Kim Jong Un’s approach to inter-Korean relations is defined by three pillars: (1) achieving dominance over South Korea, primarily through nuclear weapons; (2) promoting “peace” only as a rejection of regime/system change; and (3) strategically cutting off inter-Korean ties to resolve internal dilemmas. Given this posture, any early push for engagement or cooperation risks creating a structure that North Korea could exploit.

North Korea’s “Two Belligerent States” Framework and Its Implications

Kim Jong Un’s Efforts to Establish a North Korea-Dominant Inter-Korean Relationship

North Korea sees a “relationship between two belligerent states” as a tool for securing strategic superiority. Since offsetting South Korea’s conventional military advantage will take time, Pyongyang deems nuclear weapons essential. Domestically, it tries to cultivate sympathetic sentiment in South Korea, while externally attempting to isolate U.S. involvement and gain support from China and Russia. These efforts, if successful, could enable North Korea to assert dominance despite economic inferiority. Some argue that flexible policies might transform hostility into peaceful coexistence, but given that this hostility stems from Kim’s obsession with superiority, genuine reconciliation is unlikely unless South Korea accepts subordination.

North Korea’s Definitions of “Peace” and “Unification”: A Rejection of Change

For Pyongyang, peace is only possible if its regime and system remain untouched—rendering South Korea’s engagement efforts incompatible. Similarly, “unification” no longer reflects peaceful ethnic solidarity but remains a militarized objective based on hostility. Therefore, the two-state hostility framework is more likely to sustain tensions or facilitate forced unification than enable peaceful coexistence.

Anxiety Behind Confidence: North Korea’s Strategic Calculus

Despite its assertive rhetoric, North Korea’s behavior suggests insecurity. A confident regime would project legitimacy through symbolic engagement. Instead, North Korea’s focus on hostility and isolation reflects a belief that increased contact would undermine regime stability domestically, within South Korea, and internationally. This behavior reveals Kim Jong Un’s deep anxieties rather than his strength.

North Korea’s 2025 Strategy: Deepening Isolation and “Global Engagement, Southern Containment” (通外封南)

North Korea’s 2025 strategy may evolve from “engage the United States, isolate the South” to “engage external powers, isolate the South.” By strengthening ties with Russia and authoritarian regimes, it aims to expand diplomatic influence, provoke more active Chinese involvement, and pressure the United States for concessions. It may also attempt to weaken the ROK-U.S.-Japan trilateral cooperation. North Korea will likely use Russia as leverage in dealings with the United States and China, trying to ensure it is not marginalized in great power politics. Despite mistrust, Pyongyang still values direct negotiation with the United States as a pathway to economic development and global market access—though it will avoid appearing to initiate talks.

South Korea’s Strategic Response in 2025

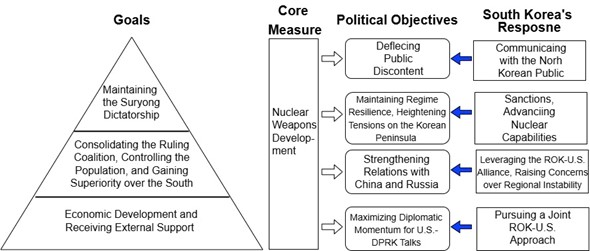

Figure 1. North Korea’s Goal Hierarchy and South Korea’s Response

(1) Maintain the Goal of Complete Denuclearization: Denuclearization remains essential to preserving South Korea’s security, strategic advantage, and unification prospects. Even if future U.S.–DPRK talks under Trump prioritize homeland security, Seoul must ensure that “complete denuclearization” remains a shared objective with Washington.

(2) Pursue Peace and Engagement Based on Deterrence: Strengthen sanctions via the new Multilateral Sanctions Monitoring Team (MSMT), coordinate carefully during U.S.–DPRK talks, and consider secondary sanctions. If nuclear freeze is pursued, demand reinforced extended deterrence—possibly redeploying tactical nuclear weapons. Peace and cooperation must be tied to economic incentives that both regime elites and North Korean citizens find valuable.

(3) Continue Pursuing Unification through North Korean Change: Gradual change remains essential—emphasizing human rights and access to information. Unification should be framed as improving quality of life, not regime collapse. A flexible process starting with a North–South confederation (the “Korean Commonwealth” stage according to the National Community Unification Formula) based on denuclearization and reform can build toward a unified state later, with input from future generations.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter