U.S.-China summit held in Bali, Indonesia, in November, he mentioned that he and Xi “share a responsibility as the leaders of the United States and China to prevent competition from becoming anything ever near conflict.”5 However, the Biden administration defined China as “the only competitor with both the intent to shape the international order and the economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to do it” and as “the most comprehensive and serious challenge” to the United States in the 2022 National Defense Strategy.6 This means that the Biden administration will strive to craft diverse measures to facilitate the combination of military and non-military functions and respond to the wide spectrum of conflict, while also continuing to engage in competition with China based on “integrated deterrence” in cooperation with its allies.

Xi said at the U.S.-China summit, “China and the United States should effectively deal with our domestic affairs and join forces in pushing ahead with projects aimed at the peace and progress of humanity at the same time. China and the United States should respect each other, coexist peacefully, and cooperate for coprosperity.”7 This can be interpreted as a criticism of the U.S.’s interference in China’s internal affairs (human rights concerns in the Xinjiang Uyghur region and the Taiwan issue) while still leaving the door open for bilateral cooperation. China led by Xi in his third consecutive term will promote an even more aggressive foreign policy, and this means that the U.S.-China competition and conflict will spread to and affect all sectors and areas. China’s aggressive foreign policy will not only concentrate on U.S.-China relations but also work to pressure and coerce allies of the U.S., especially those deemed to be weaker links. This is evidenced by Xi’s emphasis on “remaining opposed to using economic cooperation as a political tool and incorporating it into the security framework” during his summit with South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol and the Five Points for bilateral relations mentioned by Wang during the South Korea-China Foreign Ministers’ meeting in August (commitment to independence and autonomy, commitment to good neighborliness and friendship, commitment to openness and win-win cooperation, commitment to equality and respect, and commitment to multilateralism). China will try to enhance solidarity within the authoritarian bloc against the democratic bloc through its reinforced partnership with Russia which is in shambles both on the domestic and international fronts due to the ramifications of the Ukraine War. For Putin, who is concerned about his political foothold being compromised due to the prolonged Ukraine crisis, cooperation with China should serve as a breakthrough. Putin is also anticipated to focus on reaching out to India, which appears to be reluctant to get involved in a confrontation between the democratic and authoritarian blocs.

North Korea’s nuclear development and continual provocations will be the center of global attention in 2023 as well. North Korea will try to use its strategic value within the authoritarian bloc to appeal to China and Russia to obtain their support to offset international sanctions, while also striving to be publicly recognized as a nuclear weapons state through additional nuclear tests, etc. It is likely to resume U.S.-North Korea negotiations to demand the full removal of sanctions. However, gaining recognition as a nuclear weapons state is no more than an attempt at a self-fulfilling prophecy of the leadership including Kim Jong Un, and is unlikely to be realized considering that the Biden administration’s goal is denuclearization. While the possibility for North Korea to opt for denuclearization in exchange for the removal of sanctions is slim, the Biden administration is also unlikely to officially recognize North Korea’s nuclear weapons as it once referred to it as a “bad deal.” North Korea’s strategic weapons that have yet to be showcased are the new submarine-launched ballistic missiles (Pukguksong-4 and Pukguksong-5), new submarines, ICBMs with reentry capability for warheads, and multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles. In 2023, North Korea will continue to demonstrate these military systems to deliver the message that its nuclear capacity is near perfection and is likely to conduct additional nuclear tests. Considering that North Korea has seriously raised tensions on the Korean Peninsula through frequently armed provocations throughout the second half of 2022, a high pace of military responses is also expected from early on in 2023.

The Middle East will continue its selective cooperation and withdrawal from engagement with major powers amid the U.S.-China decoupling and Russia’s quest to restore its global influence. In particular, cooperation with China is imperative for the oil-producing Gulf states that are overdependent on energy sources to secure new growth drivers for the future. They are discontent with the weakening security commitment of the United States in the Middle East and Near East but still have limitations in joining forces with China in terms of security. In addition, the Abraham Accords between Israel and major Middle Eastern countries, mediated by former U.S. President Donald Trump at the end of his term, remains effective. Thus, the Middle Eastern countries’ tendency to opt for pragmatic strategies to maximize their national interests, rather than taking sides with either the United States or China, is likely to continue and grow in 2023. With the energy solidarity between the United States and the Middle East weakened, the latter is highly likely to seek solutions in its favor through cooperation with China instead of maintaining the status quo.

In 2023, the ASEAN member states are likely to face comprehensive challenges related to the protective trade policies of the U.S.; reinforced economic blocs; global economic recession; and continued health, food, and energy crises in addition to variables concerning the U.S.-China competition. Southeast Asian countries, which adopted a hedging strategy to cope with the competition between the major powers, will take the approach of strengthening regional multilateral cooperation in the face of complex and wide-ranging crises. The foreign minister of Indonesia, the chair of ASEAN in 2023, condemned the major powers’ competition and proclaimed the vision of “reinforcing regional architecture.” Indonesian President Joko Widodo’s focus on external policies also supports this direction. However, it remains to be seen whether it will be sufficient to reinforce ASEAN centrality and bring the regional states back to the stage of multilateralism.

European countries (especially NATO member states) that openly opposed Russia’s aggression and tried to maintain distance from economic cooperation with China in 2022 are likely to seek an exit from the Ukraine crisis in 2023. If the United States House of Representatives, dominated by the Republican Party as a result of the midterm election, decides to reduce support for Ukraine, it may drive a subtle schism between the United States and its European allies. The Biden administration will demand more aggressive support from NATO allies to offset this reduction, and European countries are likely to revolt against this after an extended period of energy supply issues incurred by their reliance on Russian gas. Given that they chose to limit Chinese economic engagement and placed greater weight on their partnerships with the U.S., they are expected not to derail from their pro-U.S. path this time as well. However, they may take interest in growth drivers promised by the Chinese market once the Ukraine crisis is resolved. In this context, the following trends are expected to be witnessed in 2023.

1. Indo-Pacific Region Emerging as the Center of Dispute

In 2023, Russia’s capacity to continue the war will reach its limit, and Ukraine will face the fatigue of the United States and West that aspire for an exit from the war due to their prolonged support. The combination of these factors will advance the end of the Ukraine crisis. However, as indicated earlier, the risk of conflict will rise in the Indo-Pacific region. China, with Xi in his third consecutive term, will remain keen on jostling for global influence against the engagement of the United States and its allies, especially within the Indo-Pacific region. Taiwan will remain the most sensitive issue as it directly involves the One China policy.

A crisis on the Korean Peninsula is also expected. Ongoing international sanctions will add to North Korea’s economic difficulties, and another pandemic surge or the onset of a natural disaster may create a humanitarian emergency in North Korea lacking adequate healthcare infrastructure. Kim will experience difficulties in controlling North Korean society with economic trouble intensifying and threatening the livelihoods of its residents. At such times, external provocations will appear as a breakthrough. In this context, North Korea is likely to routinize nuclear and missile capability demonstrations throughout 2023. North Korea is also likely to create a larger-scale crisis to generate sentiment in the United States that sanctions are useless, while also seeking greater support from China and Russia. North Korea has already followed Putin’s lead in terms of nuclear threats in 2022 and is expected to ramp them up further in 2023.

It should be noted that elevated military tensions in the Indo-Pacific region are likely to drive tensions in other regions upward as well. For instance, if tensions in the Taiwan Strait rise and U.S. forces are focused on this region, North Korea can view this as an opportunity to take advantage of such a major-power rivalry and increase its demonstrations of military power and vice versa.

2. International Nonproliferation Regime at Stake

Nuclear threats by Putin and Kim in 2022 may further rattle the international nonproliferation regime. The prerequisite that only a limited number of nations can possess nuclear weapons and that nuclear weapons states shall respect the unwritten rule against nuclear threats and nuclear weapons use has long been nullified. Many other countries seeking nuclear capabilities will take lessons from Russia and North Korea. Iran, which is suspected of secretly providing military support for Russia in the Ukraine War, may further grow its nuclear aspirations, and this may hurt the restoration of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. As more countries are tempted to entertain the possibility of nuclear development, those countries in confrontational relations with them will have to deal with greater security risks. They are likely to shift their stance and contemplate nuclear development if they cannot be protected by the international regime or deterrence by the U.S.

Another factor that compromises the nonproliferation regime is the inability of the UN. Although North Korea continued to violate the UN Security Council’s resolution through repeated missile testing, the UN, while holding as many as ten Security Council meetings, failed to adopt a denouncing statement due to the objections of China and Russia. As this was a clear demonstration of violations of international norms being overlooked on the back of support from major powers, it compromised the very foundation of the regime. The 10th Nonproliferation Treaty review in August 2022 failed to adopt the final declaration specifying that Russia invaded Ukraine, occupied Europe’s largest Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, and incurred the risk of a radiation leak due to Russia’s objection. This incident demonstrates the limitations of the international nonproliferation regime, and this tendency will remain largely unchanged in 2023.

3. Arms Race Expected to Accelerate in Three Areas

The complex competition at the global level will entail greater demand for the military hardware required to perform effectively. As such, arms races will intensify in the three areas of conventional weapons, nuclear weapons, and military technologies in 2023. Whereas countries around the world used to concentrate on the quantitative expansion of conventional weapons in the past, they are now leaning toward securing asymmetric weapons systems to defend against a more powerful aggressor. Conventional arms races will further drive technology competition with the emergence of new warfare concepts such as multisectoral operations and intelligentized warfare. However, based on lessons learned from the Ukraine War, the world is expected to go beyond its obsession with state-of-the-art asymmetric weapons and try to expand low-tech weapons, ammunition, and military supplies in quantitative terms as well.

The world is also likely to face intensifying nuclear arms races, which is an inevitable outcome of the weakened international nonproliferation regime. Russia lowered the threshold for nuclear weapons use to a highly dangerous level in the Ukraine War. Meanwhile, China and Russia are trying to incapacitate the missile defense system of the United States by focusing on hypersonic missiles. In particular, China is steadily increasing its number of warheads. With North Korea now continually raising its stockpile of tactical nuclear weapons, the risk of nuclear weapons use is rapidly surging. The Biden administration is likely to succeed in the legacy of the Trump administration to push ahead with the modernization of the U.S. nuclear delivery system.

Technology competition is the core of future arms races, and countries are projected to ramp up their endeavors to secure military game changers. In particular, reliance on dual-use technologies is expected to rise on a continued basis. The keywords for future weapons systems are autonomy and automation, and, in this context, the focus is placed on developing autonomous weapons and the mixture of manned and unmanned platforms to operate them. At the heart of this lies AI technology and arms races. The importance of technology security is being highlighted to outpace other countries and prevent technology leakage.

4. China and Russia Reaching Out to Middle and Near East Countries

China will continue to reach out to the Middle East and Near East to extend its sphere of influence amid the ongoing decoupling. Middle Eastern countries are projected to cooperate with China’s Belt and Road Initiative in 2023 to secure more export channels for their energy resources and achieve industrial diversification. China will make continued efforts to increase its influence in the region while refraining from taking sides in regional issues (between Iran and Saudi Arabia, Israel and Palestine, etc.) based on the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, non-alliance policy, and conflict avoidance strategy. Russia will also reach out to Saudi Arabia, the UAE, etc., which are discontent with the U.S.’s security and energy market policies, while also striving to expand cooperation with Iran and Syria. Taking a step further, Russia will focus on appeasing its near-abroad countries that began to doubt the validity of their partnerships with Russia in the wake of its invasion of Ukraine and seek to expand its presence in the Indo-Pacific energy market.

5. Middle Powers Caught in a Dilemma

As the U.S.-China and U.S.-Russia decouplings proceed, other countries will be forced to agonize over taking sides. This development will be more tormenting for middle powers that have no choice but to maintain relations with both the United States and China. The United States has demanded that South Korea contribute to its steps to counter China’s moves as its ally, and China has pressured South Korea to prevent it from taking part in the anti-China push of the United States. As no specific measures for decoupling were discussed in detail in 2022, the pressures from these powers were not explicit. However, retaliatory actions can be brought into reality from 2023 not only by China but also by the United States. In the past, the United States was relatively tolerant of its allies for cooperating with China and Russia in sectors other than security as long as they remained faithful to their security commitment to the United States. As for South Korea, the United States was a security ally and China was a trade partner. However, the current complex competition defies such a simple equation. The United States may now adjust the order of priority of its allies based on their level of cooperation concerning the U.S.-led agenda items beyond security and differentiate its security commitment accordingly. In other words, “the dilemma of entrapment and abandonment,” which only applied to the security sector, can now be spread to all sectors of competition.

6. Increasing Economic Risks and Intensifying Technology Competition

The Biden administration is expected to expand the areas of decoupling from China and Russia throughout 2023. The United States is said to be preparing for diverse economic, diplomatic, military, and technological measures concerning China. In particular, additional steps for technological decoupling are projected to be put into motion with the semiconductor equipment export regulations announced in October 2022 serving as momentum. Decoupling and the realignment of supply chains incur greater costs for both the government and private sector. The problem is that it is hard to forecast such costs, and this inability inevitably poses economic risks. In 2023, the major powers are projected to take notable actions to enhance their technological prowess, which will accelerate competition in the sector of cutting-edge technologies. This raises concerns over the major powers’ attempts to monopolize technologies in semiconductors, batteries, etc., and the prevailing concept of techno-chauvinism.

7. Human Rights – New Battlefield

The value-based confrontation of the current complex competition will further intensify disputes over human rights in 2023. Once the Ukraine War nears its end, the United States is likely to raise issues with Russia’s war crimes and human rights violations in Ukraine. As the elevation of international sanctions against North Korea is difficult due to non-cooperation or obstruction by Russia and China, one of the few tools available to more powerfully sanction North Korea is human rights sanctions along with secondary boycotts. The protection of human rights also provides the grounds to limit the reach of Chinese influence in strategic competition and elicits the support of the international community. As such, the United States is expected to more aggressively target human rights violations of the authoritarian bloc in 2023, and the subsequent propaganda of China, Russia, and North Korea condemning the move as an intervention in domestic affairs will increase.

▮ Implications for South Korea

Changes in the international political landscape in 2023 will present considerable opportunities and challenges for South Korea. For the former, we can expect reinforced solidarity with like-minded countries, especially the United States. The confrontation between the blocs and decoupling in the sectors of technology and state-of-the-art materials may appear troublesome, but it can be advantageous in terms of the protection of our exclusive technologies and enhanced access to cutting-edge technologies. If we are equipped with a well-established direction to respond to issues concerning the Korean Peninsula and beyond, we will be able to increase our global contributions and national prestige. However, serious challenges lie ahead. With risk factors continually growing around the globe, the emergence of crises on the Korean Peninsula and at the regional level at the same time can overburden our security system. As evidenced by China’s economic retaliation over the deployment of THAAD and demand for the Five Points in 2022, as well as Russia’s warning of repercussions for supporting Ukraine, pressure on South Korea by some neighboring countries could be further amplified, and a joint anti-South Korea front (e.g., North Korea-China-Russia coalition) could take shape. The combination of multisectoral competition and decoupling will lead to increased risks, and, as seen through the Inflation Reduction Act of the U.S., some sectors may cause partner countries to hold one another in check. The reduced room to maneuver for middle powers can be a double-edged sword for us. If we are capable of agenda-setting, it will provide momentum for enhanced national prestige. However, we are highly likely to face competitive pressure from the major powers otherwise.

Given these possibilities, South Korea should remain alert for the following. First, it is more advantageous to take the approach of strategic clarity for regional and international issues that involve diverse values and regimes. It is impossible, let alone restrictive, to establish clear response measures for every issue. However, it is certainly more helpful to clearly define our stance on issues that reveal our identities such as liberal democracy, human rights, and the prohibition of the change of the status quo by force. Such strategic clarity may cause discord with certain countries. However, it can contribute to reinforcing transparency and expanding mutual trust in the mid-to-long term.

Second, we need to diversify our response strategies for individual issues even when we decide to participate in value-based cooperation regimes such as the democratic bloc. Sharing identical values with other countries does not necessarily mean that our national interests coincide with theirs, and thus we must be able to stand against any move that may violate our national interests. This rule should be uniformly applied to all of our actions involving IPEF and Chip 4. For example, even if we participate in an exclusive cooperation network in the semiconductor sector, we should present our blueprint for the permissible scope of intervention by other countries from production to distribution and build public consensus on it.

Third, differences of opinion and conflict with both potential partners and competitors are inevitable. As such, we must try to control the sources of conflict while maintaining cooperation. Rather than blindly preventing conflict from surfacing, we should admit and disclose the conflict to a reasonable extent and make a concerted effort to seek solutions. For example, we must stop depending on China to play a positive role in resolving the North Korean nuclear issue, etc., admit the undeniable differences in the two countries’ approaches toward North Korea, and try to find the grounds for common goals (e.g., prevention of the outbreak of war on the Korean Peninsula).

Fourth, we must reinforce cooperation with nations that share common concerns. In particular, we must take note of the dilemma that like-minded EU and ASEAN member states face and strive to seek solutions together. To this end, we should be able to propose “the South Korean way” to resolve diverse issues and try to earn their trust. This highlights the need to reinforce public diplomacy both online and offline. We must remember that existing borders are blurred in this era of complex competition and fully utilize the online space to our benefit.

Lastly, we must keep in mind that our unchanging motto for this complex competition is the wellness of the Korean Peninsula. In 2023, North Korea’s nuclear threats are likely to become increasingly explicit and further aggravate tensions on the Korean Peninsula. We must reaffirm our commitment to reinforcing South Korea-U.S. cooperation to deter North Korea’s nuclear threats from being routinized and ensure that specific measures are taken to realize such a commitment. To step up deterrence, we must take a more aggressive approach toward alternatives that were evaluated to be less feasible or only passively considered by the U.S. We must emphasize that the tactical nuke redeployment and nuclear sharing by South Korea and the United States should go beyond a political chant or diplomatic rhetoric and be pursued as a realistic option while creating consensus to push it forward.

- 1. “Ukraine invasion: Putin puts Russia’s nuclear forces on ‘special alert’,” BBC News, February 28, 2022.

- 2. This is based on ‘Democracy Index’ published by the U.K. daily, the Economist. It is hardly a perfect measure. According to the index, the U.S. is classified as a flawed democracy because it scored relatively lower in the areas of government function and political culture. The index nevertheless does not deviate much from a generally accepted view on whether a certain country is democratic or authoritarian. The Economist Intelligence Unit, Democracy Index 2021: The China Challenge (London: EIU, 2021).

- 3. “China says U.S. politicians who ‘play with fire’ on Taiwan will pay,” Reuters, August 2, 2022.

- 4. “Remarks by President Biden in Meeting with Department of Defense Leaders,” The White House, October 26, 2022.

- 5. “Remarks by President Biden and President Xi Jinping of the People’s Republic of China Before Bilateral Meeting,” The White House, November 14, 2022.

- 6. The White House, National Security Strategy (October 2022), p.8; The White House, 2022 National Defense Strategy (October 2022), p.4.

- 7. “President Xi Jinping Meets with U.S. President Joe Biden in Bali,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, November 14, 2022.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter