2019 in Review

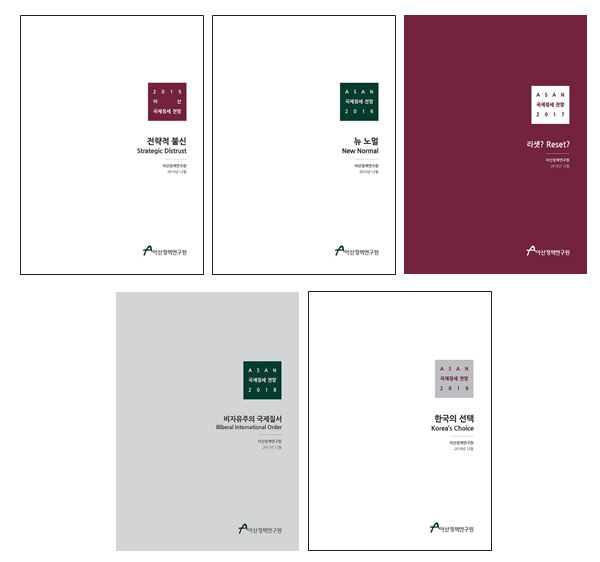

The dramatic restructuring of international relations over the past decade has taken many forms. The Asan International Outlook series has sought to capture these key inter-related changes under annual themes such as “Strategic Distrust” (2015), “New Normal” (2016), “Reset?” (2017) and “Illiberal International Order” (2018). This era of the “new normal” is defined by deepening inter-state strategic distrust and is accelerating a “reset” in the international order beyond just modest changes. An illiberal international order also emerged during this period. In other words, the various themes presented since 2015 have reflected distinct yearly trends rather than a complete, exclusive account of this period. Indeed, more time may be needed before the pieces of the puzzle can be put together and the full picture becomes clearer.

Figure 1. Recent Editions of the Asan International Outlook (2015-2019)

Source: Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

The year 2019 revealed yet another puzzle with the dawn of what can be called the era of “hybrid geopolitics.” The role of traditional geopolitics, which dominated the nineteenth century, declined in the twentieth century with scientific and technological progress and the advent of international regimes. But the twenty-first century, and 2019 in particular, saw its resurgence as science and technology have created new borders. While it is difficult to explain this trend in the context of bilateral relationships or regional development, when looking at the entire international system, hybrid geopolitics is a phrase that aptly describes the world in 2019.

This new form of geopolitics takes on distinct characteristics and forms in different regions. In Europe, Brexit is redefining the European Union’s central place in the regional landscape since the late twentieth century as countries look to advance their own interests. With changes in U.S. alliance policy under the Trump administration, we cannot rule out potential policy differences on the transatlantic alliance between the U.S. and the U.K. with Continental Europe. In the Middle East, Russia re-emerged as a major actor due to its geographic proximity after years of diminished influence following the Cold War and in sharp contrast to the declining U.S. role in the region.

In Northeast Asia, the complexity of hybrid geopolitics has been on most dramatic display as evidenced by strategic competition between the United States and China. The U.S.-China contest is playing out both in traditional geopolitics but also in the “new frontiers” of cyber space and science and technology. In 2019, Northeast Asia was the epicenter of this competition. Japan tried to improve relations with China and Russia from within the framework of the U.S.-Japan alliance to limited avail. China and Russia, in turn, strengthened strategic ties with each other in the midst of the U.S.-China competition, but continued to show different political calculations. Meanwhile, North Korea tried to expand its room for maneuver in the region’s new geopolitical order but was unsuccessful in gaining tangible results as the Hanoi Summit talks broke down.

The problem is that, compared to the past, the world of hybrid geopolitics is much more unclear and also increases the likelihood of an unstable regional and/or international order. There is growing strategic distrust and rivalry among the major countries, despite the increasing need for cooperation on emerging new security issues. Each country’s strategic calculation to ensure its survival and prosperity has also become increasingly complex. It is in this context that we can understand the choice of the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) to avoid being forced to side with either China’s Belt and Road Initiative and the U.S. Indo-Pacific Strategy by trying to develop a common strategy of its own. On the other hand, Korea’s choices are more complicated given it cannot rely on the collective solidarity that its ASEAN partners enjoy and remains a divided country surrounded by more powerful neighbors. Thus, 2019 was a year that put these concerns on stark display.

Northeast Asia: Leading the New Order and the Rise of Hybrid Geopolitics

Two phrases that underscored the Northeast Asian order in 2019 were “a prelude to a leadership contest over a new order” and “the emergence of hybrid geopolitics and geo-strategy.” The new order had the following unique aspects. First, beyond territorial borders, competition greatly increased over the acquisition and protection of key science and technology innovations along new borders. At the same time, the nineteenth century practise of balancing with geographically proximate states to contain rivals in other regions was revived. The concept of borders is also expanding with the appearance of “virtual borders” due to information distribution and sharing and public opinion formation through the Internet.

Inter-Korean Relations and Denuclearization on Ice

Despite high hopes, 2019 ended with inter-Korean relations at a standstill. The icy atmosphere caused by the breakdown of U.S.-North Korea working-level denuclearization talks seemed to hang over the entire Korean Peninsula. North Korean criticism of the South grew louder and inter-Korean dialogue channels were frozen. Chairman Kim Jong Un’s much anticipated visit to Seoul did not occur and people-to-people exchanges broke down. On the military side, North Korean launches of short-range missiles, firing of long-range artillery and coastal artillery threatened to jeopardize the 2018 inter-Korean Comprehensive Military Agreement.

The hopes raised in 2018 for North Korea’s denuclearization were all but gone in 2019. Talks have stalled since the failure of the second U.S.-North Korea summit in Hanoi, while North Korea has fired missiles 13 times in 2019 alone. Through discussions on denuclearization in 2018-2019, North Korea confirmed that its policy position on nuclear weapons over the past 30 years remains unchanged. North Korea has stated that denuclearization is off the negotiation table, demanding the withdrawal of all hostile policies toward it before negotiations can resume. The international community is also re-evaluating its assessment of North Korea’s nuclear capabilities. Given North Korea already possesses dozens of nuclear weapons and is able to secure stable nuclear material, it seems virtually impossible that North Korea will abandon its nuclear weapons program.

America’s Two Faces in 2019

In 2019, the Trump administration achieved mixed results on the economic and political fronts. Economically, President Trump’s push for pro-business policies through tax reform and cutting back environmental regulations pushed unemployment below 4 percent and revitalized the economy. But politically, the Democrats won majority control of the House of Representatives at the 2018 midterm elections. President Trump spent much of 2019 battling the Special Counsel investigation led by Robert Mueller into Russian meddling in the 2016 U.S. presidential election as well as his subsequent impeachment over dealings with Ukraine.

Figure 2. Trump Impeachment Public Hearing

Source: Yonhap News.

On foreign policy, President Trump had said he would seek to dismantle the liberal international order following his inauguration and announced he would withdraw from trade agreements such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the North American Free Trade Agreement, as well as multilateral regimes such as the Paris Agreement on climate change and UNESCO. In its place, a new order centered on bilateralism seemed to be at hand. However, hopes for multilateralism were revived after the signing of the new U.S.-Mexico-Canadian Agreement (USMCA) and the announcement of the administration’s Indo-Pacific Strategy. President Trump is also re-defining America’s alliances with South Korea, Japan, and Europe, and the leadership the U.S. provides, on the basis of what he considers a fair price. On the Korean Peninsula, President Trump has not seen major progress since the breakdown of the Hanoi talks.

China’s Internal Leadership Consolidation amid External Crises

The year 2019 marked the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China and the 40th anniversary of the establishment of U.S.-China diplomatic relations. However, the Chinese leadership faced various foreign and domestic challenges including the U.S.-China trade war and Hong Kong protests. The celebratory mood of the 70th anniversary was short-lived, and the impact of the crisis and challenges were deeply felt by Xi Jinping. In particular, 2019 showed that the U.S.-China conflict was not simply a strategic competition but rather that the two countries are entering a long-term competition for hegemony.

Despite domestic and external challenges in 2019, Xi Jinping’s rule and leadership remains firm. His strong grip on power is closely related to various challenges faced by China including the U.S.-China conflict. In July 2019, China released a Defense White Paper titled “China’s Defense in the New Era.” On the 70th anniversary of its founding, the Chinese leadership wanted to show off the powerful People’s Liberation Army’s war-fighting and war-winning potential as the physical foundation for realizing “China’s dream.”

Figure 3. Hong Kong police officers trying to disperse protesters by firing teargas

Source: Yonhap News.

Japan’s “Beautiful Harmony” Ended in Tensions with Neighbors

Even as Japanese diplomacy ostensibly ushered in the start of a new era of Reiwa meaning “beautiful harmony” in 2019, tensions between Japan and neighboring countries intensified. Japan seized the initiative and took a leading role in bolstering the free and fair, rules-based international order. By hosting large international events such as the G20 Summit and Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD), Japan tried to highlights its leadership to the world. Despite such efforts, Japan’s relations with its neighbors experienced difficulties. The U.S. pressured Japan on defense and trade agreements. Meanwhile, its relationship with South Korea deteriorated in the face of unprecedented and complex conflicts over historical, economic, and security issues. Japan remained a bystander on North Korean denuclearization and its relations with the North went nowhere. Negotiations with Russia over its Northern Territories reached a deadlock and even though Japan tried to resume a relationship with China, there was little progress.

Europe’s Chaotic Spiral

Europe in 2019 could be summed up in one word: chaotic. At the core of the chaos remained Brexit. Over three years since the people of Great Britain voted to leave the European Union in June 2016, there was still no end in sight. The turbulence of British politics over Brexit was linked to the problem of populism, especially right-wing populism, which has swept Europe over the years. European politics also fell into disarray as right-wing populist parties increased their share of seats in the May 2019 European Parliament elections. Not only did the party system need to be rapidly reorganized, but the instability of member state governments in which far-right parties participated increased because of conflicts among the coalition parties. Even as 2019 was a tumultuous period within Europe, it also had conflicts with the United States over the levels of defense spending within the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and American unilateralism in foreign policy.

Russia’s Revived Ambitions in America’s Absence

Having overcome the corruption and economic plundering that followed Russia’s transition from communism, President Vladimir Putin has ambitiously set about restoring Russia to great power status. At the same time, he also looked for a way to resolve disputes with the United States in 2019. In particular, with the end of the long-running Syrian conflict, the dangers of a direct military clash between the United States and Russia dissipated. It also became clear that Russia did not want an all-out conflict with the United States or the European Union as evidenced by the prisoner exchange it agreed to with Ukraine in September 2019.

As Russia re-establishes its imperial status in 2019, a crucial enabling condition is the reckless retreat of the United States from key regions. This was most dramatically seen in the recent crisis with the Kurds. Russia’s active mediating role stood out as Turkish forces proceeded to launch a military offensive against Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) units only three days after the Trump administration announced the withdrawal of U.S. troops from north-eastern Syria. The scene of a United States wanting to wind back its global presence and a Russia aiming to restore its imperial status in Eastern Europe and the Middle East also appears to be repeating itself in Northeast Asia.

ASEAN’s Internal Unity amid External Pressure

Southeast Asia in 2019 was a year of tranquil movement. If 2018 was a year of political changes and controversy, 2019 was a year of political stability and continuity. The highly anticipated elections in Thailand and Indonesia went largely as expected and delivered political continuity in both countries. For ASEAN countries, tensions stemmed instead from the return of geopolitics with the growing U.S.-China strategic competition and their trade war. Southeast Asia is where the U.S. Indo-Pacific Strategy and China’s Belt and Road Initiative overlap, intersect, and collide. Facing pressure from both powers, ASEAN adopted the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific (AOIP). Though it is insufficient to remove the pressure entirely, it might be enough to stave it off temporarily. In this sense, ASEAN took an action on its own way in response to the increased pressure and fast growing challenges from outside the region.

New Emerging Security Challenges on the Rise

Recently, the international community has recognized the importance of emerging security challenges which are mainly environmental and technological problems. Their likelihood and impact are expected to be huge in the future. Environmental security issues like extreme weather, climate change and natural disasters have wrought the most damaging consequences in 2019. Typhoons, hurricanes, and tropical cyclones have become increasingly common and their social and economic damage is increasing. Also, the world has failed to act on resolving technological threats like cyberattacks, information and data theft as well as social crises like infectious disease and irregular migration. In particular, the African Swine Fever (ASF) virus which had spread across China and Southeast Asia reached South Korea where it has required constant responses.

Intensifying Trade Wars

The U.S.-China trade war continued throughout all of 2019. Both sides continued to levy new tariffs on each other’s products and demanded new concessions in multiple rounds of talks. Then, the two sides announced a “phase one” trade deal on October 11, though the details of the deal remained unclear. While the trade war appears to be winding down, the United States continues to resist an early signing of the deal in a bid to maintain its leverage in negotiations.

The dispute between South Korea and Japan was fuelled by the ruling of the Supreme Court of South Korea in 2018 that forced labor victims were able to claim compensation from Japanese companies. On 1 July, Japan announced that it would tighten the export of three chemicals that are critical for the South Korean semiconductor industry and the Japanese cabinet also approved the removal of South Korea from its export “white list.” However, South Korea decided to conditionally suspend the expiration of the General Security of Military Intelligence Agreement (GSOMIA) with Japan. Therefore, both South Korea and Japan could put an end to their trade dispute if Japan allowed exports of three chemicals and restored Korea to the white list.

The Outlook for 2020

The forces that have driven competition and cooperation among states based on “hybrid geopolitics” in 2019 will become more powerful in 2020. At the same time, with this new geopolitical calculation, changes in power relations will also be accelerated both at the regional and global level. Above all, areas of hybrid geopolitics are likely to be more diversified with the continued strategic competition between the United States and China. More specifically, the U.S.-China trade dispute will escalate into a competition for supremacy in the areas of science and technology as well as finance. In addition to geography, they will compete to win others to their side by using their cultural and regime similarities, leadership over international opinion, and security commitments as weapons. Despite this, they are not likely to have an all-out conflict in 2020. Both sides are well aware that their competition is long-term in nature and have sufficient reasons to avoid full escalation.

Nonetheless, it is inevitable that the strategic rivalry between the United States and China will continue and intensify. This is because both sides consider the current competition non-negotiable and are confident that they will eventually win. Whilst emphasizing its allies pay their “fair share” the Trump administration is unlikely to relinquish its influence over its existing allies and partners. In this context, the Trump administration is expected to eventually implement a policy that would implicitly press its allies and partners to accept a multi-faceted “entrapment.”

Rather than backing down from its competition with the United States, China will also try to attract other countries to its orbit both regionally and globally. Japan and Russia will also promote their own strategies based on hybrid geopolitics in order to tackle the contradiction between their internal stability and the uncertainty in securing their positions in the international system. Given this, Northeast Asia will witness competition in a variety of areas, such as the existing borders, new virtual borders, and future frontiers of interest, and states are likely to cooperate and confront each other on a case-by-case basis. Given these regional dynamics, the concern is that not only the prospects for North Korea’s denuclearization will be much bleaker, but in some cases Pyongyang may even resume “strategic provocations.”

In Europe, chaos will become worse. Although it is not certain whether Brexit will actually happen in 2020, its impact on triggering a U.K.-EU dispute and re-igniting conflict between Britain and Northern Ireland will remain powerful. Indeed, the clash between France and Germany over the future role of NATO may further weaken the EU’s solidarity which was already diminished by Brexit.

Meanwhile, in the Middle East, even though the decline of the United States and the return of Russia have featured prominently, the problem is that neither development is likely to contribute to regional stability. Rather, in the struggle over the new geopolitical map, the advances of Turkey, Iran, and Saudi Arabia will exacerbate instability across the region.

In Southeast Asia, ASEAN’s dilemmas will increase amid ongoing U.S.-China strategic competition. ASEAN tried to establish its own position in 2019, but in the process demonstrated its potential as a collective actor and also its power limitations. Therefore, it will be interesting to see what strategic calculations and policy prescriptions ASEAN will make as Vietnam assumes the chair in 2020.

Despite the rise of hybrid geopolitics, emerging security challenges will guarantee cooperation and collaboration among states. In 2020, states will continue to ostensibly work towards “global governance.” However, we will witness the limits imposed by national interests of individual states repeat themselves even in the area of emerging security. That is, the uncertainty of hybrid geopolitics will extend to emerging security issues as well. While all states will stress the need for cooperation on global public goods and common causes of concern, individual national interests and the geographic positions of states will pose a formidable challenge to this.

The more such features of hybrid geopolitics manifest themselves, the more difficult Korea’s choices will be in 2020. If 2019 offered a vague forecast of the risks and concerns of the new geopolitics, then 2020 exacerbates the dilemmas Korea will face in a hybrid geopolitics world. If South Korea does not abandon its current one-way inter-Korean policy or come up with a new idea, then there is a risk that South Korea’s regional and international position will be seriously weakened.

Northeast Asia in 2020: Intensifying Hybrid Geopolitics

The features of hybrid geopolitics discussed thus far will become even clearer in 2020. States will need to address a greater variety of issues than just traditional geographical borders and also deal with the emergence of new “virtual borders” such as new science and technology frontiers, the Internet of Things, and overseas diaspora communities. As the arena of great power competition expands, other countries will increasingly have to bear the burden and fallout. Major states such as the United States, China, Russia and Japan will struggle to form a new strategic alignment that is different from the one in the past.

Against this background, Chinese and Russian intrusion on the Korea Air Defense Identification Zone (KADIZ) will recur or become even more frequent in 2020. This will reflect the approach of Korea’s neighbors towards managing rather than solving issues on the Korean Peninsula. As a result, the prospects for meaningful progress on the denuclearization of North Korea will be slim. South Korean strategic thinking will deepen in light of the major powers’ logical contradictions. A case in point is President Trump’s demands for greater defense burden-sharing from U.S. allies in its strategic competition with China, whilst championing a non-interventionist foreign policy.

South Korea may not take advantage of ambiguity in 2020. Instead, it will face a multi-faceted challenge. Unlike in the past when great power competition at the global level impacted Northeast Asia and the Korean Peninsula, in 2020 tensions in this region may trigger conflicts at the international level. To ensure its security in the era of hybrid geopolitics, South Korea must adjust its foreign policy that has been focused primarily on improving inter-Korean relations and convince neighboring countries of its leverage against Pyongyang. Without this leverage, South Korea will go through a much tougher time in 2020.

North Korea in 2020: More Provocations, Fading Denuclearization

The year 2020 will be a difficult year for inter-Korean relations. North Korea will continue to pursue its own path while severely criticizing Seoul and Washington. Domestically, it will put emphasis on managing the economy through its own efforts. With regards to its foreign policy, North Korea will seek to break out of its diplomatic isolation by improving relations with China and Russia. On this basis, North Korea will confront the United States and adhere to its own definition of “denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula” in which the South Korea-U.S. alliance and U.S. troops in South Korea are the key obstacles to achieving denuclearization. Hence, U.S.-North Korea relations and inter-Korean relations will inevitably worsen in 2020.

North Korea thinks inter-Korean relations are subordinate to its bilateral relations with the United States. In this sense, Pyongyang will continue to show an attitude of indifference towards Seoul unless significant progress in U.S.-North Korea talks is made in 2020. Under such circumstances, it would be difficult to imagine unified Korean teams for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, and inter-Korean exchanges both at the government and private levels are likely to be cut off.

More importantly, there is a high possibility of North Korea’s military provocations in response to little progress in the U.S.-North Korea talks. By carrying out military provocations, Pyongyang may pass the buck to Seoul and accuse it of its failed mediating role. Consequentially, in 2020 we may witness a revival of tensions between the two Koreas rather than a progress in their relations.

Nuclear North Korea will adopt and carry out a new strategy. North Korea may pursue a hybrid strategy combining cyber warfare with information warfare. It may also intervene in South Korea’s domestic politics indirectly by causing internal conflict in the South. Regarding denuclearization, Pyongyang will refuse to go into the details and insist on sanctions relief for partial and symbolic denuclearization steps of its own. It will also steadily continue to conduct missile tests and improve its delivery capabilities. Further nuclear tests are unlikely considering that it has already accumulated enough nuclear technology. The current atmosphere in North Korea nuclear talks are transforming from denuclearization talks into disarmament talks, just as Pyongyang intended. In 2020, we may find ourselves living with little hope for the denuclearization of North Korea.

The United States in 2020: Conflict on All Sides

U.S. foreign and defense policy in 2020 will not show many changes. U.S.-China relations will continue their confrontation. The U.S. Congress has shown growing bipartisan support for a more aggressive approach toward China. U.S.-Russia relations will remain confrontational for the time being in line with U.S.-China relations. The cracks in the trans-Atlantic relationship, already apparent, will continue in 2020. In the Middle East, the United States will push for new negotiations with Iran while re-applying sanctions. In Asia, U.S.-Japan relations will not be smooth, especially with defense cost-sharing negotiations set to take place in 2020. And unless North Korea conducts a major provocation, due to more urgent domestic issues the Trump administration is likely to put approach the North Korean nuclear issue calmly and slowly.

There are three important issues in South Korea-U.S. relations in 2020. The first is Korea-U.S. defense cost-sharing deal. The second is the transfer of wartime operational control. There is a high likelihood of disagreements between the two countries over whether the conditions for the transfer have been met. In this regard, the relationship between a future Korean-led Combined Forces Command and discussions over a reinvigorated United Nations Command could also increase the differences between the two sides. Lastly, the U.S. continues to expect the South Korea-U.S. alliance to look in a future-oriented direction and also for South Korea to actively participate in its Indo-Pacific Strategy.

Figure 4. Korea-U.S. Defense Cost-Sharing Negotiations Break Down

Source: Yonhap News.

China in 2020: Transforming Crisis into Opportunity

In 2020, the Chinese Communist Party will strive to foster internal unity and solidarity by exercising strong leadership. Another main goal of the Chinese leadership in 2020 will be sustaining economic growth with a growth rate target of six percent and also making its image as a rival to U.S. protectionism. Externally, China will strengthen its relations with Russia through comprehensive strategic cooperation on par with an alliance to balance against the United States. In 2020 U.S.-China competition will turn into a full-scale competition. China is now preparing for a global contest with the United States “to the very end.” With Taiwan’s presidential elections scheduled for January 2020, management of cross-Strait relations will also be an important political and diplomatic task.

In 2020, South Korea-China relations will see improvement as the two sides move past the THAAD dispute. With President Xi Jinping likely to visit Korea in 2020, most Chinese economic retaliation over the THAAD deployment is expected to be lifted. But, above all, the main reason for instability in South Korea-China relations in 2020 will be the continued U.S.-China conflict. A worsening of U.S.-China relations is likely to subordinate South Korea-China relations, and Korea may face a tougher dilemma to choose from both countries.

Japan in 2020: Leaving a Domestic and International Legacy

Japan will attempt to use the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympics as a diplomatic achievement to cement its claim to geopolitical leadership and a leading role in the regional order. Although Prime Minister Abe’s administration has actively cooperated with the U.S.-led liberal international order, bilateral frictions will also be inevitable on defense cost-sharing as well as trade deals. There is also room for further improvement in Japan-China relations in an effort to minimize the impact of U.S.-Japan tensions and to safeguard against changes in the international order. As Japan’s longest serving prime minister, Prime Minister Abe’s domestic efforts to leave a legacy will be focused on the final settlement of Japan’s post-war diplomacy and constitutional revision. As part of this effort, the improvement of North Korea-Japan relations should also be kept in mind. Regarding constitutional revision, even if the original goal of revising Article 9 of the constitution is unsuccessful, even a partial revision would be seen as a part of his legacy.

On November 22, 2019, South Korea’s announcement of the conditional suspension to the termination of the two sides’ General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA) eased the ongoing tensions between Seoul and Tokyo. There has been rising expectation of an improvement in bilateral relations. However, key issues such as GSOMIA, export controls and the forced labor issue will continue to hamper rapprochement. Tensions will escalate again, however, if the Abe administration provokes sensitive issues such as radioactive water leaking into the Pacific from the Fukushima nuclear power plants and the use of the Rising Sun Flag at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. Above all, if Japanese corporate assets in Korea seized by plaintiffs in the forced labor case are executed, the Korea-Japan relationship is likely to deteriorate. A return to conflict will make it hard to control anti-Japanese sentiments in Korea and confrontation between the two countries.

Europe in 2020: From Crisis to Even Greater Crisis

Great Britain’s path to Brexit in 2020 remains unclear. Even if Brexit takes place, it will be the beginning of a new chaos. Far-right populist parties, which made big gains in the 2019 European elections, will also be an important factor in 2020. At the May 2019 European Parliament elections, a new far-right coalition composed of nationalist, populist and Eurosceptic political parties called “Identity and Democracy” won a large proportion of votes and is set to be an important player in European affairs.

Source: Yonhap News.

On foreign affairs, debate will continue between France’s proposal for a European Army to replace NATO and Germany’s call for strengthening European defense and security cooperation as a complement to NATO. French President Emmanuel Macron made the proposal as a rejection of the Trump administration’s unilateral agenda ahead of presidential elections. But the differences between France and Germany are unlikely to be resolved in the short term. Europe appears to be heading for another chaotic year as it grapples with challenges both at home and abroad.

Russia in 2020: Domestic Stability but Uncertain External Future

President Putin is the key variable in Russia’s imperial ambitions. His firm rule over Russia will continue in 2020 and with it his dreams of empire. As long as the current party structure persists between the hegemonic control of his ruling United Russia party and the array of smaller opposition parties, it will be difficult to expect any challenges to the status quo. Given that Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev remains Putin’s designated successor, the Russian dream of empire appears to be in safe hands. Little effort is being made to search for another successor or change the constitution.

In 2020, Russia will continue on its current path as a great power drawing on its domestic political stability. Russia will further expand its influence in the Middle East, but its weak domestic and material bases of support will hamper its ambition. But, for near future at least, Russia will still play a great power role on the world stage as both a competitive partner of China and a rival of the United States.

In Northeast Asia, Russia will remain an ineffective mediator on behalf of North Korea having gained the regime’s favor. South Korea’s New Northern Policy will continue in 2020 in name only. Russia will reach out to South Korea to play host to inter-Korean dialogue while simultaneously supporting North Korea’s behavior. South Korea will try to ease tension in Northeast Asia by responding to the Russia’s offer with little concrete success.

ASEAN in 2020: The Vietnamese Factor and U.S.-China Rivalry

Southeast Asia will remain generally stable domestically in 2020. Elections are due in Singapore and Myanmar, but the chance of a surprising result is slim. But there will be at least one ripple in this otherwise tranquil ASEAN. Vietnam will assume the ASEAN Chairmanship in 2020 and all eyes will be on how it leads over the South China Sea issue. ASEAN will also take stock and review the performance of the ASEAN Community since its launch five years ago.

The U.S.-China geopolitical conflict will remain a factor for ASEAN in 2020. Add to this the uncertainty surrounding the upcoming U.S. presidential election as well as whether President Trump will be re-elected, or if his impeachment is upheld, and the potential impact on ASEAN could be large. However, the fluid situation leading up to the U.S. presidential election means that ASEAN will take a “wait-and-see” approach towards the United States and China.

The South Korean government’s New Southern Policy will enter in to the second phase in 2020. It will be two years since the announcement of the policy and it also marks the turning point of the Moon administration’s five-year term. In its first half, the New Southern Policy delivered clear results. President Moon visited all 10 ASEAN countries within two years, which was a first for a Korean president and affirmed the Korean government’s commitment to the policy. The third ASEAN-Korea Commemorative Summit was also held at the end of 2019. Now what lies ahead for the New Southern Policy 2.0 is delivering tangible and visible achievements that will sustain the policy.

The Middle East in 2020: U.S.-Sparked Reorganization of Geopolitics and Continued Unrest

The Middle East in 2020 will see Russia’s illiberal order consolidated as it fills the vacuum of U.S. withdrawal. As the U.S.-Iran confrontation turns into a prolonged tit-for-tat skirmish, the likelihood of an actual war breaking out will decline. This is because the upcoming U.S. presidential election, Iran’s economic plight, and the U.S. abandonment of allies and partners will make war a substantial burden for both sides. The credibility of the United States dropped as it undermined the very value of alliances in the Middle East. Russia, Iran and China filled the void left by the United States to protect patrons such as Syria to the very end. Turkish President Erdogan has emphasized Turkish nationalism, neo-Ottomanism, and Eurasian policies while strengthening his one-man rule and electoral authoritarianism as he moves closer to Russia.

Massive anti-government protests in Iraq, Lebanon, Egypt and Iran at the end of 2019 will continue to fan further domestic unrest. After the 2011 Arab Spring democratization uprisings, citizens across the Middle East were more likely express their grievances against government incompetence and corruption than ever before. The sudden collapse of dictatorships across the Middle East is still underway, but there is a low chance that they will lead to democracy. Revolution or regime collapse happens accidentally when the dictator misses a moment, but stable democracy never comes by chance.

New Security Global Governance Based on Mutual Benefit

Emerging security threats are causing ever greater amounts of damage, such as climate change-related extreme weather events, natural disasters, fine dust pollution, cyber terrorism, infectious diseases affecting humans such as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) or animals such as African Swine Fever (ASF), the rise and fall of cryptocurrency markets, and other threats. But it is hard to predict whether these same threats will emerge again in 2020 or whether even newer threats may appear with the potential to wreak yet great damage. In addition, the effectiveness of international cooperation in coping with new security issues has been called into question as global governance has been unable to provide solutions, leaving states to fall back on self-help efforts.

One of the characteristics of these new security threats is that micro-level problems to individuals’ day-to-day lives unrelated to the individuals’ nationalities are amplified in certain situations, becoming a macro-level national security issue. While individual countries have to strengthen international cooperation in coping with the new security threats, at the same time, they have to consider available national resources and put priority in coming up with country-specific policies and measures given the impacts of the threat at a national level. That is because international cooperation is not a justification but a reasonable choice for the pursuit of mutual benefit.

A Lull in the U.S.-China Trade War and Recovering World Trade Order in 2020

For the United States, 2020 will be the year of the presidential election. President Trump does not have to disrupt the U.S. economy to win re-election. The U.S.-China trade war will only be discussed again after November 2020, assuming President Trump is re-elected. Until then, it will enter a truce period during the election cycle.

On the South Korea-Japan trade war, Japan will emphasize that there is no effect on Korea’s global trade by selectively giving export permission to Korea during 2020, while the World Trade Organization (WTO) process is suspended. In other words, the trade war will not escalate while talks on export management policies continues.

Once the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) is signed in 2020 it will become one of the global economic order’s two largest mega free trade agreements together with the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) signed on December 30, 2018. The fact that RCEP was actually completed despite the fierce U.S.-China trade war in 2019, suggests that the multilateral international trade order will recover in 2020 as the U.S.-China trade war enters a truce.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter