Unknown Horror or Deliberate Indifference? A Comparative Analysis of Human Rights Violations in North Korea and Syria.

North Korea and Syria are currently the only two countries in the world that are the subject of United Nations (UN) Commission of Inquiry (COI) investigations into their human rights records. Traditionally, the UN has only commissioned such inquiries in the event of civil war. Yet the new COI report on North Korea released on February 2014 and the first two COI reports on Syria covering March 2011-February 2012 were conducted in the absence of internal armed conflict. Furthermore, both countries share a number of attributes in terms of hereditary successive structure, the possession of weapons of mass destruction (WMD), and international backers that makes a comparative analysis compelling.

This paper compares the human rights violations and crimes against humanity in North Korea and Syria as described in the COI reports. It finds that the consistency, purpose, and scope of human rights violations in North Korea are worse than those during the early stages of the Syrian uprising before the situation deteriorated into a civil war. However, unlike the case of Syria, not a single US Presidential Executive Order, EU Council Regulation, or UN Security Council Resolution has dealt with human rights violations in North Korea. This disparity is due to two reasons. First, Syria, as a country in the Middle East, is more strategically important to the US and EU than North Korea given its impact on oil resources, Islamic extremism, and the defense of allies in the region. Second, North Korea, as an extraordinarily secretive country, is less exposed to the outside world than Syria which is more connected via trade, travel, and NGO activities.

We find that:

1. The North Korean regime is a more persistent violator of human rights than the Syrian regime. Data from Freedom House shows that the political rights and civil liberties situation in North Korea has not changed once over the past forty years, whereas Syria has experienced brief periods of reforms in the 1970s and mid 2000s.

2. The North Korean regime seeks total mass subjugation in a systematic way whereas the Syrian regime seeks elite protection through fragmented institutions. The subjugation of the population in North Korea is carried out through the systematic use of terror by institutions operating under the direct supervision of Kim Jong-un. In Syria, on the other hand, the regime seeks to protect itself from the population through a range of loose institutions under the somewhat vague chains of command.

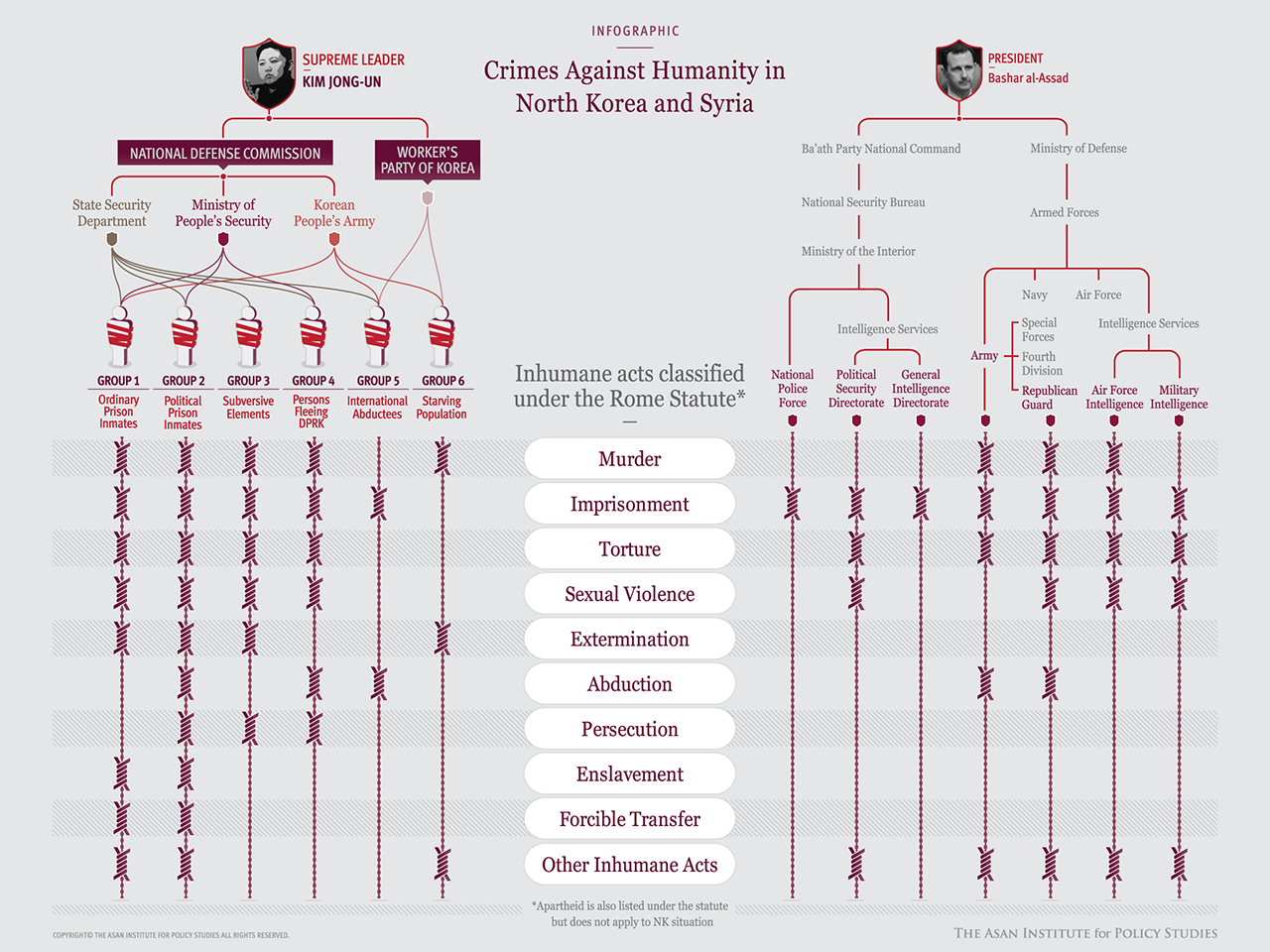

3. More crimes against humanity have been committed in North Korea than Syria. North Korea commits every crime against humanity that article 7 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court defines, including extermination, enslavement, persecution, and forcible transfers of population. Yet, Syria violates only six counts.

4. The international community focuses more on the human rights violations in Syria despite the more institutionalized terror in North Korea. Less attention of the international community to human rights in North Korea is because of North Korea’s lower geo-strategic importance than the Middle East and its isolation from the outside world. Surveys show that experts have been aware of the more deplorable human rights situation in North Korea and lower international focus on the country.

Worst of the Worst: North Korean and Syrian Regime Parallels

While past UN COI reports have investigated human rights violations in the midst of “non-international armed conflict,” the COI on North Korea (A/HRC/25/CRP.1) and the first two COIs on Syria (A/HRC/S-17/2/Add.1 and A/HRC/19/69) are unique in that they examine violations and crimes taking place in peacetime. Even though the situation in Syria subsequently deteriorated into a civil war by July 2012, the first two reports of the UN COI on Syria released on December 2, 2011 and March 12, 2012 were conducted at a time when the intensity of the conflict as well as the organizational capabilities of anti-government forces had not yet crossed the threshold. That is, the regime of Bashar Al-Assad was responding to largely peaceful demonstrations rather than an organized armed rebellion.

North Korea and Syria share a number of similarities that make a comparative study useful. First, both countries are hereditary dynasties in which power has been successfully handed down from father to son. Decades of purges by leaders in the countries have removed all potential non-familial challengers to the leadership position. It is unfathomable to imagine a North Korea or Syria without somebody named Kim or Assad at the helm. Second, the two countries are socialist republics whose foundations are a combination of socialism and ethnic nationalism. Their legitimacy is thus rooted in their defense of the socialist revolution as well as Korean or pan-Arab identity. In North Korea, this expresses itself in a fiercely anti-imperialist independence while in Syria, the regime lays claim to leading the struggle against Israel and upholding the Palestinian cause.

Third, the core constituency upon which the leader depends comprises only a tiny minority of the overall population. The privileged citizens of Pyongyang form the backbone of the North Korean regime while in Syria it is the Alawite religious community to which the Assad family belongs that has staunchly defended the regime. Fourth, regime security is guaranteed through an unwaveringly loyal parallel military. Though both countries have among the largest conscript armies in the world, they also have highly-trained, well-equipped forces ready to put down any coup attempts or rebellions.

Table 1. Regime Parallels between North Korea and Syria

Internationally, North Korea and Syria also share important characteristics. Both are known to have cooperated extensively in developing large arsenals of WMD. While Syria’s North Korean-built nuclear reactor was successfully destroyed in 2007, the 2013 Ghouta chemical gas attack in Syria demonstrates the ongoing threat posed by both regimes’ chemical and biological weapons. In addition, both countries are also important allies of Russia and China, who have shielded their human rights records from international scrutiny by vetoing UN Security Council resolutions targeting either country.

While Syria is thus one of the few countries that is comparable to North Korea in terms of power configurations, they have been different in how they abuse and terrorize their populations. This paper identifies three key differences between the two countries in their handling of human rights in terms of uniformity, purpose, and scope. It further examines why North Korea’s human rights situation receives less attention than Syria’s.

The North Korean Regime is a More Constant Violator of Human Rights than the Syrian Regime

Since North Korea was created in 1945 and Syria won independence from France in 1946, both countries have consistently ranked among the worst violators of political rights and civil liberties in the world. Data from Freedom House, however, shows that North Korea has historically been the worst violator of human rights anywhere in the world on a level that not even Syria comes close to paralleling.

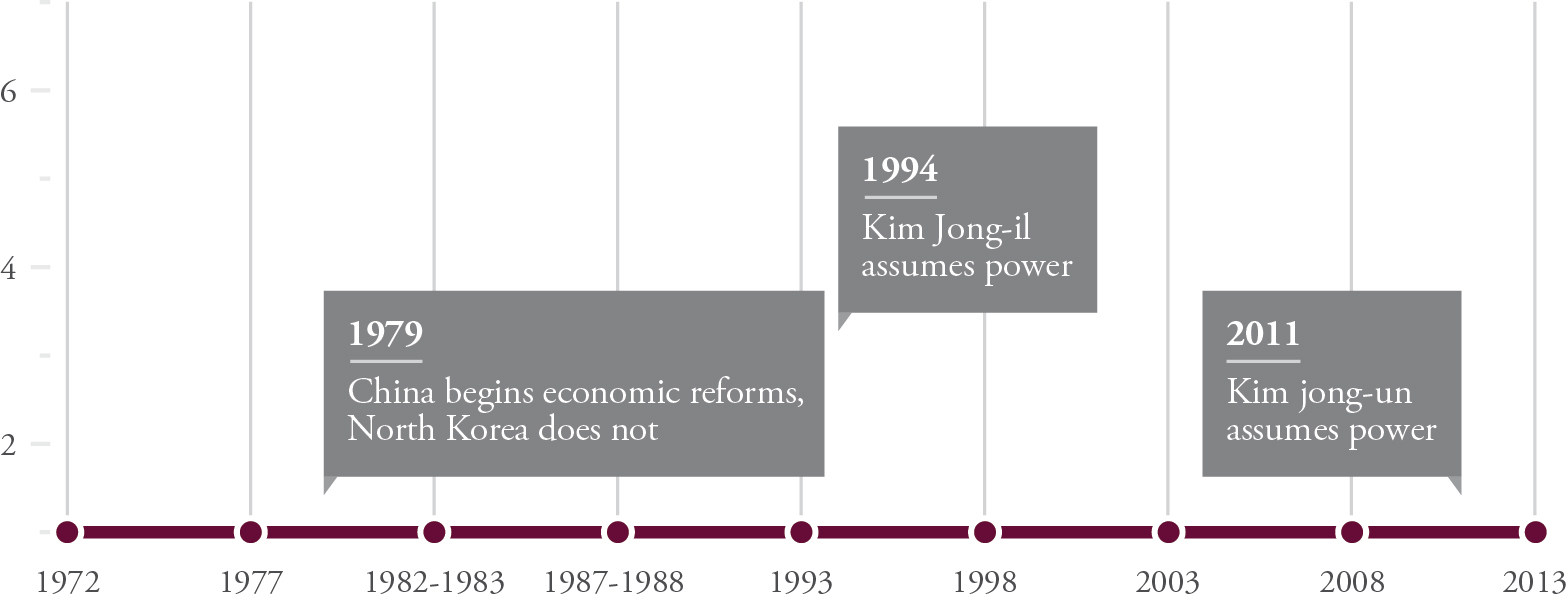

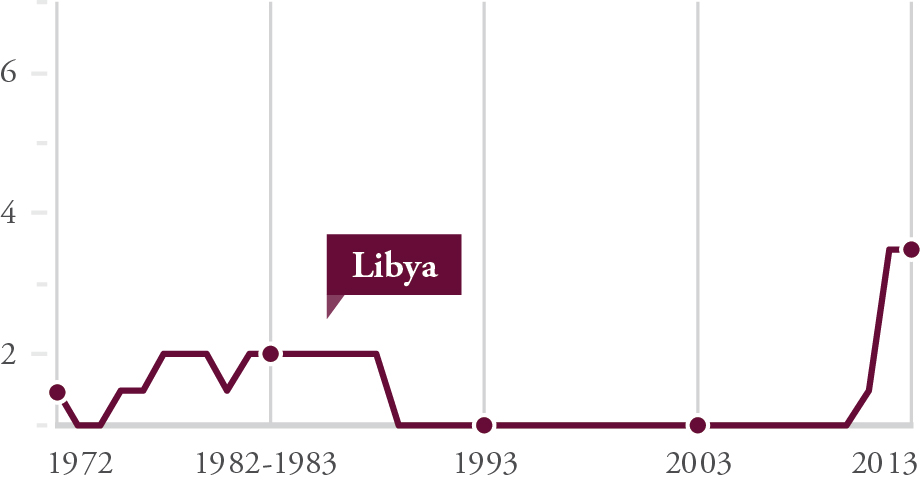

First, North Korea has shown no changes in terms of political rights and civil liberties since Freedom House began the Freedom in the World index in 1972 [see Figure 1]. The two cases of hereditary succession in 1994 and 2011, which usually produce some degree of change as a new ruler attempts to win support and introduce modest reforms, did not produce even a slight variation in North Korea’s freedom rankings.

Figure 1. Freedom Rankings for North Korea (1972-2013)

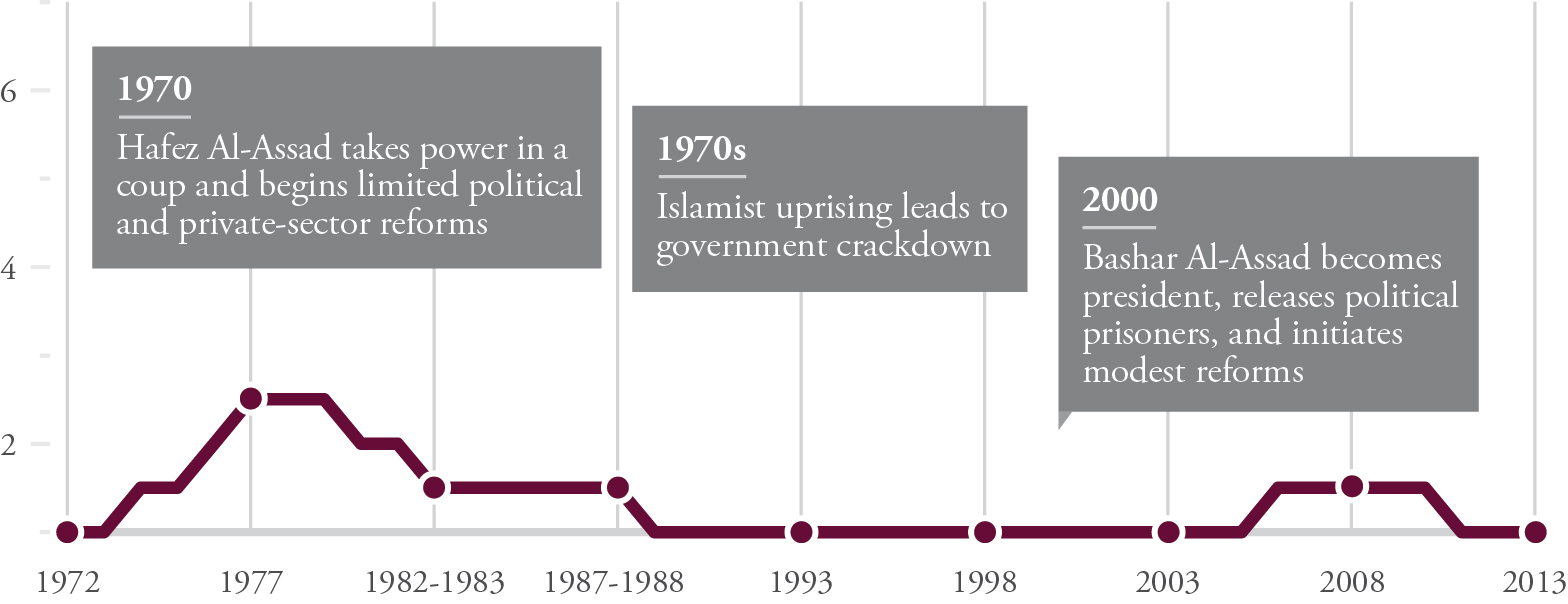

In contrast, Figure 2 shows some changes in political rights and civil liberties in Syria over the forty-one-year time frame. The first took place following the 1970 coup by Hafez Al-Assad, which came after a decade of political upheaval and successive coups in Syria. Once he took power, Hafez Al-Assad instituted modest private sector reforms and reduced the state’s presence in the economic sphere. Those reforms, however, were soon eclipsed by the government’s brutal suppression of an Islamist uprising in the 1970s, ending in the 1982 Hama Massacre against the Muslim Brotherhood. In 2000, with the inauguration of Bashar Al-Assad as president, there was yet another period of political reforms as he released political prisoners, enforced religious pluralism, and shunned much of the personality cult that his father had cultivated.

Figure 2. Freedom Rankings for Syria (1972-2013)

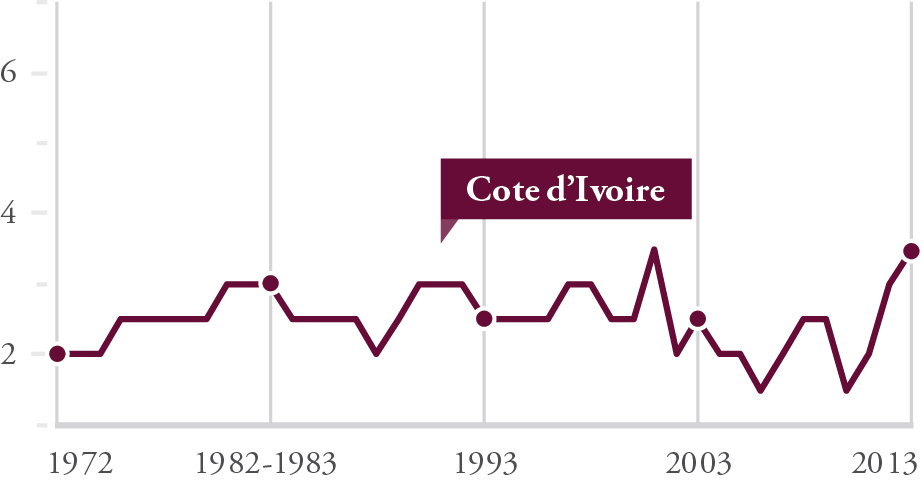

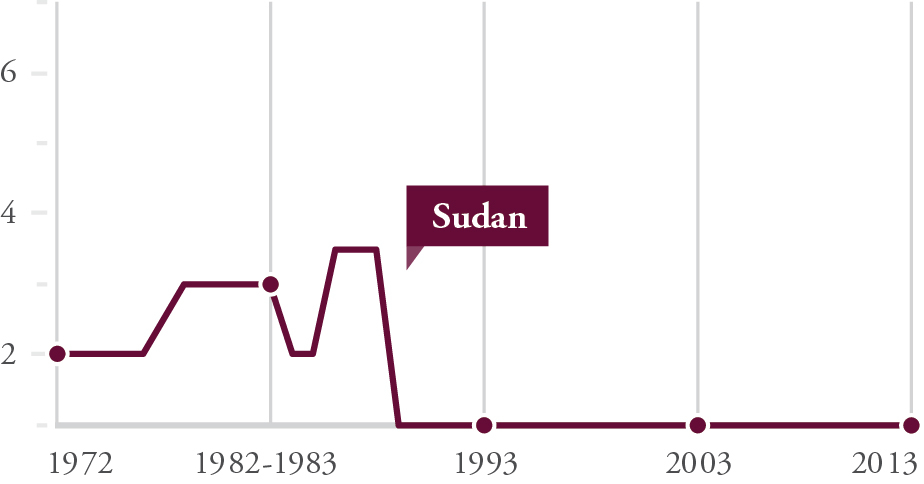

Second, even when compared with other countries that have been investigated by the UN Human Rights Council, North Korea remains unique in its uniformity of terror, as we can see in Figure 3. Cote d’Ivoire experienced two civil wars in 2002 and 2011, and Sudan became an autocratic regime following the 1989 coup by Omar al-Bashir. Libya was ruled by Muammar Qadhafi from 1969 until his ouster in the 2011 Libyan civil war. Yet, in all three cases, there were periods of political and economic reforms, however limited, during the 1970s and 1980s. Indeed, North Korea’s freedom rankings are worse than most countries in civil war.

Figure 3. Freedom Rankings for Recent UN COI Countries

In fact, the Syrian government has at least tried to maintain a veneer of respectability by acknowledging that human rights violations are taking place within its borders and that the state bears some responsibility for these actions. On March 31, 2011, the Syrian government established the National Independent Legal Commission to investigate over 4,000 cases where crimes were suspected to have occurred in the context of the crisis. In Legislative Decrees 34, 61, and 72, the regime also implemented amnesties for political prisoners and declared that it had released 10,433 people from detention on September 2, 2011. Such actions were likely intended to conceal the crimes being committed given that military and security forces enjoy immunity from prosecution under Decrees 14/1969 and 69/2008. Nonetheless, they are illustrative of the fact that the regime is forced to respond to such accusations and justify its actions. In contrast, North Korea has vehemently denied the findings of the UN COI claiming that there are no human rights violations taking place inside the country today.

The Totalitarian North Korean Regime Seeks Mass Subjugation While the Authoritarian Syrian Regime Seeks Elite Protection

An important difference in the human rights violations between the two regimes is the aims and institutional responsibility for human rights violations. In North Korea, Kim Jong-un directly dictates key institutions through the National Defense Commission in order to maintain strict control over its population, often including even high-level officials. In Syria, however, institutions are set up to prevent potential challenges to the Assad family through scattered organizations rather than to subjugate the entire population.

The various institutions and agencies responsible for committing human rights violations also differ considerably in terms of organizational efficiency and chain of command. This, indeed, reflects to what degree crimes are planned and carried out by the state. The shorter the operational chain of command between perpetrating institutions and the executive branch, the more likely that crimes are being directly ordered by the supreme leader or president.

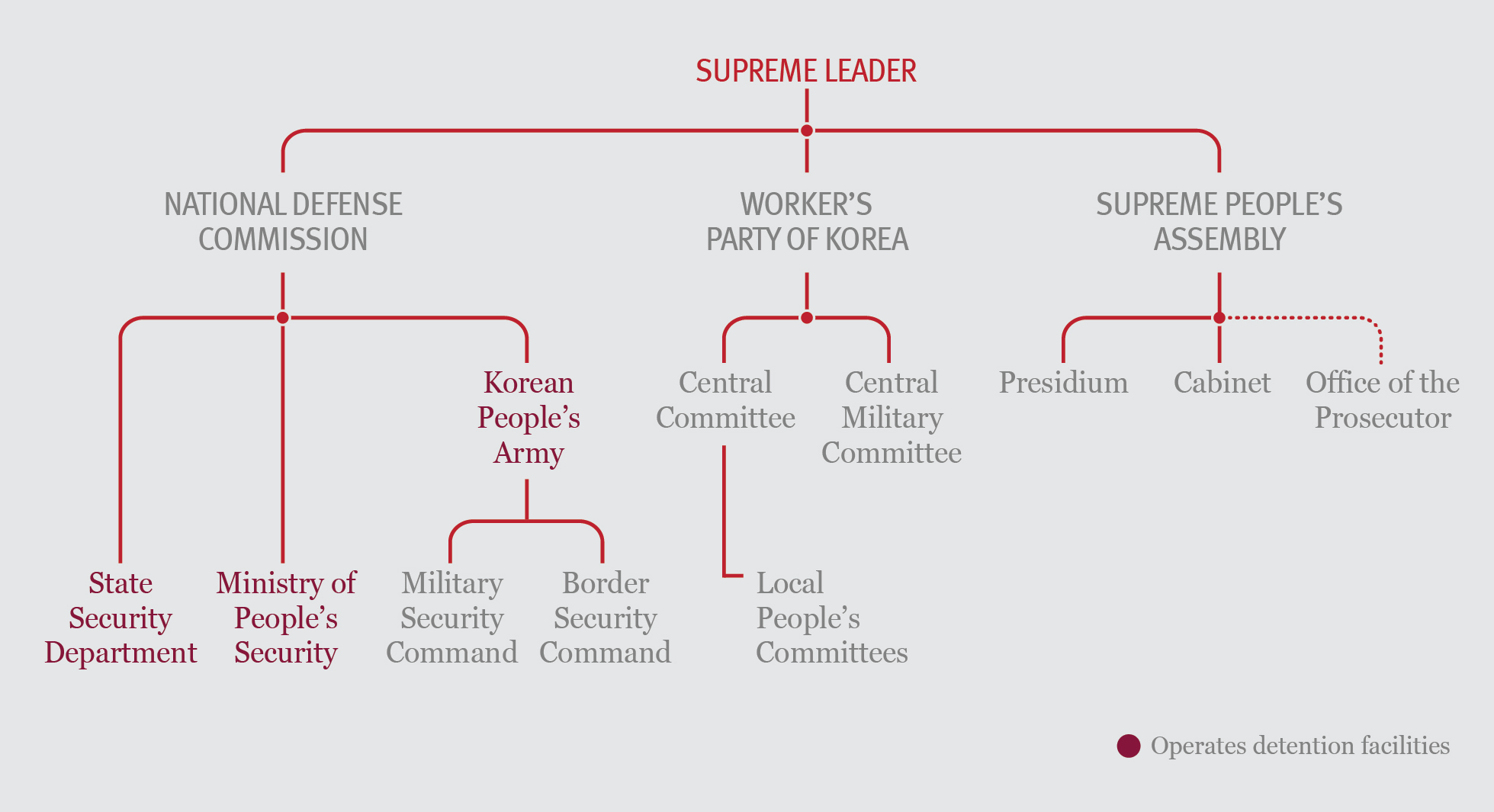

Figure 4. Key Institutions Cited in the UN COI on North Korea

In North Korea, detention facilities and political prison camps—where many of the most severe human rights abuses are committed—are all administered by institutions under the National Defense Commission which reports directly to Kim Jong-un. The UN COI on North Korea lists the State Security Department, the Ministry of People’s Security, and the Korean People’s Army as bearing primary responsibility. Figure 4 shows that Kim Jong-un serves as the First Chairman of the National Defense Commission, the most powerful state organ in North Korea.

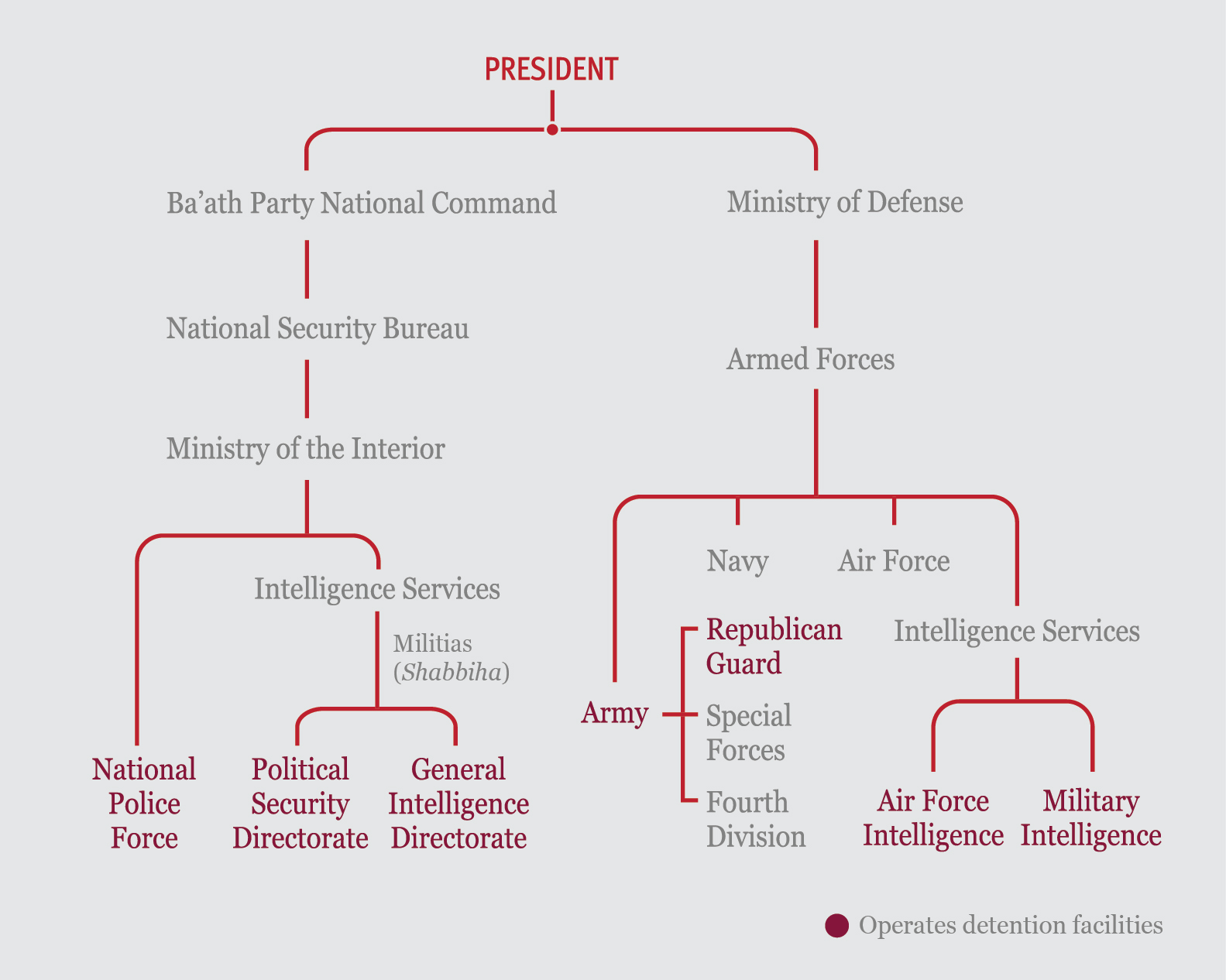

In contrast, Syria is characterized by a diverse assortment of detention and interrogation facilities operated by different intelligence agencies and branches of the Ministry of the Interior and Ministry of Defense as seen in Figure 5. Syria has four separate intelligence agencies: the General Intelligence Directorate, the Political Security Directorate, Air Force Intelligence, and Military Intelligence. Each of these agencies officially carries out different intelligence functions, from covert overseas operations to monitoring domestic security services and the public. But they also enjoy considerable autonomy in terms of detention and interrogation of individuals as well as overlapping jurisdiction within Syria. Importantly, they officially answer to officials in the Ministries of Interior who, in turn, report to the National Security Bureau and the Ba’ath Party National Command.

Figure 5. Key Institutions Cited in the UN COI on Syria

What Figures 4 and 5 illustrate are the considerably different organizational structures through which the North Korean and Syrian regimes repress their citizens. Whereas in North Korea this process is administered under the supervision of the National Defense Commission directly controlled by Supreme Leader, in Syria there are numerous bureaucratic layers that exist between President Assad and the agencies. This is further highlighted by the fact that in the UN COI on Syria, Bashar Al-Assad is never directly accused of responsibility for human rights violations. In contrast, the UN COI on North Korea specifically references Kim Jong-un in his role as “Supreme Leader.”

North Korea Commits Every Crime against Humanity While Syria Does Less

With the exception of the crime of apartheid, the UN COI on North Korea accuses the regime of committing every single act that article 7 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court defines as a crime against humanity. In contrast, the UN COI on Syria accuses the regime of six counts: murder, torture, rape or other forms of sexual violence of comparable gravity, imprisonment or other severe deprivation of liberty, enforced disappearances of persons and other inhumane acts of a similar character. While the absence of the crimes of extermination, enslavement, forcible transfer of population, and persecution in Syria does not reduce the severity of the other crimes, it does suggest that the violence was not initially aimed at the total subjugation of the Syrian people.

This is because Syrian institutions significantly lack the cohesive chain of command to carry out such crimes. To implement a policy of extermination, mass enslavement, and population transfer requires agencies akin to what existed in Nazi Germany or Khmer Rouge Cambodia. As mentioned in the previous section, Syria, however, is characterized by multiple agencies and intelligence services that operate their own detention facilities in a fragmented fashion. Furthermore, because its central security organs were designed to protect the urban regime elite, the security services were never designed to exterminate or enslave the three-quarters of the population who are Sunni.

Figure 6. Crimes against Humanity by North Korea and Syria

Figure 6 illustrates how every crime against humanity is committed against North Korea’s citizens, especially political prisoners. Responsibility for these actions is attributed to the State Security Department, Ministry of People’s Security, and the Korean People’s Army, in particular. In contrast, crimes against humanity in Syria were largely related to the imprisonment, torture, and other mistreatment of citizens. Also, different branches of the government’s security apparatus perpetrated different crimes.

Disparity of International Reaction: The World Focuses More on Syria than North Korea

Over the past decade, the international community has adopted a number of actions against North Korea, such as US Presidential Executive Orders, EU Council Regulations, and UN Security Council Resolutions. But, all of those actions have been targeted at North Korea’s WMD program, not its human rights violations.

One might assume that this is attributed to the short time span because the UN COI report on North Korea was just released in February of this year. Yet, the time limit was not a hurdle for Syria’s human rights violations at all. The first UN COI report on Syria was released in December 2011, while US Presidential Executive Orders against its human rights violations were first issued in April 2011 followed by two more by the end of 2011. Similarly, the EU Council Regulations regarding the Syrian human rights issues were first announced in May 2011 and four more regulations were issued within the year. The UN Security Council has also adopted its first Resolutions in April 2012 and two more in the same year.

While there have been US human rights-related acts against North Korea, such as the US North Korean Human Rights Act of 2004, the absence of Presidential Executive Orders has meant there have not been any sanctions or punishment. The EU Parliament has likewise also adopted resolutions on North Korean human rights since 2010, and the UN Human Rights Council has acted with Resolution A/HRC/19/L.29 on North Korean human rights (March 22, 2012), UN Special Rapporteur report (February 21, 2011), and the Universal Periodic Review Working Group report on North Korea (December 11, 2009). However, these actions are rather a form of declaration significantly lacking actual pressure on the Kim regime. Arguably, despite the more deplorable human rights situation in North Korea, international attention seems to focus more on the human rights situation in Syria.

There are two main factors to explain this paradox. First, North Korea impinges upon vital international security and energy interests less than the Middle East. Syria, thus, is a more important consideration. The region is deeply related to the stakes of the US in terms of oil resources, radical Islam, and the defense of Israel. The EU also has inevitably focused on its immediate region since its domestic politics is often shaped by immigration from the Middle East and its colonial legacy.

The flow-on effects of human rights abuses in Syria on neighboring countries in the form of refugee movements and the proliferation of weapons and armed groups are far more dangerous than North Korea’s largely contained internal repression. The threat that Syria’s human rights violations pose for key US and EU allies such as Israel, Jordan, and Turkey require more urgent involvement than in North Korea. Likewise, instability in Syria threatens Western economic interests in the Gulf as its draws in neighboring countries and regional powers in a proxy conflict. As a matter of fact, the US has invoked the principles of humanitarianism to post-hoc justify its invasion of Iraq in 2003, or criticize the legitimacy of authoritarian regimes in Iran in 2009, Egypt in 2011, and Syria today.

Secondly, it seems also plausible that international focus has been lower in North Korea than Syria due to the limited information regarding the human rights situation inside the country often caused by its self-imposed isolation. In North Korea, contact with the outside world remains almost nonexistent. The few foreign travelers to the country are closely monitored and rarely come into contact with average North Koreans. Similarly, the absence of any civil society groups to expose abuses or pressure the government means that much of information surrounding North Korean human rights comes from defectors living outside the country.

In Syria, on the other hand, until the start of the Syrian uprising in March 2011, foreigners could still travel to Syria and the country still had a budding, if heavily censored, civil society. Tourism existed, travel was possible, and foreign non-governmental organizations also operated in the country. Therefore, the international community was able to criticize the trials of human rights activists and detention centers in Syria.

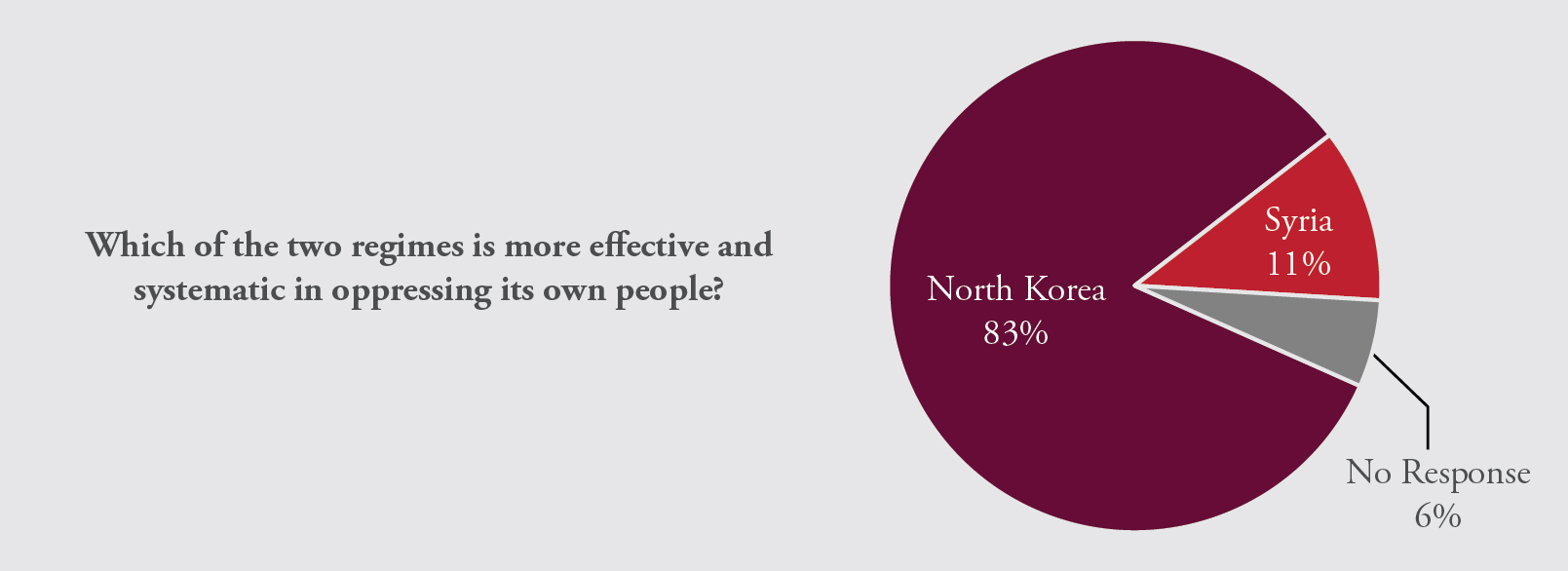

A survey of thirty-four policy experts at think tanks and universities mainly in the US conducted by the Asan Institute for Policy Studies from May to July 2014 confirms that human rights violations in North Korea are graver than those in pre-civil war Syria. According to the survey, 83% of respondents believed that the North Korean regime was more effective and systematic in oppressing its own people than Syria [see Figure 7]. Similarly, 77% of respondents thought that North Korea had a worse human rights record while 17% responded that Syria was worse.

Figure 7. Gravity of Human Rights Violations in North Korea and Syria

Regarding international reaction to human rights violations in the two countries, 66% of experts responded that the international community has focused more on the subject of Syria’s human rights situation whereas 14% disagreed [see Figure 8].

Figure 8. International Response to Human Rights Violations in North Korea and Syria

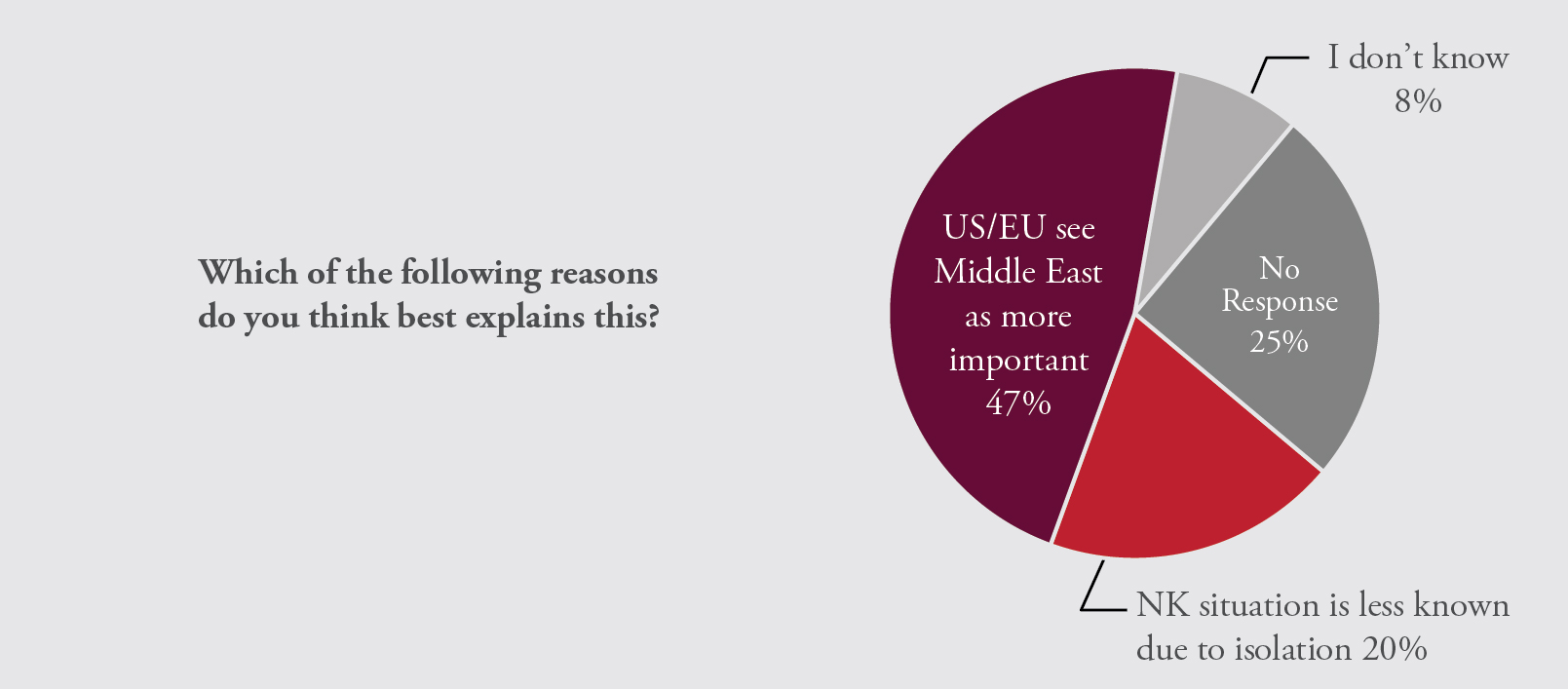

When asked why they viewed Syria has received more attention from the international community, 47% thought it was because the US and EU viewed the Middle East as a more strategically important region, while 20% thought it was due to North Korea’s isolation and the lack of available information regarding its human rights abuses [see Figure 9].

Figure 9. Explanations for the International Responses to Human Rights Violations in North Korea and Syria

Conclusion

The findings of the UN COIs on North Korea and Syria (circa March 2011-February 2012) offer useful insights into two of the world’s worst human rights offenders. The North Korean regime maintains complete control over its population. The regime in Syria, however, faced peaceful demonstrations during the era of the Arab Spring followed by a brutal crackdown and human rights abuses over the course of a year before the country entered a civil war.

The Kim regime of North Korea is a more brutal, effective human rights abuser than the Assad regime of Syria. A comparative analysis of both COIs shows that the former’s crimes against humanity are more systematic under a totalitarian structure directly administered by Kim Jong-un compared to the latter’s fragmented authoritarian responses. The shorter and tighter operational chain of command between institutions is directly supervised by the supreme leader in North Korea compared to the overlapping chains existing between the president and the institutions in Syria. Moreover, the regime of North Korea commits all counts of the Rome Statue’s crimes against humanity, but the Syrian regime is only charged on six counts.

However, there has been an ironic disparity in that the international community pays less attention toward human rights violations in North Korea than Syria in terms of issuing US Presidential Executive Orders, EU Council Regulations, and UNSC Resolutions against the regimes. It is mainly because the former is less closely related to the vested interests of the US and EU in terms of security and energy than the Middle East. It is also because North Korea, as an extremely closed country, strictly controls any contact and information flows inside and outside the country compared to Syria.

The survey results demonstrate that experts are aware that the North Korean regime is a far more systematic violator of human rights than the Syrian regime. Also, experts perceive the existence of the international community’s lower focus on North Korea despite its more grave human rights violations compared to Syria. They believe that deliberate indifference accounts for this disparity more than a lack of information.

The North Korean people have suffered from international indifference for over half a century. Furthermore, the issue of human rights was often overshadowed by the issue of nuclear proliferation. The South Korean government itself has been often hesitant to raise the issue out of fear that it would jeopardize inter-Korean negotiations. Japan has also focused on the issue of the return of kidnapped Japanese nationals and North Korea’s nuclear threat. China, naturally, had no desire to concern itself with the internal politics of a nominal ally. Like its South Korean and Japanese allies, the driving motivation behind U.S. policy towards North Korea has been its nuclear and ballistic missile threat.

Nonetheless, these excuses are no longer so easily justifiable since the release of the COI report on North Korea. If the lack of vested interests in North Korea compared to Syria is not alterable, then greater efforts should be made to raise public awareness of North Korea’s human rights situation. The recent decision to establish the UN’s Seoul office to further investigate and monitor the human rights situation in the country will be a corner stone in publicizing “the unknown horror.” This field office should serve as a pivotal center to facilitate the activities of many NGOs advocating human rights in the North. Besides, it is time that South Korean lawmakers finally pass the long-delayed North Korean Human Rights Act, as well.

Moreover, more targeted sanctions against senior government officials and agencies responsible for crimes against humanity in North Korea should be implemented. All of their assets and property should be blocked as we can see from the sanctions against the Syrian human rights abusers. Indeed, sanctions should be issued against human rights violations in North Korea, in addition to its WMD program. In doing so, the international community and the South Korean government could put more pressure on the North Korean regime.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter