Issue Watch:

Guide to Key Policy Concerns in South Korea for 2014 1

Fifty million South Koreans bid farewell to 2013 and welcomed in the lunar New Year on January 31st. Now is an opportune moment to look back and think ahead about key issues that will dominate policy concerns in Korea during the Year of the Horse. In this brief, we list eight that are worth a closer look (in no particular order): i) History and Korea-Japan Relations; ii) North Korea and Inter-Korean Relations; iii) Wartime Operational Control; iv) the Korea-US Civil Nuclear Cooperation Agreement; v) the China Question; vi) Trade; vii) Economic Outlook; and viii) Domestic Politics.

1. History and Korea-Japan Relations

We begin our discussion with an issue that has vexed pundits and leaders in this part of the world. There can be little argument otherwise—2013 was a low point in relations between Japan and Korea. Unfortunately, 2014 does not look to be any brighter as controversy continues around the interpretation of history among these two unlikeliest of bedfellows.

The issue dates back to Korea’s independence from Japanese imperial rule in 1945 and it includes Japan’s position on the issue of “enforced sex slave (i.e. Comfort Women)” as well as territorial claims to the island of Dokdo, among others. The salience of this issue has varied with time but it has certainly fueled tensions between these two countries in 2013 as Prime Minister Abe continued his visit to the Yasukuni Shrine and questioned the use of coercion to recruit “sex slaves” during World War II.2 The issue looks to gain steam again as a number of events approach in the coming months ahead: Takeshima Day (February), announcements on Japanese textbooks (March), and the Yasukuni Shrine spring festival (April). The Korean Supreme Court is also about to rule on a case involving compensation by Japanese firms on forced Korean labor during the occupation.

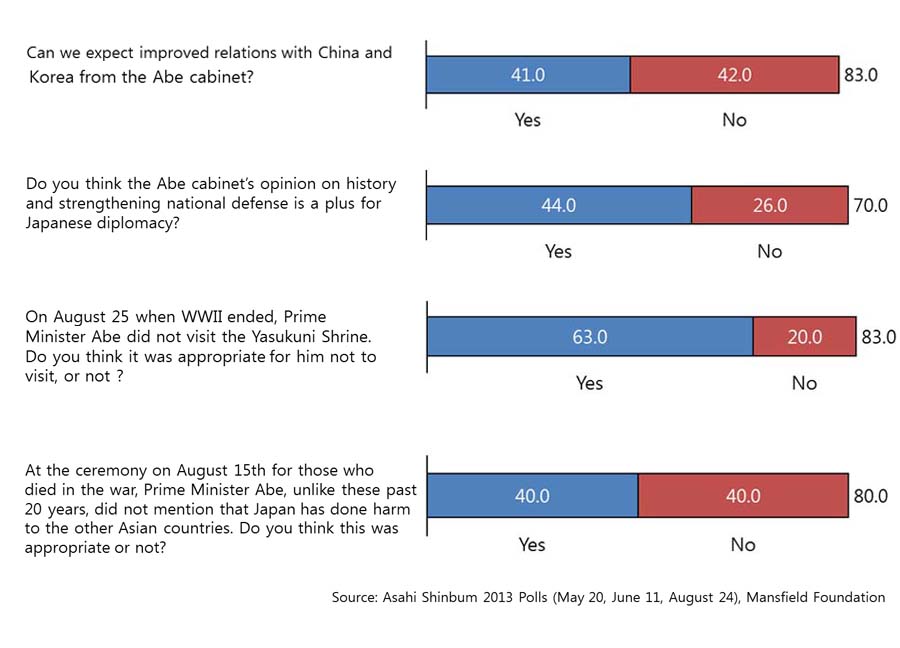

A number of critics in the United States, Korea, and China have suggested that Japan tone down its rhetoric and behavior but PM Abe does not appear willing to do so. While the United States has refrained from taking a strong position on this sensitive issue, observers in the region see a more active US intervention on this matter as a sine qua non for a way forward. One thing is clear, regardless as to what the leaders in Japan or Korea want from this relationship, both will have a difficult time compromising on the issue of history given the strong domestic position on this issue that keeps the two nation apart (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Public Opinion on Korea-Japan Relation

2. North Korea and Inter-Korean Relations

Speculations ran rampant immediately following the controversial purge of Jang Song-thaek in December 2013. Some even spoke of a possible regime collapse in North Korea;3 however, the passing of time has shown that the newly-installed Kim Jong-un regime emerged even more centralized and stable after the purge. Question remains, however, as to how North Korea or inter-Korean relations will change (if at all) in the post-Jang Song-thaek era.

While the South Korean government has left open the possibility of future dialogues with the North, the South’s policy of trustpolitik hinges on Pyongyang undertaking the necessary steps to move towards denuclearization. Going by all indications thus far, it seems that North Korea has no intention of doing this. If anything, Kim Jong-un’s latest public statement suggests that it is South Korea that must take the necessary steps towards engagement given North Korea’s latest gestures towards warmer relations.4

In the aftermath of the third nuclear test, the emerging consensus among pundits is that North Korea possesses several working nuclear devices but it still has some way to go until it can master the capability to miniaturize and deliver a functioning warhead over a long distance.5 What this means, of course, is that the allies have time to prepare or even hinder North Korea from ultimately achieving this goal. One suggestion by pundits is to raise the level of sanctions on North Korea to comparable restrictions placed on other countries like Iran.6 Others have suggested further strengthening deterrence capability against a nuclear North Korea.7 Considering a more extensive and seamless integration of the Korean Air and Missile Defense System (KAMD) and the US-led Ballistic Missile Defense System (BMDS) may prove useful. Whatever measures the allies decide to adopt, one thing is clear—preparations are needed to deal with the inevitable reality of a nuclear North Korea.

3. Wartime Operational Control (OPCON)

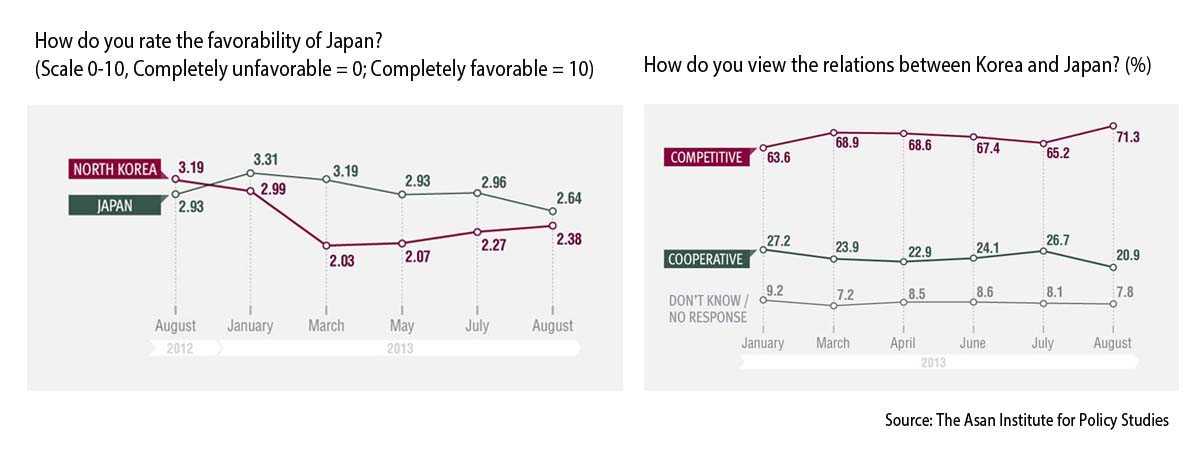

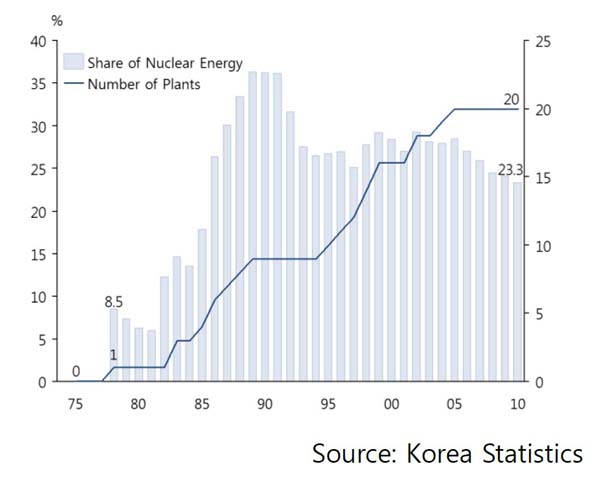

The 2007 agreement on the transfer of wartime operational control (OPCON) from the United States to Korea was originally set for April 2012; but faced with increasing provocation from North Korea (i.e. a failed rocket launch and the second nuclear test in 2009 as well as the sinking of the South Korean corvette Cheonan) the two countries agreed to push this deadline back to December 2015. With the shelling of Yeonpyeong Island in 2010 followed by a successful rocket launch in December 2012 and a third nuclear test in February 2013, the Park administration is once again requesting the United States to further delay OPCON transition to a date later than 2015. Proponents of the delay argue that 1) OPCON transfer sends the wrong signal about the allies’ resolve to deter future provocations; 2) South Korea is not ready to play the leading role in the event of an open confrontation with the North; and 3) that this move will weaken the joint defense readiness of the allies.8 Those who advocate maintaining the current course argue that South Korea is fully capable of defending the country on its own and OPCON transfer does not mean any reduction of US military presence or strategic commitment to the region given the binding nature of the ROK-US Mutual Defense Treaty. Korean public opinion on this issue, however, suggests that about 57 percent of respondents support the idea of the United States maintaining wartime operational control (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 South Korean Public Opinion on OPCON Transfer

4. The Korea-US Civil Nuclear Cooperation Agreement (i.e. 123)

The two year extension on the Korea-US Civil Nuclear Cooperation, also known as the “123 Agreement,” has been approved by Congress and is likely to be signed by the president. But the talks on a new agreement between the United States and South Korea will resume in 2014. The main point of contention between the two parties is South Korea’s demand to reprocess its spent fuel rods. The United States has been reluctant to go along with this proposal because of concerns over proliferation—one of the byproducts of reprocessing is plutonium that can be weaponized. Without Seoul taking any interim measures, however, South Korea will reach its spent fuel storage capacity by 2016. Hence, a new agreement is of the utmost priority for Seoul.

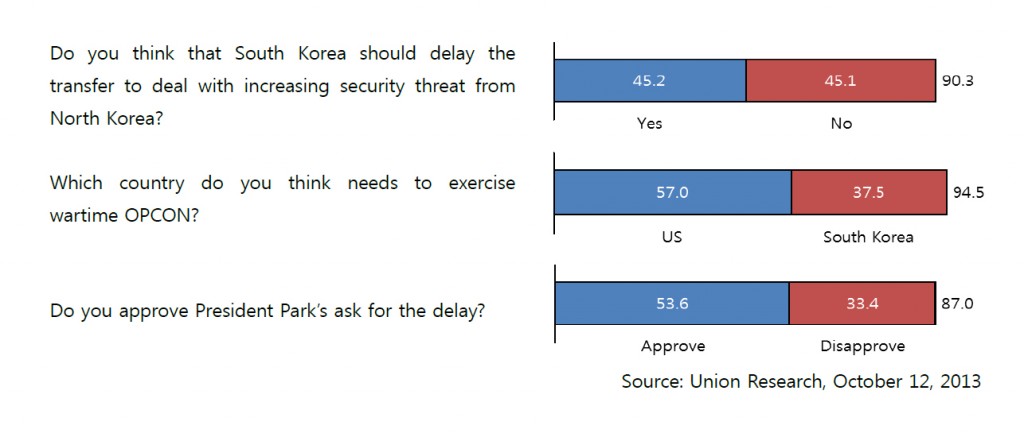

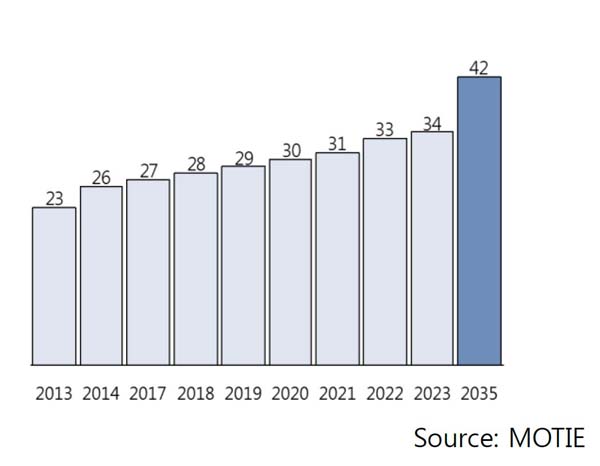

Korea’s demand for revision results from changed circumstances since the agreement was first signed in 1974. South Korea has become the fifth largest nuclear energy developing country with 23 reactors and seven new plant constructions planned for the near future.9 It also wishes to establish its reputation as a full service provider, who can build new reactors in countries like the UAE where it has already signed a contract worth over US$20 billion. Without the ability to reprocess, however, South Korea sees itself at a competitive disadvantage when compared to other nuclear energy supplying nations.

Even more disconcerting is the possibility of disruption to a stable domestic energy supply. The existing plan is to make nuclear power account for 29 percent of the country’s total energy generation by 2035. That target is higher than the current share of about 26 percent but lower than the former administration’s goal of 41 percent.10 Safety concerns following the Fukushima disaster and domestic safety scandals account for the dip. Priority has moved on to acceptability, stability, and environmental impact rather than economic benefits and stable supply.

Figure 3 Trends of Nuclear Energy Development and Plants, 1975-2010

Figure 4 Nuclear Energy Reactor Construction Plan, 2014-2035

To meet the new goal, Seoul needs to take control of 40-42 reactors by 2035. This means constructing 17-19 additional plants. As of today, there is a plan in place to complete 11 new constructions by 2023 with five constructions already under way.

5. The China Question

The meaning of China’s rise in the region is also a serious concern for Korea, especially given the relationship that the PRC maintains with North Korea. The silver lining here is that diplomatic relations between China and South Korea have never been better. In 2012, the two countries celebrated the 20th year of normalized diplomatic relations. During the PRC-ROK Summit in June, Presidents Park and Xi agreed to establish various channels for strategic dialogue as well as to strengthen cooperation on matters related to the economy, energy, marine environment, and culture. Much of this feel good mood is largely based on the deep economic tie that these two countries have with one another. China is South Korea’s largest trading partner and South Korea is China’s third largest.

Good economic relations between China and South Korea, however, must come to terms with the reality of security ties that South Korea maintains with the United States and China has with North Korea. For South Korea, China holds the key to North Korea’s nuclear problem, given how much the latter depends on the former (both economically and militarily). On the other hand, to no one’s surprise, South Korea is a close ally of the United States. The ROK-US Mutual Defense Treaty, which is the basis for stationing 28,500 US servicemen in Yongsan and Osan, is no secret to anyone including China.

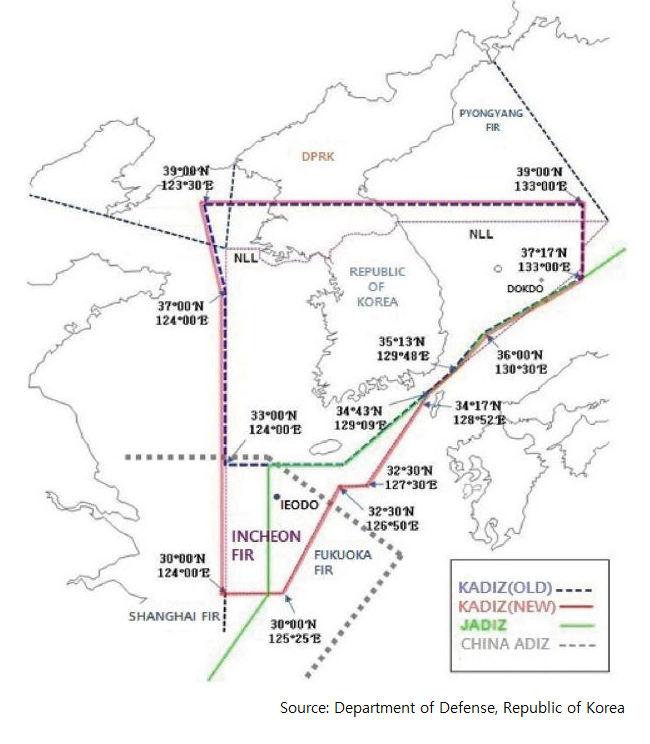

China has shown, however, that it can manage or even make use of this duality to its advantage. Take the issue of China’s declaration of its Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) over the East China Sea in November 2013. Japan’s response was to reaffirm its own ADIZ, which includes the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, and refuse recognition of China’s ADIZ. Korea also worked in consultation with the United States to expand its ADIZ to include Marado, Hongdo, and Ieodo. Seoul’s declaration of South Korea’s own ADIZ was not without controversy as two positions emerged over the debate regarding this move.11 The proponents of an international legal perspective argued that Korea must move to make its ADIZ claims clear and unequivocal, given the importance of precedent in international law. Those who interpreted the ADIZ issue less as a legal problem rather than a political one argued that Korea should wait and see how the dispute gets settled between Japan and China before it can claim the territory in the East China Sea. These two positions, though well intentioned, however, miss a critical dimension in the ADIZ debate—namely, the effect that the overlapping ADIZs (see Figure 5) has on the US-Japan and ROK-US alliance. If we examine the ADIZ issue through the alliance prism, Japan is perhaps the most disadvantaged given its contradictory position with regard to Diaoyu/Senkaku in the East China Sea and Dokdo in the East Sea. The South Korean ADIZ includes Dokdo but the Japanese ADIZ does not. If using strict legal interpretation, Japan’s position on the island is likely to be problematic and could serve as an additional point of friction in Japan-Korea relations. If this was a calculated move on China’s part, as we argue, then it has done well in driving a deeper wedge between Korea and Japan, thereby making the US position in between these uneasy partners even more discomforting.

Figure 5 CJK-ADIZ

The ADIZ issue is but one of many examples (i.e. TPP and North Korea) where China’s diplomatic moves were carefully measured to take advantage of the weakness in the US-led regional alliance—namely, Korea’s growing economic dependence on China and the deteriorating relations between Japan and Korea. How Korea will fare against China’s increasing sophistication and influence will remain one of the key foreign policy issues in 2014 and beyond.

6. Trade: China-Korea FTA, TPP, and RCEP

South Korea has quietly expanded its network of bilateral and multilateral free trade agreements (FTAs) with major trading partners over the past decade. And this trend is not likely to change any time in the near future.

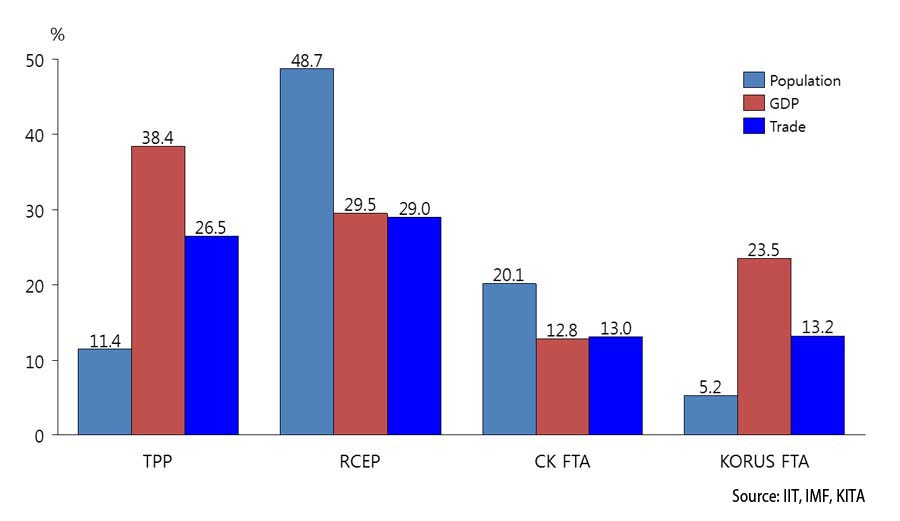

Following the conclusion of successive FTAs with the United States and the European Union, Korea looks to complete the signing of a bilateral FTA with China (CK FTA) by the end of 2014. Given that China is Korea’s largest trading partner, the gains from this agreement are expected to be a boon for the Korean economy.12 The biggest hurdle in the negotiation process is expected to be the offsetting incentive for the domestic agricultural sector, which has the most to lose. If Korea successfully concludes this deal, however, it would be the only country in the world to have successfully negotiated a free trade agreement with the three largest economies.

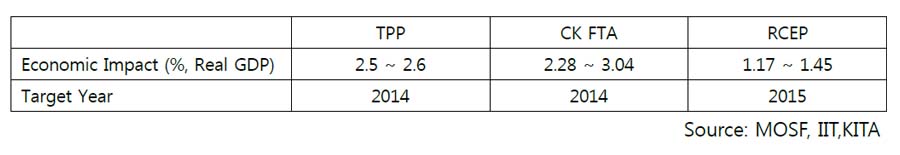

Aside from the bilateral FTA with China, Seoul also looks to be an active player in a regional integration regime. To this end, South Korea has publicly announced its interest in joining the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in November. Given that Korea is negotiating or has negotiated bilateral FTAs with most of the member nations, there was some debate about TPP’s importance for Korea. While the gains from TPP will depend on the quality of the agreement, experts generally agree that it would increase Korea’s real GDP by 2.5-2.6 percent over 10 years after its enactment.13 Korea’s commitment, on the other hand, will depend on the hurdles for regulatory harmonization and the kinds of safety nets that the government can provide for adversely affected sectors of the economy.

Aside from TPP, Korea is a participant in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) led by China. Experts estimate the general economic impact to be modest (1.17%-1.45%) given the wide disparity among negotiating countries (see Table 1).14 There is a question, of course, about the overall quality level of this agreement given the difficulty in generating consensus. Japan, for instance, proposed a target of 90 percent tariff reduction plus concessions over 10 years during the second round of negotiations, but other countries such as China, India, New Zealand, Australia, Myanmar, and Cambodia disagreed with this proposal for various reasons. Meanwhile, South Korea expects the CK FTA to serve as a benchmark for raising the overall quality of the RCEP just as the KORUS FTA has for the TPP.

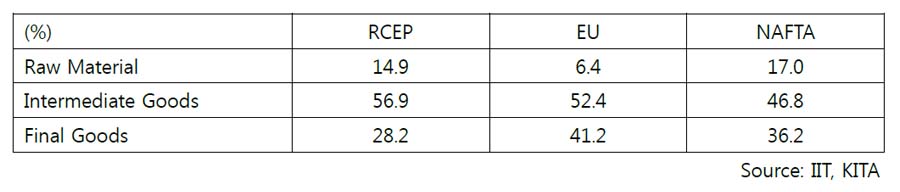

All three agreements are critical to South Korea’s strategy of wanting to expand and maximize gains from trade. Since Korea’s exports are mostly intermediate goods (67.6% in 2011), increased efficiency gains in the production network would be the biggest benefit derived from multilateral FTAs.

Figure 6 Comparison of TPP, RCEP, CK FTA and KORUS FTA

Table 1 Comparative Economic Impact (Over 10 Years Post-Implementation)

Table 2 Share of Intra-Regional Trade by a Type of Goods, 2011

7. Economic Outlook

The Ministry of Strategy and Finance (MOSF) has announced this year’s goal as “Economic Revitalization and Social Stability.” More specifically, the operationalization of these objectives mean a focus on growth and job creation. The projected real growth for 2014 is 3.9%.15 If the prediction bears fruit, this would be the first time that South Korea’s growth surpasses that of the world over the past decade. To facilitate the current recovery, MOSF vows to keep the expansionary fiscal policy in place and manage external risks, such as increased volatility in the international financial market arising from the end of Quantitative Easing (QE) in the US and uncertainties in the Japanese economy, among others.

Some observers in the region worry that the Federal Reserve’s recent decision to end its expansionary monetary policy will possibly lead to higher interest rates and lower global demand for Asian exports. Some observers point to the declining value of emerging market currencies (e.g. South Africa, Mexico, India, and Brazil, among others) as a sign of more ominous future.16 The government, on the other hand, has maintained that the negative impact from austerity measures in the US would be limited given Korea’s strong economic fundamentals. Nonetheless, the administration has assured the investors that it will closely track the developments in the US and take additional measures to minimize negative shocks and further strengthen the domestic economy.

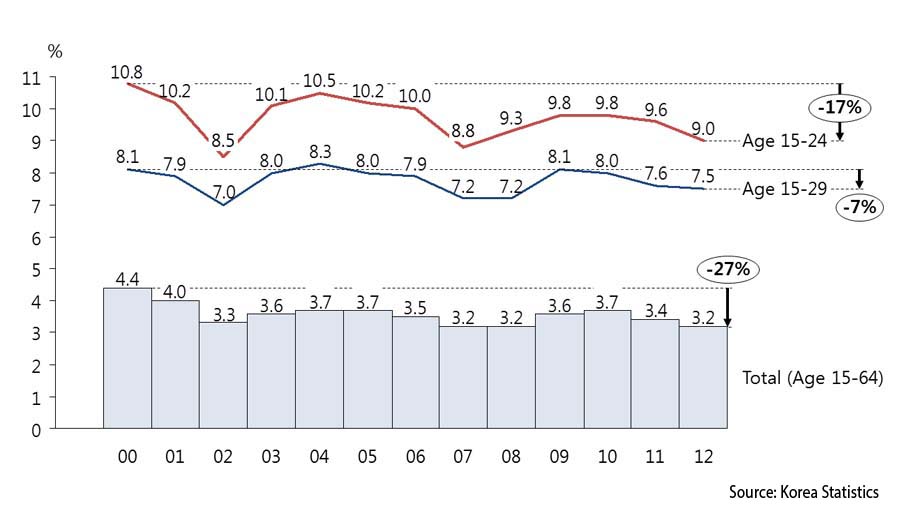

One key area of improvement is in youth employment. While South Korea has one of the lowest unemployment rates among OECD nations, it lags behind other countries like Austria, Japan, Norway, and Switzerland when it comes to youth unemployment. With regard to youth labor force participation, South Korea has the second lowest total within the OECD. Experts attribute this statistic to the high ratio of school attendees and NEET (Not in Education, Employment and Training) population. As of 2011, 65 percent of the age group between 25 and 34 are university graduates, the highest figure among OECD countries. Regarding a share of NEET population among the youth aged between 20 and 24, South Korea recorded the 7th highest number, or 23.5 percent, among OECD countries (see Figure 7).

Figure 7 Unemployment Rate, 2000-2012

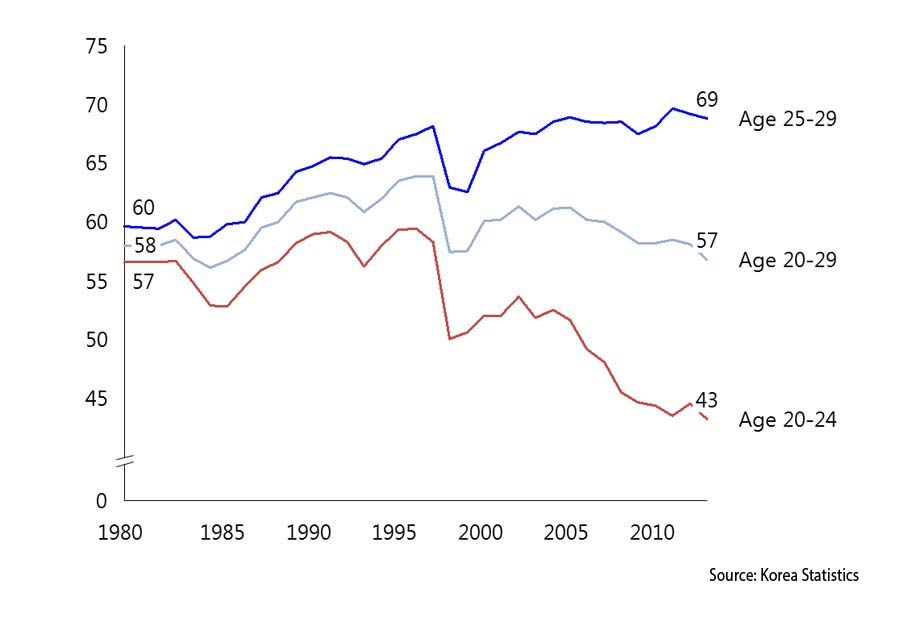

Pundits suggest that this trend does not bode well for the Korean economy in the long run. First, the decline in youth labor force participation means an overall rise in the average working age in Korea. In fact, the average worker is now 44 years old, which is an increase of 5.1 years from 1990.17 The trend does not look to change anytime soon if the past is any indication of the future (see Figure 8). The implication here is that job creation is lagging behind labor supply.18 Lack of jobs among educated youths means less productivity for the overall economy.

Figure 8 Trend in Youth Employment, 1980 -2012

8. Domestic Politics

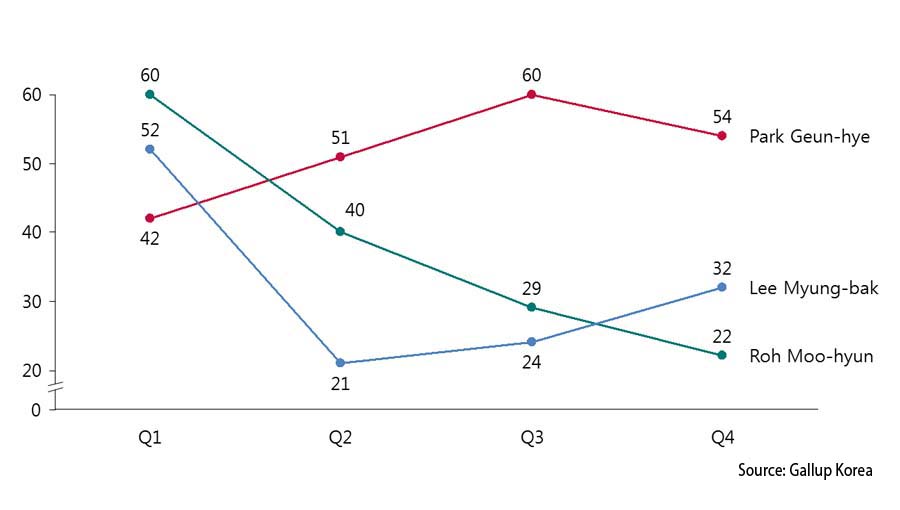

President Park Geun-hye basked under high approval ratings during her first year in office. Although it was a bumpy start with troubled nominations for her cabinet, her performance during the successful summit meetings with the United States, China, and Russia as well as the reopening of the Kaesong Industrial Complex seem to have paid dividends. During the Q3 and Q4, however, she recorded several setbacks related to tax reform and social spending. But her first-year approval is relatively stable compared to her predecessors (see Figure 9).

Figure 9 Comparative Approval Rates of the First Year of Presidency

In the New Year’s speech, President Park placed special emphasis on economic reform with her announcement of “the three-year economic reform plan”, details of which are to be disclosed in March. The plan has three items on the agenda: public sector reform, creative economy, and linkage between domestic and global economy.

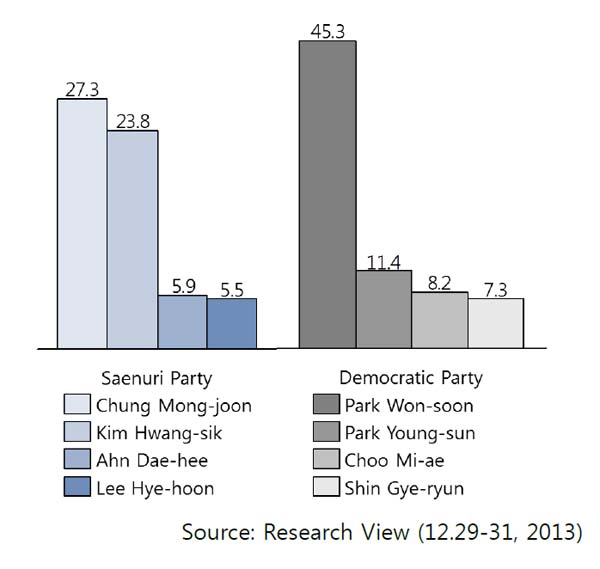

Local government elections are also scheduled for June 4th. The importance of this election cannot be downplayed given that many people in Korea consider this to be a midterm referendum. There is a special focus on the Seoul mayoral race as many observers see this position as a potential steppingstone for the presidency. The current mayor, Park Won-soon, is a clear frontrunner (see Figure 10). But a possible dark horse entry by Ahn Cheol-soo’s new party may result in a split vote situation where the Saenuri Party candidate can emerge as the winner. Current frontrunners in the ruling party include Chung Mong Joon, Kim Hwang-sik, General Ahn Dae-hee, and Lee Hye-hoon (see Figure 10). As of January, only Lee has announced her candidacy for the primary.

Figure 10 Seoul Mayor Candidates Approval

Conclusion

If 2013 was a year of transition, 2014 looks to be a year of action. With the conclusion of a long honeymoon period, the Park administration is expected to come under heavier scrutiny as observers look to see whether the government will follow through with necessary reforms to reinvigorate the economy and strengthen national security. Foreign policy issues related to the changing dynamics within the region also presents a new challenge for the administration in figuring out how to press ahead in maintaining its longstanding alliance with the United States.

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 1

The authors would like to thank Dr. Choi Kang and Dr. Kim Jiyoon for their helpful comments and feedback.

- 2

“Risky Nationalism in Japan”, New York Times, December 26, 2013; “Japan NHK boss under fire for comfort women remark,” Washington Post, January 27, 2014.

- 3

“Grasping for Clues in North Korean Execution,” New York Times, December 13, 2013; “North Korea confirms purge of Kim Jong Un’s uncle, describes ‘anti-state’ crimes,” Washington Post, December 9, 2013.

- 4

Choe Sang-hun, “North Korea Agrees to Proposal to Resume Family Reunions, Reversing Stance,” New York Times, January 24, 2014; “buk shinmun sinroe barandamyeon oese haek kkeuroedeurigi jungdanhaeya handa,” Donga Ilbo, February 3, 2014.

- 5

Siegfried S. Hecker, “North Korea reactor restart sets back denuclearization,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, October 17, 2013; Siegfried S. Hecker, “What to Expect from a North Korean Nuclear Test,” Foreign Policy, February 4, 2013; Terrence Roehrig, “North Korea’s Nuclear Weapons: Future Strategy and Doctrine,” Policy Brief, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, May 2013; Markus Schiller, Characterizing the North Korean Nuclear Missile Threat (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2012); Markus Schiller, Robert Schmucker, and J. James Kim, “Assessment of North Korea’s Latest ICB Mock-Up,” Issue Brief, The Asan Institute for Policy Studies, January 14, 2014.

- 6

Go Myong-hyun, “North Korea as Iran’s Counterfactual: A Comparison of Iran and North Korea Sanctions,” Issue Brief, The Asan Institute for Policy Studies, Forthcoming.

- 7

Schiller et al.

- 8

US-Korea Institute at SAIS, 2006 SAIS US-Korea Yearbook.

- 9

MOTIE, “je 2cha Energy gibon gyehoek,” Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, January 2014.

- 10

Ibid.

- 11

“[Dongbuga sin paegwon gyeongjaeng] banggongguyeok hwakdae naseon hankuk, jung•ilgwa oegyomachal gamsu taese,” Chosun Ilbo, November 30, 2013; jeongbu, “banggongguyeok hwakdaean 12wol cheotjjaeju nae gongsik balpyohal keot”, Donga Ilbo, December 4, 2013.

- 12

Expert estimates of gains from trade range from 2.28 to 3.04 percent depending on the quality of the agreement; MOSF, “hanjung FTA hyeopsanggaesi seonoengwa hanjungFTAui gyeongjejeok hyokwa”, Ministry of Strategy and Finance Press Release, May 2, 2013

- 13

Peter A. Petri and Michael G. Plummer, “The Trans-Pacific Partnership and Asia-Pacific Integration: Policy Implications,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, June 2012; MOTIE, “bodochamgojaryo-TPP gongcheonghoe gaechoe (11.15) gyeolgwa,” Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, November 15, 2013.

- 14

IIT, KITA, “Current Status and Outlook on RCEP,” Trade Brief, no. 34, Institute for International Trade, Korean International Trade Association, October 1, 2013.

- 15

MOSF, “2014nyeon gyeongjejeonmang”, Ministry of Strategy and Finance, December 27, 2013.

- 16

“The Fed and emerging markets: The end of the affair,” The Economist, June 15, 2013.

- 17

Jung Sunyoung, “ingugujo byeonhwaga goyonge michineun yeonghyang,” Issue Paper Series no. 2013-15, the Bank of Korea, October 2013.

- 18

Park Sejun, Park Changhyun, Oh Yongyeon, “gyeonggi-goyonggan gwangye byeonhwaui gujojeok yoin jindangwa jeongchaekjoek sisajeom,” Issue Paper Series no. 2013-8, the Bank of Korea, May 2013.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter