“We come from the desert. We have been living on camel milk and dates. And we can easily go back and live in the desert again.” – King Faisal to Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s threat of military action during the Oil Embargo of 19731

“Oil is the Devil’s Excrement…. Ten years from now, twenty years from now, you will see. Oil will bring us ruin.” – Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonzo, Venezuelan politician and co-founder of OPEC2

Introduction

Saudi Arabia (officially ‘the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’, KSA) stands at the proverbial fork in the road. For much of the last 25 years, it has been the world’s leading oil producer.3

However, prices have fallen from a peak of over $100 in 2013 to less than half that now. The global economy appears to be moving away from this geopolitically suspect and environmentally devastating addiction to oil. The Saudis are thus confronted with a difficult choice.

The 31-year-old Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s (MBS) is the man who seeks to wean Saudi Arabia away from its dependence on oil to a more diversified economic base. Under his watch, the Saudi government turned to the management consultancy McKinsey & Company for analysis and recommendations. Their work formed the basis for Vision 2030, a blueprint that will allow Saudi’s to prosper in a post-oil future. While offering short-term measures to cut state spending, Vision 2030 lacks basic details on how Saudi Arabia should and need to plan for a post-oil future. Its main focus is on public investment, privatization, and achieving fiscal balance.

In the short-run, the Saudi state aims to achieve fiscal balance through cuts and privatizations. In the long-run, McKinsey and the Saudi state envision the expansion of privatization of public services and massive investment in infrastructure projects as keys to a post-oil future.

Rather than creating jobs, the admixture of public works projects and privatization of large parts of the public sector will destroy jobs, resulting in hardship for ordinary Saudis. The public sector is massive; over 65% of Saudi workers are employed by the state. Privatization of public services usually involves streamlining (i.e. layoffs). Privatization is a measure to cut jobs, cut state outlays, and pave the way for consumer to pay directly for services. These measures will unlikely be sufficient to spur a genuine post-oil diversification.

The other major part of the Vision, massive public works and investment by the state, will do little to tackle Saudi Arabia’s rudimentary private sector problem. The private sector is heavily dependent on the state. And the Vision has no real solutions to this problem except to hope that from privatization a vibrant private sector will spring into life.

The Vision will buy Saudi Arabia some fiscal breathing space, allow it to borrow more money, and gradually shrink the size of its bloated state. But, the public works projects that are currently underway will likely fail to transform the KSA. The problems are systemic and fundamental. The solutions must be too.

Swollen state, dependent society

Petrodollars have financed the Saudi’s generous welfare structure and development programs.4The Saudi state’s lavish benefits include high paying public sector jobs with lifetime job security. The average private sector pay for Saudis is only 60% of public sector wages.5The state also spends more than 4% of total GDP on energy and water subsidies, another form of regressive welfare.6Rich households tend to have more appliances, larger houses, and larger cars. They will disproportionately benefit from energy and water subsidies.

It does not end there. The private sector is heavily dependent on oil revenues. Over the last decade, the state has gone on an investment spending spree, with contracts involving private sector contractors totalling $700 billion in 2013 prices (around 11% of GDP).7Such contracts have been crucial to sustaining private sector growth. Indeed, as political economist Steffen Hertog has shown,8private sector investment and growth closely tracks growth in the public sector. This heavy reliance on government spending makes the Saudi private sector qualitatively different from private sectors in other developed countries. The Saudi private sector is staffed almost entirely by foreign workers, a third of the total population. But these foreign workers, the backbone of Saudi’s private sector, are merely an afterthought to the larger plans of Saudi leaders and McKinsey consultants. That is a fatal flaw.

The Saudi government today spends 45% of its budget on public sector payroll (around 15% of GDP).9Public sector employment growth averaged 6% between 2001 and 2012,10and employment within the public sector continued to expand in 2014 and 2015).11 This is fiscally unsustainable.

Nearly 67% of Saudi nationals work in the public sector. While an impressively high number of working age males (78%) are in the workforce, only about 20% of Saudi women are employed.12 Total unemployment is an impressively low 5.6%, some 11.5% of Saudi nationals are unemployed. About 45% of the population is under the age of 25,13with youth unemployment estimated to be around 31%.14 This indicates that the existing dependence on oil has not created jobs for young people, and that even if oil prices were to rise, a fresh approach would be needed.

The Mirage of Vision 2030

Western management consultants appear to have inordinate influence over Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States.15 Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 was unveiled in 2016. Bahrain (in 2008) and the UAE (in 2008) had their own Economic Vision 2030s,16and Oman had its ‘Vision 2020’.17 All these reports share the following concepts – fiscal tightening, reform of energy and water subsidies, privatization, and anticipation of foreign investment – that bear all the hallmarks of a McKinsey-inspired plan.

In December 2015, the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI), the independent research arm of the consultancy McKinsey & Company, released a report entitled “Saudi Arabia Beyond Oil: The Investment and Productivity Transformation”.18 The report’s goal was to outline what Saudi Arabia needed to do to remain affluent in a world of shrinking oil revenues.

In its ‘full potential’ scenario, Saudi GDP would double between 2014 and 2030, household income would rise by 60% (it is projected to fall by 20% under the status quo), and unemployment is to decline to 7%.19

To deal with Saudi Arabia’s bloated state sector, MGI calls for a 40% cut in public sector salaries by 2030.20 In a country where nearly 70% of employed Saudi nationals work in the public sector, this plan is all but politically impossible. The expectation is for more Saudis to find better work in the private sector.21

In this regard, tourism and the retail/wholesale sectors are touted as the panacea to Saudi Arabia’s post-oil growth. The two sectors are expected to provide as much as one-third of growth in GDP and employment. The report calls for an ambitious target of an 11% annual growth in tourism-related industries that would lead to more employment of Saudi nationals.22

The problem is that tourism and the retail/wholesale sector are dominated by low-paid, foreign workers. Thus, it is unlikely that upward of 1.5 million Saudis, many of them used to comfortable jobs in the public sector or generous government scholarships, would be eager to find gainful employment in these parts of the private sector unless their wage structure was radically transformed. Foreign nationals have served as substitute for a non-existent native working class. They have performed for wages the typical Saudi would balk at.23 The government’s major plan for foreign nationals (who constitute third of the total population) is to tap them as a source of revenue under the so-called ‘expat levy’. Yet the MGI report treats foreign workers just as the Saudi state always has – as a prop for Saudi economic and social development that would never be fully integrated into Saudi society.

The MGI report also singles out other sectors for growth and Saudi jobs such as mining, advanced manufacturing and construction. The projected potential growth rates in these sectors are grossly unrealistic. For example, the report suggests that advanced manufacturing will grow at a 22% rate. Once again, regardless of whether investment in technology and more efficient organizations lead to explosive growth, foreign workers are likely to make up the bulk of the workforce because they are cheaper to hire and easier to fire. MGI’s claim that over 50% of job growth in the private sector would go to Saudi nationals is implausible: even if something approximating these growth level were to be achieved.

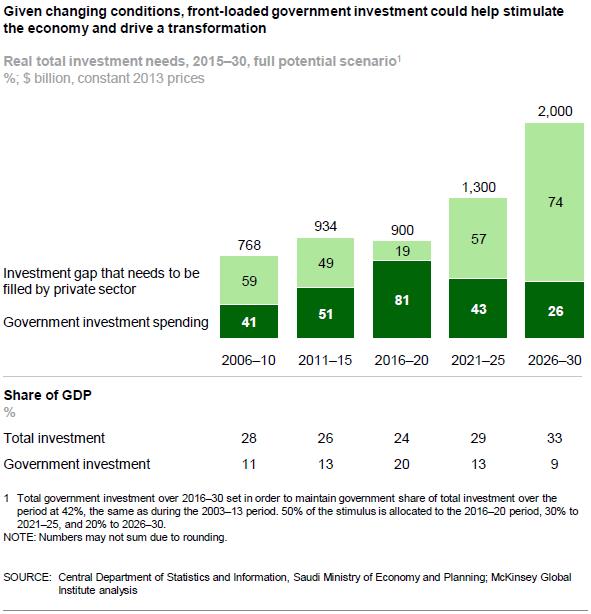

Since McKinsey counts the Saudi government as a major client in the region, the group has little incentive to overestimate costs. Thus, the $4 trillion price tag that MGI projects – which represents 620% of annual GDP (in current prices) as of 2016 – should be taken seriously as an indicator of how much money is needed to transform the Kingdom (see <Chart 1> below). The belief is that, after an initial flurry of public investment, most investment over the next decade and a half will come from the private sector, and be in the non-oil sector.

<Chart 1> McKinsey Global Institute’s numerical breakdown of Saudi’s optimal investment strategy24

Most investment up to now has been concentrated and funded by oil, with the majority of 2003-2013 investment going into the petrochemicals sector (56% of total).25 This is the only sector where Saudi has competitive advantage; it has no such proven advantage in other sectors. Aside from the oil sector, Saudi Arabia is essentially a high cost, low productivity economy. Even in their own country, Saudi workers are uncompetitive when compared to foreign workers. The question naturally arises – how can it be possible then to encourage large amounts of investment in these private, non-competitive sectors?

Ending petro-welfare through public investment?

The optimism of the MGI report was followed by the launch of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 (released in 2016). Improving the government’s balance sheet and diversifying the economy away from oil were the two main goals.

Reform of water and energy subsidies is a key part of achieving short-term fiscal sustainability. The plans to bring energy and water prices in line with prevailing market rates would indicate an end to the existing petro-state welfare regime in which residents of the Kingdom benefit from massive government subsidies. The Vision predicts that savings from these reforms would come to about 8% of the current GDP.26

Indeed, fiscal balancing is at the center of the Vision. A wide range of tax increases (VAT, expat levy) and cuts to government expenditure are suggested. Combined with a means-tested allowance for Saudi families, these measures favor poorer households.27 The aim is to redirect government welfare toward those actually in need – but only as long as they are Saudi nationals. This does not apply to foreign workers who are in much more need of such benefits.

What is far less clear but far more important to the sustainability of Saudi Arabia is diversification. This strategy involves a heavy mix of government investment and privatization. The Vision seeks various plans for the private provision of government services (largely in health and education), and privatization plans for hospitals, school construction, water desalination and segments of the electrical industry.28

The privatization plan most widely discussed involves the plan to sell 5% of Saudi ARAMCO in an IPO that would be worth $100 billion. This would kick start an investment boom in the country led by the Saudi government’s sovereign wealth fund (the Public Investment Fund).

The hope is that privatization will spur foreign investment and economic growth while reducing government liabilities. Such moves often prove highly controversial with service users who often have to pay higher fees. Privatization will also probably involve massive layoffs in the affected sectors – with grave political consequences. Many parts of the Saudi state sector are inefficient and overmanned. To become efficient and profitable as private enterprises will almost certainly involve layoffs, and use of better (labour-saving technologies). This will involve job losses now and fewer hiring in the future. Will those who lose their jobs, and those who do not have job opportunities accept their fate? Or will they openly begin to express their dissatisfaction with the closed, authoritarian monarchy that rules over them?

Saudi Arabia holds significant foreign reserves (approximately $500 billion). But will they be released to underwrite the transformation?29 The Kingdom clearly is investing sizable amounts in a multi-pronged development strategy that includes high tech industries, entertainment, education, tourism, logistics and finance. The frontloading of state investment that MGI calls for has been put into effect in seven flagship construction projects.30 However booms in infrastructure spending do not address the fundamental economic problem: Saudi Arabia remains a high cost, low productivity society. Such manpower-heavy projects will barely sustain a private sector largely dependent on state contracts and foreign workers until the state has no more money to dispense.

The Saudi state anticipates that real estate development and new infrastructure will generate growth. But the high cost of doing business in the country will likely scare off most foreign investment. Local private investment will hold only so long as the state has money to dispense. With revenues in decline, the state will soon have to start cutting, and the local private sector will likely follow suit. This will then lead to welfare cuts that Saudis have never experienced. What will they do? Join the private workforce and work for far less than their parents? Or might they begin to question the legitimacy of the House of Saud?

Conclusion

The transformation of Saudi Arabia is likely to be painful and protracted precisely because, despite all the bells and whistles of a consultant’s report, the reality is that Saudi Arabia is a high cost, low productivity country. Infrastructure spending will keep the economy stable in the short-run, but is unlikely to promote long-term growth.

The drive for efficiency in the public sector would require wage cuts that have already been largely scaled back due to political concerns.31 Plans for privatization will result in a series of one-time windfalls for the Saudi state. These privatizations will increase profits but likely lead to job losses. But after the money from privatization is spent, the same problem will remain. Eventual cut in infrastructure spending will lead to less, not more, jobs in the domestic private sector. If the experience of transition away from unsustainable statism in other countries is an indicator, the transition will be accompanied by a great deal of economic and social pain that may prove politically destabilizing.

Transforming the role of the state and creating a vibrant market sector has occurred in two kinds of countries in the last 30 years. Countries that started poor, like China and Vietnam which had yet to undergo an industrial revolution, introduced market mechanisms gradually, amidst the continuance of the political status quo.32 By contrast, industrialized countries, including those with substantial oil revenues like the Soviet Union, decided that mass restructuring of the entire economy were necessary because industries were overmanned, archaic production methods were used, and profits were not generated.

The ruling Saudi elite would clearly like to take the route that China took: maintaining their grip on power while presiding over a prolonged period of economic expansion. The MGI benchmarks countries that have proven successful in transitioning away from resource dependence and toward more vibrant tourist and manufacturing industries.33 But even with massive investment in productivity boosting technologies, Saudi Arabia still faces the unrelenting fact that its private sector is heavily dependent on poorly paid foreign workers and massive state investment. Secure white-collar work is unlikely to be in plentiful supply after the dust from the investment boom has settled.

In a world where the supply of jobs is set to shrink, investment in Saudi Arabia may not make sense for many global investors eying other potential logistics and financial hubs, or potential tourist developments. The Saudi consumer looks like they will be hit with years of austerity. The workforce expects high wages. There are many attractive alternatives in Asia and increasing Africa with cheaper, better trained workers.

Saudi Arabia may start to go the way of other Arab states when oil stops paying: economic decline and even possibly social collapse. Recent reports indicate that the Saudi government has begun to backtrack and scale back its plans. The Vision was ambitious and vague to begin with. Now it seems the plan in present form will not be implemented because of concerns about its potential socioeconomic and political consequences. The Saudi state is fast running out of time to affect an economic transformation, and avert a potential socioeconomic catastrophe.

* This study was supervised by Dr. Kim Jinwoo, Director, Office of Strategy and Analysis.

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter