Ms. Park Goes to Washington:

The Seoul Take1

J. James Kim | Research Fellow

Kang Chungku | Senior Research Associate

Han Minjeong | Research Associate

October 16th marked the third time in President Park Geun-hye’s five-year term that she has held a bilateral summit with President Obama and the second time that she has done so in Washington. This meeting, coming on the heels of the August 25th Inter-Korean Agreement followed shortly thereafter by President Park’s attendance at the victory day parade in Beijing and US-China summit in September, is significant to the extent that it preceded the coming trilateral summit between South Korea, China, and Japan in November as well as the scheduled South-North family reunion in October. Aside from tending to the usual business of managing the North Korean security threat, the two leaders discussed a wide range of issues including regional relations with China and Japan, South Korea’s membership in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), and cooperation in the so-called “New Frontier” matters (i.e. global health, cybersecurity, and space cooperation).2 The timing also takes on an added significance as this may very well be the last meeting between the two leaders before President Obama’s term draws to a close in 2017. So how did the two leaders do?

Even before the dust has settled, pundits in Washington are on overdrive to provide various assessments about the results from the most recent summit. A broad survey of these analyses reveals at least two contrasting takes. One paints a rather bright picture by emphasizing new areas of cooperation, and highlighting the unity among two countries on policy matters related to North Korea and China.3 The less favorable assessments lament the lack of creativity or major deliverables with regards to the common regional security challenges.4 In particular, this view traces a rather frustrating tone about the lack of concrete action plan while recognizing the difficulty in finding novel solutions to age old problems (e.g. North Korea, Korea-Japan relations, and China).

The general public, however, appears less fragmented. In the most recent public opinion poll conducted by the Chicago Council leading up to the summit, an overwhelming percentage (83%) of Americans consider relations between the US and South Korea to be important.5 While more than half (55%) of those surveyed cite North Korea’s nuclear program as a critical threat, 70% or more prefer using diplomacy and/or sanctions to manage this problem. In the event that the US Forces in Korea (USFK) is called upon to deal with an invasion by North Korea, an all-time high 47% of the American public stated that they would support the use of US military capability.

All seems well with the alliance in Washington. But how does it fare from this side of the Pacific? This paper seeks to provide an assessment of the substantive results from the most recent US-ROK summit buttressed by our analysis of media coverage as well as the most recent Korean public opinion following the summit.

The Substance

Overall, the three summits have produced several documents, most notably the 2013 Joint Declaration in Commemoration of the 60th Anniversary of the Alliance which lays out a broad statement about the state of the alliance outlining areas of cooperation between the US and South Korea on issues such as extended deterrence, North Korean nuclear and ballistic missile threat, Korea-US Free Trade Agreement (KORUS FTA), climate change, energy, human rights, overseas developmental assistance (ODA), counter-terrorism, nuclear safety and non-proliferation, cybersecurity, and counter-piracy.6 The two joint statements on global climate change (2013) and North Korea (2015) emphasize the priority that the two leaders have placed on these issues.7 Finally, the three fact sheets from each summit highlight the various areas of cooperation, including wartime operational control (OPCON), military-to-military cooperation, FTA, partnerships in science and technology, cooperation in Syria, Iran, and Afghanistan, people-to-people ties, climate change, ODA, cyber, health, and space.8

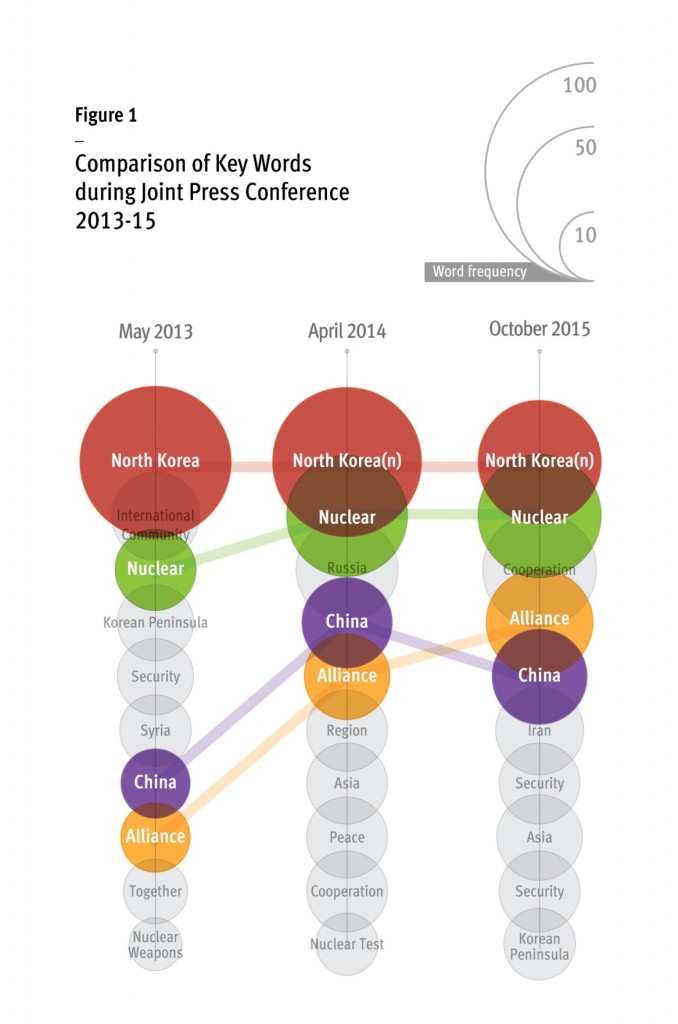

Analysis of the transcripts from the three joint press conferences by the two leaders reveals interesting patterns about the focal point of interest(Figure 1).9 Not surprisingly, there is strong resilience and sustained concentration on key issues, such as North Korea, nuclear security, alliance, and China. At times, however, other issues might require more discussion, such as Russia in 2014. This was largely due to Russia’s annexation of Crimea in March 2014 which preceded President Obama’s visit to Seoul in April 2014. In general, however, criticisms about the lack of new initiatives by the two countries should be less than surprising given how little movement there has been on these issues of mutual interest.

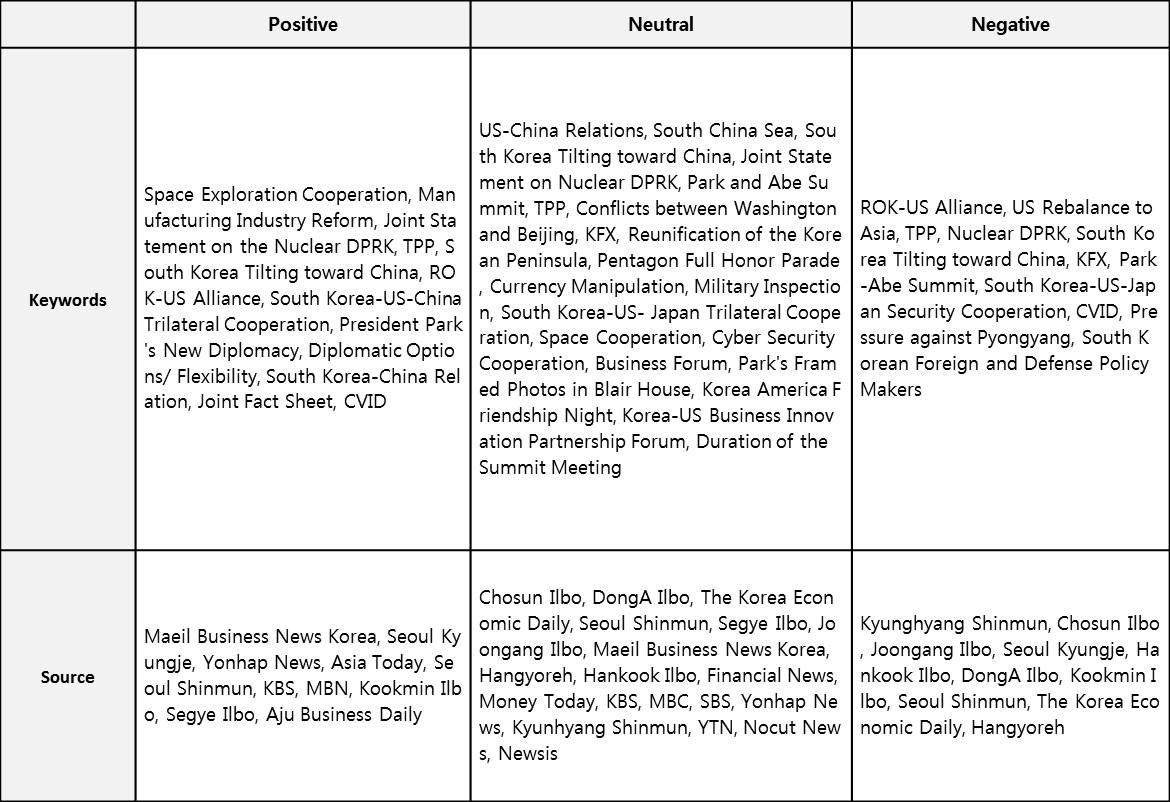

Korean media coverage also suggests that reporting about the summit were generally positive or neutral. This is not to suggest that there were no negative reporting. In fact, much of the negative press coverage were focused on the Korean Defense Minister Han Min-koo’s inability to secure export license rights for crucial technology deployed in the F-35 for application in the KF-X development program also referred to as the “Boramae Project.” Much of the criticism stems from the fact that one of the conditions for the decision to allocate $6.4 billion for purchasing 40 units of F-35s from Lockheed Martin was the understanding that the Ministry of Defense will be able to secure key jet fighter technologies. It is not entirely clear what the basis for this understanding was but this was always going to be a difficult proposition for the US. Some papers also criticized the summit for not producing a path forward for the North Korean nuclear and security dilemma. It is also interesting to note that the major media outlets, including Chosun Ilbo, Joongang Ilbo, DongA Ilbo as well as Hangyoreh did not provide any positive coverage about the summit. Much of their reporting was either value neutral or negative with Hangyoreh and Kyunghyang Shinmun making up about 43% of all negative articles.

Table 1. Korean Media Coverage of the Summit (October 16~20, 2015)10

The Public View

In terms of substance, there appears to be little daylight in the ROK-US alliance following the most recent summit. Barring minor diplomatic gaffes (e.g. KF-X), the relations between the two countries appear robust with sustained focus on key issues of mutual interest. But what does the most recent summit look like in the eyes of the Korean public? To answer this question, the Asan Institute for Policy Studies conducted a survey about the summit during October 19~20, 2015. We explore the results of this analysis below.

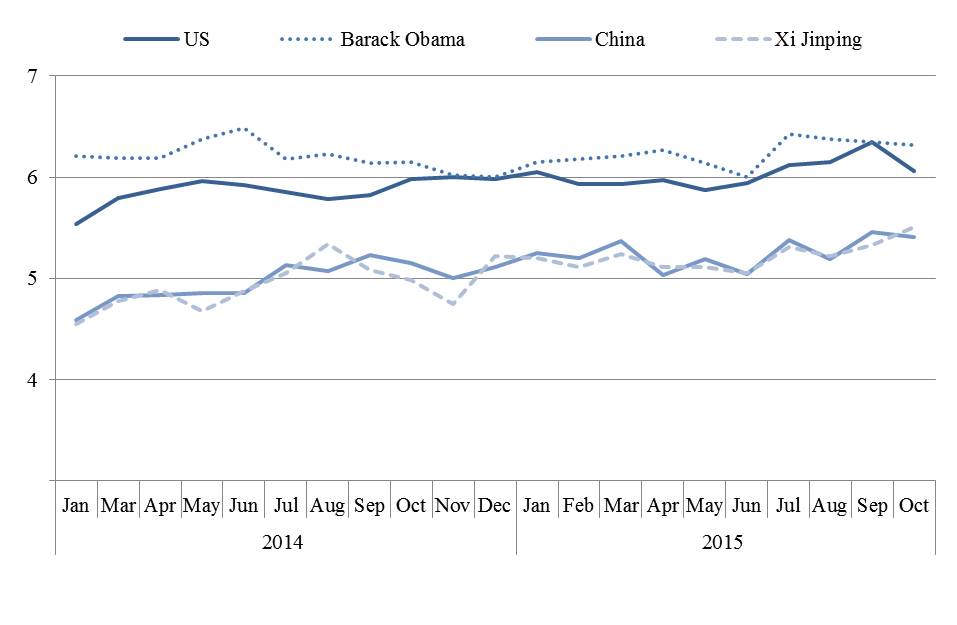

From the public’s point of view, the most recent summit was a success with over 55 percent of all Koreans expressing their approval of the meeting between Presidents Park and Obama. Not surprisingly, the overall favorability ratings for the United States and President Obama are running high. While the favorability ratings for China and President Xi Jinping have also been rising steadily, the respective scores for the two leaders are greater than two standard deviations from each other (See Figure 2).

Figure 2: Favorability11 (0:unfavorable ~ 10:favorable)

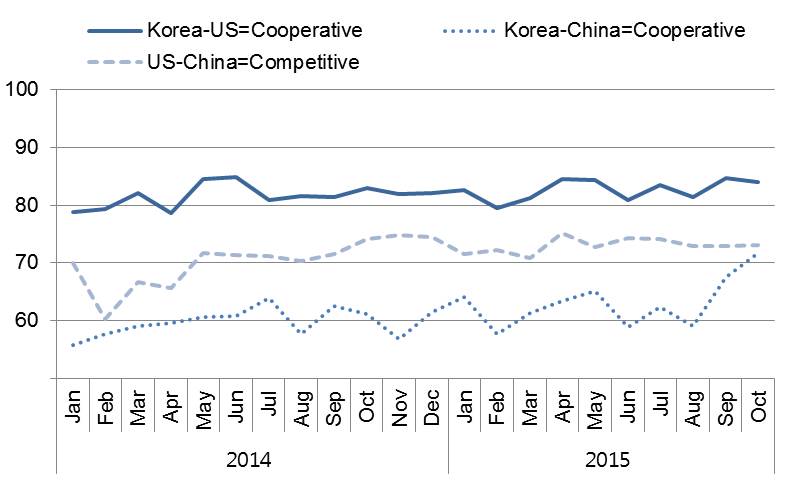

The percentage of people who characterize the Korea-US relationship as being cooperative is about 84 percent, but the most notable change is a recent sharp uptick in the number of people who see relations between Korea and China to be cooperative following President Park’s visit to Beijing in September (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Characterization of Bilateral Relations12 (%)

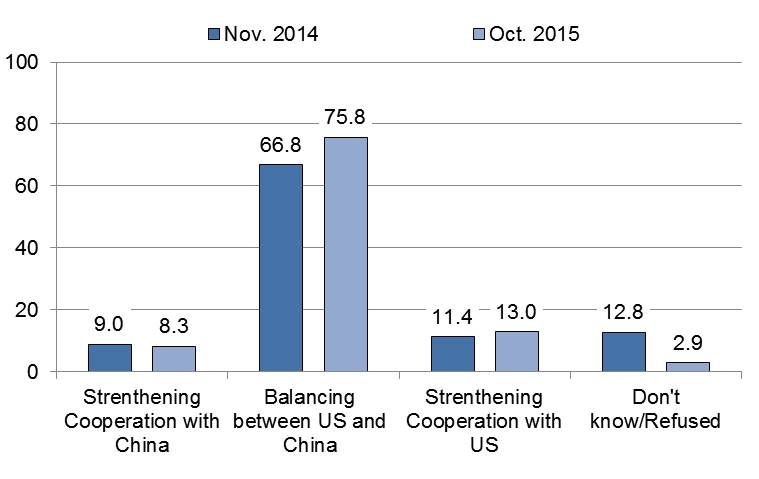

However, we do not expect to see a sustained rise in the level of positive sentiments about Korea-China relations for two reasons. One is that the public is quite supportive of the Park administration’s balanced approach to its foreign policy with respect to the US and China, which necessarily implies some ceiling on public tolerance for strengthened relations with China. This is more the case in 2015 than 2014. When we look into the source of this increase in support for a balancing approach to relations with China and the US, we notice a visible increase in bias among the 50s and older by about 17~21 percent (Figure 4).

Figure 4: South Korea’s Foreign Policy Approach13

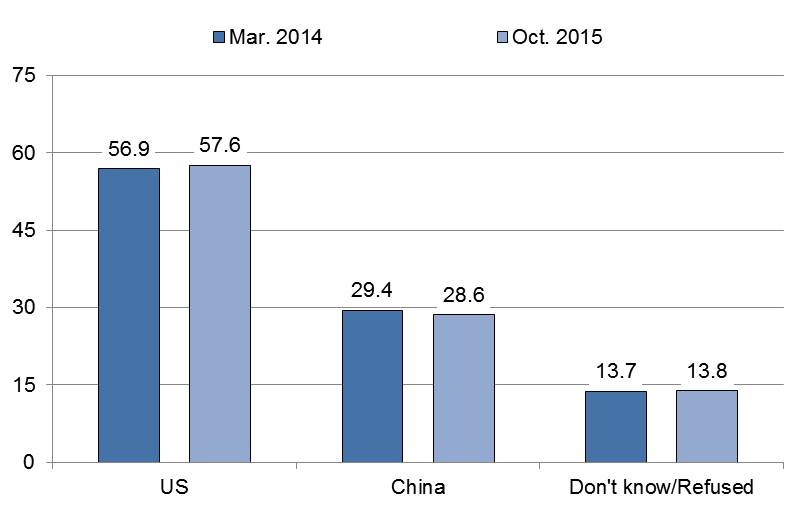

Second is that the percentage of those surveyed expressing the need for strengthening cooperation with China has consistently been half that of those individuals who support greater cooperation with the United States (Figure 5). The significant finding here is that these trends are apparent in the wake of President Park’s recent visits to Beijing and Washington.

Figure 5: Country with Which to Strengthen Cooperation14

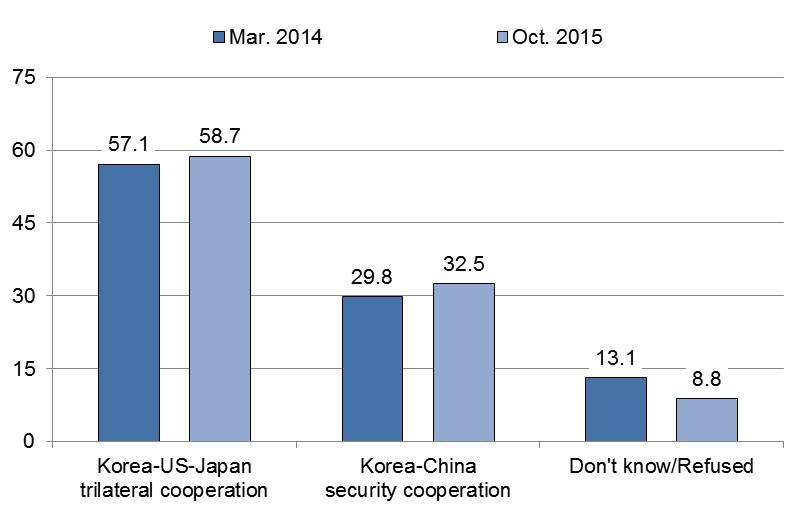

With regards to regional security, an overwhelming majority agree that it should be based on the Korea-US-Japan trilateral cooperation (58.7%) rather than the Korea-China bilateral framework (32.5%). Both figures are an increase from March 2014 (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Framework for Security Cooperation15

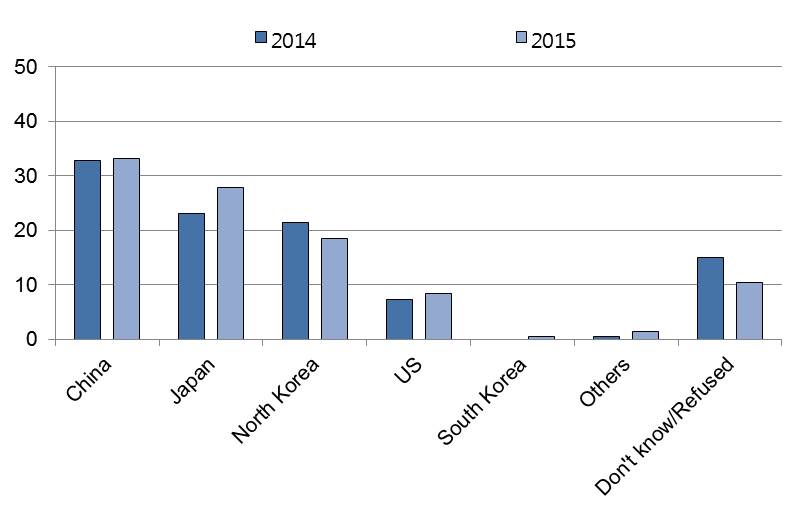

This is less than surprising given that the majority (52%) supports the Obama administration’s the Asia Re-balance and also views the necessity of the US-ROK alliance (95%) even after reunification (82%). Part of this trend may be motivated by the perception that China is seen more as a future economic and/or security threat to South Korea than any other countries in the region. It is also worth noting that this is also more likely to be the case among under-50 year olds by a factor of about 22%.

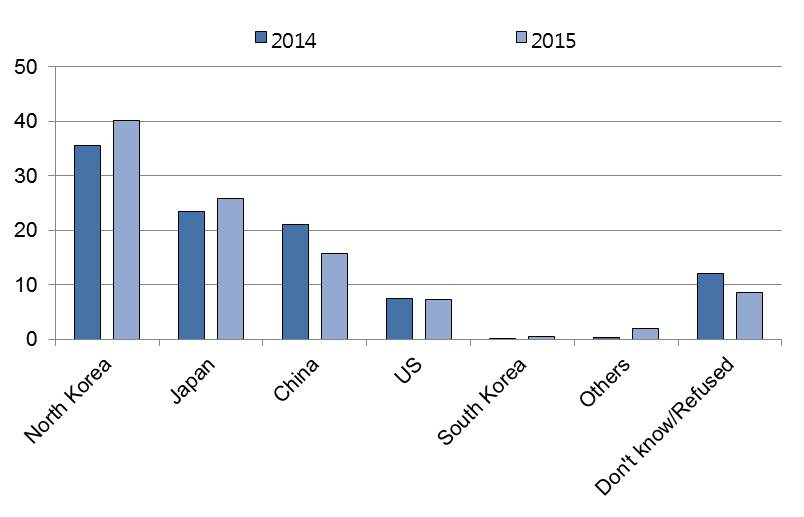

Figure 7: Perceptions about Future Threat to South Korea16

Potential Areas of Improvement

The survey results also indicate some potential areas of improvement. Taking a look at the present and future threat perception, Japan looms large as a continuing source of worry for the South Korean public (Figures 7 and 8). The threat perception has actually increased from last year and this may correspond to the recent passage of new legislation in Japan enabling the military to pursue collective self-defense. Whatever may be driving these patterns, an increase in the Korean public’s perception about the Japanese threat will remain as a significant obstacle for US foreign policy and security posture in the region given the centrality of its alliances with both South Korea and Japan.

Figure 8: Perceptions about Present Threat to South Korea17

An interesting within-sample variation is the threat perception among different age groups. Comparison of the difference in the perceived future versus present threat suggests that individuals aged 50 and older tend to view Japan as more of a future (rather than present) threat by a factor of 9.3% while those 40 and under tend to see Japan as more of a present (than future) threat by a factor of 3.3%.

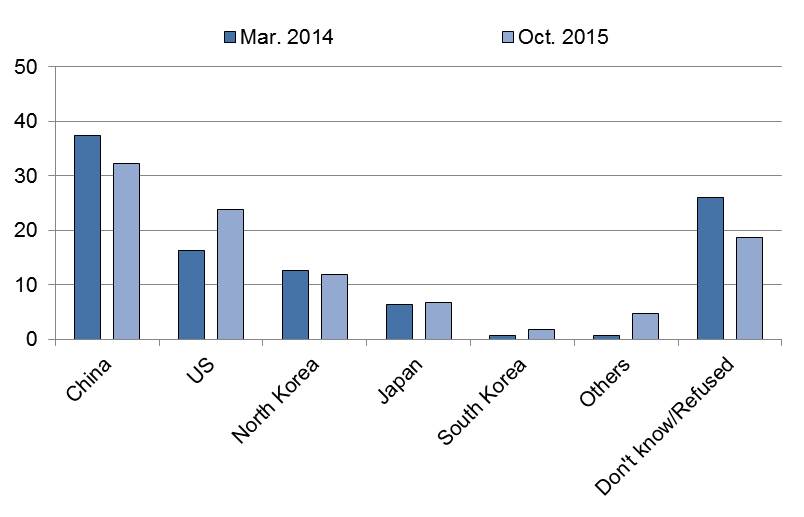

On the issue of North Korea’s nuclear problem, the plurality of those surveyed sees China as a major obstacle but an increasing number of people also see the US as a contributing factor. As we can see from Figure 9, the percentage of individuals identifying the US as an obstacle to solving the North Korean problem has increased from about 16% to 21% over the past year. While the recent Joint Statement on North Korea may have addressed some of these concerns, the fact that there has not been any significant progress on this issue suggests that the two countries must find some way to break through the impasse on the talks or get the Kim Jong-un regime to change its calculus on this issue.

Figure 9: Main Obstacle to Solving North Korea’s Nuclear Problem18

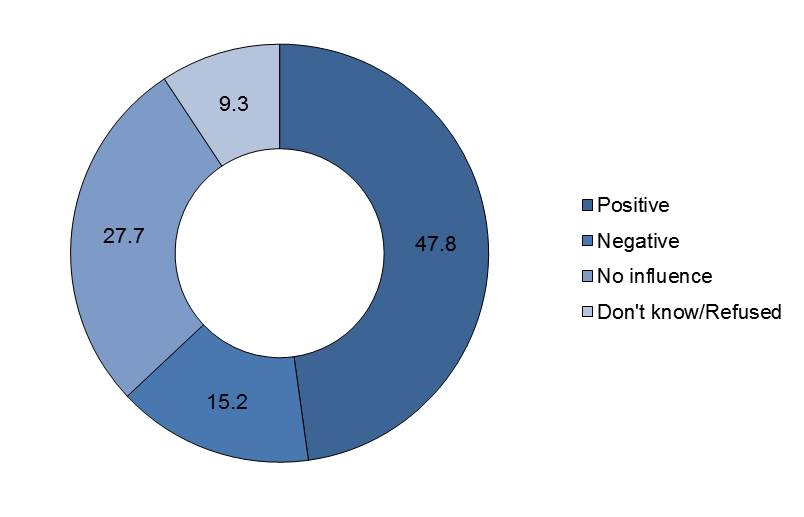

Although expert opinion is that the recent summit will not lead to major changes in North Korea’s behavior, there is hope among the public at least that there may be an improvement in inter-Korean relations (Figure 10).19

Figure 10: Influence of the Summit on inter Korean Relations20

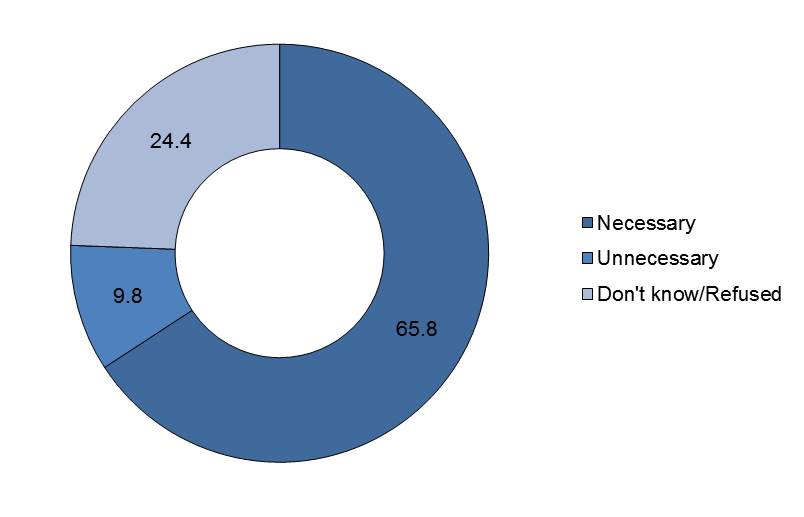

Finally, there is also strong public support for South Korea’s membership in the TPP for the time being (Figure 11). Given that South Korea has yet to finish its bilateral consultations with the inaugural members and the agreement has yet to be ratified in the respective member countries, this issue will remain as something that requires continuing dialogue in the future.

Figure 11: Opinions about South Korea’s Membership in the TPP21

Conclusion

In general, the recent Obama-Park summit can be summarized as a glass half-full or half-empty in the sense that there were notable accomplishments but no important milestones. On the one hand, the overall mood and state of the alliance are as strong as ever. The two leaders have cultivated good relations and deepened the level of cooperation among the two countries. From this standpoint, the most recent summit can be deemed a success. However, the two countries must not lose sight of the difficult challenges that remain as the backdrop of this alliance – namely the North Korean nuclear program, Korea-Japan relations, and an emboldened China. The difficulty here is that these problems are deeply rooted in the structural foundation of the region. Undoing this Gordian knot will not be easy. This explains the lack of major breakthroughs.

For the time being, the approach that both leaders seem to favor is one that seeks to sharpen the message to China that friendly engagement, while favored, must occur within the broader context of acceptable international norms and laws. With respect to North Korea, the joint statement is unequivocal: both the US and ROK are ready to support and assist North Korea’s economic development under the condition that North Korea must demonstrate a genuine willingness to abandon its nuclear and ballistic missile programs. On Japan, the US would like Japan and South Korea to find a way forward. While it is unclear what this “way” may be, one thing is certain: Prime Minister Abe’s last statement on this matter has been less than satisfactory from South Korea’s point of view. The crux of the problem lies less in what South Korea will require in order to be made whole on this issue than in the political willingness and courage of the leaders to take the necessary steps to begin the next chapter in their history.22 Finally, as the two leaders have shown, the inability to make significant progress on these age old problems does not mean that there are no areas of measurable achievements moving forward. Both countries seek to continue deepening involvement in those areas of converging interests while looking for the opportune moment to move ahead on more challenging policy problems.

Survey Methodology

Asan Poll

Sample size: 1,000 respondents over the age of 19

Margin of error: ±3.1% at the 95% confidence level

Survey method: RDD for mobile and landline telephones

Period: See report for specific dates of surveys cited

Organization: Research & Research

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 1.

The authors wish to thank Scott Snyder, Nicholas Eberstadt, Choi Kang, Peter Beck, and Robert Manning for their comments and feedbacks on earlier versions of this paper. Standard caveats apply.

- 2.

Scott A. Snyder, “A Pivotal U.S.-Korea Summit?” Council on Foreign Relations, October 13, 2015; “The U.S.-South Korea Summit Scorecard and Future Alliance,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, October 19, 2015

- 3.

Ankit Panda, “Park Geun-hye’s Visit to Washington: Major Takeaways,” The Diplomat, October 17, 2015; Julie H. Davis, “Obama and South Korean Leader Emphasize Unity,” The NY Times, October 16, 2015; Victor Cha and Andy Lim, “Previewing the Park-Obama Summit: Intimacy and Substance, not Ceremony,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, October 14, 2015.

- 4.

Edwin J. Feulner, “Nurturing a Crucial Alliance,” The Heritage Foundation, October 15, 2015

- 5.

Karl Friedhoff and Dina Smeltz, “Americans Positive on South Korea and Support to Defend It at All-time High,” The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, October 2015.

- 6.

Joint Declaration in Commemoration of the 60th Anniversary of the Alliance between the Republic of Korea and the United States of America. May 7, 2013.

- 7.

Joint Statement on Addressing Global Climate Change. May 7, 2013; 2015 United States of America and Republic of Korea Joint Statement on North Korea. October 16, 2015.

- 8.

Fact Sheet: The United States-Republic of Korea Alliance. May 7, 2013; Joint Fact Sheet: The United States-Republic of Korea Alliance: A Global Partnership. April 25, 2014; Joint Fact Sheet: The United States-Republic of Korea Alliance: Shared Values, New Frontiers. October 16, 2015.

- 9.

Note that we are not suggesting here that the substance of these meetings can be summed up with the frequency of topic or issues that are highlighted in these press conferences. But these data points do provide some comparative reference points for determining which issues received more or less attention across each meeting.

- 10.

See Appendix I for data and methodology

- 11.

Asan Poll (January 2014 – October 2015)

- 12.

Asan Poll (January 2014 – October 2015)

- 13.

Asan Poll (November 14-16, 2014; October 19-20, 2015)

- 14.

Asan Poll (March 16-18, 2014; October 19-20, 2015)

- 15.

Asan Poll (March 16-18, 2014; October 19-20, 2015)

- 16.

Asan Poll (March 7-9, 2014; October 19-20, 2015)

- 17.

Asan Poll (March 7-9, 2014; October 19-20, 2015)

- 18.

Asan Poll (March 7-9, 2015; October 19-20, 2015)

- 19.

It is not clear that the recent ROK-US summit had any role in contributing to a positive outlook on inter-Korean relations. We base this conclusion on a comparison with another survey that the Asan Institute for Policy Studies conducted during September 9~11, 2015. In this survey, we asked the respondents to state whether they thought inter-Korean relations would improve, get worse, or not change. 45.8 percent of the respondents agreed that they expected the relations to improve. 35.7 percent were pessimistic and 9.6 percent did not think that there would be major changes. Given that the figure for a favorable outlook is comparable to the 47.8% that we observed immediately after the summit, we can conclude with reasonable certainty that the summit has had little to no impact on the overall outlook about relations with North Korea.

- 20.

Asan Poll (October 19-20, 2015)

- 21.

Asan Poll (October 19-20, 2015)

- 22.

Brad Glosserman and Scott A. Snyder. 2015. The Japan-South Korea Identity Clash. New York: Columbia University Press.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter