South Korean Youths’ Perception of China

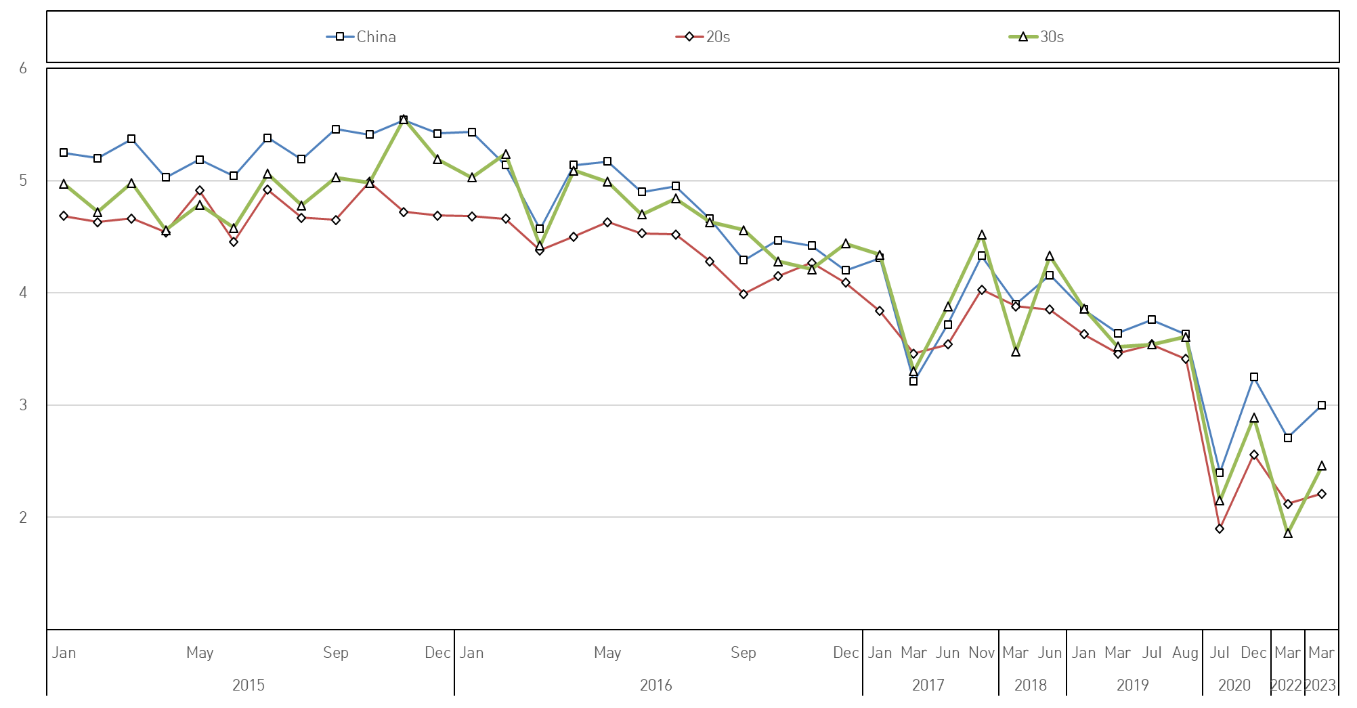

South Korean perceptions of China have deteriorated in recent years. As shown in Figure 1, based on the Asan Institute for Policy Studies favorability survey of China and its leader, the ratings dropped significantly both in early 2017 and 2020 (0=Not favorable at all, 5=Neutral, 10=Very favorable). These drops were due to China’s economic coercion against South Korea’s deployment of THAAD and the Chinese government’s hardline COVID-19 policy, which was criticized as a human rights violation in international society.

Figure 1. Favorability of China and President Xi1 (0~10)

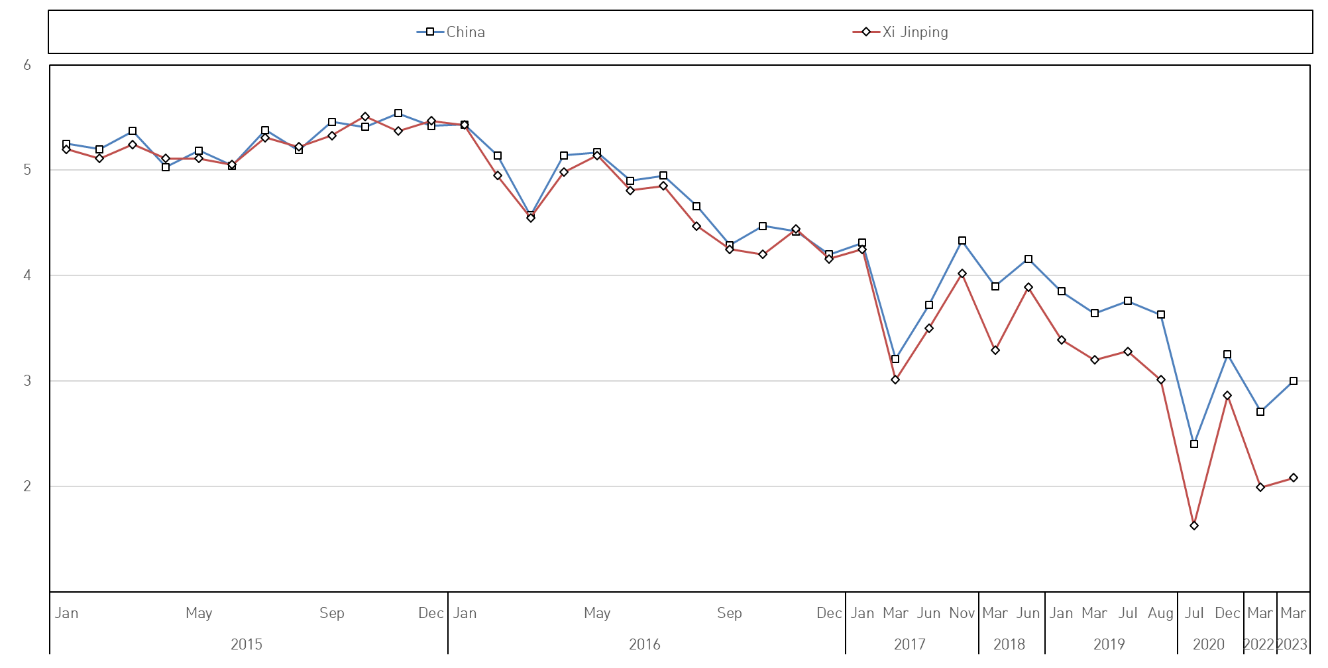

As shown in Figure 2, the favorability of China for those in their 20s and 30s has shown a more significant drop, having fallen below the average favorability rating of China since 2015. Among this age group, the favorability of those in their 20s was lower than those in their 30s. Overall, the average favorability rating of South Korean youth stayed over four points from 2015 to 2016 before suffering a massive drop in March 2017 to around three points and finally falling to around two points.

Compared to 2017, the drop in favorability ratings of South Korean youth was more significant in 2020. This means that the unfavorable views of China among South Korean youth were affected by the opacity of the Chinese authoritarian regime and the cultural conflicts that were widespread online in 2020, rather than security issues.

Figure 2. South Korean Youth’s Favorability of China (0~10)

Another survey, released by Hankook Research, also reported a negative view of China among South Korean youth. In October 2023, based on a zero to 100 point survey of neighboring countries, the score for China was only 27.8, which was lower than that of Japan (36.8) and North Korea (28.6). While the ratings of those aged over 40 stayed over 26 points (40s [26.2], 50s [32.9], 60s and over [34.2]), those in their 20s and 30s recorded a lower score for China at 15.9 and 22.2 points, respectively. Notable is that the ratings for China were much lower than those of younger age groups’ ratings of North Korea and Japan (North Korea: 20s [22.7], 30s [25.4]; Japan: 20s [40.5], 30s [34.7]).2

Factors that Affect South Korean Youths’ Worsening Perception of China

1) Anti-Korea sentiment on the Chinese internet

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the mutual exchanges between South Korea and China dramatically decreased. In that situation, anti-Korea sentiment on Chinese websites was introduced and spread to South Korea. This seems to have worsened the perception of China for the digitally savvy South Korean youth.

Internet users who display aggressive patriotism in China are called “Xiao Fen Hong (小粉紅).” They tend to identify themselves with their country and criticize those they perceive are against China or the Chinese government. Although their voices are not mainstream in China, their posts, filled with anti-Korea sentiment, were frequently reproduced and spread online. This not only caused negative effects on the Chinese perception of Korea, but also stimulated South Korean youths’ anti-China sentiment.

2) The Chinese youths’ patriotism and exclusive nationalism

Because they have received a patriotic education and witnessed their country’s rise, young generations in China have an intense patriotism. There is nothing inherently wrong with this. Still, given the long and entangled history and cultures of the two countries, this patriotism is highly likely to develop into an exclusive nationalism and superiority over neighboring states. South Korean youth, with pride in so-called “K-culture,” consider the Chinese younger generation’s exclusive nationalism as an offense and distortion of Korean culture, provoking backlash.

3) Unilateral behaviors of the Chinese authoritarian government

South Korean youths are known to consider justice and values as more important than older generations. In that sense, South Korean youths who grew up in a democratic system and are sensitive to the importance of justice believe that China’s system and its values are very different from those of South Korea. They attribute this difference to the unilateral behaviors of the Chinese government, such as intellectual property rights violations, economic coercion following the THAAD deployment, human rights issues in China, etc.

Proposals to the South Korean government

Given China’s patriotic education system and its concern about intensifying trilateral security activities among South Korea, the U.S., and Japan, cooperation between South Korea and China is unlikely to improve South Korean youths’ perception of China. Still, the South Korean government should focus on this issue and seek cooperation with China by emphasizing the future development of bilateral relations. This can ease China’s concern and help reach conciliation over the deepening ROK-US alliance and South Korea-US-Japan trilateral security cooperation while building a foundation for long-term collaboration. South Korea needs to remember that domestic anti-Japan sentiment has negatively affected South Korea-Japan relations.

First, the South Korean government needs to construct a communication channel with China to express these deep concerns. Although it is hard to expect China’s cooperation, this endeavor can send a message that South Korea is interested in developing bilateral relations and could lead to consensus building.

Second, the South Korean government should request that China manage and control anti-Korea sentiment on China’s internet by highlighting its negative impact on South Korea-China relations. Unlike South Korea, China has controlled its internet in the name of national security and social stability. In that sense, if South Korea requests China’s help for the future of bilateral relations based on Chinese laws and regulations, it can obtain some sympathy and cooperation.

Third, both countries’ governments should provide opportunities for their young generations to carry out human exchanges. In order to respond to the cultural conflicts on the internet, in addition to cultural events, the two governments need to provide exhibitions and exchanges focusing on topics relevant to young generations, such as employment, games, and marriage.

Fourth, the South Korean government should provide Chinese exchange students in South Korea with experiences that encourage them to upload South Korea-friendly videos and messages on China’s internet.

This article is an English Summary of Asan Issue Brief (2023-22).

(‘한국 청년 세대의 대중 인식 악화와 대응’, https://www.asaninst.org/?p=91034)

- 1. Asan Institute for Policy Studies (2023). South Koreans and Their Neighbors 2023. Survey Report. Seoul: Asan Institute for Policy Studies. https://en.asaninst.org/contents/south-koreans-and-their-neighbors-2023/

- 2. Hankook Research. 2023. Favorability of Neighboring Countries (Feeling thermometer). https://hrcopinion.co.kr/archives/27779

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter