Introduction

In 2014, LGBT rights made headlines in South Korea.1 It became the center of public attention when Seoul Mayor Park Won-soon revealed in an interview with the San Francisco Examiner that he “personally agree[d] with the rights of homosexuals,” and hoped that “Korea will be the first” Asian country to legalize same-sex marriage.2 His credentials as a human rights lawyer added fuel to the fire. Following the interview, conservative groups accused him of supporting homosexuality and opposed the adoption of the Seoul City Charter of Human Rights, which was one of his election pledges during the 2014 local elections. In the face of tremendous opposition, Mayor Park reneged on his commitment and the human rights charter was eventually declared null and void.

Mayor Park’s initial effort to bring the LGBT issue to the fore of South Korean political and social discussion was the first of its kind by a prominent politician. In the past, LGBT was a topic generally shunned by politicians and the public alike. A number of LGBT individuals have been somewhat active in the entertainment industry. But the broader issue has never been regarded as a serious political or social issue.

This issue brief examines South Korea’s attitude toward LGBT using the Asan Institute’s public opinion surveys. Based on survey results, it explores whether the LGBT issue has the potential to become an important political and social topic in the near future. As South Korea moves toward consolidating its democratic and liberal values, increasing attention has been paid to the rights of the individual. LGBT rights, however, have yet to be recognized or addressed. Survey results show that South Koreans continue to be disinterested in LGBT, which has allowed political elites to abstain from engaging the issue.

Institutionalizing LGBT Rights

As South Korea’s democracy continues to evolve, its human rights awareness has undergone changes. Various efforts have been made to abide by the international human rights standards, which have resulted in slow but steady changes to the country’s domestic laws. The court ruling in 2006 to allow a transgender to legally change his/her gender and the abolishment of the patriarchal family registration system in 2008 are two such examples.

However, its attitude toward LGBT has been rather ambivalent. On one hand, it has supported international institutions and norms that protect the rights of LGBT. For example, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has urged all nations to abide by the international human rights standards to protect LGBT from torture, discrimination, and violence. It is a reminder that nations have the obligation to protect all people, irrespective of sex, sexual orientation, or gender identity. South Korea joined this effort on September 26, 2014, when it supported a landmark UN resolution aimed at combatting violence and discrimination against LGBT.

On the other hand, LGBT issues have been a major ‘deal breaker’ in South Korea’s legislative politics. For instance, an anti-discrimination bill aimed at reinforcing the country’s commitment to basic human rights was proposed in 2007. The bill was met with fierce opposition from conservative groups because it initially specified sexual minorities as one of its principal beneficiaries. The bill was proposed again in 2010 and 2013. But it was ultimately repealed on April 24, 2013 without a chance for a vote in the National Assembly.

On October 10, 2014, a human rights education bill aimed at educating government employees on human rights issues was motioned by congressperson Yoo Seung-Min. This particular bill was significant because it was the result of a rare bipartisan effort. It was co-sponsored by Lee In-je (Chairman of the Supreme Council of the Saenuri Party), Joo Ho Young, (Chairperson of the Policy Committee of the Saenuri Party) and Park Jie-won (senior member of the New Politics Alliance for Democracy).3 Despite the bipartisan push, the bill was met with strong opposition from a number of Christian and conservative groups who argued that the bill promoted homosexuality.4 The bill was repealed on November 6, 2014.

The debacle over Mayor Park Won-soon’s initiative to adopt the Seoul City Charter of Human Rights was one of the first instances in which the LGBT issue received national attention. In June-July 2014, the Seoul Metropolitan Government organized a Citizens’ Committee composed of 150 civilian representatives and 30 experts to review the charter.5 Through six meetings, the committee unanimously passed 45 of the 50 charter clauses. Among the remaining five, the clause prohibiting discrimination based on one’s sexual orientation and sexual identity became the center of national attention. This clause became controversial when Mayor Park’s aforementioned interview with the San Francisco Examiner was picked up by the Korean media. Protestants and other conservative groups criticized the charter for promoting homosexuality and staged a mass protest in City Hall.

Faced with heavy opposition, the Seoul Metropolitan Government announced that the remaining clauses of the charter had to pass unanimously. When the votes were tallied, 60 voted ‘yes’ and 17 voted ‘no.’ The Seoul Metropolitan Government then overruled the Citizens’ Committee and announced that the charter had failed. The situation was exacerbated when Mayor Park revealed in a meeting with a group of Protestant Church leaders on December 1 that he does not support homosexuality. Subsequently, LGBT advocacy groups staged a mass protest in City Hall. When the Seoul Metropolitan Government cancelled all events planned for the World Human Rights Day on December 10, the Citizens’ Committee independently announced the adoption of the human rights charter. Mayor Park apologized, stating that “it [the charter] is not worth pursuing if it causes social division.” Shortly thereafter, the Seoul Metropolitan Government officially announced that the Seoul City Charter of Human Rights was repealed.

This incident showed the potential for LGBT to become an important political agenda in South Korea. At the same time, it showed just how sensitive the LGBT issue is for any politician to tackle.

South Korean Public Opinion on LGBT Issues

Attitude Toward Homosexuality and Same-Sex Marriages

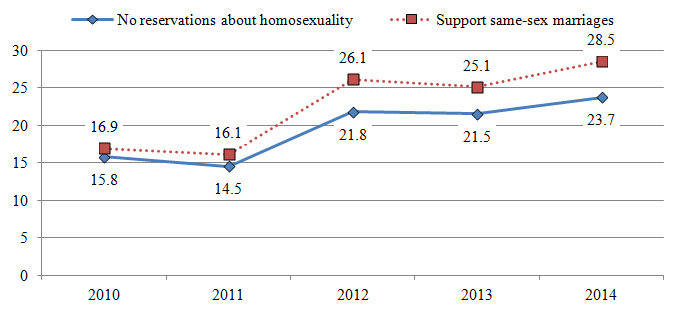

Given the growing recognition of LGBT in South Korea, it is important to gauge how South Koreans understand and interpret these issues. According to the Asan Institute for Policy Studies’ Annual Surveys conducted from 2010 to 2014, South Koreans have become more tolerant of homosexuality and supportive of same-sex marriages.6 As shown in Figure 1, the number of respondents who showed no reservations about homosexuality increased from 15.8% in 2010 to 23.7% in 2014. Concurrently, those who supported the legalization of same-sex marriages rose from 16.9% in 2010 to 28.5% in 2014.

Figure 1. Changing Attitude toward Homosexuality and Same-Sex Marriages (%)

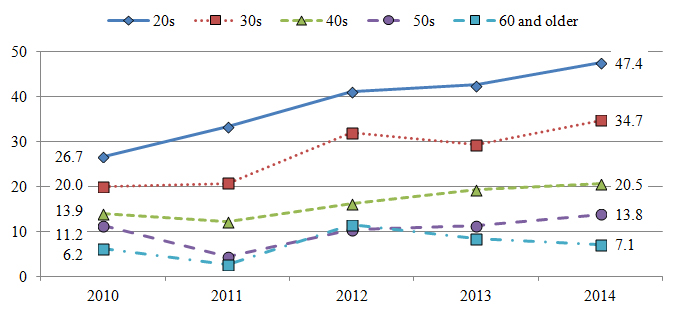

An Asan Poll conducted in December 2014 demonstrated similar results.7 32.8% of respondents showed open-mindedness about LGBT. The changing attitude toward LGBT was especially noticeable among younger respondents. As Figure 2 exhibits, 26.7% of respondents in their 20s were open-minded about homosexuality in 2010. This figure almost doubled in four years, reaching 47.4% in 2014. In contrast, respondents who were 50 and older did not change their views substantially over the past few years.

Figure 2. Tolerance of Homosexuality by Age (%)

Younger South Koreans appeared to be more supportive of same-sex marriages as well.8 In 2010, 30.5% and 20.7% of respondents in their 20s and 30s, respectively, supported the legalization of same-sex marriages. In 2014, these numbers almost doubled to 60.2% and 40.4%. In contrast, 14.4% of respondents in their 50s and 6.5% of those who were 60 and older supported same-sex marriages in 2010. The numbers remained relatively unchanged in 2014 (50s: 14.5%, 60 and older: 8.3%).

Religion appeared to play an important role in determining respondents’ attitude toward LGBT issues.9 70.6% of Protestants had reservations about LGBT (23.6% answered that they did not). On the other hand, those who did not associate themselves with any religion were more accepting of LGBT (39.6% responded that they had no reservations while 48.9% said they did). Interestingly, we observed a significant disparity between Catholics and Protestants. 41.9% of Catholics expressed reservations about LGBT (49.4% indicated the opposite). Pope Francis’ embrace of the LGBT community may have contributed to the Catholics’ relatively open attitude.10

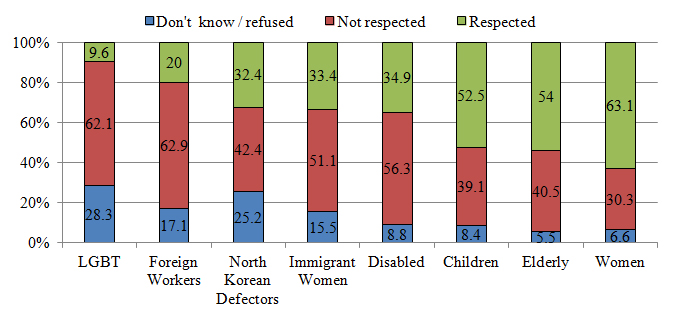

While the Korean society in general is yet to be more understanding of LGBT, a considerable portion of South Koreans agreed that the human rights of LGBTs were not being respected (See Figure 3). According to the Asan Institute’s August 2014 public opinion survey, only 9.6% of respondents answered that LGBT rights were being respected.11 This drew stark contrast to the numbers for women (63.1%), elderly (54%), and children (52.5%).

At the same time, survey results showed that many South Koreans did not have a clear awareness of LGBT as a human rights issue, as 28.3% of respondents said that they did not know or refused to answer. This was 4-5 times the numbers for women (6.6%) and elderly (5.5%). This shows that while the South Korean public is sympathetic of the LGBT community, it is yet to have a firm stance and does not consider LGBT rights as a particularly urgent issue at this point in time.

Figure 3. Awareness of Human Rights Issues (%)

Public Opinion on the Anti-Discrimination Law

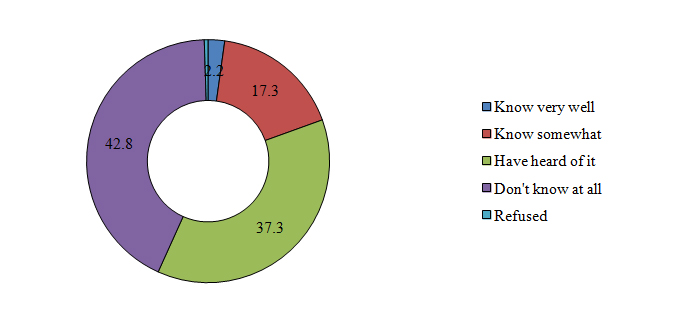

With LGBT issues becoming more socially visible, an increasing number of advocacy groups have urged the introduction of laws that protect the rights of LGBT. The right not be discriminated against based on one’s sexual orientation and sexual identity, the right to start a family, and the right to legally change one’s gender have been at the core of the movement so far. Despite efforts by these advocacy groups to pass important legislations, many South Koreans appear uninterested. For instance, when the 2014 Asan Poll asked South Koreans whether they were aware of the Anti-Discrimination Law, 42.8% of respondents indicated that they ‘don’t know the law at all,’ 37.3% responded that they were ‘aware of it,’ 17.3% said they ‘know somewhat,’ and only 2.2% knew it ‘very well.’ (See Figure 4)

Figure 4. Awareness of the Anti-Discrimination Law (%) 12

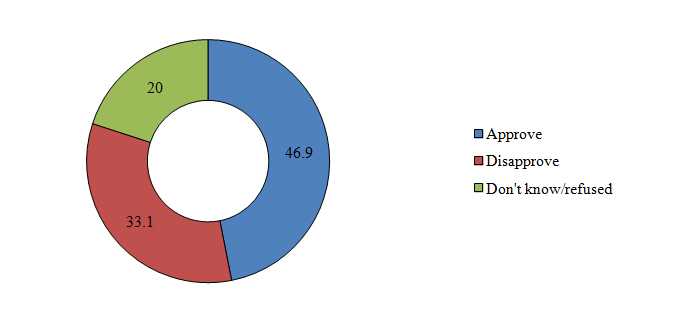

As a follow up to the above question, we asked respondents (who indicated that they knew the law) what they thought about the law (See Figure 5).13 46.9% of respondents approved while 33.1% disapproved the law. 20% indicated that they did not know or refused to answer. In short, the majority of those who were aware of the Anti-Discrimination Law approved the adoption of the law. But, in total, only 9.1% of South Koreans were ‘somewhat’ or ‘very’ knowledgeable of the law and approved its enactment.

Figure 5. Opinion on the Anti-Discrimination Law (%) 14

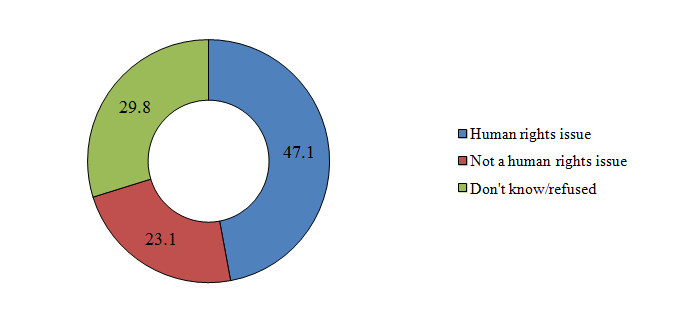

As Figure 6 shows, when we asked about LGBT rights, 47.1% agreed that they were fundamentally a human rights issue. 23.1% disagreed while 29.8% of respondents answered that they did not know or refused to answer, showing a lack of interest in the issue.

Figure 6. Are Issues Related to Sexual Minorities Fundamentally a Human Rights Issue?15

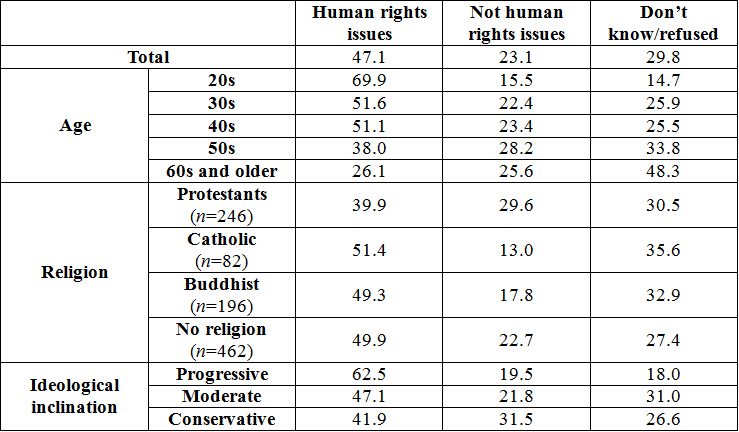

Answers to the above question diverged along age, religion, and ideological inclination (See Table 1). Younger South Koreans appeared to have a better understanding of LGBT. Almost half of those aged 40 or younger (20s: 69.9%, 30s: 51.6%, 40s: 51.1%) considered LGBT issues as human rights issues. Among them, almost 70% were in their 20s. Such findings are in line with our previous statement that the younger generation is more tolerant about homosexuality, same-sex marriages, and sexual minorities in general. But Koreans who were 50 and older had a generally different view. Only 38.0% of respondents in their 50s considered LGBT as a human rights issue. Respondents older than 60 expressed even stronger reservations (only 26.1% answered that LGBT issues were human rights issues). In addition, 33.8% and 48.3% of those in their 50s, and those who were 60 and older, respectively, answered that they did not know or refused to answer.

The responses diverged by religion as well. 51.4% of Catholics, 49.3% of Buddhists, and 49.9% of those with no religion viewed LGBT within the framework of human rights. However, only 39.9% of Protestants agreed with them. The number of Protestants that did not consider LGBT issues as human rights issues (29.6%) was highest among all religious groups.16

A respondent’s ideological inclination also appeared to play an important role. 62.5% of progressives agreed that LGBT was a human rights issue, while 41.9% of conservatives and 47.1% of moderates answered the same. It was notable that a substantial number of moderates (31.0%) and conservatives (26.6%) did not know or refused to answer. This implies that progressives have a firmer stance on the issue of LGBT discrimination than other ideological groups.

Table 1. Are Issues Related to Sexual Minorities Fundamentally Human Rights Issues? (%) 17

Public Opinion on Repealing the Human Rights Charter

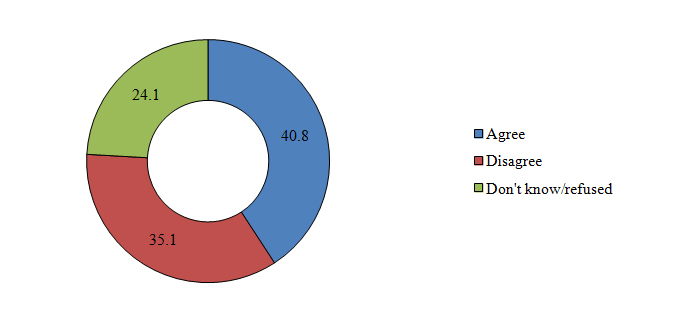

We asked South Koreans how they felt about the Seoul Metropolitan Government’s decision last year to repeal the Human Rights Charter.18 40.8% of respondents answered that repealing the charter was the right thing to do, considering the social division it would have caused. On the other hand, 35.1% stated that human rights issues were non-negotiable and, therefore, the charter had to be adopted. One out of every four respondents (24.1%) answered that they did not know or refused to answer.

Figure 7. Do You Agree or Disagree with the Repeal of the Human Rights Charter? 19

Politicizing LGBT Issues

Asan’s December Poll revealed a noticeable disparity between progressives and conservatives. 50.8% of progressives showed open-mindedness about homosexuality while a significantly smaller 21.8% of conservatives answered the same (44.2% and 72.5% of progressives and conservatives, respectively, indicated the opposite). When asked how they would respond if they found out that their family members were LGBT, 83.6% of progressives answered that they would accept or at least make an effort to accept the LGBT family members (14.1% said they would distance themselves). On the other hand, 60.9% of conservatives said that they would accept the LGBT family members (34.7% said they would distance themselves).

Given the apparent disparity between progressives and conservatives, one may argue that LGBT rights can become a major issue that divides South Koreans along the ideological spectrum, much like the way economic democratization, unification, and national security have in the past. A number of examples in this issue brief suggest that this may be the case. Almost half of South Koreans today think that discrimination against sexual minorities is fundamentally a human rights violation. Furthermore, the younger generation has shown greater sympathy toward LGBT. As globalization and the Internet expand our access to information on the LGBT movement taking place around the world, we could see a favorable political climate developing for the LGBT movement.

However, it is worth noting that public opinions do not always determine government policies. Studies suggest that two factors are influential in the way public opinions influence legislative politics: salience and preference.20 Namely, a politician actively promotes a certain issue when the issue is deemed important and constituency preference is easily identified. On the other hand, if the issue is considered less important and constituency preference is unclear, politicians act in two different ways. First, they can promote the issue based on their personal convictions. This makes sense given their constituents’ lack of interest. Second, they can choose to ignore the issue. Why invest time and effort when their constituents are not interested?

This leads us to project that LGBT is unlikely to become a salient political topic in South Korea for the foreseeable future. As seen in Asan’s public opinion polls, many South Koreans are simply not interested in LGBT issues at this point in time. Economy and national security issues with North Korea will always outrank LGBT rights, which lack the appeal that politicians from either end of the ideological spectrum seek.

There is no denying that public attitude toward LGBT is improving, especially among younger South Koreans. However, public preference on the issue remains unclear, as evidenced by the large number of South Koreans who responded that they ‘don’t know.’ As long as the political costs and benefits of politicizing the issue remain unknown, it will be difficult for any politician to take an active stance.

There are also institutional hindrances that prevent LGBT issues from being politicized. For example, 75% of South Korean congressmen are elected from their local districts. LGBT people in South Korea do not live in clusters and typically hide their identities, making it difficult to create a voting bloc that can pressure political leaders to act. Political leaders, therefore, do not have the incentive to bring LGBT issues to the political discussion. In this regard, foreign workers in South Korea who usually live in a cluster are better positioned than LGBT people to advance their agenda.

These are some of the reasons why Mayor Park’s initiative to adopt the Seoul City Charter of Human Rights carried major significance. His experience as a human rights activist and political standing as one of the frontrunners for the next presidential election provided the push that the LGBT movement lacked in the past. But his decision to reverse position and let the charter fail sent a powerful message to both the political elites and the public. For political elites, it confirmed LGBT as an issue with enormous political costs and little or no benefit. To the public, it reinforced the negative stigma that even the most progressive politician opposes homosexuality.

Quo Vadis?

LGBT issues are subjected to ‘moral politics,’ which often impedes rational negotiations and invites clashes of dogmatic positions. In moral politics, how one ‘frames’ the issue is crucial to winning the battle. As such, LGBT advocates in South Korea face an uphill battle. For example, when the Seoul City Charter of Human Rights, the Anti-Discrimination Law, and the Human Rights Education Bill were first introduced, conservatives framed these issues so that advocates were seen as promoting homosexuality. However, the Human Rights Charter and the Anti-Discrimination Law intended to prohibit discrimination, not promote homosexuality. In fact, the Human Rights Education Bill did not even contain any reference to sexual minorities. Nonetheless, the conservatives were able to frame the issue to their advantage, forcing a prominent political elite such as Mayor Park Won-soon to renege on his commitment.

Given the political climate in South Korea, how can LGBT become politically relevant? The first step is to gain public empathy. But obtaining public empathy is impossible without raising public awareness. As Asan’s survey results show, many South Koreans fail to grasp the importance of LGBT rights and are unaware of the violations taking place within the community. When more South Koreans recognize that LGBT people are being disrespected and discriminated against, they can help transform the issue into a critical social and political topic that merits urgency and attention. LGBT activists can achieve this if they frame the issue within the universal context of anti-discrimination and human dignity, rather than seek privileges for the LGBT people. Only then will they have a fighting chance, if any.

2010

Sample size: 2,000 respondents over the age of 19

Margin of error: +2.2% at the 95% confidence level

Survey method: Mixed-Mode Survey employing RDD for mobile phones and online survey

Period: August 16 – September 17, 2010

Organization: Media Research

2011

Sample size: 2,000 respondents over the age of 19

Margin of error: +2.2% at the 95% confidence level

Survey method: Mixed-Mode Survey employing RDD for mobile and landline telephones

Period: August 26 – October 4, 2011

Organization: EmBrain

2012

Sample size: 1,500 respondents over the age of 19

Margin of error: +2.5% at the 95% confidence level

Survey method: RDD for mobile and landline telephones and online survey

Period: September 24 – November 1, 2014

Organization: Media Research

2013

Sample size: 1,500 respondents over the age of 19

Margin of error: +2.5% at the 95% confidence level

Survey method: RDD for mobile and landline telephones and online survey

Period: September 4 – September 27, 2013

Organization: Media Research

2014

Sample size: 1,500 respondents over the age of 19

Margin of error: +2.5% at the 95% confidence level

Survey method: RDD for mobile and landline telephones and online survey

Period: September 1 – September 17, 2014

Organization: Media Research

Asan Daily Poll

Sample size: 1,000 respondents over the age of 19

Margin of error: +3.1% at the 95% confidence level

Survey method: RDD for mobile and landline telephones

Period: See report for specific dates of surveys cited

Organization: Research & Research

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 1LGBT is an acronym for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender.

- 2Joel P. Engardio, “Seoul Mayor Park Won-soon wants same-sex marriage in Korea as first in Asia,” The San Francisco Examiner, 12 October 2014, http://www.sfexaminer.com/sanfrancisco/seoul-mayor-park-won-soon-wants-same-sex-marriage-in-korea-as-first-in-asia/Content?oid=2908905.

- 3The Saenuri Party is the ruling party.

- 4On the contrary, the education bill does not contain information about allowing or supporting homosexuality. The goal of this bill was to follow the examples of other democratic countries that mandate such education to government employees.

- 5Civilian representatives were picked randomly through a draw regardless of age, gender, and residence.

- 6Asan Annual Surveys (2010-2014). Two questions were asked to measure the level of reservations that South Koreans have about homosexuality and the support for same-sex marriages. First, we asked respondents, “How do you feel about homosexuality?” They were given four choices: 1) No reservations at all; 2) No reservations in general; 3) Have some reservations; and 4) Have great reservations. Second, we asked respondents, “What do you think about the legalization of same-sex marriages?” They were given four choices: 1) Very much agree; 2) Somewhat agree; 3) Somewhat disagree; and 4) Very much disagree.

- 7Asan Poll (December 6-9, 2014). We asked respondents, “How do you feel about lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender?” They were given four choices: 1) No reservations at all; 2) No reservations in general; 3) Have some reservations; and 4) Have great reservations.

- 8A graphical analysis of the results on same-sex marriages is not included in this issue brief.

- 9Oppositions to the Anti-Discrimination Law come from Protestant groups centered around the church. These groups include the National Assembly Missionary Alliance, the National Assembly Morning Prayer Group, the World Holy City Movement, and the Christian Public Policy Consultation Association. In August 2013, the National Assembly Morning Prayer Group organized a special task force committee to prevent the introduction of the Anti-Discrimination Law. Leading the National Assembly Morning Prayer Group at the time was Mr. Hwang Woo-yeo, the current minister of education and deputy prime minister for social affairs.

- 10“Gay Rights Groups Hail New Catholic Tone,” The New York Times, 10 October 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2014/10/10/world/europe/ap-eu-rel-vatican-family.html.

- 11Asan Daily Poll (August 29-31, 2014). We asked respondents, “Do you think the human rights of the following groups are being respected?” They were given four choices: 1) Very much respected; 2) Somewhat respected; 3) Not respected very much; and 4) Not respected at all. Groups included LGBT, foreign workers, North Korean defectors, immigrant women, the disabled, children, elderly, and women.

- 12Asan Poll (December 6-9, 2014). We asked respondents, “Have you heard of the law that prohibits discrimination based on one’s sexual orientation?” They were given four choices: 1) Know very well; 2) Know somewhat well; 3) Have heard of it; and 4) Don’t know at all.

- 13We asked respondents, “What do you think about the anti-discrimination law?” They were given four choices: 1) Very much approve; 2) Approve somewhat; 3) Disapprove somewhat; and 4) Very much disapprove.

- 14Asan Poll (December 6-9, 2014).

- 15Asan Poll (December 6-9, 2014).

- 16We measured the ideological inclination of the respondents by asking them the following question, “From 0 to 10 (0 being most progressive and 10 being most conservative), how would you rank your ideological inclination?” This question was asked pertaining to political, economic, and social issues. Therefore, we acknowledge that there is an inherent danger in using this result to examine the LGBT issue.

- 17Asan Poll (December 6-9, 2014).

- 18We asked respondents the following question, “Mayor Park Won-soon’s initiative to adopt a human rights charter was repealed recently. Which of the following statements do you most agree with?” They were given two choices: 1) Agree with the repeal because of the social division it would cause; and 2) Disagree with the repeal because human rights are non-negotiable.

- 19Asan Poll (December 6-9, 2014).

- 20Jeffrey R. Lax and Justin H. Phillips, 2009, “Gay rights in the States: Public Opinion and Policy Responsiveness,” American Political Science Review, 103(3):367-386.;

Donald P. Haider-Markel and Kenneth J. Meier, 1996, “The Politics of Gay and Lesbian Rights: Expanding the Scope of the Conflict,” The Journal of Politics, 58(2): 332-349.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter