On June 19, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un and Russian President Vladimir Putin signed the “DPRK-Russia Treaty on Comprehensive Strategic Partnership” (hereafter the “new DPRK-Russia treaty”) during Putin’s state visit to North Korea. This visit and the signing of the new DPRK-Russia treaty marked a significant acceleration in cooperation between the two countries since their second summit in September 2023.

Not only has the signing of the new DPRK-Russia treaty garnered international headlines, but the contents of the agreement are also unprecedented. Among others, the inclusion of language that could be seen as warranting automatic military intervention in the event of an attack on either country has raised particular concerns. Additionally, the Russian commitment to military-technical assistance, which was largely absent in the 2000 “DPRK-Russia Treaty of Friendship, Good-Neighborliness, and Cooperation,” heightens fears that Russia might help with the North Korean nuclear weapons program.

Kim Jong Un’s strategic calculus behind this treaty appears aimed at deterring possible U.S. military actions post-U.S. presidential election and strengthening North Korea’s position in negotiations with the United States. Moreover, Article 4 of the new treaty, which calls for automatic mutual military assistance in case of an armed invasion, symbolizes a return to the close relationship reminiscent of the Cold War-era 1961 “DPRK-USSR Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance.” North Korea may capitalize on this symbolic gesture to strengthen internal control and adopt a more aggressive strategy towards South Korea.

However, one should not overstate the danger as the treaty still faces challenges regarding its practical implementation. In particular, South Korea should not blindly pursue an appeasement policy with Russia solely to improve its relations with Russia, for it could be used to undermine the ROK-U.S. alliance. South Korea should realize that managing its mid- and long-term relationship with Russia is the beginning of a long haul. Additionally, it is vital that South Korea strengthen defensive measures as North Korea, emboldened by the new treaty, might conduct bolder provocations around joint ROK-U.S. military exercises in August and September.

1. Background and Context of the New DPRK-Russia Treaty

The new DPRK-Russia treaty is the product of the aligned strategic interests of both Putin and Kim Jong Un, in which showcasing close ties between their countries for the time being plays to their advantage in domestic politics and foreign policies. The rationale for Putin, having secured another six years in power in the March 2024 presidential election, is likely to expand his strategic assets regarding the invasion of Ukraine and the post-U.S. presidential election period by cooperating with North Korea. The rationale for Kim Jong Un is likely to give the impression to his domestic audience that he has secured another patron besides China in order to make up for the lack of progress in economic recovery through the reopening of the North Korea-Russia and North Korea-China borders in August 2023. Moreover, Kim Jong Un will use this DPRK-Russia cooperation as a propaganda tool to rally citizens around economic challenges and ideological fortification. Additionally, cooperation with Russia on military reconnaissance satellites could help North Korea recover from its failed satellite launch in May and showcase its nuclear capabilities.

Yet it is worth noting that Russia and North Korea showed subtle differences in their interpretation of the treaty, as Putin’s statements suggest a more cautious stance. He avoided using the term “alliance” and indicated that the treaty is not new but a revival of the 1961 treaty. His remarks imply that the content of the past treaty was simply restored at North Korea’s request.

Furthermore, it is reasonable to conclude that Putin has not abandoned relations with South Korea as Putin diplomatically set a “red line” before and after the new DPRK-Russia treaty. In a March interview with Russian media, Putin mentioned that North Korea already “has its own nuclear umbrella,” which can be interpreted as implying that Russia has no reason to provide nuclear-related technology to North Korea. Additionally, when the South Korean government expressed concern over the new treaty and hinted at re-evaluating its policy on military support to Ukraine, Putin warned that South Korea would be making “a very big mistake” if it provided lethal weapons to Ukraine. However, he later praised South Korea for not officially providing weapons to Ukraine.ow

Most importantly, the new DPRK-Russia treaty does not necessarily reflect a sharp tilt by North Korea towards Russia or abnormalities in the DPRK-China relationship. Instead, it reflects the fact that the North Korea-China relationship has not retightened as rapidly as it has with Russia. Considering the economic ties between North Korea and China, the idea that North Korea is attempting to distance itself from China lacks validity. Russia cannot replace China’s role in the North Korean economy. Furthermore, given Putin’s first visit to China in May after the March presidential election, it is likely that China and Russia have coordinated on the North Korea-Russia relationship, which diverges from Kim Jong Un’s vision of leading a North Korea-China-Russia partnership.

2. Implications by Article

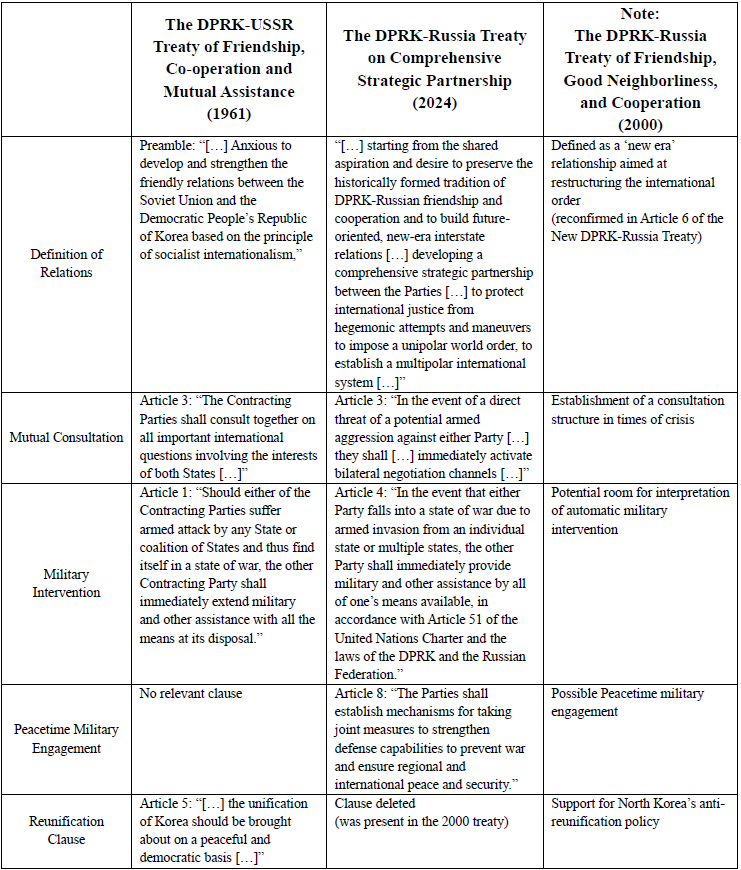

The new DPRK-Russia treaty pledges to form a closer relationship between the two countries than at any other time in history. While the preamble of the 1961 treaty defined the development of friendly relations based on the “principle of socialist internationalism,” the new DPRK-Russia treaty emphasizes “protecting international justice from hegemonic attempts and maneuvers to impose a unipolar world order.” This ultimately signifies that the DPRK-Russia relationship takes on the nature of an anti-U.S. alliance and further opposition to the ROK-U.S. alliance and ROK-U.S.-Japan cooperation.

Table 1. A Comparative Analysis of the 1961 Treaty and The New DPRK-Russia Treaty (Security Domain)

Unlike the 1961 treaty, which did not include provisions for mutual consultation in the event of a crisis, Article 3 of the new DPRK-Russia treaty states that “In the event of a direct threat of a potential armed aggression against either Party […] they shall […] immediately activate bilateral negotiation channels.” This provision aims to enhance the legitimacy of military intervention by establishing consultations at the preliminary crisis stage before any military engagement.

Regarding Article 4 of the new DPRK-Russia treaty, there are still limitations in interpreting this as a military “automatic intervention.” Currently, the most powerful alliance treaty the United States has is the North Atlantic Treaty, which founded North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Article 5 of this treaty states that, “an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all,” and it provides for assistance, including the use of force. However, in the case of NATO, the invocation of such collective self-defense rights must be immediately reported to the UN Security Council, and a state that has been attacked may lose its right to use force in self-defense if the Security Council has taken countermeasures.

In the case of the ROK-U.S. Mutual Defense Treaty, there is a clause stating, “The Parties will consult together whenever, in the opinion of either of them, the political independence or security of either of the Parties is threatened by external armed attack.” (Article 2), which led to debate over the possible interpretation of automatic intervention. However, the following factors lead to an interpretation that automatic intervention is guaranteed in the ROK-U.S. Mutual Defense Treaty: (1) the stationing of U.S. forces in South Korea; (2) military cooperation in peacetime military buildup; and (3) ROK-U.S. joint military exercises. In the case of the new DPRK-Russia treaty, terms like “without delay” and “by all means” leave room for NATO-style automatic intervention, but it does not meet the conditions such as the one in the ROK-U.S. alliance, and actual implementation remains uncertain.

Moreover, Article 8 of the new DPRK-Russia treaty states, “The Parties shall establish mechanisms for taking joint measures to strengthen defense capabilities to prevent war and ensure regional and international peace and security.” This clause was absent in the 1961 treaty. In other words, this provision, which allows for support of the other’s military capabilities even in peacetime, can apply to North Korea’s weapon support for the invasion of Ukraine and Russia’s military technology support for North Korea. Additionally, if this peacetime military support expands into regularized joint training, it can be interpreted as meeting the conditions for “automatic intervention.”

Since the U.S. consented to Ukraine using the received weapons to attack inside Russian territory, Russia could declare its “special military operation” as “war” in order to meet the conditions for the new treaty’s activation. In such a case, North Korea would have to supply even more weapons to Russia and potentially dispatch North Korean troops. Another possibility South Korea should be cautious about is that Russia may use the new treaty to justify intervention in North Korea in the event of regime instability similar to its 2022 intervention in Kazakhstan.

3. South Korea’s Responses to the New DPRK-Russia Treaty

ROK-Russia relations are likely to remain strained for the time being. Both North Korea and Russia are strongly motivated to prevent any instances of weakening or collapse of their dictatorships and to ensure the survival of friendly authoritarian regimes. Russia, therefore, will support North Korea’s “hostile two-state relationship” theory because it believes that liberal democratic unification is not favorable to its regime. From South Korea’s perspective, indirect support for Ukraine and symbolic participation in sanctions against Russia are inevitable at the moment and Russia does not see any urgent agendas for cooperation with South Korea. Therefore, as long as the deepening DPRK-Russian ties do not result in actual military transactions, attempting to contain the cooperation could weaken South Korea’s leverage over Russia. In the medium to long term, however, the South Korean government should improve ROK-Russia relations and secure Russian support for its North Korea policy and unification efforts by presenting Russia with a convincing rationale that such policies do not harm Russian interests. Such rationale should be ready for immediate use when opportunities arise.

North Korea views the new North Korea-Russia treaty as an opportunity to assert dominance in inter-Korean relations, continue to refuse dialogue and create discord in the ROK-U.S.-Japan trilateral cooperation by leveraging behind-the-scenes negotiations with Japan. Furthermore, North Korea seeks to give itself ample maneuvering room in its strategy toward the United States following the U.S. presidential election in November. Considering that North Korea’s provocations worsened around the time of the ROK-Japan-China summit in May, caution is needed around the August ROK-U.S. joint military exercises as North Korea might attempt direct provocations targeting South Korean personnel or property. Potential provocations could include: (1) shooting at South Korean reconnaissance forces in the missile danger zone (MDZ), rearming Guard Posts (GP), and conducting small-scale shootings at GP; (2) doubling down on claims of its own ‘maritime border’ and crossing the Northern Limit Line (NLL) southward in the West Sea; and (3) capturing South Korean fishing boats and attempting abductions or harm north of the ‘maritime border’ south of the NLL. To address the possibility of direct provocations by North Korea, South Korea, and the United States should deploy and strengthen strategic assets and expand the scale and level of ROK-U.S. military exercises.

Furthermore, it is important to reaffirm the strength of the ROK-U.S. alliance and ROK-U.S.-Japan security cooperation to demonstrate South Korea’s readiness. While clearly pointing out Russia’s actions that might encourage North Korean provocations, such as potential nuclear technology support to North Korea, it is sufficient to maintain a measured response that emphasizes the boundaries to be respected in ROK-Russia relations.양식의 맨 아래

There are also significant logical contradictions within the new DPRK-Russia treaty that South Korea can utilize to its advantage. For example, Russia has consistently claimed that North Korea’s “legitimate security concerns” should be considered. With the new DPRK-Russia treaty, Russia has alleviated North Korea’s concerns, so South Korea could argue that Russia should now put more effort into North Korea’s denuclearization. Additionally, since Russia signed a military cooperation treaty with North Korea in 1990 while also establishing diplomatic relations with South Korea, it cannot reasonably demand the dissolution of the ROK-U.S. alliance, even if U.S.-DPRK relations improve or normalize in the future. Given Russia’s emphasis on providing aid to North Korea in the event of an invasion, it is also crucial to document North Korea’s provocations thoroughly for better management of the Korean Peninsula situation.

As mentioned earlier, in the short term, South Korea needs to be vigilant and strengthen its readiness against the possibility of low-intensity provocations by North Korea targeting South Korean personnel or assets. This situation is expected to persist until the ROK-U.S. joint exercises in August, so it is also important to manage the mental fatigue of soldiers on the front line.

This article is an English Summary of Asan Issue Brief (2024-19).

(‘북러 밀착관계와 『북러 포괄적인 전략적 동반자관계에 관한 조약』의 함축성’, https://www.asaninst.org/?p=94902)

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter