THE KOREAN DEFENSE REFORM 307 PLAN by Bruce W. Bennett, The RAND Corporation1

The Republic of Korea (ROK) Ministry of National Defense (MND) has regularly prepared mid- to long-term military modernization plans. These plans provide helpful targets for the development of the ROK military, which has consistently striven to become more self-reliant. ROK military capabilities are critical given the military threats posed by North Korea, ranging from provocations to major attacks that include the potential use of nuclear weapons.

The ROK MND introduced a new modernization plan on March 8, 2011. This plan is referred to as the Defense Reform 307 Plan, reflecting the approval of the plan by ROK President Lee Myung-bak on March 7 (3/07). A major thrust of this plan is countering the North Korean military provocations that were particularly serious in 2010. But the plan is also broader, covering a number of other key issues. Thus far, open reports of the plan have been limited, and it appears that elements of the plan are still being developed. Nevertheless, the available information suggests that this plan will provide helpful improvements in ROK military capabilities. Still, several key provisions of the Defense Reform 307 Plan either have not been developed yet or have not been released, raising some important questions on the future of the ROK military.

DRP 2020: ADDRESSING ROK DEMOGRAPHICS

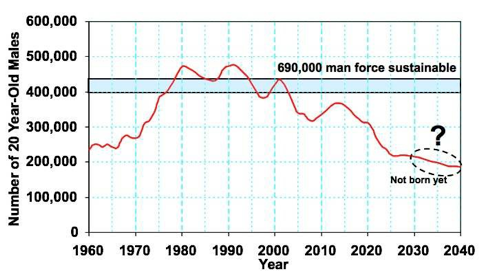

The previous ROK military modernization plan was referred to as the Defense Reform Plan (DRP) 2020. Initially introduced in the fall of 2005, this plan established targets for ROK force development through the year 2020. Its focus was on ROK demographic changes that would affect the manpower available to the military, as illustrated in Figure 1. From 1977 through about 2002, 400,000 or so young men turned draft age almost every year, enough to sustain a ROK military of 690,000 or so personnel (the significant majority of whom were draftees). By 2020, that number would be just over 300,000, and by 2025 the number would be only about 220,000. Because almost all draft age men are brought into the military either as volunteers or as draftees, this reduction in available manpower means that the ROK military manpower will grow smaller in coming years. In addition, former President Roh Moo-hyun set in motion reductions to the draft service period from 26 months for the Army to 18 months (by 2014) that would further reduce the number

Figure 1 : The ROK Military’s Demographic Problem

In order to sustain ROK military capabilities, DRP 2020 was designed to enhance military equipment in a classical manpower versus technology tradeoff. By 2020, ROK active duty military manpower was projected to decline from 690,000 in 2004 to 500,000, or almost a 28% reduction. To offset this reduction, DRP 2020 was to replace aging combat equipment (tanks and fighter aircraft and combat ships) with new equipment, and also add surveillance and command/control systems to significantly improve ROK military capabilities. To pay for these systems, the military budget was projected to increase by almost 10 percent per year through 2010, and then have further significant increases such that the roughly KRW 21 trillion budget of 2005 would grow to roughly KRW 55 trillion in 2020, with the force improvement portion of the budget (research and development plus acquisition) growing from KRW 5.3 trillion in 2005 to roughly KRW 20 trillion by 2015.

Unfortunately, the military budget never reached the targets set in DRP 2020. By 2011, the KRW 31.4 trillion is roughly KRW 5 trillion short of the original target for 2011, and most of the 2011 shortfall is in the force improvement budget (KRW 3.3 trillion). Moreover, because the defense budget is usually increased by a percentage over the previous year’s budget, this shortfall will propagate to all future years, leaving the aggregate 2006 to 2020 budget perhaps KRW 80 trillion short of the planned KRW 621 trillion, again with most of this shortage in force improvement. The originally planned weapon systems and other technologies will not meet the levels targeted to offset the anticipated manpower reductions.

CHANGING FORCE REQUIREMENTS

When DRP 2020 was prepared in 2005, the focus of the effort was on countering a North Korean invasion of the ROK. Against that scenario, a technology versus manpower tradeoff was quite possible. To invade the ROK, North Korean forces would have to expose themselves in ways that improved surveillance and weapon systems could clearly counter.

But since 2005, the weaknesses of the North Korean state have forced the ROK and US governments to consider alternative future force requirements. In particular, there has been substantial attention placed on a North Korean collapse scenario in which the ROK decides to achieve Korean reunification. This scenario requires stabilization and related military efforts that are manpower intensive and not as amenable to technology tradeoffs. As a result by 2009, MND had modified DRP 2020 to seek a larger active duty force (517,000 personnel) in 2020. Moreover, MND adjusted the plan that would have reduced the 47 active and reserve Army divisions to 28 divisions in 2020. It added 10 reserve divisions (38 total) that would focus on stabilization activities in the aftermath of a North Korean collapse. While these manpower increases would partially offset the lower technology advances as constrained by the military budget, the capabilities of ROK reserve forces are limited by their having at most three days of training each year.

The biggest change in military force requirements was associated with the ROK Marines. In 2005, DRP 2020 included a reduction of 4,000 personnel from the ROK Marine Corps. The independent units in the Northwest Islands were planned to be dropped and the ROK Marines 2nd Division spread out to cover that area in addition to the Kimpo Peninsula (the Northwest Island were a minor consideration in defending against a North Korean invasion of the ROK). The shelling of Yeonpyeong Island in November 2010 and the Cheonan sinking both suggested that the ROK Marine forces on the Northwest Islands need to be strengthened, not reduced.

THE ORIGINS OF DRP 307

North Korea sank the ROK warship Cheonan in March 2010. Two months later, ROK President Lee Myung-bak formally launched a National Security Review Commission to advise him on how to strengthen the ROK military, with particular focus on dealing with North Korean provocations. The sinking of the Cheonan and the North Korean artillery attack on Yeonpyeong Island in November demonstrated a number of ROK weaknesses in defenses, command/control, and in ROK military attack responses to such provocations.

Over time, the Commission prepared a series of recommendations for both short and long-term improvements in ROK military capabilities. A key recommendation was to return the draft service period to 24 months. This recommendation was so important that President Lee chose to act before receiving the final Commission recommendations; he chose to compromise and freeze the period at the current level of 21 months. The Commission recommendations also addressed rebalancing the military, resolving defense inefficiencies, and closing the gap between military and civilian society. In late December 2010, the Commission provided the President with some 71 recommendations in its final report. Minister Kim Kwan-jin added two recommendations and started MND work on the recommendations.

Moving quickly, MND prepared many of the recommendations for immediate action, especially given the needs for countering North Korean provocations. The conclusions announced on March 8 reflected initial policy decisions, with the details for implementing the policies often yet to be worked out. Still, the policy decisions set a course for ROK military modernization that is important and helpful in dealing with North Korean challenges.

SHORT-TERM COUNTERS TO NORTH KOREAN PROVOCATIONS

North Korea’s provocations have tended to take advantage of ROK military weaknesses and gaps in capabilities. Thus the submarine that sank the Cheonan was not detected before the attack and was apparently able to escape after the attack, while the ROK had little ability to respond promptly to the shelling of Yeonpyeong Island.

There are three areas where the ROK can prepare to counter future provocations: prevention, command and control, and retaliation/punishment. The Defense Reform 307 Plan includes elements of each. The 307 Plan is focused on a ROK “proactive deterrence” strategy to deter North Korea provocations, in part by helping the ROK avoid serious damage from North Korean provocations and in part by being able to retaliate effectively against provocations. The ROK is effectively trying to change North Korean assessments of its provocations to anticipate that the costs of provocations will be greater than their benefits (the logic of deterrence).

Prevention

In December 2010, the ROK repeated the artillery live fire training that led North Korea to attack Yeonpyeong Island. But this time, the ROK amassed considerable air, sea, and ground power to counter any attack by North Korea. Despite making very serious threats before the firing, North Korea decided not to attack Yeonpyeong Island again, convincing some in the ROK that North Korea is a “paper tiger” (it will threaten but not take action if the ROK is adequately prepared to respond).

Some of the ROK preventive effort reflected enhancements of ROK Marine capabilities on the Northwest Islands. MND is adding K-9 artillery, 130 mm multiple rocket launchers, counterbattery radars, precision (Spike) missiles, and light attack helicopters. It will also increase the number of Marines by 2,000 this year, and has talked about increasing the 5,000 active duty Marine personnel on the Northwest Islands to 12,000 personnel of all services, though Marines would likely constitute the vast majority of this number. But to do so without losing personnel from the other ROK Marine divisions, the Marine personnel would need to increase a further 3,000 or so personnel (beyond the 2,000 for this year), and the ROK Army opposes this change, feeling that any added Marine personnel will mean reduced Army personnel.

The Northwest Islands will also be organized into a new 3-star command, with the ROK Marine Commandant designated the commander. This considerable rise in the status of the Northwest Island forces may also contribute to deterrence (from a cognitive perspective).

Command and Control

One of the biggest problems the ROK experienced in responding to the 2010 provocations was with command and control. The ROK military command structure was clearly not prepared for either of the two provocations, and functioned very poorly.

MND has taken several measures to overcome these problems. First, the Defense Minister has directed all forward units that they, “…should take action first and report up the chain of command afterwards if North Korean forces launch an attack against them.” This authorizes responses in kind and other defensive responses, which could include sinking a submarine like the one that attacked the Cheonan (to prevent it from firing torpedoes).

The Minister has also appeared to approve some degree of escalation in response to North Korean provocations: “Minister Kim also encouraged commanders to have a creative mindset in foreseeing possible enemy attacks and translate their ideas into action. ‘Use your imagination to counter attacks. We need to have constant discussions to predict possible North Korean provocations,’ he said.”

Moreover, the ROK military has historically had a dual-track command system, command flowing to both the JCS Chairman and the Service Chiefs of Staff. This arrangement complicated provocation responses. The 307 Plan retains the JCS Chairman in overall command, but places the ROK Service Chiefs (Army, Navy, and Air Force) directly under him as operational commanders, providing a single-track command system. Moreover, for the first time the ROK JCS Chairman will have selective control on Service personnel issues such a promotions. The result is a strengthening of the ROK JCS Chairman.

This approach will help solve the 2010 command failures, but it raises new concerns. The new arrangement will give greater power to the ROK JCS Chairman, who has almost always been a ROK Army officer. Many ROK Navy and Air Force officers therefore fear greater ROK Army dominance in the military. In particular, they worry about the dissolution of many independent Service functions. They fear that eventually the ROK could adopt a unified military without service distinctions, allowing the ROK Army to take full control of the ROK military. For example, the previously separate senior service colleges will be consolidated into a single senior service college as part of the 307 Plan, and the Service Academies will likely be consolidated over time, as well. To expedite any response to future provocations, a National Crisis Management Center was set up under control of the Blue House (not controlled by MND). This organization will provide direct support to President Lee in dealing with future provocations, and also provide a focus for interagency coordination across the ROK government.

Retaliation/Punishment

The ROK is seeking significantly enhanced military capabilities to retaliate against North Korean provocations in the future. To provide enhanced intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, the ROK wants to sign a procurement contract for Global Hawk unmanned aircraft by the end of 2011. The ROK also wants to acquire stealthy fighter aircraft to more safely carry out attacks against North Korea, hoping to make a purchase by 2013. And it is acquiring more precision munitions like JDAMs. These air delivered munitions would allow the ROK to destroy North Korean artillery protected in underground facilities, and also reach and destroy many other potential targets with precision, thus limiting attack size and collateral damage.

Analyzing These Responses to Provocations

Should North Korea decide to carry out further provocations, these ROK improvements could significantly increase the military costs imposed on the North. This would be particularly true against North Korean attacks on the Northwest Islands. But these improvements would not prevent damage to the ROK. To do so would require the deployment of active defenses in addition to these artillery, aircraft, and related strike capabilities. Active defenses could include an artillery intercept system like the Israeli Iron Dome or the US Army lasers under development (MND may eventually pursue such systems).

The ROK military has focused heavily on developing military attack responses to North Korean provocations. But because the North Korean provocations appear to be primarily motivated by North Korea’s internal politics (seeking to demonstrate regime empowerment to help secure regime survival and succession), military attack responses may not be adequate to make the North Korean regime perceive that the costs of provocations will be greater than their benefits (the normal criterion for deterrence). The ROK government also needs to be formulating political responses to the North Korean provocations.2

It will be particularly difficult to deter North Korean provocations when North Korea selects provocations that make ROK/US military attack responses difficult, as it has in recent years. The nuclear and ballistic missile tests of 2006 and 2009 were generally not perceived as warranting a military attack response, nor have the North Korean cyber attacks and the more recent jamming of GPS in the area north of Seoul. The North Korean attack on the Cheonan was plausibly deniable, and thus failed to warrant a military attack response. And the shelling of Yeonpyeong Island was justified by North Korean territorial claims, making it difficult at the time to execute responses other than immediate in kind responses.

North Korea will likely pursue future provocations that also make a ROK attack response difficult. They could again employ nuclear and ballistic missile tests. And North Korea could attempt to use submarines again to attack ROK naval ships. Alternatively, North Korean special forces could be used to covertly attack targets in the ROK, seeking plausible deniability that complicates military attack responses.

The Defense Reform 307 Plan does not appear to address very well North Korean provocations against which military attack responses are difficult to justify. In particular, active defenses against North Korean provocations seem to have received inadequate attention. For example, while the ROK and US forces have done exercises to improve antisubmarine warfare capabilities, the open discussions of the 307 Plan do not include acquisition of enhanced submarine detection sensors for use in the West Sea. The open discussions indicate that MND plans to acquire an Israeli-made early warning system for ballistic missile launches and a missile defense control center. But the ship-based missile interceptors needed to intercept a North Korean ballistic missile test are too expensive for the ROK military now and likely will not be acquired until after 2015 at the earliest. Finally, there does not appear to be a part of the 307 plan that would counter North Korean infiltration of and actions by special forces.

Of course, MND may be working on these potential gaps but just not openly discussing its efforts.

BUILDING MEDIUM- TO LONG-TERM CAPABILITIES

The Defense Reform 307 Plan includes many activities that will strengthen the ROK military’s medium- to long-term capabilities. They reportedly include:

- Increasing the number of K-9 self-propelled howitzers, and building K-2 tanks and K-21 infantry fighting vehicles.

- Increasing the quality and number of counterbattery radars.3

- Acquiring means to protect Seoul from North Korea’s long-range artillery.

- Enhancing ballistic missile defense in the ROK.

- Extending military basic training from 5 to 8 weeks.

- Fielding an Air Force ability to provide 24/7 airborne surveillance and early warning of an enemy infiltration using AWACS and UAVs.

- Changing conscription to provide about 55,000 more military personnel in 2020 than with an 18 month conscription period, or about 575,000 total.

- Creating a special reserve force for national emergencies with 10,000 reserve personnel. They will train two days per month, and focus on national emergencies and not war (but would likely be useful in a collapse situation).

- Extending the annual training periods for reservists. The current training period for reservists in their first five years (roughly 1.5 million personnel) of 3 days and 2 nights will be expanded to 4 days and 3 nights in 2016 and 5 days and 4 nights in 2020. For 5th and 6th year reservists, training will be extended from 18-20 hours to 36 hours in 2020.

REBALANCE MILITARY FORCES, SEEKING JOINTNESS

MND will take a number of actions to rebalance the ROK military forces. It will rebalance the general officers on the JCS and at MND to roughly a 2:1:1 ratio (Army:Navy:Air Force) from the current roughly 3:1:1 ratio. It will similarly rebalance the ratio of colonels. The size of the ROK Army will be reduced by 2020, potentially to the roughly 400,000 planned in the latest version of Defense Reform Plan 2020. This would yield a total ROK military of somewhat over 500,000. The ROK Marines will be made more independent of the ROK Navy, but not an independent service on their own.

A number of actions will also increase jointness. The integrated command structure under the ROK JCS chairman and the integration of the Service colleges are two examples.

RESOLVE DEFENSE INEFFICIENCIES

MND will strive to reduce defense inefficiencies. This includes reducing generals by 15%, and more generally reducing non-combat duties to allow more active duty personnel to be associated with combat units. Where needed, civilian personnel will replace active duty military personnel performing non-combat functions. The military will establish a system to evaluate the qualifications of officers and give them certificates for combat skill qualifications. Promotions will be tied to these new programs.

CREATE CLOSER LINKS BETWEEN MILITARY AND CIVILIAN SOCIETY

MND will strive to “Create a military which is respected by the public” and “instill the belief that the troops are being properly treated by the nation.” It will reduce officer and especial general officer perks. It will “enhance security education for citizens.” It will establish a committee on weapons requirements with civilian representation.

OVERALL ASSESSMENT OF THE 307 PLAN

The details of the 307 Plan thus far released suggest that it will clearly provide strengthened weapons and selected other capabilities for the ROK military. The enhanced ROK strike capabilities and defenses of the Northwest Islands will be important advances, as will many of the mid- to long-term capability improvements. Nevertheless, the 307 Plan does not appear to redress the serious budget reductions suffered by the Defense Reform Plan 2020. The ROK military will be strengthened by new weapon systems, but it is not clear that these new systems will adequately offset the reduction in ROK military manpower or allow the ROK to become more militarily self-reliant (a major goal for a decade or more).

It is hard to evaluate the results of the planned force improvements given the apparent lack of a ROK military force structure plan as a target for the years 2020 and 2030. MND has yet to disclose the manpower targets for active duty, reserve, and civilian personnel in these future years (except for vague references to “about 500,000” active duty personnel in 2020). The 307 Plan has not defined the number and character of Army divisions, Air Force fighter wings, or naval combat squadrons for these years nor the equipment needed for these units. Such plans may be in preparation and may be announced later this year. A key issue is whether MND will take advantage of the lengthened conscription period and plan a force structure closer to 575,000 in 2020, reducing manpower less than planned in 2005 and thus more consistent with the less than planned technology increases. But an increase in the planned number of conscripts could have significant manpower costs.4

It is also unclear how MND will meet the requirements for officers and NCOs (professional personnel) contained in the National Defense Reform Act of 2006. Article 26 of that act requires each Service to have over 40 percent of its manpower as officers and NCOs in 2020. The ROK Air Force and Navy have already achieved this percentage, but the ROK Army is well short of this level (still less than 25 percent officers and NCOs). The 307 Plan needs to clarify how it will meet this mandate of the law.

The 307 Plan also needs to define the forces required for dealing with a North Korean government collapse that leads to unification. A collapse and unification would tend to require more manpower than a defense against a North Korean invasion, and be less susceptible to manpower versus technology tradeoffs. From a US perspective, the key area of concern is defining the forces required to rapidly eliminate North Korean weapons of mass destruction (WMD). If, for example, the US and ROK Presidents call for eliminating all North Korean nuclear weapon capabilities within 1 week of becoming involved in a collapse, would the ROK and US forces have appropriate and sufficient forces to perform such an assignment? Would they also be able to secure the 200 or so key nuclear scientists and research personnel? Besides dealing with WMD, would ROK and US forces be adequate to disarm the North Korean military and stabilize North Korea? Would the right forces be available to interact with senior North Korean military personnel and secure their cooperation? What work needs to be done before a collapse to accomplish these goals?

The ROK military has traditionally emphasized combat forces and paid less attention to support forces. Despite similarities in the overall manpower in each Army, the ROK Army has fielded 47 divisions (active and reserve) compared to fewer than 20 division equivalents in the US Army active and reserve forces (though US divisions have more manpower than many of the ROK divisions)—the US Army has far more manpower dedicated to supporting functions. The recent NATO air strikes on Libya have also demonstrated that many US allies have limited logistical supplies (for example, even France and Britain have been reportedly running out of precision munitions despite fighting only a short, relatively low intensity conflict). Will the ROK have the logistics and other support required for the months to years likely needed to stabilize North Korea after a conflict or collapse? Also, the ROK has not fielded trucks like the US MRAP that protect against the use of IEDs; won’t the ROK military require such capabilities?

Finally, the 307 Plan needs to establish reserve force requirements in terms of capabilities and force structure. With the number of ROK young men available for military service due to significantly decline by 2025, the ROK reserve forces need to be prepared to fill the resultant gaps. But a relatively small fraction of the ROK reserves are organized into units or given much training each year. The reserves need to be organized to provide needed units (such as those required for WMD elimination), and the personnel in these units professionalized with more annual training (in many cases more than the increases included in the 307 Plan). In addition, the ROK needs a legal framework for declaring a selective mobilization so that a protracted stabilization effort in North Korea will not cause the ROK economy to largely shut down.

CONCLUDING WORD ON DETERRENCE

For years, the ROK security community has emphasized the importance of deterring North Korean attacks. While the ROK has increased its military capabilities, many in the Korean military still argue that US military presence in the ROK and the US extended deterrence/nuclear umbrella commitment do more to deter North Korea than all that the ROK military could do, even with a vastly increased military budget. More work is needed on how to use ROK and US military forces to deter North Korean provocations and other attacks.

perspective in 1946, arguing that with the introduction of nuclear weapons, “Thus far the chief purpose of our military establishment has been to win wars. From now on its chief purpose must be to avert them. It can have almost no other useful purpose.”5 While Brodie was focused on the impact of nuclear weapons on modern combat, more broadly speaking the advanced societies of the 21st century do not want even a conventional war to occur, and certainly not a war with at least a nuclear shadow as conferred by the North Korean nuclear weapon threat. Properly posturing military forces for deterrence is thus key to both future ROK military requirements and the requirements for US military support of the ROK.

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 1

This paper represents the views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the oplinions or policies of RAND or its research sponsors.

- 2

The author’s work on “proactive deterrence” describes such actions in more detail.

- 3

The ROK is focused on radar systems more advanced than AN/TPQ-37. It has purchased a Swedish system designated “Arthur,” though other work may also be going on.

- 4

The cost of conscripts is low today because they are paid very little. But there are some calls for paying conscripts at least the minimum wage, which would greatly affect the military budget—by about KRW 4 trillion or so today.n

- 5

Bernard Brodie, “Implications for Military Policy,” The Absolute Weapon: Atomic Power and World Order, Harcourt Brace, 1946, p. 76.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter