Evaluating President Park Geun-Hye’s Foreign Policy in its 1st Year1

President Park Geun-Hye Administration’s 1st Year

February 25, 2014 marks President Park Geun-Hye’s first year as President of South Korea. Despite facing a host of domestic and foreign challenges throughout the year, President Park’s approval rating remained remarkably buoyant through her first year in office. While approval rates reached their highest point in July 2013 at nearly 70%, even at their lowest point in December 2013, they still hovered around 50%. Her time so far in the Blue House draws stark contrast with the experiences of previous administrations, whose high approval ratings—hitting 80% in certain cases—plummeted during the course of their first years.

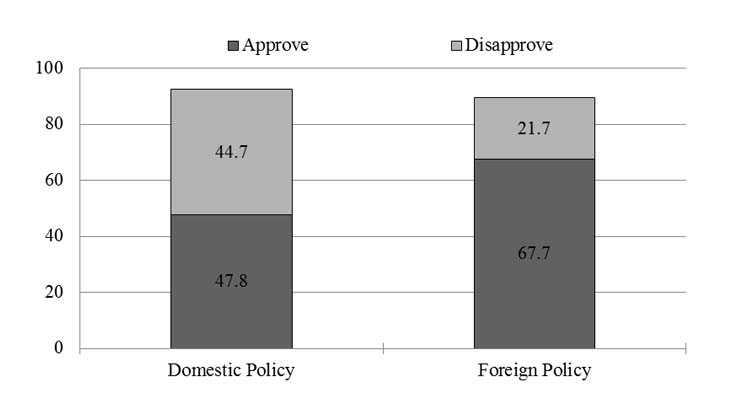

The numbers suggest that President Park’s first year was a success. However, it is important to go beyond the numbers to evaluate the effectiveness of her policies. According to surveys conducted by the Asan Institute for Policy Studies, the public was strongly in support of President Park’s performance on foreign policy, with 67.7% stating as such. In contrast, 47.8% approved of her handling of domestic policy issues. Support for President Park’s handling of foreign policy was relatively high (30.9%) even among those who do not approve of her job performance overall. In fact, the survey results indicate that her performance on foreign policy was well received by the public regardless of party affiliation, ideology, or age. Even 52.9% of those who consider themselves to be progressive were in favor of her policy.

Figure 1: Evaluation of President Park’s 1st Year as President

This issue brief offers an examination of President Park’s foreign policy during her first year in office. Specifically, it differentiates between results of public opinion polls and expert policy analyses while highlighting the dangers associated with taking public opinion polls at face value. Its primary goal is to get to the core of President Park’s foreign policy evaluation to allow for smoother implementation of her foreign policy for the remainder of her presidency.

Former-President Lee Myung-bak’s Foreign Policy Remains Large in the Public Minds

Upon taking office, the Park administration outlined her foreign policy in three forms: 1) ‘Trust-building process on the Korean Peninsula’ (hereafter, trust-building process); 2) the ‘Northeast Asia Peace and Cooperation Initiative (NAPCI),’ and; 3) ‘middle power diplomacy.’ A year later, the specifics of these policies—their goals, ways to achieve these goals, and their achievements so far—are yet to be detailed.

The trust-building process is, first and foremost, a defensive policy in response to inter-Korean tensions created by North Korea’s provocations. Based on this defensive posture, it aims to encourage inter-Korean cooperation as a way to build trust which could then lead to sustainable peace. Specifically, this is not a policy that simply allows South Korea to send unconditional aid to the North. Rather, it is a step-by-step approach to build trust with the North based on tangible results.

The NAPCI reflects President Park’s effort to resolve what is known as the Asian Paradox—the situation in which growing economic interdependence has failed to generate political and military trust among Northeast Asian nations. This policy aims to develop bilateral or multilateral cooperation mechanisms among Northeast Asian countries and, in the end, create an environment conducive to peace and prosperity.

The third aspect of President Park’s foreign policy is middle power diplomacy, which aims to build upon South Korea’s middle power status to engage in important international issues. More specifically, it aims to strengthen Korea’s network with other middle powers to become a global leader that contributes to global peace and improvement of human rights, improves cooperation with the rest of the world on global security and economic issues, and increases its development cooperation efforts.

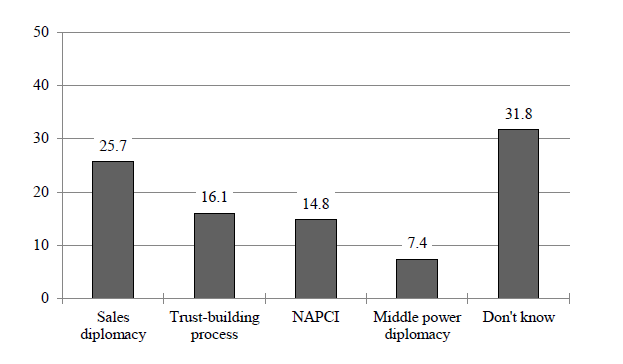

However, public opinion survey results show that President Park’s three signature foreign policies have thus far failed to grab the attention of the public. When respondents were asked which foreign policy element first came to mind when thinking of President Park’s first year in office, 25.7% answered ‘sales diplomacy’—a policy most associated with former-President Lee Myung-Bak (Figure 2). Only 16.1% and 14.8% of respondents, respectively, identified the trust-building process and the NAPCI. Interestingly, 31.8% of the respondents answered “Don’t know.”

Figure 2: President Park’s Signature Foreign Policies

Further analysis of the numbers reveals that among the 67.7% that supported President Park’s handling of foreign policy, 29.1% identified sales diplomacy as President Park’s key foreign policy and 25.4% answered that they did not know. Among supporters of President Park’s Saenuri Party, 31.6% chose sales diplomacy and 21.9% answered that they did not know. Similarly, 85.0% of those aged 60 and older agreed with President Park’s foreign policy, yet 41.0% stated that they did not know—a phenomenon that we call the “I Support, Don’t Know” phenomenon.

The fact that sales diplomacy was incorrectly identified by many as President Park’s main foreign policy means that her approval ratings must be taken with a grain of salt. These numbers should not dominate how her performance is evaluated. Instead, her administration’s strategic decisions—and how those decisions led to increased positive evaluations of the administration—must be included in the analysis.

The identification of sales diplomacy as President Park’s signature foreign policy was likely influenced by her frequent international trips. In 2013, President Park attended the APEC, ASEAN, and EAS summits, and also had 10 summit meetings abroad with the leaders of other countries—all of which were portrayed by the media as part of her sales diplomacy.

It is important to note that President Park’s three signature policies were, from the public’s point of view, indistinguishable from that of President Lee. Mr. Lee was also very active in international summits—setting a record among Korean presidents for the number of summits held while in office—and championed sales diplomacy. However, sales diplomacy is a policy that produces no tangible economic results, leading to doubts about its viability as a country’s signature foreign policy. More importantly, the fact that the public could not distinguish her policies from President Lee’s opens the possibility that she has failed to explain her policy to the public. Given these results, we can conclude that her foreign policy so far has not been as successful as it is perceived by the public.

Of course, the diplomatic circumstances President Park inherited were not ideal. An argument can be made that her signature policies were unable to take shape as a result of North Korea’s continuing provocations and the political provocations of Abe Shinzō’s administration coming via statements regarding historical issues. Regardless, the fact that one in every three Koreans was unaware of President Park’s foreign policy initiatives must come as a disappointment for the Blue House, especially when foreign policy is considered a strength. Therefore, blaming the diplomatic circumstances as reasons for President Park’s foreign policy’s falling short of expectations appears insufficient.

Trust-building on the Korean Peninsula and Northeast Asia Peace and Cooperation Initiative

While President Park’s trust-building process had its challenges, it did manage incremental successes in the form of re-opening of the Kaesong Industrial Complex, family reunions, and the Najin-Hasan Railway. President Park’s high approval rating appears to have been influenced by these small successes and her principled approach to North Korea. At the same time, the fact that North Korea’s nuclear weapons program remains unresolved can be interpreted as a reason why sales diplomacy was more publicly recognized.

In order for the trust-building process to take meaningful steps, North Korean security issues must be resolved. How President Park approaches this will be a difficult test. While North Korea has recently adopted an open policy towards the South, it is not yet clear whether this was the result of President Park’s trust-building process or simply the result of North Korea’s short-term strategic decisions based on the changing regional atmosphere.

Another challenge for the Park administration is to manage its relations with nations that have vested interests in the North Korean issue. The United States has shown its support for President Park’s trust-building process and, specifically, her ability to break away from the traditional inter-Korean relationship, which can be described as a cycle of ‘provocations, negotiations, and compensations’. On the other hand, China has expressed its expectation that the Park administration will approach North Korea in a more flexible manner. For President Park, who has advocated for the importance of South Korea-U.S.-China cooperation, how she approaches these relations will be critical.

With regard to the NAPCI, the administration has only conceptually outlined objectives or a roadmap on how to achieve those objectives. This ambiguity has led to numerous interpretations by experts. Thus, any assessment on such foreign policy by the general public is most likely based on superficial, erroneous, and possibly conflicting information.

When the public was asked about the effectiveness of the NAPCI in solving the issues in the region, a near majority (47.9%) answered positively. However, from the perspective of policy implementation, it remains difficult to assess the initiative with such optimism. Thus far, the only visible diplomatic efforts have been explaining the initiative to the United States, requesting support for it, and getting the United States and China to support it as a basic principle. Therefore, it is safe to say there has been no specific policy development so far.

The most serious problem of slow progress on the NAPCI is the significant gap between the current strategic environment and the objective of the NAPCI. While the NAPCI calls for cooperation aimed at fostering trust between the nations in Northeast Asia, circumstances in the region since President Park took office have made such cooperation less likely, not more. While the international political environment in Northeast Asia is currently conducive to a negative peace—one of tensions but of no open conflict—the NAPCI insists upon a positive peace—a genuine cooperation and trust between the countries. Consequently, the implementation of the initiative is difficult and is not creating active support from the surrounding nations.

Second, the NAPCI employs a soft approach to improving inter-state tensions and volatile strategy-security environment. Instead of directly addressing traditional issues, such as security, which could bring conflict, it proposes initial cooperation in relatively less sensitive issues such as non-traditional security to build trust among nations and finally to establish peace and cooperation in Northeast Asia. However, as previously noted, the region is currently an environment where countries are colliding and even assuring the least amount of negative peace is difficult. In this context, the approach can hardly create cooperation among the countries in the region.

Also, the constructivist approach—a socialization process of changing perceptions through conversation and trust building—is best-suited for the long-term but not for the current situation in Northeast Asia. When inter-state conflict is at its peak, such an initiative is not an effective policy means to solving conflicts among the Northeast Asian countries.

Evaluation of Foreign Policy towards Neighboring Countries

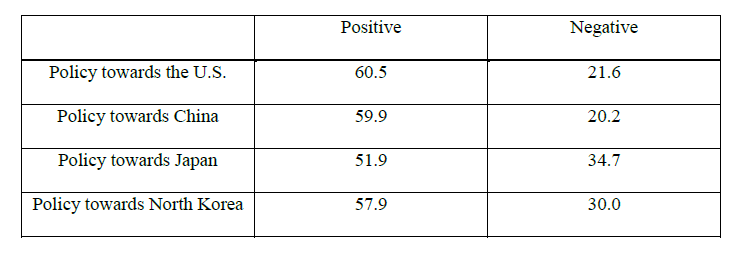

Public evaluation regarding President Park’s foreign policy towards neighboring countries also showed largely positive results. With regard to policy towards the United States and China, 60.5% and 57.9% of respondents, respectively, positively evaluated policy towards these countries (Table 1). This may have been the result of successful summit talks with both countries. Approval ratings for President Park support this, with July marking the high point—not long after the successful respective summits with President Obama and Premier Xi Jinping.

Table 1: Evaluation of Foreign Policy towards Neighboring Countries

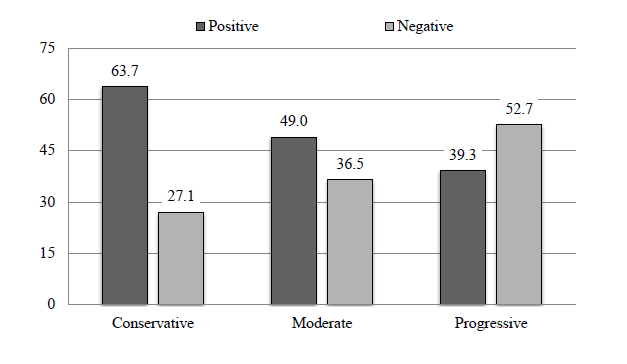

President Park’s policy towards North Korea was also positively evaluated. The shutdown of the Kaesong Industrial Complex demonstrated a firm stance against the North, thereby leading to positive evaluations among the general public. Relations with Japan, on the other hand, were the least positively evaluated with 51.9% positive and 34.7% negative. In particular, the evaluation diverges distinctively according to one’s ideological stance. While evaluations regarding policy towards other neighboring countries were positive regardless of ideological stances, there was a significant gap between conservatives and progressives in evaluating policy towards Japan. Whereas 63.7% of conservatives supported the Park administration’s hardline policy towards Japan, 52.7% of progressive evaluated this policy negatively (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Evaluation of Policy towards Japan: By Ideological Stance

Following the evaluation of policy towards the United States, President Park’s policy towards China came as the second highest. When asked which aspect of policy towards China was most successful, the responses appeared in order of trust building (29.9%), economic cooperation (23.9%), military security (18.4%) and cultural exchanges (13.5%). Interestingly, when respondents who evaluated the policy negatively were asked which aspect was most unsuccessful, the results appeared in the same order; trust building (34.8%), economic cooperation (19.2%) military security (18.2%) and cultural exchanges (10.9%). These results illustrate the complex views Koreans have of China.

The fact that ‘trust-building process between governments’ ranked first in both positive and negative evaluations depicts how highly the public regards such efforts. On the other hand, it also highlights concerns about how efforts to develop a strategic balance between the United States and China may erode trust from both. As mentioned previously, South Korea was successful in garnering support from the United States and China for the Trust-building Process on the Korean Peninsula and the NAPCI. However, the United States and China may view Korea differently given their strategically competitive relations.

The United States seems to think that the Park administration has moved closer to China following the Lee administration’s distancing from China. In particular, conservative Americans perceive that Japan, not South Korea, is the country that will mobilize its forces for the United States should there be conflict in the region. China believes that South Korea will ultimately stand by the United States even though Korea places emphasis on maintaining an amicable relationship with China for the purposes of economic benefit. Thus, it will become much more difficult for Korea to find a strategic balance between the United States and China. A worst case scenario would mean that Korea must choose between the two superpowers.

The leaders of Korea and China have come to an agreement on certain crucial issues as evidenced by the joint statement issued in June 2013: establishing a direct communication channel between the chief of the Blue House National Security Council in South Korea and China’s State Councilor for foreign affairs in terms of diplomacy and security; organizing a mutual visit of foreign ministers on a regular basis as well as setting up a hot line; holding a strategic dialogue between vice foreign ministers twice a year and promoting the foreign and security dialogue; policy dialogue between parties; and a joint strategic dialogue between the national research centers of the two nations. However, despite the talks between the chief of the Blue House National Security Council and China’s State Councilor for foreign affairs just before the surprise expansion of China’s Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ), the Park administration could neither prevent nor mediate the situation. Also, a hot line between the foreign ministers at the time had little effect. The same limitation arose with regard to North Korean nuclear issues, which are the key items on the security agendas between Korea and China.

Reunification as a “Jackpot”

In President Park’s first press conference, held in early January 2014, President Park stated that Korean reunification would be a “jackpot” for Korea. This statement brought national attention to reunification, making it a major conversation topic in political circles.

Despite the number of headlines the statement generated, the public is largely ambivalent. While 47.6% agreed with the president’s statement, 37.4% disagreed. In particular, it was those who identify as progressive and are younger than 40 years who were the most negative on the statement. For those in their 20s, 38.9% agreed and 28.6% of those in their 30s said the same. Among those in their 50s and 60s and older, those numbers were 62.8% and 62.2% respectively.

Much of the disagreement among those in their 20s and 30s likely stems from the perceived negative financial consequences of reunification. In a survey conducted in 2013, it was respondents in their 20s who were the most pessimistic about the personal financial ramifications of reunification, with 74.6% stating as such.

The divide among political ideologies is also worth noting. While 65.5% of self-identified conservatives agreed with President Park’s jackpot theory, 37.8% of progressives stated the same. Considering that the discourse for unification had been prevalent among liberals, the fact that conservatives show more support for the jackpot theory suggests that unification discourse has become an ideological issue. That is, conservatives support whatever a conservative president says, but liberals oppose it even though they have owned and supported the issue for a long time. This further suggests any future administration will find it extremely difficult to elicit a pan-national discourse on unification.

Conclusion

As is often the case for many diplomatic plans of a new administration, specific visions and contents of foreign policy are likely to be known only superficially. As a result, the assessment of the general public about this superficially-known foreign policy plan is made without knowing the concrete direction and without closely examining the results. Similar results were found in the opinion polls of the Asan Institute. Although a majority of people view President Park’s foreign policy as ‘successful,’ most respondents did not accurately identify her policies.

Unlike the favorable evaluation of the general public, it is hard to view 2013 as being productive in diplomatic outcomes. The Trust-building Process on the Korean Peninsula and the NAPCI appear to be well-intentioned but underachieved. However, the diplomatic environment in 2014 is expected to improve from 2013. The reunions Korean families separated by the Korean War were agreed to by the two Koreas, and the United States is pushing for a resumption of the Six-Party Talks.

Furthermore, with President Obama’s Asian tour in April 2014, the Korea-Japan relationship appears to be open for diplomatic talks as his message will focus on ways to improving ties between the two. With a much more favorable environment, we anticipate President Park’s three major foreign policy initiatives, the Korean Peninsula Trust-building Process, the Northeast Asia Peace and Cooperation Initiative, and middle power diplomacy, to be fully developed this year.

Appendix

The sample size of survey was 1,000 respondents over the age of 19. The survey was conducted by Research & Research (Feb. 4-6, 2014), and the margin of error is ±3.1% at the 95% confidence level. The survey employed the Random Digit Dialing method for mobile and landline telephones.

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 1

Special thanks to John J. Lee and Karl Friedhoff for English translation.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter