When the five permanent members of the UN Security Council plus Germany (“P5+1”) reached a nuclear deal with Iran in November 2013, in which Iran accepted to roll back key aspects of its nuclear program in exchange for partial lifting of the sanctions, even casual observers of international affairs could see the stark contrast between the progress that the international community was able to make vis-à-vis Iran and its failure to achieve even a semblance of pressure with respect to North Korea.

There is little doubt that the comprehensive sanctions regime that exists in the case of Iran, as well as the lack thereof for North Korea, played an important role in determining the difference in the outcomes. The unequal enforcement of sanctions is even more surprising in light of the fact that the international sanctions regimes against the two countries share similar aims and governance structure, which are rooted in the decade-long effort by the international community to design and implement effective sanctions regimes against WMD proliferation.

In sum, the difference in outcomes is not due to the fact that the two sanctions regimes had different objectives and origins, but because the two regimes evolved differently from the same baseline. A major factor in explaining the divergence is the fact that Iran remained in the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) while North Korea had left it in 2003. Because Iran was bound by the treaty requirements the international community was able to build a systematic sanctions regime to punish Iran’s transgressions within the non-proliferation framework, whereas there was no obvious enforcement device to penalize North Korea for leaving the treaty (Choi 2005).

The paradox of international sanctions regime against Iran and North Korea lies with the fact that the international community’s experience with North Korea translated to better, tighter sanctions measures against Iran, but rarely vice versa. North Korea’s escalating nuclear provocations, including its third nuclear test in 2013, led to ever-increasing pressure on Iran instead. While such a course of action taken by the international community against Iran arguably strengthened the NPT regime, it also allowed a serious nuclear threat to grow unchecked outside of it.

Inconsistent efforts on the part of the international community in addressing the North Korean nuclear threat has undermined the non-proliferation process, and reduced North Korea to the role of Iran’s counterfactual: that is, North Korea became a useful illustration of what Iran would become unless the international community stopped its nuclear ambitions, rather than a serious nuclear threat in its own right. It is about time the international community amended the sanctions regime against North Korea to be in line with the actual level of threat it poses to the world.

Overview of Sanctions Regimes against Iran and North Korea

1. United Nations Security Council Resolutions

The basis for the international sanctions against Iran and North Korea is founded on the landmark UN Security Council Resolution 1540, which declared WMD proliferation to be a threat to peace under Chapter 7 of the United Nations Charter, and obliged all member countries to create a legal framework for the prosecution of proliferation activities. While resolution 1540 was principally motivated by the presence of non-state actors (i.e., Al Qaeda) intent on acquiring weapons of mass destruction, the same enforcement framework equally applied to non-state proliferators for nation states.

While UN Security Council resolutions form the basis of the international sanctions regimes, they also incorporate lessons and best practices from the member countries. The case in point is Banco Delta Asia (BDA), which demonstrated to policymakers in the international community that targeting designated individuals and entities’ access and use of financial networks could be more effective than freezing targets’ financial assets (Loeffler 2009).

In addition, one of the original aims of resolution 1540 was to create a common framework for interdiction of illicit cargoes (NTI 2013) in the spirit of Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI). This component, while absent in the final draft of resolution 1540, has been gradually incorporated into subsequent UN resolutions. As a result, the UN sanctions measures came to include two major elements of interdiction and financial sanctions, which essentially wrapped all major non-proliferation initiatives (Non-Proliferation Treaty, Chemical Weapons Convention, etc.) together with global interdiction efforts (i.e., PSI) in a single framework under Chapter 7 of the UN Charter.

However, while the international community finally succeeded in formulating an effective non-proliferation framework, its application was hamstrung by differential enforcement of the sanction measures. Even a superficial lookover of the UN resolutions for North Korea and Iran reveals that the sanctions against Iran were methodically increased almost on an annual basis, and closely tracked Iran’s continued failure to comply with IAEA demands. No such matching between sanctions measures and progress (or lack thereof) in denuclearization is shown in the resolutions against North Korea. Unfortunately, this pattern of differential treatment is to be found with the other two major sanctions regimes as well, shown subsequently in the next section.

2. US Sanctions against Iran and North Korea

The underlying basis of the US sanctions regime is a set of financial restrictions and sanctions applied against individuals and entities that abet WMD proliferation. The Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) under the Treasury Department complements the provisions outlined in the Executive Orders of the President of the United States and maintains a list of designated individuals and entities. While the US prioritizes multilateral cooperation with other states and international bodies, it often augments the UN sanctions measures with its own, in order to put them in line with US national security policy.

As a result, the United States tends to take unilateral sanctions measures more liberally than other states and international bodies. In fact, it was the United States that identified Iran’s energy industry as its weak spot and banned investment in Iran’s oil sector through the Iran & Libya Sanctions Act of 1996. The act was controversial for its extraterritorial provisions, which would also figure in the unilateral sanctions against Iran two decades later. Theoretically, the US government could sanction non-US as well as US firms that invested in Iran’s oil sector, but in practice the US government issued waivers for non-US firms investing in Iran to avoid diplomatic backlash from its allies.

As illustrated in the above example, extraterritorial measures and secondary boycotts have long been part of US coercive diplomatic strategy, but the United States was not able to implement them to the full extent due to the controversy surrounding its legal jurisdiction. However, once the diplomatic mood was finally ripe, these types of unilateral measures, such as the Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability and Divestment Act of 2010 (CISADA)1, were successfully implemented starting in 2010.

It should be noted, however, that these unilateral measures only applied to Iran. In the case of North Korea the United States limited the scope of the restrictive measures to proliferation activities only, and even then, these were issued after similar measures had already been put in place against Iran. A good example is the Iran Nonproliferation Act of 2000, the North Korean equivalent of which only came into place in 2006. In sum, the two sanctions regimes have very significant differences in terms of breadth and depth.

3. European Union Sanctions against Iran and North Korea

The European Union maintains a bilateral agreement with the United Nations that obliges it to implement UN Security Council resolutions. In addition, the Treaty on European Union gives the Council of the EU discretion to implement sanctions measures in accordance with the EU Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). For a long time the EU position towards taking punitive actions against Iran and North Korea was closely bound to the scope determined by UN resolutions. These were implemented by the individual member states first, followed by EU-wide measures shortly after.

The adoption of CFSP goals to prevent Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons, however, turned the process on its head. Instead of waiting for the UN to take action, the EU assumed a more proactive role in the process, which even resulted in accusations that the EU had overstepped its jurisdictional boundaries (Esfandiary 2013). Using its clout in the international trade and financial networks, as well as the fact that Iran had long relied on Europe for trade and financial services, the EU adopted restrictive measures that greatly impacted Iran’s ability to finance its nuclear program. Council Decision 2010/413 not only targeted individuals and entities engaged in proliferation activities, but like UNSCR 1929 it included the Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines (IRISL) that targeted Iran’s transportation sector. The Council Regulation No 267/2012 went further, by banning European insurance firms from providing coverage to Iranian shipping, as well as excluding Iranian financial institutions from SWIFT interbank settlement networks. Most importantly, the EU orchestrated a successful embargo on Iran’s oil exports, the revenues of which finance much of the government budget. Partly as the result of EU’s initiative, other countries, most notably South Korea and Japan, also joined the oil embargo against Iran.

By contrast, EU sanctions against North Korea have never overreached the boundaries set by the UN resolutions. This state of affairs extended to the realm of human rights records as well. The European Union has extensive provisions for sanctioning Iranian authorities suspected of being involved in human rights violations. A case in point is Council Regulation No 359/2011, which instituted embargoes on telecommunication and enforcement equipment that could be used for internal repression, in addition to designating individuals and entities involved in such activities. No such EU measures are in place in regard to North Korea’s human rights situation, despite the fact that North Korea’s records are possibly far worse than Iran’s.

How to Quantify and Compare Sanctions Regimes?

The patterns of differential treatment of Iran and North Korea are not only qualitative, but quantitative as well. Sanctions are essentially legal measures that define the scope and depth of the restrictions on the targeted activities. Because of their semantic nature, sanctions are not easy to quantify for comparative analysis. Yet there is a major numerical component to the sanctions regime, which is the list of individuals and entities targeted by the restrictive measures.

One can argue that the strength of a sanctions regime is correlated with the length of the list of designated individuals and entities. While the comprehensiveness of the target list does not necessarily indicate the effectiveness of sanctions implementation, it nonetheless is indicative of the intensity of the sanctions.

Yet there are important caveats when it comes to actual comparative analysis. First, one should not use the absolute size of the designated list to compare sanctions regimes corresponding to different countries. Two factors come into play in determining the size of the list. One is the number of individuals and entities involved in the restricted activities, i.e. targets, and the other is the range of economic and financial activities that the sanctioned country is engaged in. The latter is very important to take into account especially when it comes to comparing Iran and North Korea, which are very differently structured in terms of both their domestic economies and their roles in international trade. In the case of Iran, despite its unique theocratic political system, its economy and the government’s revenues rely heavily on energy exports. Iran also welcomes foreign investment and its citizens travel abroad relatively freely. North Korea could not be more different: its total external trade is puny at USD6 billion as of 2012 (IIT 2013), travel is restricted, and it is one of the poorest countries in the world. It is only natural that Iran would offer more “targetable” individuals and entities to the architects of international sanctions regimes compared to North Korea. As a result, relying on the absolute number of designated individuals and entities to compare the intensity level of sanctions regimes could actually be misleading. The length of the list would only indicate the relative availability of the targets rather than the actual level of sanctions enforcement.

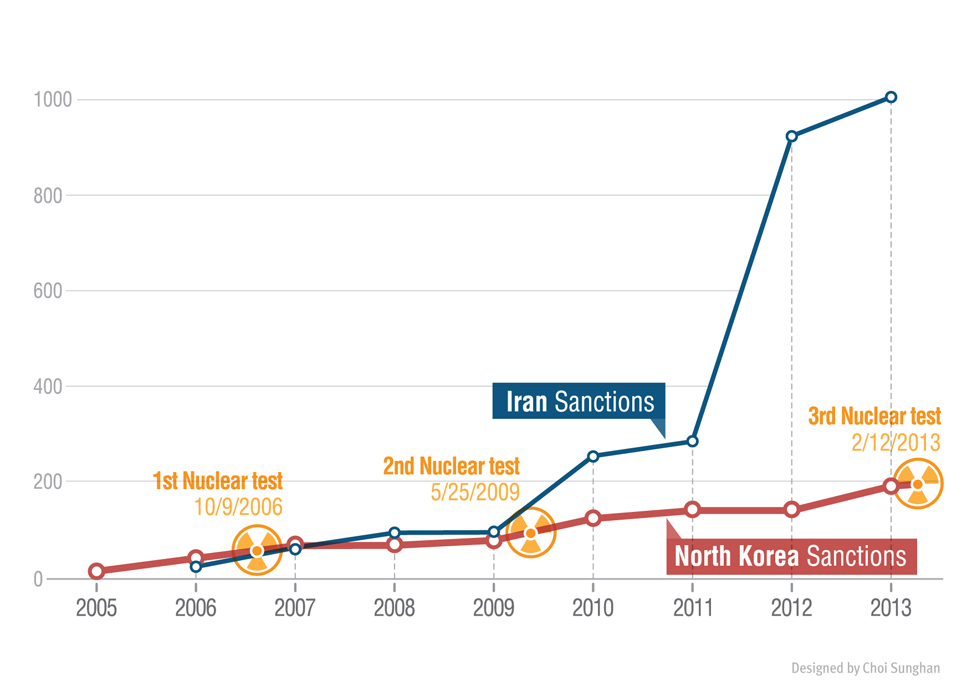

If the lists are not directly comparable, how can one draw meaningful inferences from this data? One salient feature of the lists of sanctioned individuals and entities is the fact that these lists evolved over time and consequently differentiable time trends became apparent. Figure 1 shows that the number of sanctioned individuals and entities for each sanctions regime accumulated in similar fashion since their simultaneous inception in 2006, but have diverged radically beginning in 2010. The “inflection point” denotes a significant change in the accumulation trends of individuals and entities listed in Iran and North Korea sanctions after North Korea conducted its second nuclear test: while the number of individuals and entities in the Iran sanctions increase almost geometrically after that point in time, the corresponding quantity for North Korea, despite the fact that it was one that crossed “the red line”, did not increase.

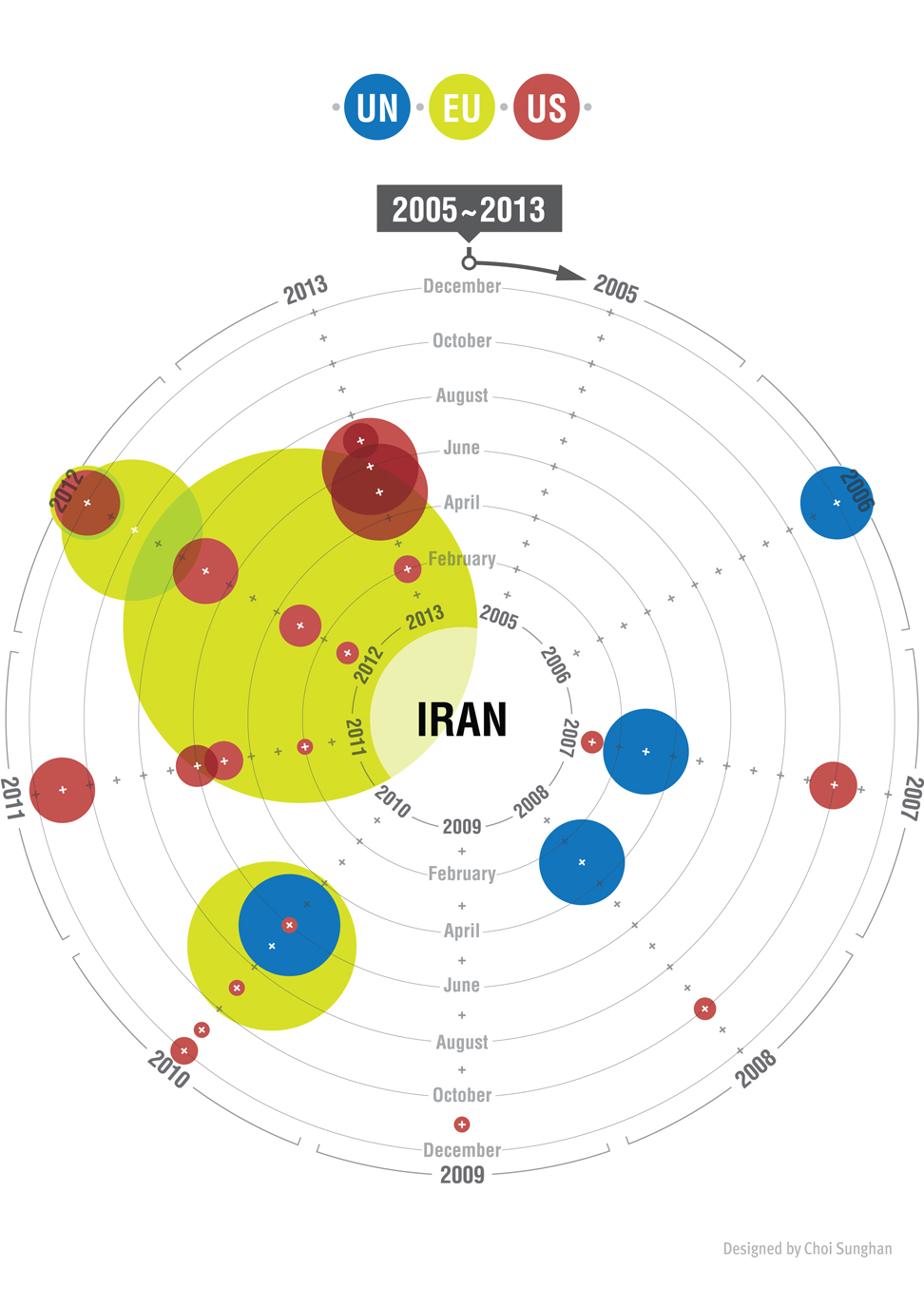

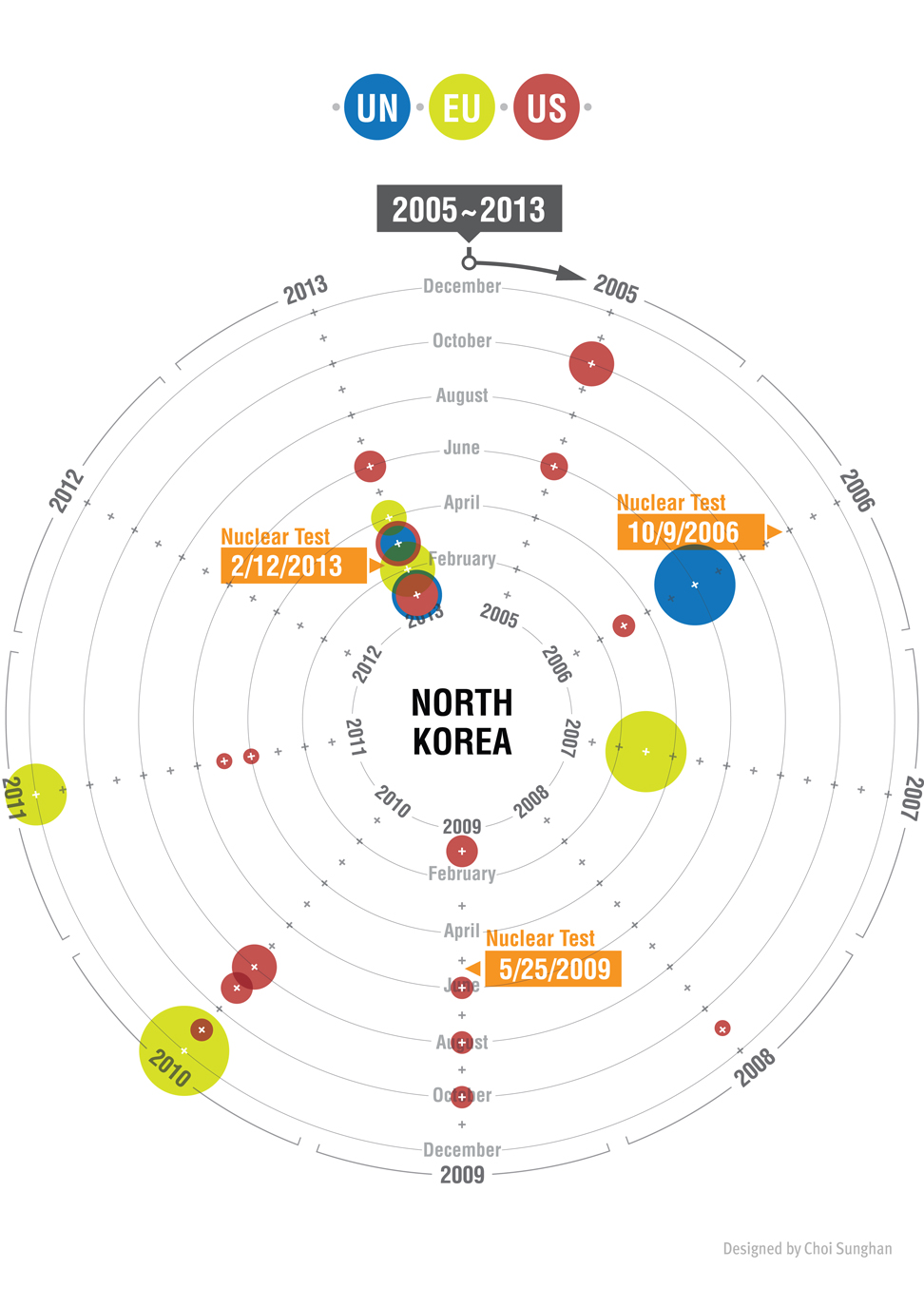

Figure 2 and 3 show what could be underneath this difference: While North Korea and Iran sanctions regimes were both founded on a series of non-proliferation UN Security Council resolutions with the specific aim of stopping WMD proliferation, the two sanctions regimes diverged significantly when the European Union and the United States imposed unilateral sanctions on Iran. It is apparent that after 2010, the EU took charge of the sanctions initiative for both Iran and North Korea. The relative sizes of circles, which represent the number of individuals and entities added with each new sanctions measure, show that the EU escalated its sanctions campaign against Iran much more rapidly and frequently from 2010.

Conclusion

The intensity of these unilateral sanctions on the part of the EU and the US reflected the latters’ preference for stronger measures than the ones found in the UN resolutions, which have to be agreed on by all five permanent members of Security Council. The US and the EU, which consider themselves to be potential targets of Iran’s nuclear weapons, had stronger incentives and sense of urgency than Russia and China, which led them to formulate a more comprehensive sanctions regime that complemented the already stringent measures taken by the UN against Iran.

Given the technical similarities between Iran and North Korea’s nuclear programs2, the shared reliance on AQ Khan’s proliferation and nuclear supply networks, antecedents of sponsoring terrorism, and anti-Americanism deeply ensconced in both regimes, there is no doubt that Iran and North Korea are similar in terms of the potential threat that they pose to the international community. But there are fundamental differences that we cannot ignore. North Korea, unlike Iran, has tested the weapon three times and it is clearly in possession of weapons-grade enriched uranium and plutonium. Iran is yet to accumulate sufficient levels of enriched uranium, let alone conduct a nuclear test. The Iranian government, no matter how inadequate, has a democratically elected president. North Korea has the Kim Dynasty.

Yet, as this study shows, the international response to the two countries’ nuclear programs could not have been more different. The sanctions regime against Iran is characterized by the steady application of ever-increasing pressure to force Iran to give up its nuclear program. In terms of international policy coordination, the US and the EU worked relentlessly to overcome the reluctance of China and Russia over extending sanctions against Iran (Lim and Moon 2013). Such efforts are missing in the case of North Korea. Moreover, the sanctions regime against North Korea is still restricted in scope and not commensurate with the real level of threat it poses to the rest of the world. The international community might have gone a long way with regard to Iran’s nuclear program by treating North Korea as Iran’s counterfactual, but it might have done too little, too late for North Korea itself.

Appendix: UN, US, and EU sanctions measures

| Adoption Dates | North Korea | Note | Iran | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006.7 | UNSCR 1696 | Calls for suspension of the uranium enrichment program and compliance with IAEA rulesSanctions: None | ||

| 2006.10 | UNSCR 1718 | Condemns North Korea for conducting nuclear test and prohibits further tests. Calls for suspension of ballistic and nuclear weapons programsSanctions: export ban on nuclear related goods and luxury goods. Calls for cargo inspection. Travel ban and asset freeze against individuals and entities associated with proliferation activities | ||

| 2006.12 | UNSCR 1737 | Requires Iran to suspend its uranium enrichment program and ratify IAEA’s Additional ProtocolsSanctions: export ban of ballistic and nuclear related goods.Travel ban and financial sanctions (freeze of assets) against individuals and entities associated with proliferation activities | ||

| 2007.3 | UNSCR 1747 | Cites Iran for failing to comply with UN demands Sanctions: expanded list of individuals and entities. Strengthening of existing sanction measures. Ban on lending financial services to the Iranian government |

||

| 2008.3 | UNSCR 1803 | Cites Iran for failing to comply with UN demands Sanctions: expanded list of individuals and entities. Strengthening of existing sanctions. Ban on trade-related financial services. Transportation restrictions |

||

| 2009.6 | UNSCR 1874 | Condemns North Korea for conducting its second nuclear test. Calls for its return to the six party talks and the NPT Sanctions: expanded list of individuals and entities. Ban on the provision of financial services to North Korea. Requires cargo inspection |

||

| 2010.6 | UNSCR 1929 | Cites Iran for failing to comply with UN demands Sanctions: expanded list of individuals and entities. Strengthening of existing sanctions. Financial sanctions that specifically target IRISL3 and the IRGC4 |

||

| 2013.1 | UNSCR 2087 | Condemns North Korea for ballistic missile test in violation of previous UNSCRsSanctions: strengthened existing sanctions and inspection regime | ||

| 2013.3 | UNSCR 2094 | Condemns North Korea for conducting its third nuclear test in violation of previous UNSCRs. Sanctions: in addition to strengthening existing measures, implemented enhanced financial sanctions. Prohibited bulk cash transfers and the use of international financial networks. |

| Iran | North Korea |

|---|---|

| Iran-Iraq Arms Nonproliferation Act of 1992Iran & Libya Sanctions Act of 1996Iran Nonproliferation Act of 2000Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability and Divestment Act of 2010 (CISADA)Iran, North Korea, Syria Sanctions Consolidation Act (May 2011)Iran Threat Reduction Act (August 2012)The Iran Freedom and Counter-Proliferation Act of 2012 (IFCA) | North Korea Non-Proliferation Act (July 2006)Iran, North Korea, Syria Sanctions Consolidation Act (May 2011) |

| Iran | North Korea |

|---|---|

| Council Decision 2010/413/CFSP5Amended or implemented by:Council Decision 2010/644/CFSPCouncil Decision 2011/299/CFSPCouncil Decision 2011/783/CFSPCouncil Decision 2012/35/CFSPCouncil Decision 2012/152/CFSPCouncil Decision 2012/169/CFSPCouncil Decision 2012/205/CFSPCouncil Decision 2012/457/CFSPCouncil Decision 2012/635/CFSP Council Decision 2012/687/CFSPCouncil Decision 2012/829/CFSPCouncil Decision 2013/270/CFSPCouncil Decision 2013/497/CFSPCouncil Decision 2013/661/CFSPCouncil Decision 2013/685/CFSPCouncil Decision 2014/21/CSFP |

Council Regulation (EC) No 329/2007Amended or implemented by:Commission Regulation (EC) No 117/2008Council Regulation (EU) No 1283/2009Council Regulation (EU) No 567/2010Commission Implementing Regulation (EU)Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 137/2013Council Regulation (EU) No 296/2013Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 370/2013Council Regulation (EU) No 517/2013Council Regulation (EU) No 696/2013 |

| Council Regulation (EU) No 267/2012Amended or implemented by:Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 350/2012Council Regulation (EU) No 708/2012Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 709/2012Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 945/2012Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 1016/2012Council Regulation (EU) No 1067/2012Council Regulation (EU) No 1263/2012Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 1264/2012Council Regulation (EU) No 517/2013Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 522/2013Council Regulation (EU) No 971/2013Council Regulation (EU) No 1154/2013Council Regulation (EU) No 1203/2013 Council Regulation (EU) No 1361/2013Council Regulation (EU) 42/2014 | Council Decision 2013/183/CFSP |

Figure 1. The cumulative number of individuals and entities listed in sanctions regimes

Figure 2. The number of individuals and entities listed in North Korea’s sanctions regimes

Figure 3. The number of individuals and entities listed in Iran’s sanctions regimes

References

-

Arms Control Association. UN Security Council Resolutions on North Korea. Updated March 2013. <http://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/UN-Security-Council-Resolutions-on-North-Korea>

-

Arms Control Association. UN Security Council Resolutions on Iran Updated August 2012. <http://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/Security-Council-Resolutions-on-Iran>

-

Choi K. (2005). The US strategy against WMD threat: Iran and North Korea cases(Korean). Major International Issues Analysis. Institute of Foreign Affairs and National Security.

-

Esfandiary D. (2013). Assessing the European Union’s sanctions policy: Iran as a case study. Non-Proliferation Papers No. 34. EU Non-Proliferation Consortium.

-

European Commission. European Union restrictive measures (sanctions) in force. Updated 31 July 2013. <http://eeas.europa.eu/cfsp/sanctions/docs/measures_en.pdf>

-

Institute for International Trade. (2013). 2012 trends in North Korea-South Korea and North Korea-China trades (Korean). Korea International Trade Association (KITA).

-

Lim KS., Moon DH. (2013). Politics in the UN Security Council Sanctions (Korean). Paju. Hanul Academy.

-

Loeffler RL. (2009) Bank Shots: How The Financial System Can Isolate Rogues. Foreign Affairs March/April 2009.

-

Nuclear Threat Initiative. UNSCR 1540 Resource Collection. Updated 21 October 2013. <http://www.nti.org/analysis/reports/1540-reporting-overview/>

-

Office of Foreign Assets Control, the US Treasury Department. Specially Designated Nationals List. <http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/SDN-List/Pages/default.aspx>

-

Wertz D., Vaez A. (2012). Sanctions and Nonproliferation in North Korea and Iran: a Comparative Analysis. Federation of American Scientists.

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 1

CISADA allows the US to sanction any financial institution that provides services to Iranian banks, including those outside its jurisdiction.

- 2

Both countries took the same approach towards achieving nuclear capability by producing weapons-grade Highly Enriched Uranium (HEU) using centrifuge plants.

- 3

Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines.

- 4

Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps.

- 5

CFSP: Common Foreign and Security Policy of the European Union

| The author would like to thank Choi Sunghan for the design of information graphics and Sung Jiyoung for her research assistance. |

|---|

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter