Executive Summary

North Korea’s New Five Plan contained in the 8th Party Congress work report paints a picture of a regime that hunkering down for the long run. The future direction of the economy as outlined in the new five-year economic plan doesn’t offer radical solutions, but instead it points towards economic retrenchment. This will cause more economic hardship, but it will also lessen the economy’s dependence on foreign trade, thereby blunting the impact of sanctions.

The combination of economic retrenchment and growing nuclear capability raises the prospect of an intransigent North Korea when it comes to denuclearization. Economic retrenchment should not be interpreted as an indicator of regime’s desperation, but as an active response by the regime to stabilize the economy. To further ensure internal stability, the regime will intensify propaganda campaigns and cult of personality around Kim Jong Un.

In the meantime, North Korea will continue with its strategy of mass production of nuclear weapons. By amassing more powerful and longer-range nuclear weapons, North Korea will demonstrate to the United States that it is futile to pressure it to denuclearize completely. While in the short run Kim is willing to wait for the Biden administration to take the first step towards dialogue, if such an overture doesn’t materialize soon the regime is likely to embark on a new cycle of tensions until the United States acknowledges North Korea as a de factor nuclear state.

Introduction

The highlight of the 8th Party Congress that took place last January was Kim Jong Un’s opening remark, in which he earnestly acknowledged the failure of the economic plan that he had proposed five years earlier in the 7th Party Congress1. Kim’s speech surprisingly apportioned more blame on internal policy failures than the obvious external factors of sanctions and global pandemic. Such earnestness could simply be a ploy to justify personnel reshufflings (i.e., purges) that would inevitably ensue after the supreme leader’s acknowledgement of grave policy failures. Yet the new policy measures enacted (and not enacted) show that the regime is gearing up for a long period of isolation and pressure by the United States.

While North Korea does not produce white papers that offer insights into the regime’s future policy directions, the 8th Party Congress work report published in Rodong Sinmun2 perhaps comes closest. Although much of the report consists of old ideological discourses rehashed from the last Party Congress in 2016, Party editors, conscious of the fact that the work report serves as policy directives to the Party members as well as strategic communication to the outside world, have mixed actual policy measures with messages directed at South Korea and the United States. In order to separate meaningful information from fluff, this study compares the work report with the proceedings of the 7th Party Congress in 2016.

The comparison of the two texts shows that the regime has placed special emphasis on the new five-year economic plan and the expansion of nuclear capability, which were accorded generous amounts of space at the expense of political and ideological discourses. Generous details contained in the nuclear capability section were clearly intended to rattle South Korea and the United States: the message is North Korea may hold back from provocations so long as South Korea and the United States continue the de facto suspension of joint military exercises3, with further incentive for South Korea in the form of resumption of inter-Korean dialogue down the road if it complies.

The new five-year plan provides hints about what North Korea’s intentions are for the near future. The new plan vows to bring back centralization and planning, which are clear signs that the regime is rolling back the pseudo-marketization that had achieved macroeconomic stability and economic growth in the last ten years. The return to central planning and self-reliance is tantamount to giving up the economic gains and the attendant increase in the living standards of North Koreans. But such a move would also allow the regime to control the trade deficit that is damaging the economy.

Remarkably, even the regime doesn’t seem to believe that planning and self-reliance will be effective replacements for the previous market friendly policies. The new five-year plan sets eminently attainable production goals, perhaps too much so4. The plan envisions supplying just 75,000 housing units in the next five years in just two locations. The main purpose of the new five-year plan is therefore not to supplant or fix the broken economic model, but to signal to the public the advent of economic austerity. It’s a plan for retrenchment, not development.

In lieu of economic development, the North Korean people will have to content themselves with their leader’s well-meaning words. Perhaps to deflect the blame for economic failures, the regime’s propaganda around Kim has intensified in 2020. But the cult of personality comes with a new twist: the regime is trying to project an image of Kim as the man of the people, by calling Kim’s governing philosophy “People First-ism”. Nuclear development is the only successful legacy of Kim’s vaunted “Byungjin” policy of dual pursuit of nuclear and economic developments. In order to save the façade of his signature policy, Kim is attempting to imbue himself and his new austerity policy with historic legitimacy by linking his “People First-ism” with his grandfather’s governing philosophy of “Serving the People is Serving the Heaven” (이민위천). Whether the ordinary North Koreans would be satisfied with slogans instead of bread remains to be seen.

The New Five-Year Plan

The new five-year plan represents a return to the planning policies of Kim Il-Sung and Kim Jong-Il periods and rapid rollback of limited marketization measures. Key phrases that imply managerial autonomy of state enterprises and friendly trade policies (“maintain credibility in foreign trade) inserted in the previous plan have been replaced by expressions that denote more centralization and planning. This is especially noteworthy given that the new five-year plan now contradicts the amendments made to the North Korean constitution in 2019, in which corporate managerial autonomy known as the “Socialist Enterprise Responsible Management System” and the responsible management of foreign trade were formally adopted. Given the supremacy of the party over state in North Korea, this discrepancy is likely to be resolved in another round of constitutional amendments in the near future.

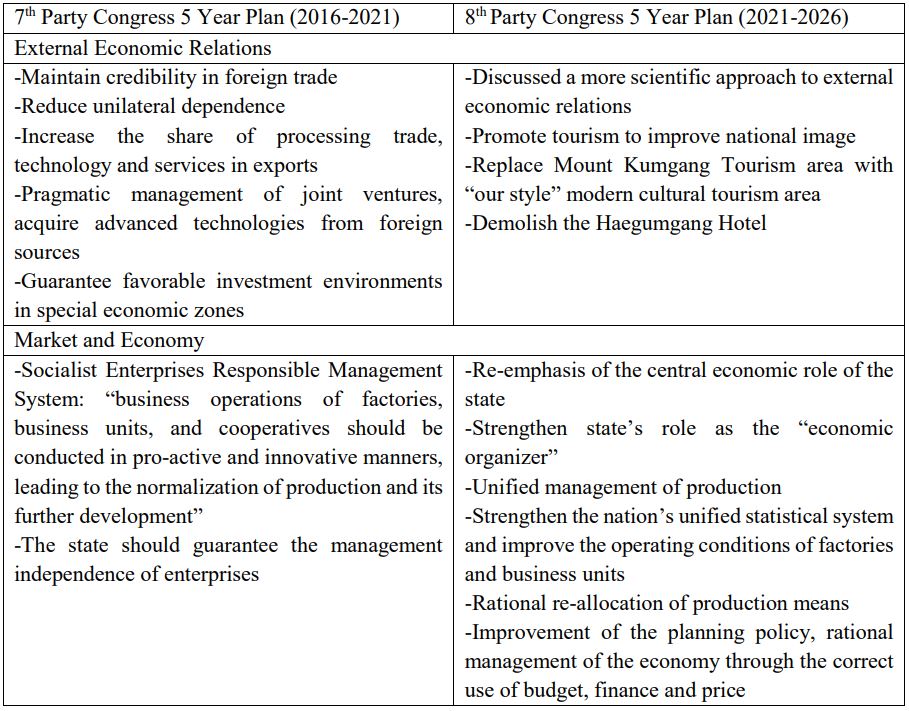

Table 1. Changes in Economic Measures:

The 8th Party Congress explicitly defined the character of the North Korean economy to be “an economy of self-reliance and planning that is at the service of the people”. This characterization is followed by the listing of new economic measures (Table 1) that strengthen the supreme role of the state as an active “organizer” of the economy, such as the proposal to improve the national statistical system and “rationally” re-allocate production means. More importantly, it also implies that the state will now intervene more actively in the real economy and financial markets by manipulating prices, as implied by the “rational management of the economy through the correct use of budget, finance and price”.

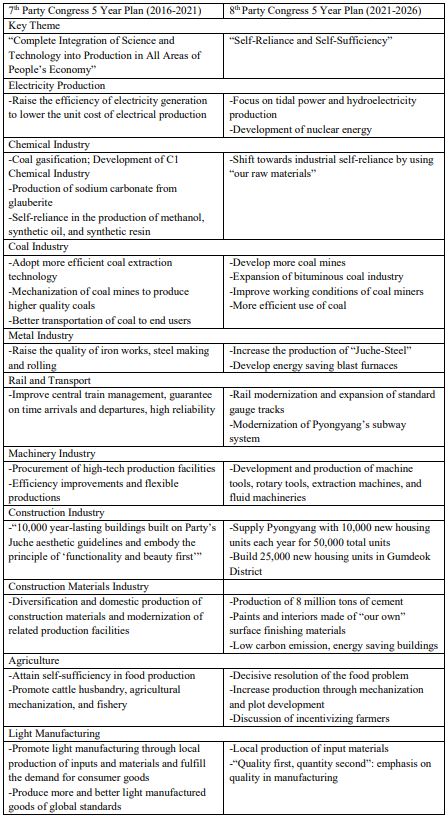

For other areas of the economy (see Appendix), such as chemical, metallurgical, and manufacturing industries, heavy emphasis is placed on the use of indigenous technology. Yet these are more reflective of the regime’s wishes than actual attainable goals. The emphasis on self-reliance is as old as the regime itself, which is particularly true in industrial sectors. North Korea also has a long history of relying on esoteric and unproven technologies such as Vinylon5, “Juche-steel”6, and coal gasification. These technologies use intermediate inputs derived from anthracite coal, which is plentiful in North Korea, in order to substitute for ethylene, coking coal, and crude oil, all of which are imported. All these indigenous technologies are celebrated by the regime as the paragons of Juche technology and industry, but have little economic value beside propaganda.

The regime is surely aware of the sorry history of Juche innovations” and unlikely to rely on them for real economic progress. In fact, the regime had implicitly abandoned them in the five-plan announced in the 7th Party Congress, in which it had declared that North Korea would acquire advanced technologies from foreign sources. The fact that the regime is bringing indigenous technology back to fore is due to the dearth of alternatives: the economic stability of the past decade relied on the steady inflow of foreign currency generated by the expansion in trade.

With the foreign currency income having evaporated due to sanctions and COVID-19, North Korea can no longer rely on the economic model of the past decade. With no viable alternative in sight, the regime is returning to self-reliance and planning because it has no other choice. Import substitution and central planning policies are not meant to propel economic growth, but rather to extract more efficiency from the economy through planning and reduce the hard currency outflow.

As for the agriculture and mining industries, the renewed emphasis on self-reliance is not new. They have long been two of the most important sectors in the North Korean economy, which represented 21.2% and 11% of the GDP7 in 2019. North Korea claims to have achieved national food independence and mining is perhaps the most competitive export sector in the country. As the result, the goals assigned to these sectors are mainly about expanding production by incentivizing miners and farmers (see Appendix).

Import substitution is more pressing in manufacturing and construction sectors, representing 18.9% and 9.7% of North Korea’s GDP7, respectively. Sanctions have deprived North Korea’s manufacturing sector of access to foreign machinery and technology, which is likely hindering the military modernization drive that the regime is pursuing. The urgent demand for import substitution is reflected in the language of the work report, which lists “rotary tools, extraction machines, and fluid machineries” as machine tools that require rapid domestic substitution.

The construction sector has long been the focus of Kim Jong Un’s attention as massive public projects such as the Masikryong ski resort, water and amusement parks in Pyongyang, and the new passenger terminal in Sunan airport, are the key differentiators that have distinguished Kim’s regime from his predecessors’. But now the goals of the construction industry have shifted from the emphasis on the Juche aesthetics of “functionality and beauty” in design and construction to pragmatic projects such as residential housing that cater to the essential needs of the North Korean public.

According to the work report, the regime will supply Pyongyang with 10,000 new housing units per year for a total of 50,000 units in the five-year period. Additionally, it will build 25,000 new housing units in Gumdeok, a mining town that was devastated by natural disasters in the past year8. The housing construction projects showcased in the work report, which will be read and studied by the Party members and general public, exemplify the goal of the new five-year plan that are meant to strengthen the role of the state not only as the central planner but also a provider that “serves the people”.

This “humbling” of Kim’s economic ambitions is manifested by the omission of the Wonsan-Kalma Coastal Tourism Zone, a veritable white elephant project that cost the regime upward of USD $580 million9 that is yet to be completed. Without acknowledging the infeasibility of tourism projects under the current climate, North Korea used the section on tourism in the five-year plan to threaten to dismantle the South Korea-built Mount Kumgang Tourism area and replace it with yet another tourism project, which given the failure of the Wonsan-Kalma project sounds hollow.

The new five-year plan represents a significant downgrading of Kim’s economic ambitions, as well as tacit acknowledgement of his country’s economic problems. But with a retrenched economy the regime can lessen the economy’s dependence on foreign trade. Kim is also signaling that he will stop frivolous construction projects meant to brush up his reputation, saving some precious economic resources. North Koreans may no longer be able to enjoy imported consumer goods, but Kim Jong Un is promising to finally commit state resources to catering some of the chronic needs of the North Korean society.

Foreign Relations

Table 2. Changes in Foreign Policy

The foreign policy section in the 8th Party Congress work report sent a clear message to South Korea and the United States in terms of what North Korean expectations are. While the message to the United States hinges upon its abandonment of “hostile attitude” towards North Korea, a vague proposition that is open to interpretation, the message to South Korea is unambiguous and specific. Pyongyang wants Seoul not to hold the annual joint military exercises with the United States and suspend the procurement of hi-tech weaponry. At the same, it dashed the current South Korean government’s hope for dialogue by categorically rejecting the South’s engagement initiatives such as public health cooperation and individual tourism. Yet, by reminding the South that the return of the “springtime” in inter-Korean relations is still possible, it strongly hinted that if South Korea didn’t resume the joint military exercises10, it could lead to the restart of inter-Korean dialogue. President Moon, who wants to finish his tenure with a high note on inter-Korean relations, is likely to interpret this as an invitation rather than a rejection of his overtures.

North Korea’s focus on the joint military exercise clearly signals that further progress in dialogue hinges upon its continued suspension. The joint nature of these exercises imply that North Korea’s demand is not only directed at Seoul, but also Washington. The lack of message to the United States paradoxically indicates restraint on the part of North Korea. The work report makes no mention of the new Biden administration, and the statements in the report regarding the United States are simply reiterations of old clichés about North Korea’s archenemy. The Trump-Kim summits are celebrated as “extraordinary” and credit is given to Kim for their realization, but the work report makes it clear that the regime harbors no hope of furthering those unprecedented diplomatic achievements, by declaring the US hostile policy towards North Korea would not change regardless of who is charge in Washington.

But North Korea leaves a sliver of hope for dialogue with the United States as well. The lack of specificity in its claims about the United States is meant to signal North Korea will withhold its judgment on the Biden administration until the latter formalizes its stance on North Korea. But Kim surely understands the prospect of a successful nuclear negotiation is even less likely with Biden. Therefore this “wait and see” attitude is less about self-restraint and more about creating the justifications for the inevitable provocations that will take place in due time.

The direction of North Korea’s future foreign policy is also outlined in the report, which implies a very close alignment with China. Compared to the intentional omission of China in the 7th Party Congress, which took place when the Sino-DPRK relation was at its rock bottom, the rapid rapprochement between China and North Korea that has since taken place is evident in the current iteration, as the regime describes Sino-DPRK relations in almost metaphysical terms (“fate”). The emphasis on common ideology with China conveniently parallels South Korea’s alliance with the United States, which alludes to possible evolution of the relationship from an informal security and economic compact to a multifaced cooperative framework. This clearly shows where North Korea’s future foreign policy is headed in the medium term: a closer alignment with China and other former and current socialist countries rather than investing in diplomatic breakthroughs with the United States or South Korea.

Nuclear Development

The 8th Party congress work report includes generous amount of information regarding the development roadmap of North Korea’s weapons systems. Most of the systems that the report mentions as having been fully developed and tested have previously been disclosed by the regime and confirmed by the ROK and US militaries.

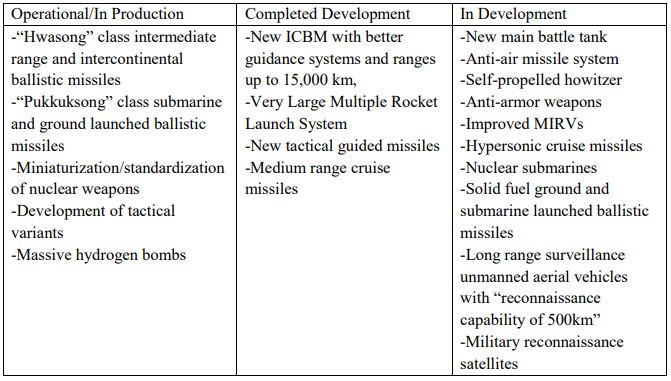

Table 3. North Korea’s new weapons systems as reported in the 8th Party Congress work report

North Korea’s intention behind revealing a plethora of new weapons systems, some of which are clearly beyond North Korea’s current technological capabilities, is meant to communicate North Korea’s strategic intentions to its main opponents, South Korea and the United States. This is most evident by examining the list of weapon systems disclosed in the report. Table 3 shows that the weapons listed in the report can be categorized into three groups: 1) weapon systems that have been deployed and are operational 2) completed development but yet to be deployed, and 3) systems that are currently in development.

The fact North Korea revealed that it is developing new cutting-edge weaponry that otherwise would be kept secret is no accident. It is meant to communicate to the outside world that North Korea’s bargaining power will increase commensurate with its future capability. It is evident from the report that North Korea intends to sharpen its delivery capability with improved MIRVs, hypersonic cruise missiles, and solid fuel ground and submarine launched ballistic missiles. In addition, nuclear submarines will strengthen North Korea’s second-strike capability. While this indicates that North Korea’s nuclear capable missiles will become more threatening and lethal, it also confirms that North Korea is yet to acquire these capabilities.

This apparent “admission” achieves two objectives: first, it paradoxically strengthens the credibility of existing North Korean claims that it has achieved sufficiently advanced nuclear capability in the form of ICBMs with 15,000 km range, miniaturized warheads, and tactical nuclear weapons. Second, by leaving some gap between present and an unspecified time in the future when these weapons currently in development become fully operational, North Korea is tempting the international community to entreat North Korea diplomatically before “it is too late”. Long range reconnaissance unmanned aerial vehicles and military satellites are thrown into the mix for good measure

Political Perspective: Transitioning towards Charismatic Leadership?

The Party Congress work report ended with the announcement of three new slogans: “Serving the People is Serving the Heaven” (이민위천), “Single-minded Unity” (일심단결), and “Self-reliance” (자력갱생). Of the three, “Serving the People is like Serving the Heaven” in particular harkens back to Kim Il Sung, the founder of North Korea and whose look and mannerisms Kim Jong Un is known to emulate1112. A similar concept was promulgated by Kim Jong Un in the early years of his leadership as “People First-ism”13, thereby linking his governing philosophy with those of his father and grandfather.

The new five-year plan as described in the work report represents a return from trade liberalization and management autonomy to the socialist economic principles of hierarchical subordination of enterprises and production units to the state and party. As such, it represents a significant regression from the market friendly approach of the former Premier Pak Pong-ju, who coincidentally announced his retirement from public office in the 8th Party Congress. Although the fate of jangmadang has not been determined under the new five-year plan, economic and manufacturing self-reliance will severely disrupt private markets if implemented, as most of the goods traded in jangmadang in North Korea are imported from China.

The emphasis on “People First-ism” and its re-expression as Kim Il-Sung era’s slogan of “Serving the People like Serving the Heaven” should be understood as a political response to the decline in the North Korean economy caused by sanctions and COVID-19 quarantine measures. Kim Jong Un’s accession to power was followed by a rapidly expanding trade with China, which resulted in jangmadang flourishing in the country. The expansion in trade was reflected in the increase of domestic consumption, as the composition of trade with China changed from being mostly intermediate inputs for the industry to consumer goods. Undoubtedly, Kim could claim credit for the consumption growth as indicated by increase in imports and overall economic stability of the past decade. The annual surveys of North Korean refugees in South Korea conducted by the Institute for Peace and Unification Studies (IPUS) at Seoul National University show that North Korean public’s support for Kim Jong Un has steadily increased since 2012 when he assumed power. Kim’s apparent “popularity” could be due to a number of was based on his ability to deliver economic outcomes for the people.

But with the trade restrictions in place the level of consumption, and therefore the people’s standards of living, is falling precipitously. Kim will no longer be able to claim credit for the economic success of his country, which was an important achievement along with North Korea’s nuclear development. In this sense, one could consider “People first-ism” is simply a substitute for economic development.

The unveiling of a new portrait of Kim Jong Un dressed as a military general reminiscent of his grandfather, the launch of intense propaganda campaign, and the emergence of personality cult around Kim, all demonstrate that “Serving the People is like Serving the Heaven” is not to be taken literally, but interpreted as a rhetorical device for Kim to cloak the failure of his economic policy with the political aura of his predecessors.

The propaganda campaign that has accelerated greatly in 202014 is meant not only to elevate Kim to the same rank as his father and grandfather, but imbue Kim Jong Un with the same level of charisma that his grandfather in particular had enjoyed with the North Korean people. Of course, Kim Jong Un is not Kim Il-Sung. Charismatic leadership cannot simply be acquired by fiat. The political dilemma that lies ahead for Kim is how to enforce followership without the economic rewards that have kept the elites and public in line during the past decade.

Conclusion:

A typical North Korean statement mixes truths with bluffs, even outright falsehoods. For a normal country such a behavior would be detrimental to its national credibility. But in the case of North Korea, which thrives on the outsiders’ perception of it as enigmatic and unpredictable, obvious falsehoods sometimes amplify the impact of its bluffing. The work report of the 8th Party Congress is both an internal and external propaganda piece, with hints of important policy moves mixed in.

The 8th Party Congress work report depicts a picture of a regime without a viable exit strategy from the present conundrum. While to outside observers the regime’s prospect seems bleak, it is only because of the assumption that the North Korean regime aspires to economic growth just like other political entities. In fact, the regime prioritizes political stability over economic growth. The future direction of the economy as outlined in the new five-year economic plan doesn’t offer radical solutions, but instead it points towards economic retrenchment that would shrink the economy while making it more robust. The regime aims to fill the void left by the evaporation of economic gains with Kim’s own personal appeal in the form of “People First-ism” and “Serving the People is like Serving the Heaven”. Whether the regime can impose followership on the public with artificially constructed charisma is unclear.

The only certainty for the regime and the international community is North Korea’s growing nuclear capability. The overall message of the work report is straightforward: North Korea will relentlessly work on building nuclear weapons as before15 by pursuing their miniaturization and diversification. Mass nuclear production is not simply a plan, but the main pillar of North Korea’s nuclear and diplomatic strategy. By amassing more powerful and longer-range nuclear weapons, the North will gain stronger diplomatic leverages and have more options to pursue its strategic objectives. In the end, North Korea’s intention is to convince the United States to abandon its futile objective of pressuring the North to completely denuclearize.

The combination of economic retrenchment and growing nuclear capability raises the prospect of a more intransigent North Korea when it comes to denuclearization. Economic retrenchment should not be interpreted as an indicator of regime’s desperation, but as an active response by the regime to stabilize the economy. Economic measures are meant to reassure the public that is suffering from economic hardship, but the regime will intensify internal control through propaganda and cult of personality at the same time.

A retrenched economy also implies less dependence on foreign trade, which in turn diminishes the impact of sanctions. Kim Jong Un will dig heels in and demand the United States to negotiate over North Korea’s nuclear state status rather than denuclearization. Kim does not seem to be keen on embarking on nuclear adventurism as witnessed in the 2016-17 period, at least for now. But with the predictable failure of the new five plan looming over the horizon, Kim will soon resort to the only credible leverage that his regime still possesses. The advances that North Korea has achieved on nuclear and missile fronts means that this time the North will not relent until the United States is ready to accept it as a de facto nuclear state.

Appendix: Comparison of Five-Year Plans of the 7th and 8th Party Congresses in Other Economic Sectors

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 1. The Guardian. 6 January 2021. North Korea: Kim Jong-un says economic plan a near-total failure at rare political meeting

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jan/06/north-korea-congress-kim-jong-un-economic-plan-failure-mistake-biden - 2. 충북청년신문. 2021년 1월 9일 [전문] 북 노동신문, 제8차 당대회 김정은 국무위원장 사업총화에 대한 보고①.http://www.ynanum-press.kr/news/view.php?idx=212582

- 3. The annual joint military exercise has been downgraded greatly in both scope and scale. Source: Yonhap News. 8 March 2021. S. Korea calls on N.K. to take ‘wise, flexible’ approach toward military exercise with U.S. https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20210308005500325

- 4. For instance, according to Prof. Kim Byung-yeon of Seoul National University, the new five-year plan sets the cement production goal at 8 million tons per year by the end of the five-year period. This figure actually represents more of a recovery than net growth since it is believed North Korea was producing 7 million tons of cement in 2016, which decreased significantly because of the sanctions. Source: 중앙일보. 2021년 2월 3일. 당 대회가 누설한 북한경제의 비밀 https://news.joins.com/article/23984720

- 5. Vinylon, a polyester substitute, is a synthetic fiber that is produced from polyvinyl alcohol, which in turn is made from coal and limestone

- 6. Steel requires coking coal besides iron ore for its production

- 7. Bank of Korea. (2019). Gross Domestic Product Estimates for North Korea in 2015. Bank of Korea.https://www.bok.or.kr/eng/bbs/E0000634/view.do?nttId=10059560&menuNo=400069

- 8. 연합뉴스. 2020년 11월 27일. 북한 ‘광물생산지’ 검덕지구 수해 대대적 복구…2천여가구 건설https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20201127015700504

- 9. RFA 자유아시아방송. 2018년 10월 10일. 북, 원산관광지 개발 위해 건설자재 대량 수입 —https://www.rfa.org/korean/weekly_program/bd81d55cc740-c5b4b514b85c/nkdirection-10102018132727.html

- 10. South Korean government’s concern is palpably reflected on the following statement of the Ministry of Unification spokesperson, Lee Jong-joo :”As the combined exercises are being carried out in a flexible and scaled-back manner in both the size and type of drills, we will strive to support efforts for peace on the Korean Peninsula. We call on North Korea to show a wise and flexible approach corresponding to our efforts to establish stable and lasting peace on the Korean Peninsula,” source: https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20210308005500325

- 11. The Guardian. 27 August 2014. Like grandfather, like grandson: North Korea’s doppelganger leadershttps://www.theguardian.com/world/gallery/2014/aug/27/north-korea-leaders-kim-jong-un-pictures

- 12. 한겨레. 2021년 1월 18일. [유레카] 이민위천, 남북동포에게 밥이 하늘이다http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/opinion/column/979233.html

- 13. 연합뉴스. 2013년 2월 18일. 北, 올해 신조어로 ‘인민대중제일주의’ 부각https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20130218061300014

- 14. NK News. 30 December 2020. Timeline: How North Korean propaganda hyped Kim Jong Un in 2020https://www.nknews.org/pro/timeline-how-north-korean-propaganda-hyped-kim-jong-un-in-2020/

- 15. NBC News. “North Korea launched no missiles in 2018 – But that isn’t necessarily due to Trump,” 27 December 2018 https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/north-korea-launched-no-missiles-2018-isn-t-necessarily-due-n949971

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter