Introduction

The second Trump administration’s posture toward Europe has brought to the forefront a long-standing debate concerning Europe’s capacity to assume greater responsibility for its own security and defense. While the debate on Europe’s strategic autonomy had continued since the end of the Cold War, it often lacked sustained political momentum. Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 injected a sense of urgency into the discussion but substantive action was deferred until Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Central to the debate is the credibility of the United States (U.S.) security commitment to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) on the one hand, and the varying threat perceptions among European states on the other.

These developments have major implications for South Korea. The uncertainty surrounding U.S. security commitments in Europe raises questions about the future trajectory of U.S. foreign policy more broadly. To elaborate, shifts in the degree of U.S. engagement in Europe could be a temporary recalibration under the second Trump administration or it could signal the start of a path towards isolationism. Alternatively, it could reflect a reorientation of U.S. strategic focus away from Europe and towards the Indo-Pacific.

For South Korea, how the security landscape evolves in Europe will affect its own foreign policy calculations. In this context, this Asan Issue Brief analyzes the shifts in Europe’s security landscape and identifies key lessons for South Korea. The first section examines how decades of security complacency have left Europe ill-prepared to respond to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the return of the Trump administration. The second section reviews how Europe has become less cohesive in its approach to security and defense. The third section reviews the range of options available to the second Trump administration regarding the U.S. role in NATO. The final section considers the implications of these developments for South Korea and offers recommendations for South Korean policymakers.

A Europe caught off guard

Decades of security complacency have led Europe to respond poorly to two major events: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the second Trump administration. First, despite warnings from the U.S. intelligence community around November 2021 that Russia was amassing troops along the Ukrainian border in likely preparation for an incursion,1 the response from Europe was marked by skepticism and hesitation. There was widespread belief that Russia was simply demonstrating a show of force. This belief was understandable given Russia’s actions in March and April 2021, when it assembled its troops and equipment near Ukraine’s borders, citing force readiness checks.2 However, when it became clear in early 2022 that Russia was seriously considering an invasion of eastern Ukraine, Europe’s response, particularly that of France and Germany, was to work through diplomatic channels to de-escalate tensions between Moscow and Kyiv. For example, in early February 2022, French President Emmanuel Macron visited Moscow to meet with President Vladimir Putin to seek a diplomatic resolution to the tensions, to little avail.3

Likewise, Europe was unprepared for the return of the Trump administration. Transatlantic relations during the first Trump administration (2017-2021) were far from stable. It was made clear early on that President Trump viewed Europe as free-riding on the U.S. security guarantees. Subsequent actions such as withdrawing the U.S. from the Paris Climate Agreement and the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) established the unilateralist tone of the Trump administration. To this, there were some voices that questioned the reliability of the U.S. as an ally. For example, former German chancellor Angela Merkel commented after the 2017 G7 Summit that the time when Europe could depend on others was over,4 while from 2017 onwards, President Macron advocated a policy of EU’s “strategic autonomy.”5 In principle, many states in Europe did not object to the idea of increasing Europe’s independence. However, there were concerns that efforts to reduce U.S. dependence could lead to a weakened NATO6 as well as some suspicions that France was promoting its own interests over the collective EU interests.7 During the four years of the Biden administration, NATO members were reassured by President Biden’s commitment to the alliance, particularly his affirmation that Article 5—which states that an attack on one member is an attack on all—is a “sacred commitment.”8 This reassurance eased immediate concerns about U.S. disengagement, and as a result, discussions on Europe’s strategic autonomy largely remained rhetorical, without leading to concrete steps toward deeper integration or the development of independent European defense capabilities.

The impact of the peace dividend on European governance and a divided security posture

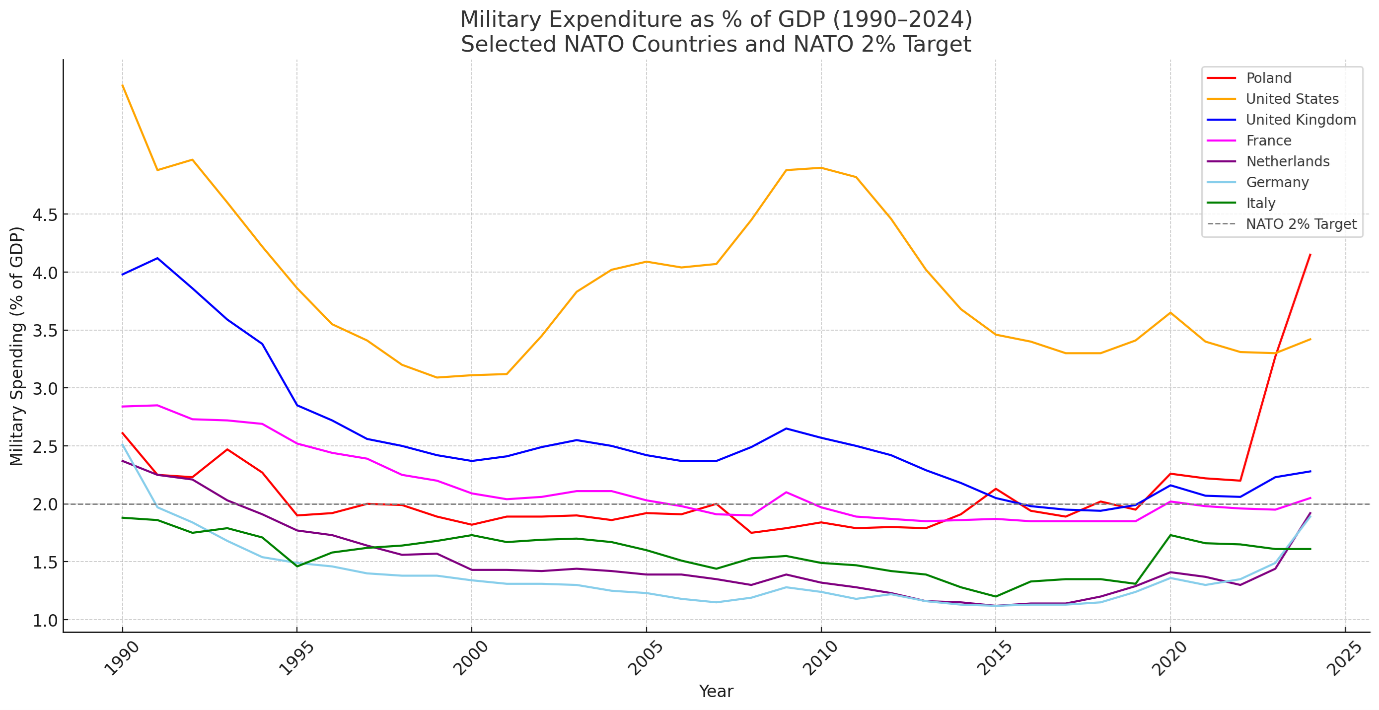

Europe’s lack of preparation for both events stemmed from a sense of complacency that had taken root in many European countries in the post-Cold War era. With the fall of the Soviet Union, countries in Europe reaped the economic benefits made possible through a dramatic decrease in defense spending. For example, Germany significantly decreased its military expenditure, dropping from 2.52% of its GDP in 1990 to 1.12% in 2015.9 The U.S. also reduced defense spending during this time but the extent was more moderate and short-term; after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, military spending in the U.S. surged once again as it launched the War on Terror.

Source: SIPRI Military Expenditure Database

This so-called peace dividend, made possible through a reduction in defense spending, had a two-fold effect on Europe as a region. First, it solidified the technocratic role of the European Union. With the threat of conventional war removed, Europe began to focus on economic, legal, and institutional integration, which were handled by technocrats and experts. To be sure, direct election of European Parliament Members (MEPs) retained the EU’s democratic character. Also, issues concerning foreign policy and defense remained at the intergovernmental level. However, the bulk of the EU’s agenda focused on managing complex policy domains, such as monetary policy and legal standardization, which were overseen by bureaucratic institutions. As a result, the EU emerged as a supranational organization largely shaped by technocratic governance. Consequently, although Europe and the U.S. have visibly expanded their cooperation on a global scale, the U.S. has increasingly become dissatisfied with Europe’s underinvestment in defense.

Second, the peace dividend created space for a broader range of perspectives regarding NATO’s role and how the alliance should respond to the second Trump administration’s disengagement from European security. For example, the start of NATO-Russia cooperation in 1994 when Russia joined NATO’s Partnership for Peace (PfP) programme raised questions about NATO’s identity in the post-Cold War era.10 Although formal cooperation was suspended after Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008 (except for a brief period of cooperation between 2010-2014 under President Dmitry Medvedev), various NATO members saw the growth of political movements that were dissatisfied with their country’s relationship with NATO. For example, both Germany’s Alternative for Germany (AfD)11 and France’s National Rally (RN)12 have advocated leaving NATO or at least restructuring their participation in NATO’s activities.

These varying threat perceptions could also be observed among NATO members. For example, some Eastern European members, such as Poland and the Baltic states, which view Russia as an existential threat, have consistently called for greater U.S. military commitment to the region. Poland, in particular, has taken steps to hedge against U.S. disengagement from NATO by significantly increasing its military spending on one hand, while also deepening bilateral relations with the Trump administration.

Other Eastern European members such as Hungary as well as Turkey have maintained close political and economic ties with Russia, further complicating NATO’s solidarity. Prime Minister Viktor Orban of Hungary has repeatedly challenged EU and NATO’s efforts to support Ukraine, such as blocking joint EU statements,13 delaying sanctions packages 14 and opposing the delivery of military aid through NATO channels.15 Turkey’s ambivalent stance has also strained its relations with NATO and the U.S. While Turkey officially denounced Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it has been slow to enforce sanctions against Moscow or reduce its economic and energy ties with Russia.16 Turkish president Erdogan’s ongoing and strategically calculated relationship with President Putin further reinforces Turkey’s efforts to be seen as a mediator between Russia and Ukraine, rather than a participant in the Western response to Russian aggression.

Meanwhile, countries such as France, Germany, and the United Kingdom (U.K.) have viewed Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine as a “wake-up call”17 and have seen Trump’s approach towards NATO as a catalyst for strengthening Europe’s security and defense capabilities. However, even here, there were some nuanced differences in how these Western states sought to respond to the situation. French President Macron proposed that France’s nuclear deterrent could serve as a “nuclear umbrella” for Europe and invited European countries to engage in a dialogue about the role of French nuclear forces in collective security18. To this, Friedrich Merz, then the expected next German Chancellor, expressed interest in discussing nuclear sharing with France and the U.K. However, he added that this should be a complement to the U.S. nuclear umbrella, rather than a replacement.19 Germany has been more cautious in tone, emphasizing the need for NATO to undergo internal reforms and enhance EU-NATO coordination, while also committing to increased defense spending. The U.K, since its departure from the EU, has framed its position as transatlantic actor, reaffirming its commitment to NATO while also emphasizing its “special relationship” with the U.S. can help keep the U.S. and Europe together.20

Divisions among NATO members over how they perceive Russia and envision the alliance’s future amid U.S. disengagement are shaped by differing threat assessments, domestic political orientations, personal relationships between leaders, and varying strategic priorities. The widening of these internal gaps has weakened NATO’s cohesion and fostered a strategic culture that is reactive rather than forward-looking in addressing potential security threats. To be sure, there have been some EU-led efforts to coordinate a region-wide defense response, such as the Readiness 2030 plan which aims to enhance joint capabilities, streamline defense procurement, and improve rapid deployment readiness. However, the question remains whether these measures have come too late, particularly in the context of the Trump administration’s declining interest in Europe’s security.

The second Trump administration’s options for NATO

The Trump administration’s disdain for Europe has already inflicted damage on the credibility of NATO. Even as a candidate to the 2016 presidential elections, Trump described NATO as “obsolete” and criticized its cost to the U.S.21 While the harsh rhetoric was diluted during his first term, Trump has consistently maintained that NATO members were not spending enough money for the region’s security. Even with the increase in many NATO members’ defense spending since 2022, Trump stated in early 2025 that the 2% benchmark should be raised to 5% of the GDP.22

Moreover, the attitudes of key members of his cabinet were clearly revealed in the leaked Signal chat where they disparaged European allies and expressed frustration over Europe’s lack of defense commitment.23 If President Trump’s approach towards NATO was largely rooted in transactional calculation, the internal exchange among his team reflects outright contempt for Europe, portraying transatlantic relations as an outdated burden rather than an asset.

In this circumstance, the Trump administration’s options for NATO include pushing for adjustments in members’ obligations, decreasing the U.S. role in the alliance, and withdrawing from the alliance altogether. There were multiple sources claiming that Trump was considering withdrawing from NATO during his first term24 as well as sources that claimed Trump intended to leave NATO if he had been re-elected in 2020.25 However, there are structures in place that would make it difficult for Trump to do so. For example, the FY2024 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) includes a provision26 that limits the president from withdrawing from NATO without Senate approval or a separate act of Congress.

In addition, it is questionable whether a formal withdrawal would be in U.S. interest. The U.S. had spent decades ensuring that its power and role in Europe could not be substituted by any European country. In the late 1990s, then-Secretary of State Madeline Albright stated that NATO’s strength is dependent on three conditions: no decoupling of European defense structures from NATO, no duplication of defense resources, and no discrimination against NATO members who are not EU members (such as Turkey, Norway, and the U.S.). This came to be referred to as the Three Ds.27 The intention was to prevent an autonomous European defense architecture that could marginalize the U.S. role in the region. While the Three Ds were not the root cause of European countries’ underinvestment in security and defense, it reinforced a structure that made Europe highly dependent on the U.S. for advanced military capabilities. Therefore, a U.S. withdrawal from NATO would undermine decades of American investment in maintaining its role as a security guarantor in the European region.

Furthermore, given that the only time in the history of NATO that Article 5 was invoked was to respond to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, the U.S. should recognize that NATO’s collective defense clause is a powerful symbol of mutual commitment across the Atlantic.

A more likely option would be for the U.S. to push NATO members to increase their defense budgets and make it conditional for participation in NATO activities. For example, Trump’s national security advisor Keith Kellogg has commented in an interview that NATO should adopt a “tiered” system of protection, where members that do not meet the 2% benchmark are excluded from protection under Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty, which states that an attack on one member is considered an attack on all.28 Other measures for members failing to meet the benchmark include excluding them from joint training and military resources.29

It is unclear how seriously these ideas are being considered by President Trump. However, Trump’s own remarks on increasing the 2% benchmark to 5% as well as commenting that he would “encourage” Russia to “do whatever the hell they want”30 indicates a clear insensitivity towards European allies’ security concerns.

Indeed, for the U.S., China – not Russia – is increasingly perceived as the top national security priority. The 2017 National Security Strategy called both China and Russia revisionist powers that want to shape a world antithetical to U.S. values and interests.31 Meanwhile, the 2022 National Defense Strategy states that China is the “only competitor with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the power to do so.”32 In the second Trump administration, the U.S. has imposed substantial tariffs on Chinese imports to pressure China economically.33 In order to shift the full weight of its resources into the Indo-Pacific region, the U.S. may seek to reduce its role in Europe. Therefore, a stronger NATO resulting from increased burden-sharing by European members would allow the U.S. to focus more on China. However, this shift could further complicate relations among NATO members, as some are keen to avoid direct confrontation with China.

Implications and Policy recommendations for South Korea

Recent developments in Europe carry significant implications. First, whether Europe is prepared or not, it is undergoing a fundamental shift in its strategic landscape. NATO’s future will hinge on several factors: the degree of U.S. disengagement, the ability of NATO members to forge a unified vision for reform, and the alliance’s capacity to overcome internal divisions over threat perception. NATO could move toward greater strategic autonomy—becoming less reliant on the U.S.—or it could keep the U.S. engaged by demonstrating a greater commitment to burden sharing. Alternatively, it could continue down a path of fragmentation. Europe’s experience with collective security serves as a cautionary tale for other regions, highlighting the dangers of complacency and overextension.

A second implication is that under the Trump administration, the U.S. is fundamentally reshaping how it views and engages with its long-standing allies. The “America First” thinking has acted as a form of shock therapy for the transatlantic alliance. In its pursuit of direct deals with adversaries like Russia, the Trump administration has shown a willingness to bypass allies. If this approach continues, Trump could, for example, seek a deal with North Korea while sidelining South Korea. This raises deeper concerns about the credibility of the U.S. security guarantees. At the same time, however, it is important not to overstate the risks. Based on President Trump’s comments on the U.S. approach towards NATO, it is clear that there is a pattern of walking back or contradicting previous statements, and not all rhetoric translates into concrete policy.

In this light, South Korea cannot afford to view the U.S.-Europe security dynamic in isolation. As a policy recommendation, South Korea’s approach to the U.S. alliance should take cues from the U.K.’s approach: remain engaged, acknowledge U.S. concerns about burden sharing, stay open to negotiations, but also clearly articulate South Korea’s own security priorities—especially in light of North Korea’s advancing nuclear capabilities. If the U.S. disengages in Europe with the intention of boosting its forces in the Indo-Pacific, this would present both opportunities and challenges for South Korea. Increased U.S. military presence could strengthen deterrence against North Korea. However, if Washington’s alliance commitments become more conditional or transactional—echoing current debates within NATO—South Korea must be prepared to adapt.

Secondly, South Korea should diversify strategic partnership, with Europe and NATO —not to hedge against the U.S., but to complement the alliance and contribute to collective burden sharing. There are several components to this: the parallels between South Korea and several European NATO members reveal shared structural vulnerabilities within the broader U.S.-led alliance system. Both regions face proximate and revisionist adversaries—North Korea in the case of South Korea, and Russia for Europe—and both remain heavily reliant on U.S. extended deterrence for their national security. This dependency exposes similar risks stemming from shifts in Washington, particularly the unpredictability associated with “Trumpism.” If Trumpism becomes a durable feature of U.S. politics, traditional alliance structures may erode, forcing allies to reconsider long-held assumptions about U.S. reliability. South Korea is well-positioned to respond to these changes by utilizing its strengths, for example, in defense technology and industry capacity. By supporting NATO’s consolidation, South Korea can play a constructive role in reinforcing global alliance structures. A more capable NATO also indirectly contributes to South Korea’s own security environment by upholding norms of deterrence and alliance solidarity in an interconnected global security order.

This interconnectedness has become even more apparent with the dispatch of North Korean soldiers to Russia and the likely transfer of Russian military technology to North Korea – events that have strategically tied the two Asia and European theatres more closely together. In this context, greater cooperation between South Korea and NATO is necessary to contribute to broader transregional stability. First, the two sides should further develop bilateral relations through the Individually Tailored Partnership Programme (ITPP). The ITPP serves as a practical framework, listing 11 sectors of cooperation, including cyber defense, space, and disinformation. Second, South Korea should identify what it can do to contribute to the post-war reconstruction process in Ukraine, such as rebuilding infrastructure and providing humanitarian support. Third, South Korea can support the growth in NATO’s relations with the IP4, or the four Indo-Pacific countries (South Korea, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand) which NATO has expanded its partnership with in the past several years.

The third recommendation is to consider how South Korea can take the lead in advancing a collective regional security framework going beyond the bilateral U.S. alliance, drawing lessons from NATO’s experience. While NATO currently faces numerous challenges, it has long served as the backbone of transatlantic security and a model of institutionalized collective defense. In contrast to Europe, the Indo-Pacific region lacks a comparable multilateral security framework. As a result, countries in the region have relied more heavily on bilateral alliances, ad hoc coalitions, and their own military capabilities to deter threats. While this may have sufficed to date, the challenges emerging from a network of authoritarian regimes demand a more coordinated regional security framework. Indeed, the Indo-Pacific region faces multifaceted threats from various sources affecting multiple domains, including North Korea’s nuclear weapons development, proliferation and China’s subversive influence and growing assertiveness around the Taiwan Strait. Ultimately, this increases the need for South Korea to pay closer attention to its expanded role within the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy, in particular, the enhanced role of the ROK-U.S. alliance, and to leverage this in its negotiations with the U.S.

To effectively respond to these challenges, South Korea needs to start a discussion with like-minded regional partners on the prospect of a collective regional security framework. In some ways, the discussion has already begun with the establishment of minilaterals, such as AUKUS, the Quad, and the NATO-IP4. While these are by no means collective security organizations, they play an important role in building trust, enhancing interoperability and signaling alignment among democracies and security partners in the region. These practices can lay the groundwork for a future security framework that is more institutionalized.

To get the discussion started, South Korea should engage with countries like the U.S., Japan, Australia, the Philippines, and possibly Indonesia to share their regional security outlook. The near-term goal could be to routinely publish a key strategic document akin to NATO’s Strategic Concept or the EU’s Strategic Compass for Security and Defence.34 The publication of such a document would lay the foundation to launch a region-wide study on the best practices afforded by NATO, in areas such as collective defense planning and interoperability. There is already some interest in Japan, as shown in an article written by then leader of Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party and now Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba, where he wrote about the need for a collective defense mechanism in Asia.35 While such proposal was met with skepticism and was shelved for the future, this shows there are some key figures in Asia who see the need for such institution. In cooperation with these groups and individuals, South Korea should start laying the groundwork so that when the circumstances are more conducive, it can play a key role in building a regional security framework.

Conclusion

The process of boosting Europe’s defense and reinventing NATO in the context of U.S. disengagement will be long and fraught with challenges. However, in retrospect, the warning signs were evident. Numerous years of U.S. rhetoric criticizing allies’ uneven burden sharing signaled a shift in U.S. commitment. Europe now faces a critical crossroads in which increased investment and a narrowing of threat perception among members could transform NATO into a more resilient alliance. Without it however, this could also mark the beginning of NATO’s decline.

These developments in Europe carry important implications for South Korea. South Korea must remain attuned to similar warning signs, and be prepared for shifts in its own regional security environment. To address the growing security challenges in the Indo-Pacific region, South Korea should take initial steps toward building a collective regional security framework. Although some may consider this premature, the increasing alignment of authoritarian regimes poses significant risks to regional stability, justifying an exploratory study to assess the appetite for a collective security arrangement. The goal would be to strengthen cooperation among the “spokes” within the hub-and-spokes alliance system, ensuring that the development of a collective regional security framework complements existing bilateral alliances, creating a mutually reinforcing mechanism. In the meantime, South Korea should also communicate closely with the U.S. to ensure that its security concerns are clearly conveyed, while reinforcing its role as a reliable ally. Finally, South Korea should expand and deepen its relations with NATO. Closer alignment would not only diversify South Korea’s foreign policy orientation and elevate its global profile, but also create opportunities for joint responses to shared transregional challenges.

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 1. Julian E. Barnes and Eric Schmitt, “U.S. Warns Allies of Possible Russian Incursion as Troops Amass Near Ukraine,” The New York Times, November 19, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/19/us/politics/russia-ukraine-biden-administration.html.

- 2. Mykola Bielieskov, “The Russian and Ukrainian Spring 2021 War Scare,” Center for Strategic & International Studies, September 21, 2021, https://www.csis.org/analysis/russian-and-ukrainian-spring-2021-war-scare.

- 3. Eliza Mackintosh, Nathan Hodge, Uliana Pavolva Dalal Mawad and Nada Bashir, “Macron meets with Putin, leading Europe’s diplomatic efforts to defuse Ukraine crisis,” February 7, 2022, https://edition.cnn.com/2022/02/07/europe/ukraine-russia-news-monday-intl/index.html.

- 4. “Merkel: Europe ‘can no longer rely on allies’ after Trump and Brexit,” CNN, May 28, 2017, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-40078183/

- 5. Sylvie Kauffmann, “Strategic autonomy is both Macron’s European DNA and his most divisive battle,” Le Monde, April 12, 2023, https://www.lemonde.fr/en/opinion/article/2023/04/12/strategic-autonomy-is-both-in-macron-s-european-dna-and-his-most-divisive-battle_6022645_23.html/.

- 6. Camille Grant, “Defending Europe with Less America,” Policy Brief, European Council on Foreign Relations, July 3, 2024, https://ecfr.eu/publication/defending-europe-with-less-america/.

- 7. Anchal Vohra, “Strategic Autonomy is a French Pipe Dream,” Foreign Policy, July 3, 2023, https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/07/03/strategic-autonomy-is-a-french-pipe-dream/.

- 8. Andrew Osborn and Steve Holland, “Biden to Meet Eastern NATO Allies in Wake of Putin’s Nuclear Warning,” Reuters, February 22, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/biden-meet-eastern-nato-allies-wake-putins-nuclear-warning-2023-02-22/.

- 9. SIPRI Military Expenditure Database. Germany’s military expenditure as a share of GDP began to slowly increase from 2016.

- 10. John Borawski, “Partnership for Peace and Beyond,” International Affairs 71, no. 2 (April 1995): 233–246, https://academic.oup.com/ia/article-abstract/71/2/233/2534588.

- 11. Dov S. Zakheim, “We don’t want a pro-Russia Germany: Why AfD is a danger to the global order,” The Hill, February 28, 2025, https://thehill.com/opinion/international/5167235-germanys-afd-presents-a-clear-and-present-danger-to-the-global-order/.

- 12. Celia Berlin, “What Would a Far-Right Victory Mean for French Foreign Policy?,” Foreign Policy, June 26, 2024, https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/06/26/france-macron-bardella-rn-far-right-victory-mean-foreign-policy/

- 13. “Orbán Vetoed EU Joint Declaration on Ukraine,” Daily News Hungary, March 22, 2024, https://dailynewshungary.com/orban-vetoed-eu-joint-declaration-on-ukraine/

- 14. Gabriela Baczynska and John Chalmers, “EU Expects to Renew Russia Sanctions after Hungarian Hold-Up,” Reuters, January 27, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/eu-expects-renew-russia-sanctions-after-hungarian-hold-up-2025-01-27/

- 15. Jean-Pierre Stroobants, “Within NATO, Hungary Has Obtained Exemption from Military Support for Ukraine,” Le Monde, June 15, 2024, https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2024/06/15/within-nato-hungary-has-obtained-exemption-from-military-support-for-ukraine_6674894_4.html.

- 16. Laura Pitel and Funja Güler, “Turkey’s Balancing Act between Russia and the West Faces a Harsh New Reality,” Financial Times, July 6, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/e7e4e73a-d536-4f91-b04c-ebe024d819e9

- 17. House of Lords International Relations and Defence Committee, Ukraine: A Wake-Up Call, 1st Report of Session 2023–24 (London: UK Parliament, 2024), https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld5901/ldselect/ldintrel/10/10.pdf.

- 18. Hugh Schofield, ‘France has a nuclear umbrella. Could its European allies fit under it?’, BBC, 7 March 2025, France has a nuclear umbrella. Could its European allies fit under it?.

- 19. Reuters. “Germany’s Merz Wants European Nuclear Weapons to Boost US Shield.” Reuters, March 9, 2025. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/germanys-merz-wants-european-nuclear-weapons-boost-us-shield-2025-03-09/.

- 20. Chas Geiger, “No Durable Peace in Ukraine if Europe Not in Talks, Says UK Minister,” BBC News, February 17, 2025, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cy9l7zn8n79o.

- 21. Nicole Gaouette and Jeremy Diamond, “Trump Rattles NATO with ‘Obsolete’ Blast,” CNN, January 16, 2017, https://edition.cnn.com/2017/01/15/politics/donald-trump-nato-europe-obsolete/index.html.

- 22. Andrew Gray and Steve Holland, “Trump Says NATO Allies Should Spend 5% of GDP on Defence,” Reuters, January 10, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/trump-says-nato-allies-should-spend-5-gdp-defence-2025-01-10/.

- 23. Financial Times. “Remarkable Sloppiness: Trump Officials’ Chat Breach Shakes Washington.” Financial Times, March 25, 2025. https://www.ft.com/content/ba6a6ef5-7b53-41a3-87ff-413812719057.

- 24. Zachary Cohen, Kevin Liptak, and Jeremy Diamond, “Trump Privately Discussed Pulling the US from NATO Multiple Times in 2018, According to New York Times Report,” CNN, January 15, 2019, https://www.cnn.com/2019/01/15/politics/trump-nato-us-withdraw/index.html.

- 25. John Wagner, “Bolton Says Trump Might Have Pulled U.S. out of NATO If He Had Been Reelected,” The Washington Post, March 4, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/03/04/bolton-says-trump-might-have-pulled-us-out-nato-if-he-had-been-reelected/.

- 26. U.S. Congress, National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024, Public Law No. 118–31, § 1250A, 137 Stat. 136 (2023), https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/2670/text. Section 1250A stipulates that: “The President may not suspend, terminate, denounce, or withdraw the United States from the North Atlantic Treaty, done at Washington, D.C., on April 4, 1949, except by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, provided that two-thirds of the Senators present concur, or pursuant to an Act of Congress.”

- 27. Madeleine K. Albright, “Press Conference at NATO Headquarters,” December 8, 1998, NATO, https://www.nato.int/docu/speech/1998/s981208x.htm.

- 28. Gram Slattery, “Trump Adviser Proposes New Tiered System for NATO Members Who Don’t Pay Up,” Reuters, February 13, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/trump-adviser-proposes-new-tiered-system-nato-members-who-dont-pay-up-2024-02-13/.

- 29. Ibid.

- 30. Andrea Shalal, “Trump Comments on Russia, NATO ‘Appalling and Unhinged,’ White House Says,” Reuters, February 11, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/us/trump-comments-russia-nato-appalling-unhinged-white-house-spokesperson-2024-02-11/.

- 31. U.S. President. National Security Strategy of the United States of America. Washington, D.C.: The White House, December 2017. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf.

- 32. Department of Defense. 2022 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America. Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2022. https://media.defense.gov/2022/Oct/27/2003103845/-1/-1/1/2022-NATIONAL-DEFENSE-STRATEGY-NPR-MDR.pdf.

- 33. Stephen Farrell et al., “Trump’s Tariffs Stoke Global Trade War as China, EU Hit Back,” Reuters, April 2, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/us/trump-escalate-global-trade-tensions-with-new-reciprocal-tariffs-us-trading-2025-04-02/.

- 34. For example, a similar report, called Regional Security Outlook, is published by the Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia Pacific (CSCAP), a Track II forum to facilitate dialogue on security matters in Asia. Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia Pacific (CSCAP). CSCAP Regional Security Outlook 2024. Singapore: CSCAP, 2024. https://www.cscap.org/publications/regional-security-outlook/.

- 34. Shigeru Ishiba, “Shigeru Ishiba on Japan’s New Security Era: The Future of Japan’s Foreign Policy,” Hudson Institute, September 10, 2024, https://www.hudson.org/politics-government/shigeru-ishiba-japans-new-security-era-future-japans-foreign-policy.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter