Introduction

There are numerous critical assessments of President Moon Jae-in’s foreign policy halfway through his single five-year term.1 Fair policy assessments, however, are difficult to make in a short period of time. Part of the reason for this has to do with the fact that policy outcomes are often realized long after the president’s term is over. Rather than trying to assess President Moon’s foreign policy performance and outcomes, we examine what the president has said and done during his first three years. In particular, we analyze all of President Moon’s public statements and his travel data to assess his orientation and priorities in foreign policy.

What Moon Said

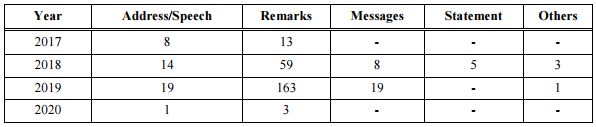

The first set of data we will examine is President Moon’s public statements. These include public address, remarks, messages, statements, and press conferences. The breakdown by year is shown in Table 1. Not surprisingly, the first year was less than a full calendar year so the number of public statements we observe was significantly lower than in 2018.

Table 1. Public Statements by President Moon, 2017~202

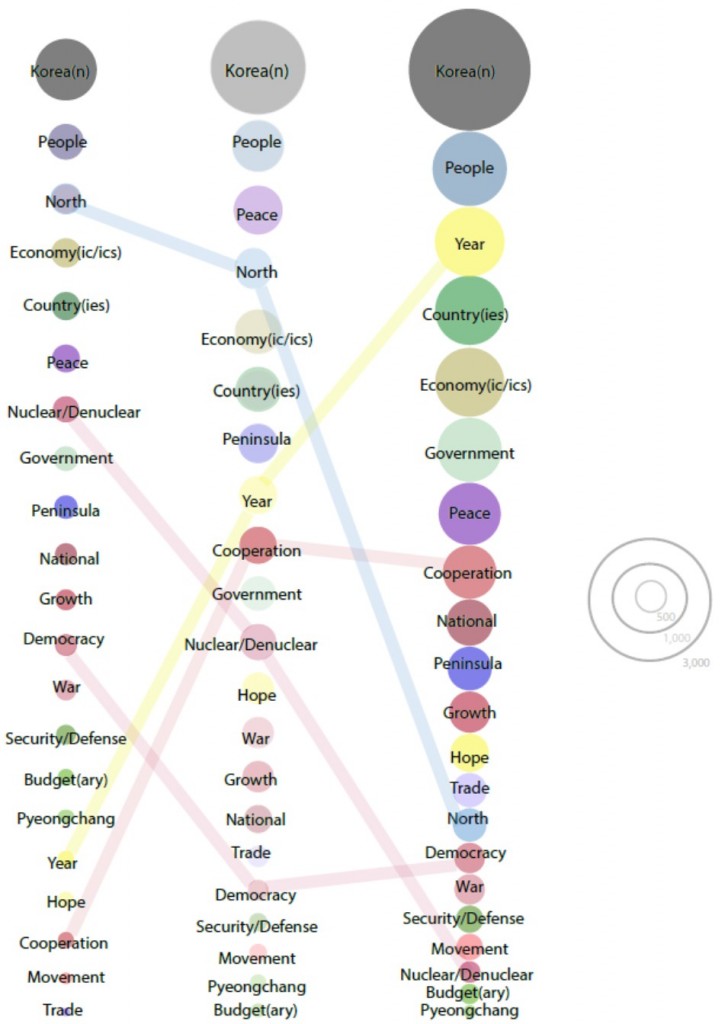

As shown in Figure 1, frequent keywords mentioned by President Moon are grouped according to year. One common theme that emerges every year is nationhood or national identity as shown by the two most frequent keywords “Korea(n)” and “people.” This is in line with the president’s focus on the concept of “woori minjok” or ethnicity and the Korean “peninsula.” The reference to national identity is a means by which the administration can justify an inward-looking policy that attempts to bind the two Koreas. It is not at all surprising then that minjok was the most frequent word used by both Kim Jong-un and President Moon during the three inter-Korean summits in 2018.

The frequent reference to national identity also serves to justify the Moon administration’s approach to managing relations with Japan. For instance, the Blue House announcement in August 2019 to terminate the General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA) was described by Shin Gi-wook as “nothing less than the head on collision of right-wing Japanese nationalism and left-wing South Korean nationalism.”3 Others have described the relations between Seoul and Tokyo as “profound issues of identity.”4

Figure 1. Most Frequent Keywords from President Moon’s Public Statements, 2017~19

2017 2018 20195

While the administration has placed a lot of emphasis on the Korean identity, there are some noticeable shifts in how it characterizes inter-Korean relations over time. For instance, we notice more frequent appearance of the word “cooperation” in President Moon’s public statements during 2018 and 2019 than 2017 and less frequent mention of the word “north” in 2019 than in 2017 and 2018. This pattern is understandable given that the administration has worked very carefully to frame the North Korean issue around inter-Korean cooperation and less on North Korea itself. Moreover, words like “peace” and “cooperation” resonate with the centerpiece of the administration’s foreign policy platform – “peace and prosperity.”6

This also explains the decline in the occurrence of the word “nuclear” or “denuclearization” in each subsequent years after 2017. In spite of many diplomatic activities throughout 2018 and 2019, North Korea has not made meaningful moves towards denuclearization. The fact that the president places less emphasis on “denuclearization” in 2019 than in 2018 or 2017 is an accurate reflection of this reality.

Similar observations can also be made about concepts such as “democracy” or “national security” and “defense.” While these topics are highlighted in President Moon’s public statements, they are not as important as other topics, which more accurately reflect President Moon’s policy priorities and orientation. For instance, domestic concerns such as the “economy” or “growth” appear to be more pressing for President Moon than issues related to political liberalization and national defense.

Where Moon Went

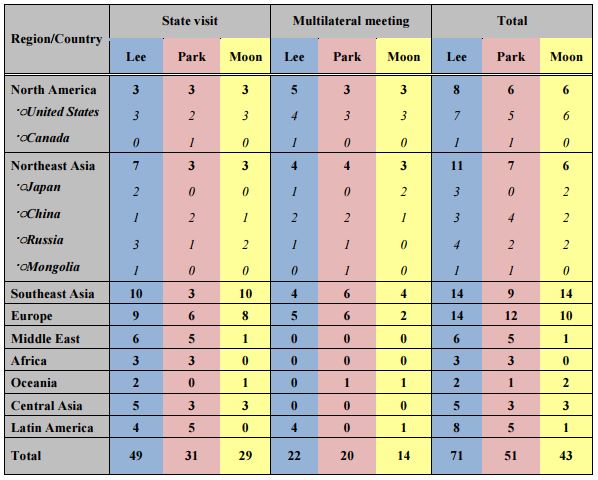

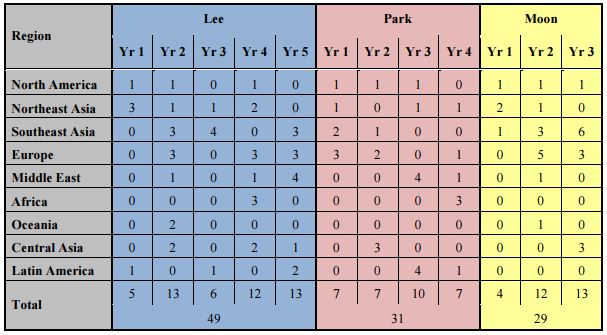

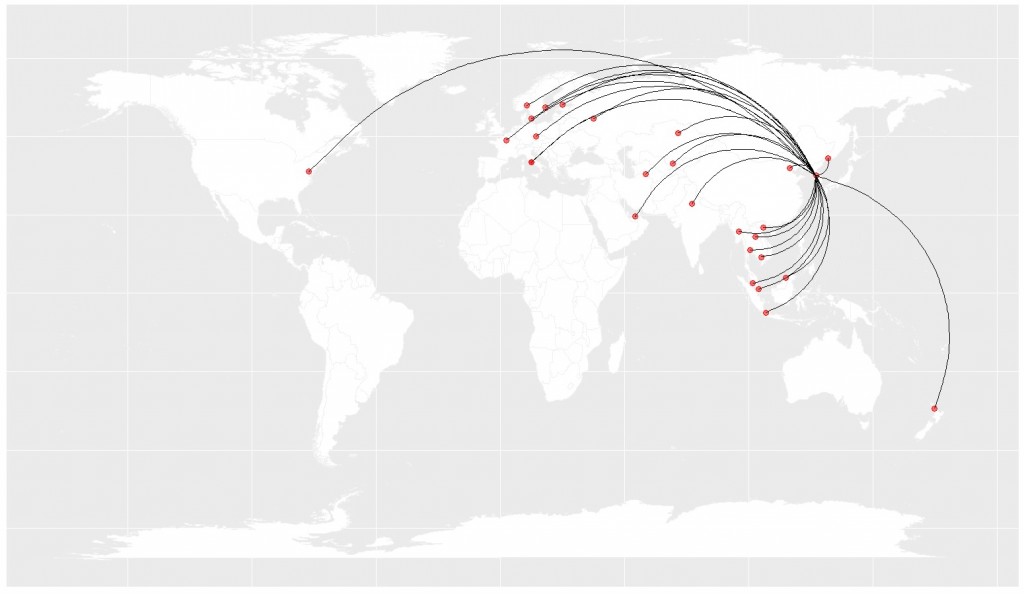

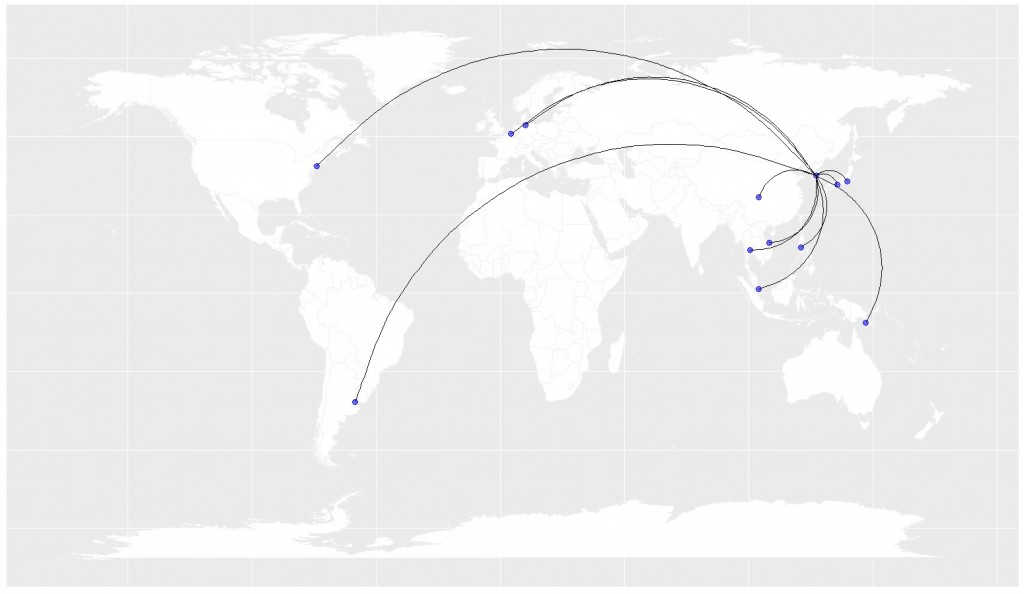

In this section, we trace President Moon’s footsteps around the world to confirm what we know about his priorities and orientation. Based on his public statements, we gather that President Moon is decidedly more inward-looking and focused on the Korean peninsula. If true, we should expect to see less frequent trips abroad than his predecessors. However, this is not the case. We find that President Moon is on pace to be more active in his foreign travels than President Park Geun-hye. So far, President Moon has taken just as many trips abroad on official state business as President Park during her term. By the end of his fifth year, President Moon is likely to have participated in just as many, if not more, multilateral meetings than President Park or President Lee Myung-bak.

By our count, President Moon has made 43 official visits to 32 countries since he took office in May 2017 (The US (x6), Japan, China, Russia, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam (x2)). Of these, 14 were to South and Southeast Asia. This accounts for approximately 33% of President Moon’s entire travels. This is markedly higher than that of his immediate predecessors, Lee (20%) and Park (17%). It provides an important insight into President Moon’s foreign policy priority.

Table 2. Travel Destinations by Presidents, 2008~197

During his state visit to Indonesia in November 2017, President Moon officially unveiled the “New Southern Policy” (NSP), emphasizing the strategic importance of ASEAN to South Korea. President Moon seems intent on diversifying South Korea’s diplomatic ties and developing an opportunity for strengthening economic cooperation with the NSP countries (i.e., ASEAN and India). In 2018, the Foreign Ministry established a separate bureau that deals exclusively with ASEAN-related affairs and the government launched a presidential committee on New Southern Policy. During a cabinet meeting in November 2019, President Moon states bluntly that his administration has distinguished itself by focusing on areas outside of “the four powers surrounding the Korean Peninsula.”8

Table 3. State Visits by Presidents, 2008~2019

Figure 2. President Moon’s State Visits, 2017~19

Figure 3. President Moon’s Attendance to Multilateral Meetings, 2017~19

In September 2019, President Moon fulfilled his pledge to visit all ten ASEAN member states. Given that neither Presidents Lee and Park have visited all ten countries during their presidency, this act alone illustrates the seriousness of the current administration’s interest in NSP. Part of the reason for this push towards South and Southeast Asia is also linked to Washington’s call for South Korea’s participation in the Indo-Pacific strategy. President Moon obliged by announcing in June 2019 South Korea’s interest in looking for “harmonious cooperation” between NSP and the Indo-Pacific strategy. As the first step in this direction, South Korea and the US issued a “Fact Sheet” in November 2019 to outline areas of complementarity between NSP and the Indo-Pacific strategy.

It is yet unclear, however, whether President Moon’s commitment to NSP is a full-throated endorsement of the Indo-Pacific strategy. While China has not been mentioned as much in his public statements, President Moon also emphasizes the importance of his New Northern Policy (NPP). President Moon appears to see no reason why NSP and NPP cannot both accommodate China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Indo-Pacific strategy. President Moon, for instance, has mentioned the signing of RCEP within the context of NSP and the South Korean government.9

The United States and Europe

Given that the US-Sino strategic competition is likely to become more contentious in the future, South Korea will find it difficult to not choose sides between these two great powers. The recently announced Phase I deal only appears to be a temporary truce in the ongoing trade war between Washington and Beijing. Most observers recognize that the strategic competition between the US and China will continue to deepen in the future given the structural realities of this relationship. For the moment, President Moon appears closer to the United States than China.

As of December 2019, President Moon has visited the US six times, while both Lee and Park traveled to the country only four times during their first three years in office. The US is critical to President Moon’s “Korean Peninsula Peace Process.” For President Moon, the end to the Korean War and the establishment of a permanent peace regime requires the United States and North Korea to reach an agreement. It is also difficult to deny the importance of the ROK-US alliance as far as South Korea’s national security is concerned. Moreover, as the above discussion suggests, President Moon has also declared an interest in promoting synergy between his New Southern Policy and the US Indo-Pacific strategy.

President Moon’s trips out to Europe is also tied to his desire to expand inter-Korean cooperation. More specifically, the purpose of his visits to the region during 2018 and 2019 was to gain European support for loosening sanctions on North Korea. It is unfortunate, however, that he failed to gain traction on this matter. It would have been more productive for the president to have emphasized other areas of cooperation with Europe, such as climate change, trade, human rights, energy, and technology.

Northeast Asia

Our data shows that President Moon has visited Northeast Asian countries six times so far. This is comparable to previous administrations; however, a closer examination reveals the difficulty that South Korea is having with both China and Japan.

President Moon has visited Japan only twice in his term, yet none of these were bilateral state visits. There is no secret to the reality about South Korea’s complicated relationship with Japan due to the fall out over historical matters. Trade and security relations have also been impacted due to the retaliatory measures that both Tokyo and Seoul have levelled against each other during the second half of 2019. While both countries have resume dialogue on all outstanding issues, it is yet unclear how the two sides will settle the fundamental disagreements regarding numerous historical and trade issues.

Relations with China is also challenged given the cold reception that President Moon received during his state visit to Beijing in December 2017. China appears unwilling to turn the chapter on South Korea’s basing of the US-controlled Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missile system in 2017. Despite Moon administration announcing its so-called “Three No’s”10 policy, South Korea has been unable to mend its relations with China. Things look to get even more complicated as China grows weary over the possibility that South Korea will base US-controlled intermediate-range ballistic missiles on the Korean peninsula. There is a potential opportunity in redefining this relationship as President Xi is expected to visit Seoul in the coming months.

Middle East, Africa, and Latin America

The most striking difference between President Moon and his immediate predecessors is the marginal interest in Latin America, the Middle East, Oceania, and Africa. Moon has only visited Argentina and the United Arab Emirates from these regions. Only one of these were bilateral state visit. The other was for the G20 Summit. It is still too early to conclude whether President Moon will make a trip to these areas, but these are certainly very important from a national interest point of view. South Korea relies heavily on the Middle East for most of its oil and natural gas. South Korea’s total investment in Latin America is over $8 billion and trade is over $50 billion. As the region becomes more prosperous, South Korea’s relationship with this region will only grow stronger. The US-led Indo-Pacific strategy also encompasses the Oceania and the South Pacific. South Korea would be making a bold statement by reaching out to this region to further solidify its commitment to the New Southern Policy. Most certainly, a more diversified diplomacy that President Moon has emphasized during his presidency would necessarily involved broader commitments to these regions.

Conclusion

While it is too early to pass judgment on President Moon’s foreign policy, his words and deeds reveal a lot about his policy priorities and orientation. Our analysis of President Moon’s statements, for instance, reveals that he cares deeply about issues related to national identity and the Korean peninsula. In fact, the president appears especially interested in expanding inter-Korean cooperation and deemphasizing denuclearization and democratic values. It bears mentioning, however, that democratization and strong national security have been the bedrock upon which South Korea has built its Miracle on the Han during the latter half of the 20th century. Without placing greater priority on these objectives, it is unclear how South Korea will continue to enjoy the benefits of peace and prosperity.

Outside of the Korean peninsula, the president appears to value South Korea’s interests in South and Southeast Asia as well as the bilateral relationship with the United States. As our discussion suggests, this is motivated, in part, by the administration’s interest in promoting its New Southern Policy and inter-Korean relations. However, President Moon also admitted that South Korea has more to gain from having a more global outlook that moves beyond South and Southeast Asia as well as North America. Growing opportunities in other parts of the world cannot be ignored. Issues that touch on emerging technology, climate change, and human rights are just as crucial to expanding South Korea’s national interest as are Korean peninsula related issues. This is especially true as the US role internationally may continue to diminish in the near future. South Korea should seek to strengthen its ties with other countries and seek opportunities beyond the Korean peninsula. A more diversified diplomacy that emphasizes a global agenda would help to mitigate the risks associated with a more retrenched US position.

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 1. 동아시아연구원, “[EAI 정책토론회] 문재인 정부 중간평가: 여론조사 및 후반기 정책과제,” 2019년 11월 5일. “[임기 반환점] ⑦ 숨 가빴던 한반도 외교전 ‘일단 멈춤’…다시 힘낼까,” 연합뉴스, 2019년 11월 3일. “한미동맹 ‘균열’•남북관계 ‘교착’… ‘北중심 외교’ 禍 자초,” 문화일보, 2019년 11월 8일.

- 2. Cheong Wa Dae, “Speeches & Remarks,” (https://english1.president.go.kr/BriefingSpeeches/Speeches); the data for 2020 is incomplete with data only reflecting public statements by President Moon up until January.

- 3. Jung H. Pak, ‘Why South Korea and Japan fight so much about trade’, East Asia Forum (October 7, 2019).

- 4. Ibid.

- 5. Public statements from 2019 includes New Year address from 2020.

- 6. The first line in the 2019 government White Paper on Korean Unification states that “the Moon Jae-in government set ‘peace and prosperity on the Korean Peninsula’ as the national objective…” [emphasis added]. The Panmunjom Declaration signed on September 11, 2018 is also entitled “Panmunjom Declaration for Peace, Prosperity and Unification on the Korean Peninsula” [emphasis added].

- 7. For data on international trips made by President Moon, see Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Presidential trips,” (https://www.mofa.go.kr/www/brd/m_20053/list.do). For data on international trips made by President Lee, see Presidential Archives of Korea Website, “Summit diplomacy,” (http://17cwd.pa.go.kr/kr/diplomacy/2012/index.html). For data on international trips made by President Park, see Presidential Archives of Korea Website, “Summit diplomacy,” (http://18president.pa.go.kr/news/overseasTrip/2016/trip2016.php).

- 8. Opening remarks by President Moon Jae-in at Cabinet Meeting. November 12, 2019.

- 9. 양평섭, 박영호, 이철원, 정재완, 김진오, 나수엽, 이효진, 조영관. 2018. 「신흥국의 대중국 경제협력 전략: 일대일로 이니셔티브 대응을 중심으로」. 경제〮인문사회연구회 중국종합연구 협동연구총서 18-67-09. 대외경제정책연구원.

- 10. 1) no additional deployment of the THAAD, 2) no participation in the American missile defense network, and 3) no pursuit of a trilateral military alliance with the United States and Japan

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter