The current regional order and the balance of superpower influence in the Indo-Pacific region, particularly in Southeast Asia, are on the verge of a significant turning point.1 In Southeast Asia, where the United States and China have been competing for influence, the weakening confidence of Southeast Asian countries in the United States and the subsequent relative decline in American influence or leadership could disrupt the balance between the two powers. This shift could accelerate if the Trump administration returns to power in the 2024 U.S. presidential election. Even if the Democratic Party retains power, a similar outcome is likely, albeit at a slower pace, if the Biden administration’s weak engagement in Southeast Asia continues.

Southeast Asia holds a crucial key in the U.S.-China rivalry. If Southeast Asia falls under China’s sphere of influence, the United States risks losing not only its economic interests in the region but also a vital geopolitical strategic position connecting the Pacific and Indian Oceans. For China, securing support and influence in Southeast Asia, which it considers its backyard, and blocking U.S. access, are crucial. Southeast Asia is also important to South Korea, being the second-largest partner for trade and investment as well as a significant market for overseas construction and a focus area for South Korea’s development cooperation. For South Korea, facing the U.S.-China competition, it is essential to enhance its leverage with major powers and pursue strategic diversification. To this end, South Korea needs to strengthen strategic networks with regional organizations like ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) and Southeast Asian countries.

Since World War II, the strategic environment in Southeast Asia can be divided into three periods, during which Southeast Asia has undergone two significant turning points. During the U.S.-Soviet Cold War, Southeast Asian countries were divided into two blocs. Being part of a specific Cold War bloc meant securing a package of security and economic support from a great power.2 The balance of power between the U.S. and the Soviet Union provided regional countries with certain benefits and some degree of strategic autonomy. With the end of the Cold War, the influence of superpowers in Southeast Asia abruptly disappeared, creating a power vacuum. In this vacuum, regional multilateral cooperation initiatives led by ASEAN, such as the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) and ASEAN+3, emerged.

From the early 1990s until roughly 2010, the absence of great power influence in Southeast Asia ended with China’s rapid growth and the United States’ “Pivot to Asia” policy. After the global financial crisis in 2008, the U.S. quickly announced its pivot policy, marking a return to Asia, particularly to Southeast Asia.3 Following two decades of a power vacuum in the region, a new period of superpower competition, with the U.S. and China vying for influence in Southeast Asia, began to shape the region’s order. The balance of influence in Southeast Asia, established during this period, is facing challenges once again after a decade and a half.

There is growing concern that the previously balanced influence between the U.S. and China in Southeast Asia may be tipping toward one side. The strategic confidence Southeast Asian countries had in the United States is weakening. As speculation grows about the possible return of the Trump administration after the 2024 U.S. presidential election, there is an increasing possibility that the balance of influence between the superpowers in Southeast Asia could shift toward China. This shift would not necessarily be due to a Chinese victory or a decline in U.S. overall national power but because of the weakening U.S. engagement in the region. The Biden administration’s engagement in Southeast Asia has already diminished Southeast Asian countries’ confidence in the U.S. If Trump, who previously neglected Southeast Asia, returns, the regional countries might quickly lose faith in U.S. leadership due to neglect or ignorance of Southeast Asia by the United States.

If these projections come true, a hegemonic advantage in Southeast Asia might fall into China’s lap. This scenario could resemble the period after the Cold War when the U.S. left Southeast Asia and China was free to expand its influence in the region thanks to the vacuum left behind by the U.S. The same race will unfold again, but this time, China is likely to be an established power while the U.S. challenges the Chinese position, unlike what happened before.

These significant changes in the strategic environment have strategic implications for South Korea. A shift in the regional balance of influence suggests more fundamental changes for South Korea beyond the South Korea-U.S. alliance and Korean Peninsula issues. However, this risky situation could also present opportunities for South Korea. It provides space for South Korea to take the lead in fostering cooperation among middle powers in the region, to buttress the eroding balance of influence. Additionally, it could serve as a chance for South Korea to strengthen strategic cooperation and solidarity with Southeast Asian countries. These opportunities depend on how South Korea utilizes them with long-term regional strategies.

The U.S.-China Balance in Southeast Asia During the Biden Administration

The current strategic competition between the United States and China in Southeast Asia is asymmetric, particularly in geographical terms. China is an adjacent neighbor to the Southeast Asian region, whereas the United States is geographically distant. While China can exert military and economic influence directly in Southeast Asia, the United States’ engagement is often hindered by the geographical distance between Southeast Asia and the U.S. (the “tyranny of distance”).4 Since China’s rise and its competition with the U.S., Southeast Asia has viewed China’s ascent as both an economic opportunity and a potential security threat. To offset this, there has been a positive view of U.S. strategic and economic engagement in the region. The region has needed U.S. military involvement to balance China’s power and U.S. economic engagement as an alternative to becoming overly dependent on China’s economic strength. This balance of influence has long been a strategic norm in the region.

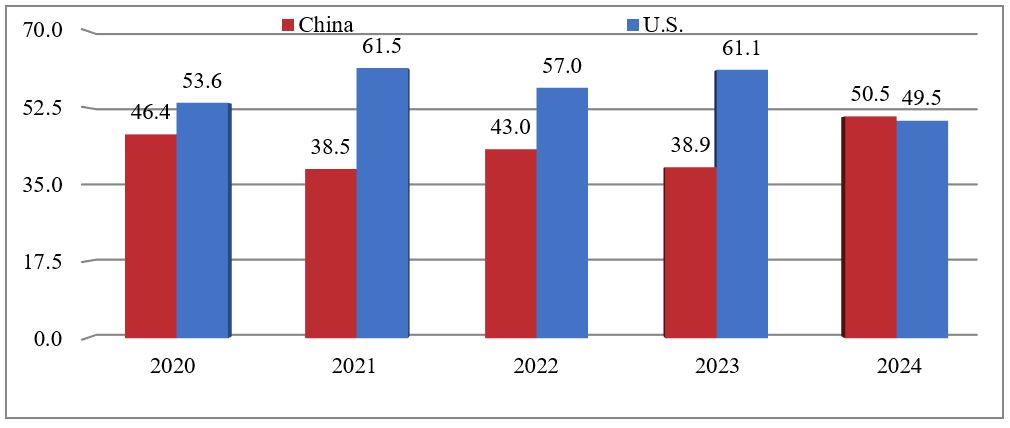

Figure 1. Which Should ASEAN Choose: The US or China? 5

Source: The State of Southeast Asia, 2020-2024

The results of a 2024 opinion survey conducted by the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore signal significant cracks in the balance of influence between the United States and China in Southeast Asia. As shown in Figure 1, the survey results from 2020 to 2024 indicate a shift. While the U.S. led China from 2020 to 2023, the 2024 survey results show the U.S. trailing China by a very narrow margin. The sudden shift from a comfortable U.S. lead in 2023 to a slight deficit behind China in 2024 suggests a potential collapse of the great power balance in the region. As mentioned earlier, the U.S.’s influence in Southeast Asia has a disadvantage compared to China’s due to geographical asymmetry. Therefore, the survey results prior to 2024, showing the U.S. ahead, could be interpreted as indicating a balance between the two powers. Extending this interpretation and considering the geographical separation, the 2024 results suggest that the U.S. is substantially trailing behind China.

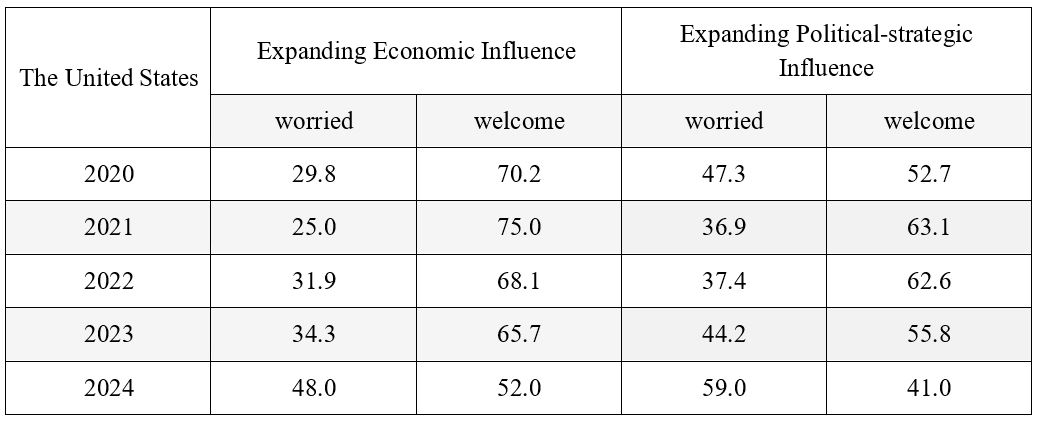

Table 1. ASEAN’s View on the Expansion of the U.S. Economic

and Political-Strategic Influence

Source: The State of Southeast Asia, 2020-2024

Furthermore, similar changes have been detected in surveys assessing the economic, political, and strategic influence of the United States and China in Southeast Asia. Concerns about the increase in U.S. economic influence have risen from 29.8% in 2020 to 25% in 2021, 31.9% in 2022, 34.3% in 2023, and 48% in 2024. On the other hand, positive evaluations of the expansion of U.S. economic power have decreased from 70.2% in 2020 to 52% in 2024. Concerns regarding U.S. political and strategic involvement also increased from 47.3% in 2020 to 59% in 2024, while positive evaluations of the expansion of U.S. political and strategic influence dropped from 52.7% in 2020 to 41% in 2024.

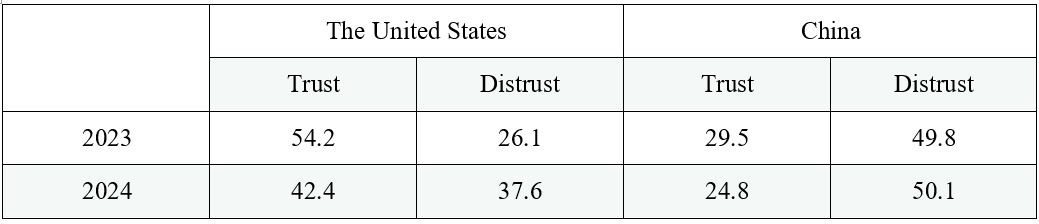

Table 2. Southeast Asia’s Strategic Trust in the United States and China

Source: The State of Southeast Asia, 2024 pp. 66-67.

Table 2 shows the trust levels in the United States and China as strategic partners and providers of regional security in Southeast Asia between 2023 and 2024. When comparing the two, Southeast Asia still shows higher strategic trust in the United States than in China. For China, the percentage of “distrust” significantly exceeds that of “trust” by more than double. In contrast, while still slightly higher, trust in the U.S. remains higher than distrust. However, a different picture emerges when examining the changes over time. Trust in the U.S. dropped significantly from 54.2% in 2023 to 42.4% in 2024. In 2024, the difference between distrust and trust was just over 5%. The perception of U.S. engagement in the region also declined, with the percentage of respondents noting a decrease (“decreased” or “greatly decreased”) rising from 25.7% in 2023 to 38.2% in 2024. Consequently, the response indicating an increase in engagement (“increased” or “greatly increased”) fell significantly from 39.4% in 2023 to 25.2% in 2024.6

These results indicate several key points: While the United States still leads China in Southeast Asia overall, the gap has narrowed significantly. Positive evaluations of the U.S. by Southeast Asian countries peaked in 2021 and have been steadily declining up to 2024. This means that the optimism seen in polls conducted in anticipation of President Biden’s first year in office has waned throughout his administration. However, China has not necessarily absorbed all the benefits from the United States’ decline, as distrust toward China among Southeast Asian countries has also significantly increased. In summary, considering the physical distance between the U.S. and Southeast Asia, the U.S. needs to maintain a certain lead over China to achieve a balance. However, the 2024 survey numbers indicate that the U.S. and China are at a similar level, suggesting that, in practical terms, China is ahead of the U.S. when accounting for the distance factor.

Projecting the Balance of Superpower Influence in Southeast Asia Post-2024 U.S. Election

The 2024 U.S. presidential election is only a few months away. Amid an unusually contentious race, there is even uncertainty about whether the two leading candidates will remain in the running. Assuming that the Democratic candidate and the Republican candidate, Donald Trump, continue to compete until the end, one of them will become the next U.S. president in 2025.7 For Southeast Asian countries hoping for a balance of influence between the U.S. and China, neither candidate brings promising news. U.S. engagement in Southeast Asia has already weakened significantly, signaling a decline in American leadership and a failure to counterbalance China’s influence in the region. If the next Democratic administration succeeds Biden and fails to deviate from existing Southeast Asia policy, U.S. leadership in the region will slowly but steadily weaken. If Trump is elected, U.S. leadership in Southeast Asia is likely to end swiftly and definitively.

The Biden administration, following the Trump administration’s abandonment of Southeast Asia, was met with Southeast Asian countries’ high expectations. In a late 2020 survey, 68.9% of Southeast Asians expressed optimism about increased U.S. engagement in the region under Biden, a stark contrast to the mere 9.9% positive response during the final year of the Trump administration, reflecting an almost 60-percentage-point increase.8 There was anticipation that the Biden administration, which advocated restoring alliances and “Building Back Better,” would implement a “Pivot 2.0” following Obama’s pivot policy. Indeed, the U.S. made some efforts, such as participating in the 2021 U.S.-ASEAN Summit online during the pandemic, hosting the first U.S.-ASEAN Special Summit in 2022, and establishing a comprehensive strategic partnership with ASEAN in the same year.

However, substantive and concrete involvement did not back up these high-level symbolic engagements. The Biden administration’s Indo-Pacific Strategy, announced in 2021, mentioned only Vietnam and Singapore as strategic partners, leaving out other countries entirely.9 Southeast Asian countries, or ASEAN, had no place in the strategic frameworks that garnered attention during the Biden administration, such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), AUKUS, and the South Korea-U.S.-Japan trilateral security cooperation. Instead, emphasis was placed on the United States’ traditional strong allies. The nuclear-powered submarines promised to Australia under AUKUS even drew backlash from Southeast Asian countries. Furthermore, the strengthening of strategic cooperation between the U.S., Japan, and the Philippines, especially from 2023 onwards, as they faced conflicts with China in the South China Sea, only exacerbated discord within ASEAN.10 As initiatives like the Quad and AUKUS were highlighted, ASEAN-led forums such as the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) and the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus (ADMM+) found their roles increasingly marginalized.

Economically, the Biden administration reinforced Trump’s approach of containing China. The Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) sought to establish an economic order to counter China. However, as the IPEF is not a trade agreement, it failed to provide access to the U.S. market, which Southeast Asian countries desired.11 Instead, the Biden administration emphasized reshoring and friend-shoring—as exemplified by the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS and Science Act—to compete with China in supply chains.12 This policy resulted in heightened U.S. protectionism, which further made U.S. market access difficult. Aggressive interest rate hikes aimed at addressing domestic economic issues in the U.S. led to currency instability for the Thai baht, Malaysian ringgit, and the Philippine peso; capital outflows from Southeast Asia; increased burdens of foreign debt repayment; and rising costs of importing capital goods.13

Under the Biden administration, the weakening of U.S. influence in Southeast Asia has manifested in two ways. First, the uncertainty of U.S. engagement with Southeast Asia, which has fluctuated since the Cold War, has continued under Biden. The cycles of engagement driven by U.S. needs during the Cold War, followed by disengagement for over twenty years in the post-Cold War period, re-engagement through the pivot under Obama, and then disengagement under Trump and Biden have gradually eroded Southeast Asian confidence in the U.S. commitment. Second, both the Trump and Biden administrations prioritized American interests over U.S. global and regional leadership, despite Biden’s emphasis on alliances. The Biden administration’s policies, aimed at competing with China and securing U.S. economic interests, were insufficient to demonstrate U.S. leadership capable of balancing China’s potential threat in the region. A Democratic administration succeeding Biden’s policy in late 2024 would likely mean a gradual decline in U.S. influence.

In contrast, if Trump were to be elected, it is predictable that his administration would show little interest in Southeast Asia. It is unlikely that the region, which received minimal attention during his first term, would suddenly become a major focus. Trump’s first-term Asia policy was characterized by a disregard for alliances, both in Asia and globally, with ASEAN and Southeast Asia receiving virtually no attention. For instance, during Trump’s first visit to the East Asia Summit (EAS) in the Philippines in 2017, he left the country before the summit began.14 In 2018, Vice President Mike Pence attended on his behalf, and in 2019, National Security Advisor Robert O’Brien represented the president at the meeting. While some Southeast Asian countries gained from the U.S.-China economic war, the overall impact was more detrimental than beneficial, posing significant strategic and economic risks to Southeast Asian countries. There seems to be little incentive for Trump to change this disregard for Southeast Asia in a potential second term. Experts in both the U.S. and Southeast Asia expect that if Trump were to return to office, his Southeast Asia policy would either replicate his first term or show even greater indifference.15

The doubts about U.S. leadership during Trump’s first term were further amplified under the Biden administration. Should Trump be re-elected, Southeast Asian countries would not just question but conclude the end of U.S. influence and leadership. Since the end of the Cold War, the U.S. has been inconsistent in its engagement with Southeast Asia, making America’s continued presence in the region one of the greatest strategic risks from the perspective of Southeast Asian countries.

Recently, instead of consistent engagement, the U.S. seems to be using Southeast Asia as a tool in its strategic competition with China. The economic instability resulting from U.S.-China competition, along with potential unintended military conflicts, such as one in the South China Sea, pose direct security risks to Southeast Asian countries. In this context, the collapse of U.S. leadership could decisively tilt the precarious balance of influence between China and the U.S. in Southeast Asia toward China. This shift would result not from China’s excellence but from the U.S.’s ineffectiveness, allowing China to outmaneuver the U.S. in the competition for regional influence.

Implications for South Korea’s Southeast Asia Strategy

The outcome of the U.S. presidential election is a major concern for South Korea because of its military alliance with the United States. Even if it is not led by Biden, the return of a Democratic administration could provide some continuity in South Korea-U.S. relations. On the other hand, a second Trump administration could mean a repetition or intensification of the pressures on allied countries and a transactional approach to foreign policy and strategic issues, as seen during Trump’s first term. These factors could pose risks to the South Korea-U.S. alliance. The South Korea-U.S. relationship inevitably has significant implications for inter-Korean relations and issues concerning the Korean Peninsula. Depending on the election outcome, significant resources will be allocated to assess its impact on the South Korea-U.S. alliance and the Korean Peninsula and to develop corresponding response strategies.

However, South Korea’s strategic considerations should not stop there. As mentioned earlier, the strategic situation in Southeast Asia, and more broadly in the Indo-Pacific region, could be significantly impacted by the U.S. election outcome, especially in terms of U.S. influence over developing countries, such as ASEAN countries. The weakening of U.S. regional leadership and influence could pose a major risk for South Korea. If China’s influence strengthens as U.S. engagement weakens across Southeast Asia and the broader region, the consequence could affect not just Southeast Asia but the entire Indo-Pacific order. The weakening of the liberal international order and the intensification of China’s assertiveness could greatly constrain South Korea’s influence as a middle power. Moreover, the geopolitical shift toward greater Chinese influence could negatively impact South Korea’s economic and strategic interests in Southeast Asia.

South Korea, however, may also find opportunities in these risky circumstances. The potential collapse of the balance of influence among major powers due to weakened U.S. influence presents a risk, but it could also highlight the role of regional middle powers in restoring this balance. Cooperation and solidarity among regional middle powers may be more critical than ever in maintaining a balance against China in the Indo-Pacific or, more narrowly, in Southeast Asia. During Trump’s first term, the U.S. isolationism and self-centered policies led to discussions about middle powers stepping in to uphold the liberal order left vacant by the U.S.16 This role for middle powers—or middle power solidarity—may be needed once again.

This situation offers South Korea an opportunity to lead discussions on how to shape the future regional order and maintain a balance against China, in coordination with other middle powers such as Australia, Japan, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Singapore. What was previously considered an alternative or supplementary strategy—strategic solidarity among regional middle powers—could become a central strategy. South Korea can take the initiative in fostering minilateral cooperation, bringing regional middle powers together, and setting agendas for cooperation. It can revive the Korea-Indonesia-Australia (KIA) cooperation as a forum for strategic discussions or propose new initiatives like a Southeast Asia-Oceania-Northeast Asia (SONA) strategic dialogue.17 The key lies in anticipating and setting the agenda for action in response to strategic changes due to the U.S. election; discussing regional order, and the balance of power among regional superpowers; and actively involving partner middle powers.

The post-U.S. election regional situation can be an opportunity for South Korea to strengthen strategic cooperation with ASEAN and Southeast Asian countries. There is already discussion among Southeast Asian countries about the limitations of U.S. engagement, weakened U.S. leadership, and instability in regional power balances. As a result, there is growing interest in building a strategic coalition with a third power, beyond the major powers of the U.S. and China.18 South Korea has long been focused on the Korean Peninsula for its strategic and security concerns, but given its increased national power, it can no longer limit itself to a narrow diplomatic and security agenda. There is an increasing external demand for South Korea to play a greater role.

Coincidentally, South Korea’s “Korea-ASEAN Solidarity Initiative” (KASI) also emphasizes strategic cooperation with Southeast Asian countries. The weakening of U.S. engagement in the region provides an environment conducive to more in-depth and substantive discussions between South Korea and ASEAN on regional strategic situations, the weakening of U.S. leadership, and the balance of influence issues in the region. South Korea should seize this risk-disguised opportunity to strengthen strategic cooperation with ASEAN, correcting the previous focus solely on major powers like the U.S. and China, and building its own independent strategic and autonomous network. As with middle power cooperation, if South Korea shows leadership by assessing situations, setting agendas, and actively proposing dialogue and practical cooperation with ASEAN counterparts, it can deepen South Korea-ASEAN relations and enhance South Korea’s strategic presence in the region, achieving dual benefits.

This article is an English Summary of Asan Issue Brief (2024-20).

(‘2024년 미국 대선 이후 동남아에서 강대국 영향력 균형의 향배’, https://www.asaninst.org/?p=94998)

- 1. In this article, the concept of “balance of influence” is used instead of the commonly used concepts of “balance of power” or “balance of forces” between the U.S. and China. While the perspective of a balance of power or forces is understood to mean a military standoff between the U.S. and China, the balance of influence refers to how much support the U.S. and China receive among Southeast Asian countries, the extent of their leadership, and how much confidence and trust the regional countries have in these two superpowers.

- 2. Toby Carroll. 2020. “The Political Economy of Southeast Asia’s Development from Independence to Hyperglobalisation.” in Toby Carroll, Shahar Hameiri and Lee Jones eds. The Political Economy of Southeast Asia: Politics and Uneven Development under Hyperglobalisation (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan). p. 45-51.

- 3. Kurt M. Campbell. 2016. The Pivot: The Future of American Statecraft in Asia (New York: Twelve Books). p. 261-264.

- 4. David Shambaugh. 2021. Where Great Powers Meet: America and China in Southeast Asia (New York: Oxford University Press). p. 101-103.

- 5. The original questionnaire was “If ASEAN were forced to align itself with one of the strategic rivals, which should it choose?”.

- 6. Seah, S. et al., 2024. The State of Southeast Asia: 2024 Survey Report (Singapore: ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute). p. 53.

- 7. Just before the publication of this article, on July 22, 2024 (Korean time), President Biden announced that he would no longer be running for office and expressed his support for Vice President Kamala Harris. At the time of writing, it is still uncertain who will ultimately become the Democratic presidential candidate.

- 8. From The State of Southeast Asia, 2020 and 2021.

- 9. White House. 2022. “Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States.” February (https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/U.S.-Indo-Pacific-Strategy.pdf).

- 10. Premesha Saha. 2023. “Great power competition raises concerns within the ASEAN.” ORF. August 16 (https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/great-power-competition-raises-concerns-within-the-asean); Richard Heydarian. 2023. “Marcos’ courting of U.S. support is unsettling his ASEAN neighbors.” Nikkei Asia. December 1.

- 11. Emily Benson and Aidan Arasasingham. 2022. “The IPEF gains momentum but lacks market access.” East Asia Forum. June 30.

- 12. Jayant Menon. 2024. “The export-led model is evolving, not dying.” East Asia Forum. March 23.

- 13. Dylan Loh. 2022. “ASEAN banks face sharper debt risks as interest rates rise.” Nikkei Asia. November 11; Jack Stone Truitt. 2023. “India and ASEAN growth to slow in 2023 as interest rates rise: IMF.” Nikkei Asia. January 31.

- 14. Ian Storey and Malcolm Cook. 2020. “The Trump Administration and Southeast Asia: Half-time or Game Over?” ISEAS Perspectives 112. October 7.

- 15. Joshua Kurlantzick. 2024. “What a second Trump term could mean for Southeast Asia.” The Japan Times. May 8; Neo Chai Chin. 2024. “Analysis: As chances of a Trump 2.0 presidency shoot up, how ready are Southeast Asian states?” Channel News Asia. July 18; Hunter Marston. 2024. “Southeast Asia Wants U.S.-China Conflict to Stay Lukewarm.” Foreign Policy. July 3; Ford Hart. 2024. “Southeast Asia and Trump 2.0(?): Agency Amid Anxiety.” Fulcrum. June 5.

- 16. Roland Paris. 2019. “Can Middle Powers Save the Liberal World Order?” Chatham House Briefing. June18; Umut Aydin. 2021. “Emerging middle powers and the liberal international order.” International Affairs 97:5..

- 17. Jonas Parello-Plesner. 2009. “KIA – Asia’s middle powers on the rise?” East Asia Forum. August 10.

- 18. Benjamin Ho. 2024. “Bound to Lead: US-China Relations and the Future of Global Leadership.” IDSS Paper IP24046. May 1. Furthermore, it is important to note that in the “State of Southeast Asia” survey, there has been a consistently stronger preference for aligning with a third power rather than being forced to choose between the U.S. and China as a way to manage the strategic risks arising from U.S.-China competition.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter