Introduction1

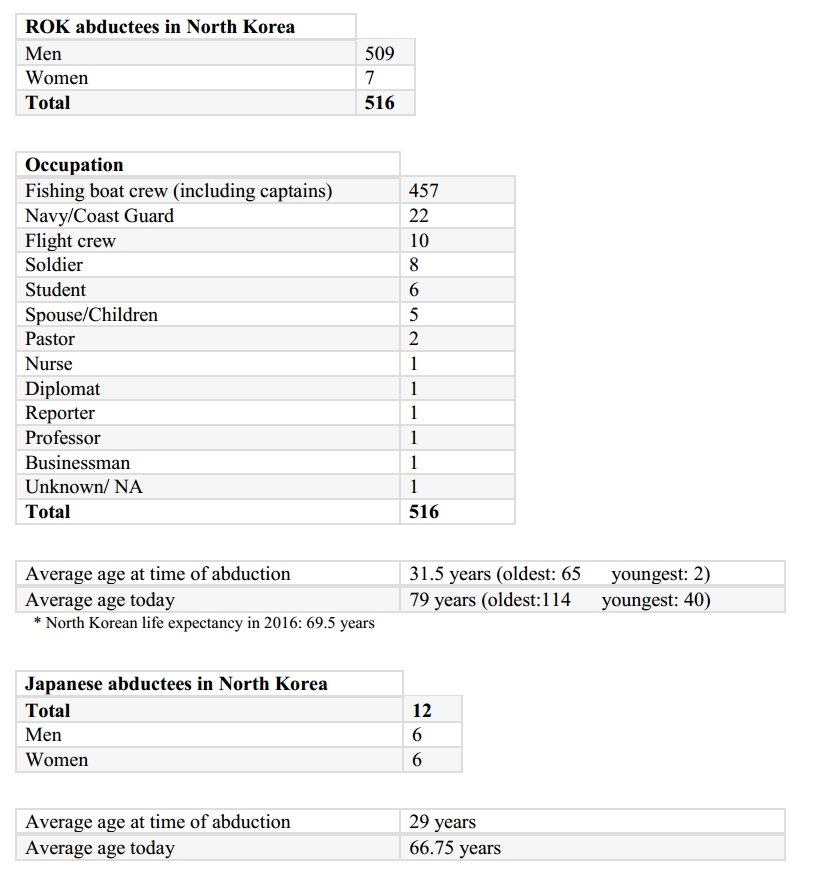

Since the end of the Korean War, there have been at least 143 incidents of abduction by North Korea involving 3,835 South Koreans.2 Of this number, 3,319 were released or successfully escaped back to the South. However, as of today, there are still 516 South Korean nationals held in the North.

North Korea’s policy of abducting citizens from the South is older than the country itself. On July 31, 1946, Kim Il-sung stated: “Not only do we need to search out all of Northern Chosun’s intelligentsia in order to solve the issue of a shortage of intelligentsia, but we also have to bring Southern Chosun’s intelligentsia [to the North].”3 Beginning with this announcement, which sanctioned the abduction of South Korean intellectuals, three generations of Kim leaders have pursued a policy of kidnapping civilians from the South to further the goals of the regime.

These abductions were not random acts initiated by rogue operatives. They were authorized at the highest level. The ample use of different organs of the state, including army, navy, special-forces, and the intelligence services indicate that abductions were systematic and fully supported by the regime. Originally envisioned by Kim Il Sung as a way to bolster the North’s human capital stock, the regime soon realized that abductions served both strategic and propaganda purposes in its standoff with the South. The impunity with which the abductions were carried out, especially in the West Sea (Yellow Sea) emboldened the regime and put the South Korean military on the defensive. Hundreds of South Korean abductees, an absolute majority of them impoverished fishermen, were also useful foil for the North Korean propaganda machine.

When Kim Jong Il emerged as the heir apparent to his father in the mid-1970s and extended his influence over the North Korean state, he took personal control of the power agencies within the state, and his preferences were soon reflected in a range of policy matters, including North Korea’s abduction programs. With Kim’s personal touch, the operatives for the North Korean regime soon embarked on a risky strategy of abducting foreigners and South Koreans alike from well beyond the peninsula.

But the North Korean abduction spree came to an end with the end of the Cold War. With the collapse of the Eastern Bloc, North Korea was left politically and economically isolated, and as a result, the regime lost the ability to stage abduction operations in far flung places. In more recent years, the regime has only been able to operate in the Chinese provinces that border North Korea.

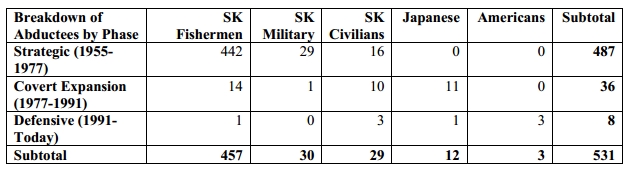

As the North Korean regime altered its strategic goals amidst the changing international environment, their policy of abducting South Koreans and other foreign nationals evolved to fit their overall foreign policy goals. Over the years, the regime’s kidnapping campaign went through three phases: the strategic phase, the covert expansion phase, and the defensive phase. While no specific event perfectly delineates these phases, each coincided with changes in the broader international environment.

Strategic Phase: 1955-1977

According to the South Korean government, of the 516 abductees still detained in the North, 487 (95%) were taken during the 22-year period from 1955-1977. Compared to later years, North Korea’s abduction methods during this time were exceptionally disruptive, brash, and unambiguous. Most of these abductions took place within South Korea itself or its territorial waters. Several occurred inside or close to the DMZ. The abduction policy during this period was part of a wider plan to wreak havoc in South Korea and prepare for a renewed attempt to reunify the peninsula by force. It was also a strategy by which Kim Il Sung hoped to secure the legitimacy of his regime while simultaneously delegitimizing the government in Seoul. To understand the importance of abductions in the “Strategic Phase,” one must look at the wider state of affairs on the peninsula at the time.

The years following the Korean War were difficult throughout the peninsula, with both Koreas struggling to rebuild the infrastructure and recover the human capital lost during the war. As Kim Il Sung realized in 1946, the South possessed the greater number of intellectuals, an asset the North sorely needed if they were to revitalize their struggling economy. To attract them, the North Korean leadership either needed to persuade these intellectuals to defect or bring them to the DPRK by force. But early in his reign, Kim’s widespread purges of “enemies of the state” quickly extinguished any hope of coaxing the southern intellectuals to defect.

Even the North Korean elite were abandoning the regime. Increasingly fearful of the punishments that befell those who lost Kim’s favor, several prominent North Korean officers posted overseas and a dozen North Korean exchange students studying in the USSR defected.4 The regime made several attempts to kidnap these “non-returnees” and was successful in abducting at least one postgraduate student at the Moscow School of Music who had applied for asylum. The student, Yi Sang Un, was reportedly seized in broad daylight and sent back to Pyongyang.5

In addition to reigning in their own defectors, North Korea soon used abductions as a means to achieve another goal of the regime: recruiting spies. North Korea needed spies to disrupt South Korea, foment dissention, and prepare for what they assumed would be an inevitable resumption of the war. As the South struggled economically, remaining heavily dependent on U.S. assistance, Kim Il Sung continued to believe that the South Korean people would rise up against their government if North Korea could prove itself to be the superior system. South Koreans kidnapped during this time were indoctrinated with pro-North propaganda, but ultimately only two were sent back to South Korea as spies, only to be promptly caught by the authorities.6

This phase reached its apex during 1966-1969, a period sometimes referred to as the “Second” Korean War, for its low level, guerilla warfare-style skirmishes along the border. In January 1968, North Korea captured the USS Pueblo, a U.S. navy intelligence ship, in international waters and held its crew captive for 11 months. That same year saw the audacious Blue House7 raid and a number of other infiltration attempts into the South. During these tense years, North Korea kidnapped South Korean civilians at an unprecedented rate. Of the 516 South Korean abductees in the north today, 133 were taken in 1968 alone. These abductions, skirmishes, and raids sought to draw South Korean and U.S. resources away from the Vietnam War while sowing as much confusion as possible and testing the resolve of the ROK-U.S. alliance.

On December 11, 1969, North Korea executed its most audacious abduction scheme. A North Korean agent hijacked a Korea Airlines flight and forced the pilots to land in Pyongyang. After 66 days, 39 of the 46 passengers were allowed to return to South Korea. But the four crew and seven remaining passengers were not allowed to leave. They were kept in North Korea because they had skills that could be of use to the regime. Their families and friends never saw them again.8

To illustrate how North Korea justified their actions to the world, it is helpful to look at a specific case of how their diplomats spun the events. On February 15, 1974, two South Korean fishing vessels, the Suwon-ho 32 and Suwon-ho 33, were attacked by the North Korean navy. The former boat was sunk while attempting to escape and the latter was captured. Later that month, the UN Military Armistice Commission held a meeting with the North Koreans to discuss the issue. The two sides’ retelling of the incident is revealing.

UN: At 1003 hours, Suwon-ho 33 radioed ashore that its location was as indicated by the picture, clearly in international waters, some 30 nautical miles from North Korea. It also reported that one of your side’s gun boats had opened fire from a distance of approximately 1 mile. As a result of this unprovoked attack, the Suwon-ho 32 was sunk. […] Following this your gun boat forced the innocent, unarmed Suwon-ho 33 to accompany it toward North Korea.

DPRK: The spy boats of your side disguising themselves as “fishing boats” doggedly refused to comply with the repeated demand of our People’s Army naval vessel on routine patrol duty in the Western Sea for their withdrawal from our coastal waters. […] Upon the disclosure of their true colours, your side’s spy boat “Suwon 32″ hurriedly veered to the southwestward to flee and rammed her stem against our naval craft which was just turning sideway and another spy boat “Suwon 33″ was captured by our side on the scene of the incident.9

In February 2014, forty years after he was kidnapped, Choi Young Chul, one of the crewmen of the Suwon-ho 33, was allowed to briefly reunite with his relatives during one of the rare gatherings of separated families organized by the North and South Korean governments.10 For most families of abducted fishermen, however, the fate of their loved ones remains unknown.

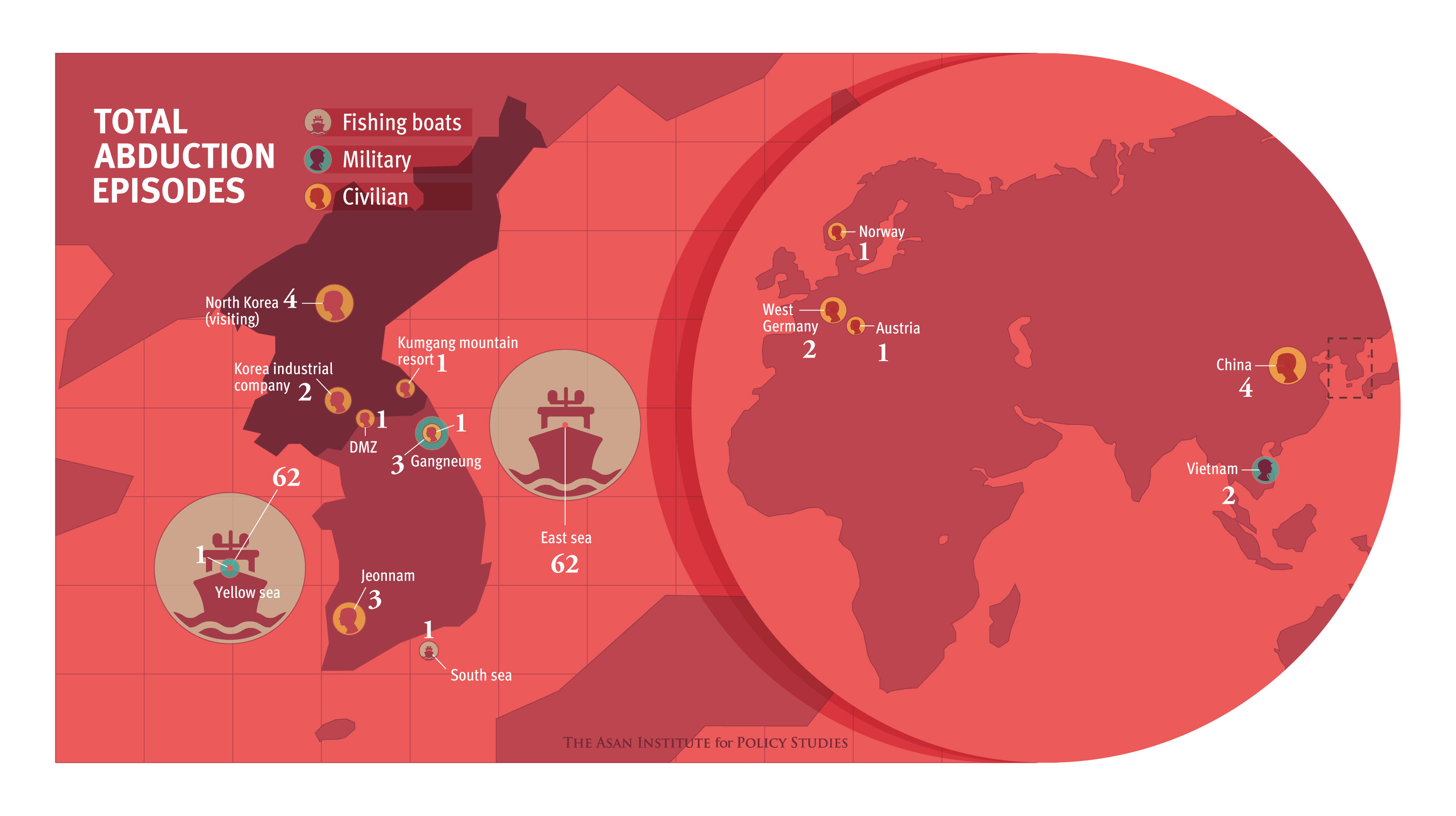

Figure 1. Total Abduction Episodes by Location

Covert Expansion Phase: 1977-1990s

Beginning in the mid-1970s, the nature of North Korean abductions of South Koreans changed significantly. The mass abduction of South Korean fishermen virtually ceased by 1975, but it was followed by the first abduction of Japanese citizens in 1977. While the overall number of abductions declined, the geographic scope of the abductions expanded, as the regime’s agents went beyond the peninsula to abduct their victims. South Korean citizens from as far away as Europe and North Africa were now targeted, and the regime begun to systematically abduct non-Koreans, especially young Japanese. This change in North Korea’s abduction strategy coincided with the changes in the international environment at the time and the internal power dynamics within the regime.

First, North Korea could no longer maintain an aggressive stance against South Korea and the United States. The U.S.-USSR détente was well under way by the early 70s, and the growing Sino-Soviet schism prompted the two Communist behemoths to explore better relations with the U.S. separately. With its two patrons shying away from direct confrontation with the United States, North Korea could no longer sustain its aggressive strategy targeting the South. As a result, the situation in the peninsula became relatively stable, which led to the first attempt at an inter-Korean dialogue since the end of the Korean War.11

Along with the improvement in inter-Korean relations, South Korea improved its defenses in the West Sea. In the mid-70s, South Korea deployed French-made Exocet anti-ship missiles in the West Sea, creating a significant deterrence effect against North Korean incursions. In addition, more patrol ships were deployed to protect the fishing vessels, lowering the chance of successful hijackings by North Korea.

Internally, the rise of an ambitious young leader within the regime meant a change in direction in North Korea’s overall abduction policy. Perhaps reflective of his own preference for maintaining a low public profile, Kim Jong Il changed the nature of North Korea’s abduction strategy from overt to covert. And Kim also took a personal interest in the abduction targets. He was directly responsible for the most famous abduction case, that of South Korean actress Choi Eun-hee and her husband, director Shin Sang-ok, in 1978. The two were used by the regime to produce propaganda films until they escaped in 1986.

Kim played a major role in the abductions of South Koreans and other foreigners via his web of agents. According to the report by the UN Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (COI-DPRK) published in 2014, the overseas kidnappings were carried out by Office 35 of the Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea, an intelligence bureau controlled by Kim Jong Il. (Other abductions along the ROK and Japanese coastlines were ordered through the Director-General of the KPA Reconnaissance Bureau.)12 The stakes were high for the North Korean agents tasked with abducting South Koreans. The former deputy director of the North Korean spy agency allegedly claimed that agents who failed to abduct their target could face execution.13

Abductions or abduction attempts of South Koreans by North Korean agents were made in Iraq (1977), West Germany (1971 and 79), Norway (1979), Paris (1977 and 79), Hong Kong (1978), Karachi (1979), Beirut (1986), and various other locations in Japan, Yugoslavia, Austria, Libya, and Egypt.14 Most of these victims were students or skilled professionals. They were chosen for their knowledge and expertise, which the regime exploited. North Korea perpetrated abductions in these far-flung locales in order to limit the risks of infiltrating South Korea directly. Kidnapping in a third country also allowed the regime to plausibly deny any involvement if their agents were compromised. In contrast to the “Strategic Phase,” the regime was emphatic in avoiding exposure, rather than fomenting havoc.

However, this did not mean that South Koreans were secure in their own country. Five South Korean high school students were abducted from beaches in the South in the summers of 1977 and 1978. Only one has since seen his family, during a brief reunion in 2006.15

Also during this time, North Korea abducted at least 17 Japanese civilians from Japan between 1977 and 1993, with the bulk of the abductions taking place in the 1977-1980 period.16 Of the 17 victims, five were eventually able to return in 2002. Like the South Korean abductees, Japanese citizens were brought to North Korea to serve the interests of the regime, namely teaching the Japanese language and cultural practices to North Korean spies. Others were given as brides to foreigners living in North Korea. When Kim Jong Il admitted this to Japanese Prime Minister Koizumi in 2002, it set off popular outrage in Japan, which to this day remains the most contentious issue in their bilateral relations.

In the late 1970s, North Korea also kidnapped an unknown number of foreign women from Europe, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia. The fates of many of these women are unknown.17

Table 1. Breakdown of Currently Held Abductees by Phase

Defensive Phase: 1990s-today

With the collapse of the North Korean economy in the 1990s, the regime’s ability to conduct complicated missions abroad was severely curtailed. It also became increasingly difficult to abduct citizens from South Korean and Japanese coasts, as both countries modernized their maritime defenses. Packaging abductions as defections for propaganda purposes also lost its meaning, as North Korea’s economic situation became increasingly desperate, and even the North Korean public stopped believing the regime’s propaganda.

The current period can be described as the “Defensive Phase,” for North Korea’s kidnapping strategy over the past twenty years has focused on individuals who posed a direct threat to regime stability. For this end, North Korea has targeted North Korean defectors and South Korean religious and human right activists working in the Chinese-North Korean border region, specifically those helping North Koreans defect to South Korea.

Abducting and bringing the victims to North Korea across a porous border is not a logistical challenge for the agents. The “cost” of abduction operations is thus relatively low, and as a result, abduction plays a valuable role in state security policy. Those captured and brought to North Korea likely face harsh retribution by the regime.

Such was the case of Jin Gyeong-suk, a North Korean defector with South Korean citizenship who returned to the China-North Korean border in August 2004. According to her family, Mrs. Jin was on her honeymoon and had returned to the North Korean border to try to smuggle in some presents for her relatives. At some point, a group of North Korean men forcefully seized her and dragged her into North Korea. However, a month after the incident, the South Korean National Intelligence Agency disputed these events. They claimed that Mrs. Jin had actually been at the border in order to film North Korean opium farming, and that her abduction was unconfirmed. Despite the family’s protests, she was never added to the official government list of abductees. The following January, Mrs. Jin’s mother, who had also defected to the South, received news from an acquaintance in North Korea that her daughter was dead.18

Another well-known abduction case is that of Kim Dongsik, a South Korean pastor captured in China in 2000 after two years of work in the border regions helping defectors escape to South Korea. He was approached by a female North Korean agent claiming to be a defector. After gaining his trust over the span of several months, she lured him to a restaurant where he was taken by other agents across the border. He is reported to have died the following year after months of mistreatment and torture.19

And if the victim can’t be taken, even more brutal methods can be applied. A Korean pastor, Han Choong Yeol, was found murdered near the Chinese-North Korean border in April 2016, having faced threats from the North Korean agents for years as he worked in the region. Chinese police investigated allegations that he was murdered by two North Korean agents who have since slipped back across the border, but the case remains unsolved.20

According to the South Korean government, only three of the 516 abducted citizens left in North Korean captivity were taken since 1995, although the actual number is almost certainly much higher. The UN has listed more than a dozen cases of Chinese and South Korean citizens kidnapped by North Korea’s State Security Department from the late 1990s to early 2000s.21

In May 2016, the South Korean Ministry of Foreign Affairs held a meeting with representatives from ten major travel agencies in South Korea. They had been summoned for a briefing on the threat posed by North Korean agents abducting South Korean citizens in northern China.22 The meeting was prompted by a series of threats from the North Korean regime to kidnap South Korean citizens abroad as “retaliation” for a mass defection of workers from a North Korea-owned restaurant in China the previous month. One source claimed as many as 300 North Korean agents had been dispatched to the border regions in China to track and abduct unwitting South Korean tourists and activists.23 These agents will sometimes work a single case for months or even years in order to gain the trust of their victims before the abduction takes place.

North Korean regime’s use of abduction for propaganda and ensuring external security has continued under Kim Jong Un. Recently, there has been an increasing number of North Korean defectors “voluntarily” returning to the North. South Korea’s Ministry of Unification reported that, as of 2016, there were 19 confirmed cases of defectors “voluntarily” returning to North Korea24. Although some may indeed have returned on their own, there is increasing concern that some may have been forced to return against their will, likely because of the regime’s threats against their family members remaining in the country. The fact that the returning defectors are often shown on state TV denouncing South Korea while praising the regime increases the likelihood that the North Korean authorities are orchestrating the “voluntary” return of defectors for propaganda purposes.

Conclusion

South Korea has few viable options to ascertain the whereabouts of their abducted citizens, let alone repatriate them. North Korea either insists that the abductees have defected to the North voluntarily or refuses to acknowledge that they were taken in the first place. And the tendency by the South Korean government to downplay the abductee issue to focus on the larger goals of denuclearization and unification only exacerbates the problem of collective amnesia about the abductees.

While the world is looking the other way, North Korea has continued to use abductions as a foreign policy tool. In fact, it may be entering a fourth phase in which the regime unlawfully detains foreigners who enter North Korea voluntarily. Today, North Korea holds three foreign citizens in detention for what it claims are crimes against the state. Three are Korean-American: Kim Dong Chul (since 2015), Kim Sang-duk (since 2017), and Kim Hak-Song (since 2017).25 One, a Korean-Canadian pastor, Lim Hyeon Soo, was released in 2017 after being detained in 2015.26 American detainees like these have been used as bargaining chips by the regime to leverage high level meetings from American leaders, as when former President Bill Clinton visited Pyongyang in 2009 to free American journalists Laura Ling and Euna Lee.

But the North Korean regime may have overplayed its hand. An American college student, Otto Warmbier, who had also entered the country voluntarily but was detained by the North Korean authorities for arbitrary reasons in 2016, died soon after being released to his family in June 2017, having apparently suffered catastrophic brain damage during the early stage of his detention. While his death galvanized the American public opinion and put the spotlight back on the issue of abductees, his case is baffling, as releasing him in a comatose state would have furthered no conceivable strategic aim of the regime and was thus an outlier in these detainee cases.

In order to prevent the North Korean regime from engaging in further use of abductions as a policy tool, policy makers and the media should increase public awareness of this issue. The South Korean government and the international community in particular should take the following steps to prevent further abductions from happening in the future:

▪Discourage travel to North Korea in general, and Northern China in particular, for defectors and South Korean human rights and religious activists.

▪The South Korean government should emphasize these abduction cases on the occasion of inter-Korean dialogues and negotiations for the reunions of separated families.

▪The international community should take advantage of the exiting human rights dialogue mechanisms that North Korea has agreed to engage, such as the Universal Periodic Review process of the UN Human Rights Council, to press the issue of the abductions and compel the regime to disclose the fate of the abductees and release the survivors.

▪Countries maintaining diplomatic relations with North Korea should hold further normalization of relations contingent upon the North Korean regime’s compliance with international demands on the abductee issue.

The North Korean regime is currently engaged in the denuclearization dialogue with the United States and South Korea. North Korea may believe that it can regain the trust and respect of the international community by agreeing to curtail its nuclear and missile developments. But nations should be empathetically clear that the North Korean regime will only be welcomed back to the international community when it acknowledges its human rights violations, punishes those responsible, and compensates the victims and their families.

Appendix 1: South Korean and Japanese Abductees in North Korea

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 1. Choi Sunghan and Kim Yuri also contributed to the research for Issue Brief.

- 2. Data from the Evaluation Commission for Compensation and Support for North Korean Abduction Victims (“납북피해자 보상 및 지원 심의위원회”), a South Korean government commission established in 2007.

- 3. http://www.dailynk.com/english/read.php?cataId=nk02500&num=1967. Accessed July 20, 2017.

- 4. Andrei N. Lankov “Kim Takes Control: The ‘‘Great Purge’’ in North Korea, 1956–1960” Korean Studies, Volume 26, Number 1, 2002, pp 87-119

- 5. Ibid.

- 6. Data from the Evaluation Commission for Compensation and Support for North Korean Abduction Victims (“납북피해자 보상 및 지원 심의위원회”)

- 7. South Korean president’s residence

- 8. “Report of the detailed findings of the commission of inquiry on human rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.” February 7, 2014. Paragraph 897.

- 9. “Military Armistice Commission United Nations Command. Three Hundred and Forty-eighth meeting of the Military Armistice Commission Transcript.” Feb. 28, 1974. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/assets/media_files/000/001/642/1642.pdf. Accessed October 27, 2016

- 10. http://news.kbs.co.kr/news/view.do?ncd=2812799. Accessed October 27, 2016.

- 11. This culminated in the July 4, 1972 Joint Declaration between the two Koreas.

- 12. UN COI Report 2014. Paragraph 895-896

- 13. Committee for Human Rights in North Korea. Taken! North Korea’s Criminal Abduction of Citizens of Other Countries. 2011. p.21

- 14. 동아일보, 경향일보: various articles.

- 15. UN COI Report 2014. Paragraph 900

- 16. UN COI Report 2014. Paragraph 933

- 17. UN COI Report 2014. Paragraph 963-975

- 18. http://english.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2004/09/08/2004090861020.html. Accessed July 20, 2017. http://dailynk.com/english/read.php?cataId=nk00100&num=1080. Accessed July 20, 2017.

- 19. http://english.donga.com/List/3/all/26/239156/1. Accessed July 20, 2017. http://dailynk.com/english/read.php?cataId=nk00100&num=526. Accessed July 20, 2017. UN COI Report 2014. Paragraph 980

- 20. http://www.upi.com/Top_News/World-News/2016/05/02/North-Korea-sent-agents-to-kill-Christian-pastor-activists-say/7781462205645/?spt=sec&or=tn. Accessed October 27, 2016.

- 21. UN COI Report 2014. Paragraph 981

- 22. http://english.yonhapnews.co.kr/search1/2603000000.html?cid=AEN20160516009051320. Accessed October 27, 2016.

- 23. http://www.dailynk.com/english/read.php?cataId=nk01500&num=13913. Accessed October 27, 2016.

- 24. https://www.voakorea.com/a/3608368.html. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- 25. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/13/world/asia/north-korea-american-prisoner.html. Accessed July 20, 2017.

- 26. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/dec/16/hyeon-soo-lim-canadian-pastor-given-life-sentence-in-north-korea. Accessed April 10, 2018.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter