Jeremy Ghez,1

Academic Director, Center for Geopolitics, HEC Paris

Chong Woo Kim,

Research Fellow, The Asan Institute for Policy Studies

The analysis presented in this paper reflects the views of seminar participants only.

There has been hardly any research done on what sort of reactions we would get from the business community in the aftermath of a North Korean collapse. What little efforts we have seen came from South Korean government agencies and not the real business community. At the same time however, this same business community often proves to be a stakeholder—albeit an unwilling one—in international crises and in reconstruction efforts across the globe. Understanding its reactions—and overreactions—and its analyses could help policymakers anticipate the effects of deep and abrupt political change.

Today, speculation about the reasons for Kim Jong-un’s disappearance should remind policymakers and regional stakeholders of how significant the issue is. In practice, it is very difficult to discuss this matter with business leaders. It is with this observation in mind that one of us (J.G.) designed a simulation scenario for the HEC Paris-Leadership Certificate for a very broad audience—ranging from individuals who just finished business school to MBA and EMBA participants.

This simulation exercise involving students has enabled us to get a glimpse into how the business leaders would think through the situation and react in the real world if a similar scenario were to happen. We have drawn the following conclusions from this simulation:

√ Public-private partnerships can be a meaningful tool for crisis management and in rebuilding efforts. The business community in Asia has vested interests in the stability and the prosperity of the region that can overlap with neighboring governments.

√ While North Korea does not hold the only key to solving the Asian paradox—that is, the growing security challenges this region currently faces despite ever-closer economic interdependence—, greater stability and openness in the country could help regional stakeholders overcome it. It is important that the long-term dividends of greater stability be made clear in official strategies, as these may not be so clear in the minds of business decision-makers who may overlook long-term opportunities in the region.

This paper looks to present the scenario that was given to participants and the way they reacted to this fictional crisis. The simulation exercise has raised some issues that need to be discussed and further integrated into contingency plans—so the paper concludes with a discussion of policy implications that this simulation has led us to consider.

The Scenario: From the Death of Kim Jong-un to a New Emerging Economy

The scenario, divided up in four different days, describes the aftermath of the fall of the current North Korean regime. Throughout the scenario, the Koreas remain two separate countries. The issue of reunification only arises at the end of the scenario.

On day 1, North Korean supreme leader Kim Jong-un is assassinated in undisclosed circumstances. While Choe Ryong Hae announces the death of the “Dear Leader” and thus positions himself as the natural successor, there quickly appears to be an unmanaged power vacuum in Pyongyang. Participants are told that a North Korean expert based in China suggested that with no sustainable plan to maintain power, all candidates for the North Korean leadership preferred to flee rather than to deal with an extremely shaky situation. There seems to be no real obvious solution to this situation, adds a source close to the Elysée Palace in Paris, who expects significant tensions between different factions within the North Korean military or the former establishment, between China and the United States on the question of securing the country’s nuclear material and between Beijing and its neighbors, in particular if the former has no convincing long-term plan to offer to the latter.

Day 2 is set six months later. It recaps the series of events that took place since the assassination of Kim Jung-un and describes the challenges that the country, the region, and the international community still face in North Korea. Participants learn that Ban Ki-moon resigned as UN Secretary-General to become the first UN Special Representative and Head of the UN Interim Administration Mission in North Korea (UNMINK). While he recognizes that reconstruction efforts would need to be phenomenal, Ban Ki-moon repeatedly indicates that with the support of the international community and the private sector, North Korea had the potential to become a dynamic economy. In his “roadmap for North Korea,” Ban puts forward his goals: stabilize the country and contain the risk of internal strife, modernize the North Korean infrastructure, guarantee the population’s welfare and find a solution to all ownership-related disputes and finally find a “durable solution for North Korea’s integration in the broader Asian continent.” He calls upon the rest of the international community, including private sector actors, to participate in the reconstruction effort so as to guarantee the long term stability of the region. Participants are told that when interviewed by NHK World, one South Korean expert expressed his surprise that no one, including in his own country, was talking about reunification.

An abrupt amelioration occurs in day 3, which takes place two years after the fall of the North Korean regime. News headlines about North Korea reflect the enthusiasm around the rise of the country as a new emerging economy and as a huge potential market for consumer goods. But because of those ravages of dictatorship, not everyone shared the prevailing optimism about North Korea, which remains on life support and still at risk of implosion. In addition, North Korea is on the verge of becoming an additional theatre of the Western-Russian rivalry and of Western-Chinese tensions. On the ground, the economic matchup opposed Western and regional infrastructure and energy companies. China is omnipresent, mainly because Beijing fears losing the upper hand in the region. Those fears, however, were somewhat surprising to most: Chinese companies, in the end, had the upper hand in most of the sectors relevant to North Korea’s reconstruction.

On the final day, which takes place five years after the fall of the regime, the country is “modernizing and on its way to normality,” in the words of Ban Ki-Moon, who announced the forthcoming elections in North Korea. Several businesses entered the country and were doing business almost normally. Other companies found it hard to navigate in a landscape with so significant structural vulnerabilities. Others, still, found it hard to tailor their products, no matter how successful these were in the past, to local realities. For instance, a famous and popular American smartphone and computer manufacturer’s attempt to sell a cheap version of one of its products is a total failure: distrustful consumers believe the tool was designed to monitor their every move and to replicate what the former regime was trying to achieve while others claimed that unless a Western company could offer as reliable products as it did to the rest of the world, it should not bother to come to North Korea. This last argument echoes a broader political debate about the future of North Korea, a country with no real democratic tradition. A nascent, nationalist movement primarily denounced foreign presence in the country and sought “independence from Western occupation.” On the other side of the political spectrum was the Democratic Party of North Korea, seeking reunification with the South and relationships with all of the country’s immediate and more distant neighbors. The relevance and desirability of a free-market economy and the question of the relationship to South Korea are the two crucial topics of this political struggle.

Run to or away from the Region? Reactions from the Private Sector

Participants had a week to deal with each of the four days of the scenario. For each day, teams of four or five participants were expected to provide a detailed set of recommendations to the CEO of a leading fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) company based in Europe, as events unfolded on the ground.

The initial challenge: broadening your intellectual comfort zone

During the early stages of the game, participants were completely out of their comfort zone. The real challenge for many of the teams was to translate the results of their analysis of a fictional scenario into a practical and actionable strategy, to reconcile the short-term risks with the long-term opportunities. It is not surprising to identify two very opposite sets of individuals in these circumstances: those who wish to remain extremely cautious given their discomfort with a theme they have never dealt with and those that feel extremely confident about the likelihood of a specific trajectory in this crisis, the limited amount of information provided by the scenario notwithstanding. Unsurprisingly, perhaps because of the design of the game, this setting often led participants to panic rather than to act on informed analysis.

For instance, the natural—and perhaps legitimate—inclination of these business-oriented profiles is to over-focus on the present and to consider asset protection and shareholder confidence the unique priorities—thereby giving the scenario of durable tensions or full-blown war a high likelihood and overlooking to some extent any medium- or long-term opportunity. When some attempted to go beyond this natural inclination, they were tempted to develop bold strategies based on the company’s track record and positions in Russia and in China—overlooking the particularities of the potential North Korean market. Alternatively, others tried to control geopolitical dynamics by speculating what would happen next, in an effort, perhaps, to set boundaries to a seemingly intractable problem. This included speculation about who would succeed Kim Jong-un when the scenario made it clear that there was a power vacuum in Pyongyang. Participants were quick to acknowledge that no matter how hard they tried, they would have very little control over these dynamics in practice.

While these reactions are not unusual or unexpected, they could, in practice, undermine further the region’s ability to rebound, especially at a moment when the region could benefit most from economic activity or brighter economic prospects.

The ultimate challenge: addressing the ‘so-what?’ question

In the end, participants were expected to provide a roadmap for action—whether it led to stay out or go in. This required them to recognize—as most did—the salient characteristics of the new landscape, beyond the noise, as well as the fact that the situation is by no means a static problem.

While the scenario contained several quirky and anecdotal developments, it was useful—without excessively oversimplifying the issue—to remember three basic realities: 1) a deep political change occurred in North Korea and Ban’s efforts notwithstanding, the country’s stability was rather uncertain; 2) North Korea, as small and as economically irrelevant as it seemed, still represented a major stake for regional and global actors, including China and the United States and 3) as the famous US smartphone and computer manufacturer’s epic failure in day 4 reminds us, there is likely to be no silver bullet for companies who want to approach this new market. Even in this seemingly complex situation, one can identify, beyond the noise, the most significant features driving the landscape.

In addition, the scope of the problem kept on changing. In the beginning, as they were often amused and entertained by the scenario, participants often had one specific trajectory in mind and were vulnerable to quick changes of situations on the ground. Ultimately, they quickly realized that they needed to recognize the changing scope of the problem and to identify the milestones that they would expect before moving forward and the elements that would constitute red lights for further action. In this scenario, while the issue of domestic political stability in North Korea is persistent from day 1 through day 4, the question of North Korea’s relationship to the rest of the world is ever-changing. In the early phases of the game, the risk of a regional war, which would cut off North Korea from the rest of the world further, is predominant in everyone’s mind. By the end, the question shifts from whether war can be avoided to whether North Korea can actually open up to the rest of the world economically and culturally.

Participants sought to identify the appropriate metrics of a promising trajectory—that is, a trajectory that would be a green light for business development. In the short run, most claimed, those metrics concentrated on short-term improvements of the economic well-being of the population and the economy, as well as the degree to which political instability was contained. In the medium run, the metrics concentrated on the successful development of infrastructure and its ability to durably contribute to political stability. In the long run, those metrics focused on the emergence of a consumer good market in North Korea.

The key issues that seemed largely unresolved related to political stability in North Korea—would it be another failed state in one of the most economically dynamic regions of the world—as well as the country’s relationship to the rest of the world—how open would the North Korean economy be ultimately. Many participants wondered how sustainable the rebuilding efforts were given the persisting doubts regarding North Korea’s ultimate degree of openness. In practice, participants were wary of what instability in North Korea could mean for the region and whether it could be the source of tensions between China and the United States. Participants also worried that the country’s inability to open up—both in terms of trade flows and in terms of human connections to the rest of the world—could undermine the benefits of political change even if North Korea became a stable country.

Finally, it is also noteworthy that participants looked at the broader implications of the fall of North Korea. In particular, many groups noted how central the Asian market had become for consumer-good firms. Though they were presented with evidence that the fall of the regime in North Korea could energize the region as a whole, most participants were fearful of the destabilizing effects this would have and pointed to other opportunities around the globe, namely in African and Latin American emerging markets. This hedging approach showed that now, more than ever, globalization is about interconnectedness and that one crisis could have global effects.

Implications for the Private Sector, for South Korea

Participants were not all familiar with Asian security issues—let alone North Korean ones. However, it is worth pointing out that this exercise raises specific questions about the implications of a succession crisis in North Korea and about the contingency plans that the country’s neighbors may need to think about. In particular, we draw two sets of issues: the role that the public-private partnership can play as a crisis management tool in the short run, and how this tool could help South Korea overcome the Asian paradox.

The public-private partnership in Asia: A tool for crisis management?

Leadership is an increasingly popular topic in academia and in business schools in particular. In practice, leadership may come in different forms and may require individuals to master a wide array of skills. These skills relate to managerial and business issues. But they also relate to a more atypical set of issues for business curricula, including societal, historical, and geopolitical questions.

Similarly, Michael Porter’s argument about shared value has experienced growing traction in business schools. Porter’s argument—namely that business expenditures that aim at social improvement may be in a firm’s benefit especially if they contain negative externalities that can increase a firm’s vulnerability or harm its productivity—is also an invitation to business leaders to consider their external environment through a broader lens than before. To this extent, this exercise was not only about North Korea, but also about how a change in Pyongyang would affect—and perhaps energize—the region as whole, and more broadly, about how business executives could and should think about global change more strategically.

This means that business leaders are increasingly trained to think and to make sense of their external environment. As a result, regional authorities can consider them at least as interlocutors and at best as long-term partners in the rebuilding effort. In practice, during a crisis, communication between the public and private sectors can contain the most detrimental fallouts of the crisis. In fact, the ability of the region’s governments to reassure private actors so as to limit the degree to which they will be tempted to flee or to excessively focus on short-term dynamics is likely to have a significant influence on the success of a regional rebound and of the reconstruction efforts in North Korea. It is worth noting the metrics and signposts that the business community is likely to use in this case and that this experiment shed light on are actually straightforward. Regional authorities could use these to better align public and private interests.

Overcoming the Asian Paradox

This simulation may also have implications for the long run, regardless of the type of crisis that could materialize in North Korea.

For obvious reasons, analysts are often tempted to reduce the North Korean question to a security issue. Pyongyang’s erratic behavior, nuclear ambitions, and ability to create uncertainty and chaos regionally fully justify this focus. In addition, younger generations in South Korea seem far more skeptical and far less attached to reunification than their parents were. The result of this state of affairs is that there seems to be nothing to win in North Korea—just risks to contain.

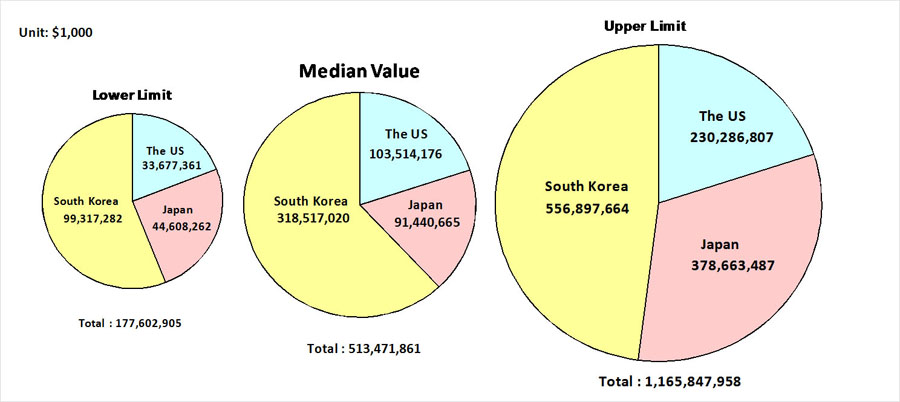

However, greater stability and openness in North Korea could help the region overcome what is known as the Asian Paradox. To put it simply, the Asian Paradox refers to the growing security challenges this region currently faces despite ever-closer economic interdependence. The shape of this region’s future will be determined by the extent to which this paradox has been successfully resolved. No doubt there will be many obstacles to overcome, but resolving North Korea’s nuclear issue is central for peace and regional cooperation. Should the region be prudent enough to take a path towards peace and prosperity, a recent study has estimated that there could be additional economic benefits of half a trillion US dollars from the distance effect in trade between China’s northeast provinces (i.e., Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang) and South Korea, Japan, and the United States combined over the period from 2015 to 2030 as shown in Figure 1. This is only possible under the assumption that North Korea strictly adheres to international standards and that there is an open access to North Korean territories for shorter trade routes directly connecting China and South Korea. This will, in turn, spur economic growth in North Korea. To this effect, South Korean President Park Geun-hye has proposed the “Northeast Asia Peace and Cooperation Initiative” to capitalize on the region’s assets and to meet the region’s security challenges. An alternative path leading to confrontation and conflict will certainly not be a zero-sum game. It will be a loss to every stakeholder.

Figure 1. Cumulative Economic Benefits from the Distance Effect between China’s northeast provinces and South Korea, the US, and Japan from 2015 to 2030.

Source: Korea International Trade Association

This is therefore not only a diplomatic effort. In the past, there has been too much focus on the cost of reunification and too little on the long-term economic returns expected from reunification. This certainly has dampened South Koreans’ enthusiasm for reunification with North Korea. Though how one defines “the cost of reunification” is far from clear, the word “investment” would be a better choice. In February 2014, President Park has chosen the term “daebak” meaning “bonanza” to describe the huge economic benefits reunification with North Korea will bring to the region.

This evolution has helped policymakers give the discussion a more pragmatic tone and to focus the conversation on other issues along with security. For instance, South Korean policymakers could pursue this to the point where clear signals could be sent out to the business community—both domestic and international—about the government’s intention on issues such as land and factory ownership in North Korea if the country were to collapse. It is worth engaging with the business community to shift the terms of the debate and to emphasize that a political change in Pyongyang would have the potential to energize the whole market, and our study on trade has shown in part that it will be a win-win for all actors and all generations in the region, contrary to perceptions.

As this exercise suggests, private sector leaders are certainly not insensitive to this issue, but may likely be fearful in the initial stages if impressive political and geopolitical dynamics dominate the headlines. One of the natural reflexes of business leaders is to hedge by looking for what they see as equivalent opportunities. In particular, instability in North Korea could durably dampen the region’s prospects and lead the private sector to look for other opportunities in Africa and in Latin America. More than ever, globalization has encouraged business leaders to take a holistic look at the world. Persistent instability, even if it is contained, could durably penalize a region in favor of others. This suggests that one of the critical factors for increasing South Korea’s ability to contain the short-term risks and capitalize on the economic gains of a political shift is to involve the private sector, both the domestic and the international ones.

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 1The author would like to thank all the participants of the game for contributing to this analysis through their outstanding remarks and their candid reactions. In particular, he is particular grateful for Serge Camus’s and Vijay Tirumala’s thoughtful comments and help throughout the process.

- 2Michael E. Porter and Mark R. Kramer, “Creating Shared Value,” Harvard Business Review, January/February 2011.

- 3Chong Woo Kim, Open North Korea: Economic Benefits to China from the Distance Effect in Trade, Issue Brief Vol. 10-2014, The Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 4http://www.mofa.go.kr/ENG/North_Asia/res/eng.pdf

- 5This is reprinted from reference number 3.

- 6Bruce W. Bennett , Preparing for the possibility of a North Korean Collapse, RAND Corporation, 2013.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter