The 2012 United States election took place in a context of major leadership transitions across Northeast Asia. China, both Koreas, Japan, and Russia as well as the United States saw changes in their top executives and in most cases in their legislatures as well. This paper examines major dimensions of the US election, highlighting certain key results likely to impact US policies in that region. It then goes on to analyze how US policy is likely to proceed toward the region generally as well as in regard to specific bilateral relationships.

Key 2012 Electoral Results

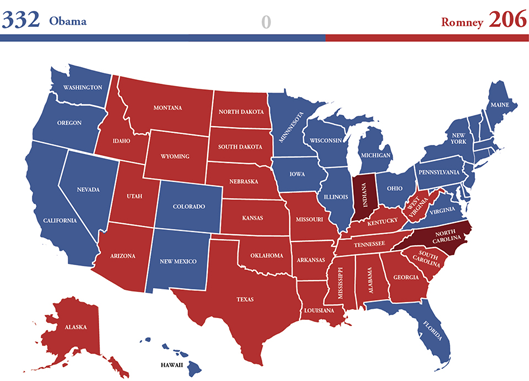

At least three major results of the US election on November 6, 2012 are likely to structure US policy toward East Asia over the next several years. First and foremost, Democratic President Obama won a rather substantial victory over his Republic opponent, Mitt Romney. During the run-up to the voting the seeming closeness of the polls and the breathless media coverage suggested a nail-biting finish. Yet, Obama’s victory was convincingly one-sided. He garnered 332 electoral votes to Romney’s 206 while besting him in the popular vote, 51.06 percent to 47.21 percent. Obama’s margin of victory represented one of the largest for an incumbent since World War II. He was also the first candidate to win 51 percent of the vote twice since Dwight Eisenhower ran-up 55 percent and 57 percent landslides in 1952 and 1956. Obama’s win was a doubly stunning achievement that defied the sluggishness of the US (and global) economy and the consistent Republican efforts that had blocked most elements of Obama’s first-term agenda.

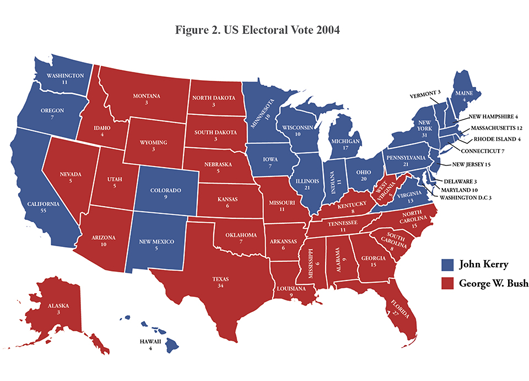

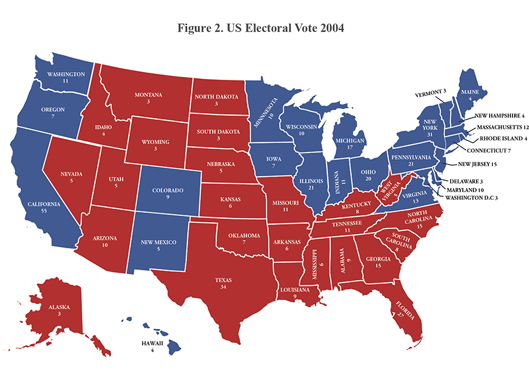

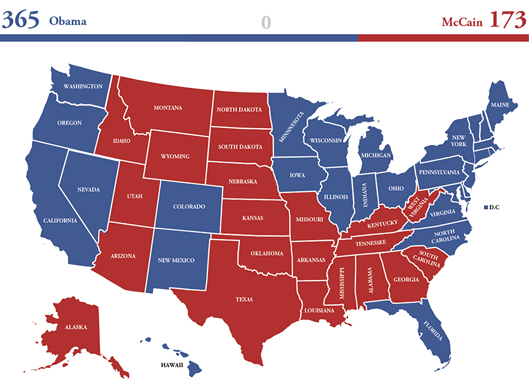

That last point highlights a second and seemingly contradictory conclusion, namely that America remains highly polarized. It is safe to say that probably 43-44 percent of Obama’s supporters and a similar percentage of Romney’s were unswervingly committed to their respective party nominees for months before the election and would, under no circumstances, have considered voting for their opponent. America’s voter polarization has a strongly regional dimension, one colorfully illuminated with the semi-permanent red-state versus blue-state division that has marked US Electoral College maps since 2000 (See Figures 1-4). Months before the actual balloting, the Electoral College map created by Nate Silver at his website showed over a 95 percent chance that Romney would win 22 of the 23 states he eventually carried while 19 states and the District of Columbia were similarly locked-in for Obama.1 At most, nine states were considered toss-ups from the early days of the campaign. America’s electoral bipolarity thus makes it unsurprising that Obama’s coattails were short: the Democrats gained only two seats of the 100 in the Senate and eight seats in the 435-member House of Representatives, leaving the Republican Party in almost absolute control of the House while the Senate remained closely divided and (due to arcane Senate rules and their recent interpretation) unlikely to provide easy passage for any Obama proposals.

At the same time, it must be noted that the limited number of seats won by the Democrats was a function largely of the rural-urban split in voting and to gerrymandered electoral districts. In fact, the 2012 election showed a strong public preference for the Democrats. As The Economist noted: “The Democrats won 50.6% of the votes for president, to 47.8% for the Republicans; 53.6% of the votes for the Senate, to 42.9% for the Republicans; and…49% of the votes for the House, to 48.2% for the Republicans…That’s not a vote for divided government. It’s a clean sweep.”2

Given its size and diversity, America’s electoral divisions are complex. But several obvious points stand out. Geographically, the Republican strongholds constitute the eleven states of the former Confederacy plus the rural states of the Midwest.

The Democrats in turn have been strongest in the more densely populated coastal states of the West and the Northeast and the industrial Midwest. Despite the generally anti-big-government ideology of their populations, the red states that are disproportionate beneficiaries of government programs receiving US$1.46 in federal tax monies for every tax dollar sent to Washington while it is the predominantly Democratic states that pay the higher tax bills.3

At the individual level, several broad categorizations are possible. Romney voters tended to be whiter (59% of whites voted for Romney versus 39% for Obama); older (55% of those over 65 vs. 44% for Obama); richer (only 38% of those making less than $50,000 per year voted for Romney while 64% supported Obama); more rural (Romney 59% vs. Obama 37%); and more male (52% of men voted for Romney vs. only 45% of women; 55% of women supported Obama). Obama gained his greatest margins from the young, women, blacks, Hispanics, Asian-Americans, and metropolitan residents. And in something of an oddity, while Obama drew heavily from those without high school degrees (64% vs. 35%) and slightly more college graduates voted for Romney (51% vs. 47%), Obama did better among Americans with post-graduate degrees (55% vs. 42%).

Such demographic divisions are reinforced by the insulated parallel universes experienced by Republican and Democratic supporters. Fox News viewers lean heavily ‘red’ while MSNBC viewers and the New York Times readers shade heavily ‘blue.’ Republican candidates have strong support from among evangelical Christians and conservative Catholics while non-church goers and Jews voted overwhelmingly for Obama. Neighborhood housing patterns add to America’s bifurcation with most Americans self-selecting to live near those whose beliefs resonate with and reinforce their own.

Yet it is not clear that such voter level divisions will exert much direct influence over traditional components of American foreign policy toward East Asia. This is because of a third point about the election, namely the limited degree to which foreign policy issues were salient to the campaign, in striking contrast to presidential and congressional elections between 2004 and 2008 elections when the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan heavily shaped the electoral outcomes. Exit polls for 2012 revealed that only five percent of voters tapped foreign policy issues as their highest concern. Instead, 59 percent of the voting population identified the economy as their major concern while an additional 15 percent said the federal deficit and government spending were their key anxiety. Such numbers suggest that elected politicians will be relatively free from constituent pressure to behave in particular ways as they pursue foreign policy.

American Policies toward East Asia

How will the electoral results shape American policy toward East Asia? Most clearly, with foreign policy playing at best a minimal role in the campaign and with Obama’s strong victory, one should expect large dollops of continuity in the basic strategy pursued over the remaining four years of the Obama administration.

Unlike a new administration, particularly one that involves a change in the party of the president, the United States will be free from the nettlesome six to nine month period devoted to staffing the 2,000-3,000 key government policy positions. Nor will the Obama administration be engaging in extensive reviews of policies pursued by prior administrations. It should be primed to continue the main lines of existing policy.

Nevertheless, several top policymakers linked to East Asia have left or will be leaving, most prominently, Hillary Clinton and Kurt Campbell at State, John Panetta at Defense, Jeff Bader at the National Security Council, and probably Tim Geitner at Treasury, to mention only the most conspicuous changes. Individuality can affect tactics and effectiveness so the impact of these changes should not be ignored. Yet, the administration has a relatively deep bench from which to draw replacements.4 Moreover, the overall direction of the administration’s policies is likely to continue, even as new individuals might exert personally different influences at the margins.

At the core of the Obama administration’s strategy has been the “repositioning” or “pivot” toward Asia. Seeking to reverse the heavy commitment of US funds, troops and leadership attention devoted to the Middle East and Afghanistan by the Bush administration, Obama’s government has ended the military commitment in Iraq and is scheduled to extract all combat troops from Afghanistan by 2014. One of the more clearly articulated statements of the administration’s commitment to devote enhanced US attention to East Asia came in Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s November 2011 Foreign Policy article, “America’s Pacific Century.” As she put it, “[o]ne of the most important tasks of American statecraft over the next decade will…be to lock in a substantially increased investment—diplomatic, economic, strategic, and otherwise—in the Asia-Pacific region…[b]ecause the Asia-Pacific region has become a key driver of global politics.” 5

Media attention to “the pivot” has stressed the US alliance structure along with plans to reposition additional naval forces in East Asia leading to facile conclusions that future American policy will be largely about “containing China.” It is imperative to underscore the fact that while bilateral alliances remain a core component of US policies and that many American policymakers indeed fret about the rapid modernization of Chinese military power and that government’s recent assertiveness on a host of previously quiescent issues, the pivot is far more nuanced and multidimensional than a simple bolstering of military force in the region.

As Clinton put it, the emphasis will be on “…six key lines of action: strengthening bilateral security alliances; deepening our working relationships with emerging powers, including with China; engaging with regional multilateral institutions; expanding trade and investment; forging a broad-based military presence; and advancing democracy and human rights.”6

The multipronged nature of American involvement is manifested among other things in both Clinton’s and Obama’s frequent visits to Asia; in the US decision to sign the ASEAN Treaty of Amity and Cooperation; the appointment of a US ambassador to ASEAN; the behind-the-scenes efforts to encourage regime change in Myanmar; American entry into the East Asia Summit and its reinvigorated participation in the ASEAN Regional Forum and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum; multilateral cooperation in police, disaster relief, and counter-terrorism efforts; and in the vigorous pursuit of outgoing investments to the region and the more explicit embrace of geo-economics as a strategy within the region. The latter would include the bilateral Strategic and Economic Dialogue with China, the Korea-US free trade pact (KORUS), and the vigorous pursuit of a Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement.

At the same time, because the American public and the two parties remain deeply divided over economic issues geo-economics may be difficult to pursue. Given the rising disparity between US taxes and US spending and the consequent ballooning of public debt and debt servicing payments, and given the fact that the Republicans have the capability to block most tax hikes and most economic stimulus packages while Democrats are unlikely to allow serious cuts to social programs, the US economy will likely continue to struggle unless some surprising “grand bargain” is reached on US fiscal and social welfare programs. The failure to find such agreement, the highly contentious political battles over taxes at the end of 2012, and the promise of more economic battles to come during February-March 2012 over the debt ceiling and government spending, all suggest that America’s policymakers will find it difficult to give serious consideration to any other issues for some time. It also suggests that American economic recovery will be hard to achieve if such a confrontational political kabuki continues. The result will be that US policymakers will be impeded from relying heavily on what was once a key tool of American foreign policy, namely national economic and financial muscle, to shape events globally and regionally. Economic disagreements domestically will remove a key tool from America’s foreign policy tool kit.

How is this general framework for America’s Asia policy likely to develop toward key countries in Northeast Asia? Clearly future policies will be the outcome of an interactive process; what the United States does (and can do) will depend heavily on what other countries do and vice versa. Furthermore and even more inimical to the most well constructed strategies will be unexpected developments. As former British Prime Minister McMillan is alleged to have responded when asked what would be the biggest impediments to fulfilling his plans, “Events, my dear boy, events.” With such caveats in mind and now that the leadership transitions in China, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK or North Korea), the Republic of Korea (ROK or South Korea), Japan, and Russia have all been completed, it is possible to make some preliminary observations about probable bilateral relations within the broader context of America’s regional policies.

China

The most important relationship for the United States in Northeast Asia has been shifting from US-Japan to US-China. Bilateral China-US relations appeared to be on a smooth and positive trajectory for most of the 2000s as marked, for example, by US assistance for China’s accession to the World Trade Organization, the growing financial and trade interdependency between the two, and cooperation in dealing with North Korea’s nuclear program through the Six-Party Talks. Things have since become more problematic.

As was noted above, many analysts, including a considerable number in China, have interpreted “the pivot” as explicitly targeted at stymieing China’s growth, development, and influence in the region. Without a doubt, the pivot seeks to hedge against Chinese actions that might conflict with those of the United States. However, the Obama administration’s policies toward China involve far more than classic notions of “containment” might convey. A vigorous combination of engagement and hedging continue to drive US policies with the emphasis on sustained engagement, particularly on financial and economic matters, diplomatic cooperation in and outside of the East Asian region, and strong support for China’s inclusion in global and regional multilateral institutions.

At the same time, China has been far more assertive in its regional actions, particularly since the Lehman shock and the subsequent meltdown of the US and European economies, which convinced many in China that America’s hegemony was in decline. Following a decade of successful efforts by Chinese leaders to avoid confrontation and enhance regional trust, China seemed to shift gears with, among other things, enhanced support for DPRK military actions, including the sinking of the Cheonan and the shelling of Yeonpyeong Island in 2010; rapid retaliation against countries that entertained the Dalai Lama; first-time threats to impose sanctions on US manufacturers who sold weapons to Taiwan; a new assertiveness on vastly expanded maritime claims in the East and South China Seas; interference with the operations of oil exploration vessels in waters claimed by the Philippines and Vietnam; the launching of China’s first aircraft carrier; refusal to participate in IMF meetings in Tokyo; and turning a blind eye toward violent anti-Japanese demonstrations over the islands called Senkaku by Japan and Diaoyu by China.

It is difficult to determine how much this new assertiveness is the result of a strategic shift by the Chinese leadership and how much is the outgrowth of quite specific events and the desire to present a tough posture in the face of its own leadership transition. But the US combination of engagement and hedging is designed to provide the United States with the sticks to push back against potentially threatening behavior by China while at the same time holding out the carrots that might encourage less aggressive and problematic behavior. Most surely the greatest difficulty for both countries will be to avoid acting in ways that trigger the classic strategic dilemma in which each side, though seeking to avoid confrontation, is convinced that actions by the other party are offensive and must consequently be met by equal if not greater confrontation. The early post-election interactions of Xi Jinping and Barack Obama could well be critical in setting the tone for the next several years of US-China interactions.

Furthermore, while the two cooperate well in some non-regional matters such as anti-piracy activities off the Somali coast, they have differed strongly on policies toward Iran and Syria for example, and they have quite conflicting views of how to deal with global warming. To the extent that they can find common ground on non-regional issues, there may be positive spill-over effects within the region; but conversely lack of cooperation elsewhere heightens the stakes and the mistrust within Asia.

North Korea

North Korea is likely to provide its irregular but persistent neuralgia to US regional policy efforts. The intense secrecy of the regime makes confident predictions difficult but as of the end of 2012, the regime appears to be successfully transferring power to the third Kim and he in turn appears to be reducing the previous dominance of the military in favor of greater party influence. And with Jang Sung-taek taking on a preeminent role behind the scenes in doing so, economic reforms appear to be advancing if only incrementally. Yet military prowess and confrontation remain hallmarks of DPRK “diplomacy.”

Further, US efforts to engage more closely with the regime were shattered by North Korea’s attempted launch of an ICBM (or satellite) within weeks of the so-called Leap Day agreement that appeared to soften US-DPRK relations and later by its successful launch in early December 2012. The Obama administration is thus likely to continue its longstanding policy of “strategic patience,” endeavoring to keep a watchful eye open for any openings provided by the North but with an increased reluctance to allow North Korea to regain its position as the focal point of US diplomatic efforts in the region that it enjoyed in the early years of the Bush administration.

South Korea

If relations between the United States and China and the United States and North Korea are likely to be bumpy, relations between the United States and South Korea provide a striking contrast. Today links between the two constitute perhaps the single best bilateral relationship the United States enjoys in Northeast Asia. Obama and outgoing president Lee Myung-bak benefitted from a surprisingly close personal relationship. Whether or not Park Geun-hye can recreate such a close personal relationship, she was undoubtedly a more welcome victor than her opponent Moon Jae-in, whose policies might have provided far less continuity than Park’s. That continuity is marked by a number of positives to which she and her party will fall heir and are likely to embrace: the benefits of a close economic relationship sealed by the real and symbolic power of the KORUS agreement; the rebasing arrangements for US troops; the expanded missile range accorded to the ROK military; and the agreed transfer of wartime operational control to ROK forces; among other things. Furthermore, both countries are in large accord on their goals and strategies toward North Korea and the denuclearization of the peninsula. Various bilateral irritants are certain to arise but these are likely to be relatively easy to resolve given the ongoing strengths of the ROK economy, ROK-US accord on most matters of alliance strategy, and demonstrated ROK willingness to play a larger regional role. If one is to search for potential trouble spots in the US-ROK bilateral relationship the most plausible division is likely to come from the further souring of the ROK-Japan relationship. The United States, which counts Japan and South Korea as its two closest bilateral allies in the region, would obviously prefer similarly close relations between Japan and South Korea. Yet a host of potential bilateral sore spots suggest that the future will be rocky: historical memories of Japanese colonialism and sexual slavery; the recent escalation of countervailing claims over Dokdo (called Takeshima in Japan); the prime ministership of Abe Shinzo, with his strongly embedded nationalism; the high degrees of competition among a number of ROK and Japanese companies in areas such as autos and consumer electronics; and the unfailing reality that Japan’s economy and society have become more introspective over the last two decades while South Korea’s have moved toward more openness and global interaction. All of these bode poorly for easy ROK-Japanese cooperation.

Japan

Despite Japan’s economic troubles, the US-Japan relationship remains quite strong, particularly in the diplomatic and military arenas. On a host of global issues the two countries walk in cooperative step with one another. Indeed, in the military arena, particularly since the Bush-Koizumi years, the two countries have expanded their cooperation on a wide range of items including missile defense, amphibious capabilities, force transformation and projection, intelligence gathering, cyberspace, and improved command and control, to mention but a few.7 The most significant area of bilateral conflict in the military arena continues to be the proposed relocation of the US Marine base at Futenma, an issue which has seethed on a slow boil for over a decade.

It is on other areas, most particularly economic matters, that the two countries have faced greater difficulties. In essence, US policymakers have grown ever more dismayed by the revolving door of Japanese leaders, the “twisted Diets” and entrenched interest groups that prevent the government from dealing with (or indeed reverse prior efforts designed to deal with) deregulation, high levels of public debt, and a domestic economy that is among the most highly resistant to internationalization of any OECD country. To America’s frustration, Japanese leaders and the Japanese public appear to have turned inward over the last two decades and have resisted working cooperatively with the United States on regional and global issues that transcend the explicit arenas that define bilateralism.

Conclusion

This essay has examined the US election of 2012 and the implication of that election for American policies toward East Asia. The key arguments have been that the Obama administration won a strong victory and is likely to continue most of its prior policies toward Asia, most notably following through with its repositioning, or pivoting, toward the most economically dynamic region of the world. That pivot, it was argued, is meant to be multi-dimensional and not simply military in its engagement with the region.

At the same time, given the sharply bifurcated character of the US public along with the two major parties, the Obama administration is likely to find itself handicapped by Republican opposition on a number of issues. Of special concern will be the difficulty of reaching bipartisan accommodation in dealing with the rising costs of America’s social safety net in a climate not likely to yield enhanced tax revenues or program cuts.

Within Northeast Asia, the United States must seek to manage an increasingly complex relationship with China and periodic outbursts from North Korea. At the same time, its bilateral relationships with Japan and South Korea are largely solid and will provide the United States with intra-regional support as it tries to deal with China and North Korea. Without question, one of the Obama administration’s bigger challenges may well be trying to calm the rising tensions not only with America’s potential competitors and adversaries but also with its two major allies. Whether nationalism continues to drive policies more than regional cooperation remains one of the more puzzling uncertainties of the region and the answer to that may well determine a great deal of America’s success in implementing its policy goals in East Asia.

Figure 1. US Electoral Vote 2000

Figure 2. US Electoral Vote 2004

Figure 3. US Electoral Vote 2008

Figure 4. US Electoral Vote 2012

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

-

1

Nate Silver, “Five Thirty Eight: Nate Silver’s Political Calculus,” http://fivethirtyeight.blogs.nytimes.com.

-

2

“Congressional Representation: Now that’s what I Call Voter Suppression,” The Economist, November 15, 2012.

-

3

Dave Gilson, “Most Red States Take More Money from Washington than they Put In,” Mother Jones, February 16, 2012, http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2011/11/states-federal-taxes-spending-charts-maps. See also: Dean Lacey, “Blame FDR and LBJ for ‘Moocher’ Paradox in Red States,” Bloomberg News, September 19, 2012, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-09-19/blame-fdr-and-lbj-for-moocher-paradox-in-red-states.html.

-

4

E.g., see: “The Nelson Report,” Samuels International Associates, Inc., November 7, 2012, (privately subscribed report); for information contact Samuels International Associates Inc., https://www.google.com/search?q=The+Nelson+Report&ie=utf-8&oe=utf-8&aq=t&rls=org.mozilla:en-US:official&client=firefox-a.

-

5

Hillary Clinton, “America’s Pacific Century,” Foreign Policy, November 2011, http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2011/10/11/americas_pacific_century.

-

6

Ibid.

-

7

For details, see: T.J. Pempel, “Japan: Divided Government, Diminished Resources,’ in Strategic Asia, 2008-09: Challenges and Choices, ed. Ashley J. Tellis, Mercy Kuo, and Andrew Marble (Seattle: National Bureau of Asian Research, 2008), 106-133; and T.J. Pempel, “Japan’s Search for the ‘Sweet Spot’: International Cooperation and Regional Security in Northeast Asia,” Orbis 55, no. 2 (Spring, 2011): 255-273.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter