Introduction

A two-day state visit by President Xi Jinping to South Korea starting on July 3 received an enormous amount of attention in the region. The United States and Japan watched the summit somewhat cautiously with the primary concern being how South Korea would react to China’s aggressive wooing. North Korea launched missiles prior to President Xi’s visit and, more importantly, began negotiations with Japan on the issue of abductees and the economic aid package that would be offered in exchange. For South Korea, the most important question was if China was ready to take serious steps toward ending North Korea’s nuclear program.

In its previous report on attitudes towards China issued just before the July 2014 summit, the Public Opinion Studies Program at the Asan Institute for Policy Studies found that public opinion toward China was at its most positive point since Asan began tracking those numbers. However, it highlighted that there was also an underlying wariness of China’s rise. This Issue Brief serves as an update to that report, highlighting changes—and sometimes the lack thereof—in public attitudes following the second Korea-China summit.

Public View of the Summit

In the run up to the second bilateral Korea-China summit, there was wide speculation about what the deliverable of the summit would be. One rumor posited that China would make the substantial change from supporting the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula to supporting the denuclearization of North Korea specifically. Another angle stated that the visit of President Xi himself was the deliverable. Although the press coverage before the summit was generally favorable, it was less positive than the coverage during the run up to and following the first summit in June 2013.

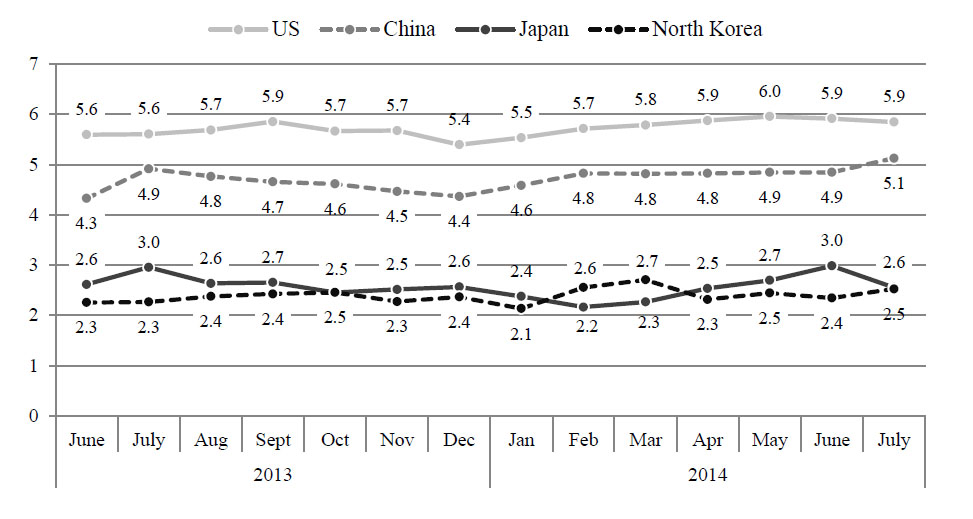

The end result was a small increase in the favorability of China, from 4.9 to 5.1 (Figure 1). However, it should be noted that the results for July were taken from a survey conducted July 1-3—just prior to the summit—and thus do not reflect satisfaction with the results of the summit itself. Instead, they reflect anticipation of the summit and its outcomes, but there are still lessons to be drawn.

Figure 1: Country Favorability

Following the summit there was likely little increase from the 5.1 registered in the survey conducted just prior. This is primarily due to two factors. First, Korea-China relations were at a much different point at the time of the first summit. The bilateral relationship was one that had been left untended during the presidency of Lee Myung-bak and President Park’s repairing of that relationship from the beginning of her term was hailed as a success. This is reflected in the sharp one-time increase in the favorability of China from June to July 2013. However, by mid-2014 it was no longer enough to simply have good relations. In the lead up to the second summit, the Korean media began to focus on outcomes.

Second, media coverage of the actual outcomes following the July 2014 summit was not overwhelmingly positive. While there were some positives, China did not alter its support for denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula. There was an official upgrade to the Korea-China relationship, but this is a nuance not fully fleshed out by the media and not fully understood by the public.

While the favorability of China may have increased slightly from the 5.1 mark on the eve of the summit, the total increase likely fell short of the 0.6 jump seen after the 2013 summit. Nonetheless, the favorability of China is now at the highest point since Asan began tracking the number, and marks the first time that any country included in the survey besides the United States surpassed 5.0 on the zero to ten scale. Given the stability of China’s favorability since February 2014, there will likely be little decline in the near future barring a significant hiccup in Korea-China relations.

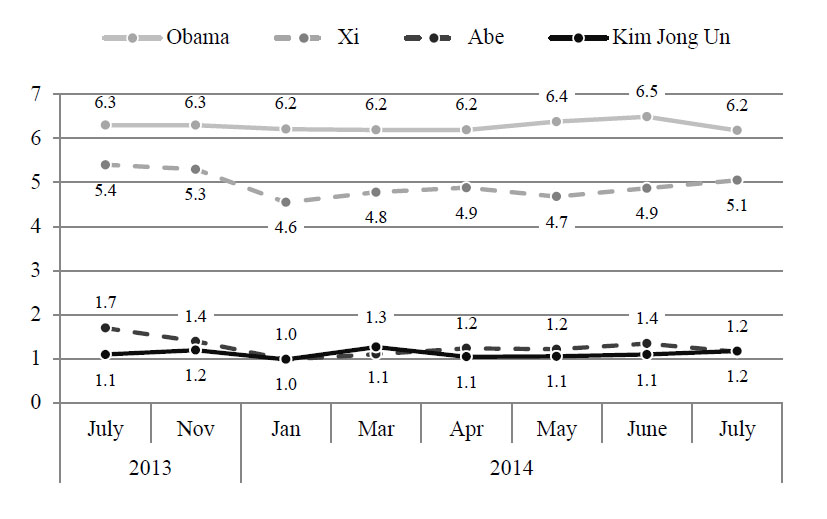

Like country favorability, there was also a small uptick in the favorability of President Xi in the days just before the summit (Figure 2). However, it remains shy of the previous high which was established in the initial measurement following the 2013 summit.

Figure 2: Leader Favorability

This measurement, too, is unlikely to have experienced a significant increase following the summit. While President Xi was well received, the outcome was not all that was hoped for, and rather than focusing on the denuclearization of North Korea his remarks at Seoul National University about Japan garnered the most attention. This was not the focus that the Korean public had hoped for before the summit. As noted in the report issued by the Asan Institute in the days just prior to the summit, just 12.8 percent thought that dealing with Japan’s historical revisionism should be the top agenda item for the Korea-China summit. A clear majority (53.8%) cited the North Korea nuclear problem. With the lack of movement on this issue, a more significant bump in the favorability of President Xi seems unlikely.

China, the Economic Partner

The summit also brought a significant change to the Korean public’s attitude toward China in the area of economic cooperation. One result of the July 2014 summit was that the two leaders agreed to conclude FTA negotiations within the year. This was widely publicized and well received.

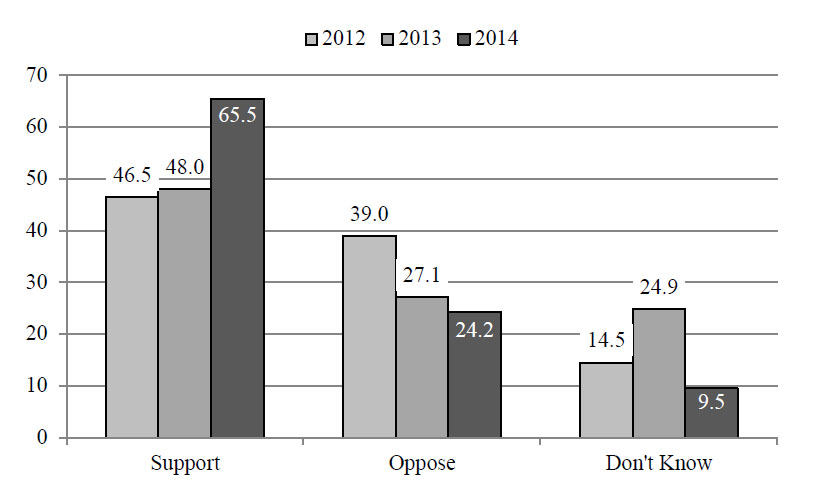

In both 2012 and 2013 less than 50 percent of the public approved of a Korea-China FTA. Of course, this may be partially related to the public’s past negative views of FTAs in general and not specifically related to China. Regardless, the public is now widely in support of a Korea-China FTA with 65.5 percent stating as such (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Support for a Korea-China FTA

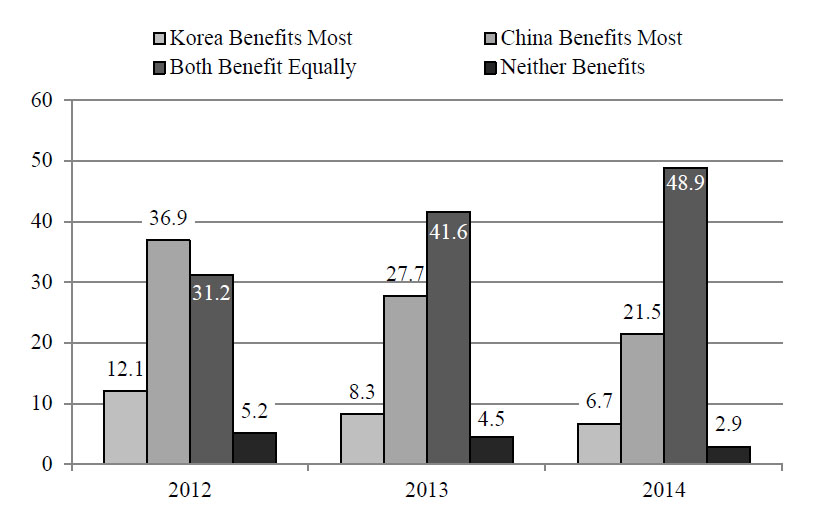

It is especially notable that the percentage that sees an FTA between Korea and China as mutually beneficial continues to increase. When asked about perceived benefits of such an FTA in 2012, a plurality (36.9%) stated that China would be the prime beneficiary (Figure 4). Only 31.2 percent stated both countries would benefit equally. Those numbers changed in 2013, with 41.6 percent citing it as mutually beneficial. This time, however, a near majority (48.9%) stated that the FTA would be beneficial to both countries. Clearly, the public has high expectations for the Korea-China FTA.

Figure 4: Perceived Benefits of a Korea-China FTA

A Sophomore Slump?

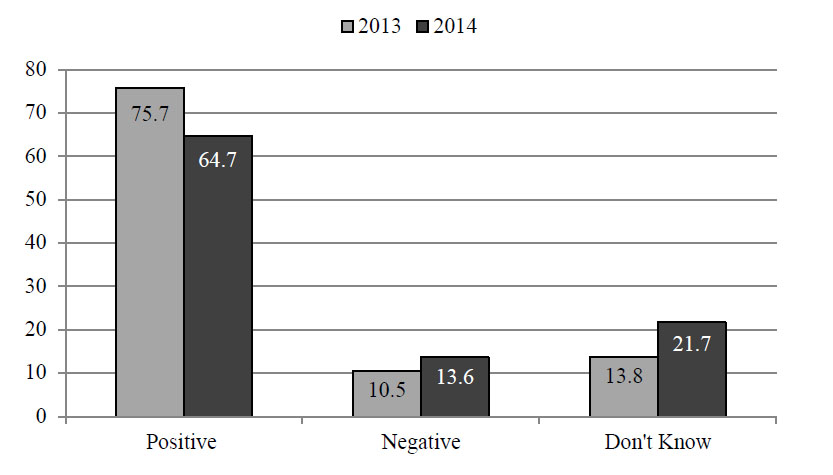

On the surface, it seems that relations between South Korea and China cannot get much better. The summit seems to have been a success, with 64.7 percent positively evaluating it (Figure 5). This is a considerable majority. However, following the first summit in 2013 75.7 percent assessed it positively. While negative assessments increased slightly from 2013 to 2014—from 10.5 percent to 13.6 percent—there was a significant increase among “don’t knows”, from 13.8 percent in 2013 to 21.7 percent in 2014.

Figure 5: Assessing the Korea-China Summits

The decline likely stems from a shift by the Korean public to focus on outcomes of the improving Korea-China relationship, rather than merely having good relations. It is understandable that the most important issues for the two countries remain unresolved, but the public perceives that the most important issues were under-addressed during the summit.

First, as shown in the previous Asan report on Korean attitudes toward China, a majority (53.6%) of the Korean public identified North Korea’s nuclear program as the most important agenda item to be discussed between the two countries. This coincides with a plurality (34.3%) stating that China should play the most important role in denuclearizing North Korea.

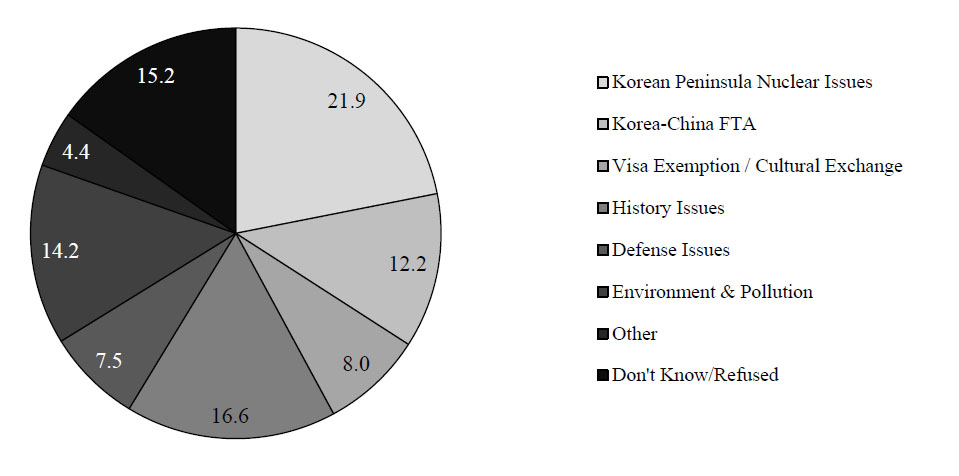

However, according to the post-summit survey, just 21.9 percent stated that they felt the denuclearization of North Korea was given the most attention during the summit (Figure 6). The second most cited issue was Korea-China cooperation on history issues, with 16.6 percent stating the felt it was the top agenda item. (In the pre-summit survey, 12.8% stated that this issue should receive top billing placing it third on the list.)

Figure 6: Perceived Priorities of the Summit

The issue of history was not brought up in the press conference at the close of the first day of the summit. However, the issue was emphasized by President Xi during his speech at Seoul National University. In response to the questions this created, Ju Chul-ki, Korea’s senior foreign affairs and security adviser, said that the two presidents expressed mutual concern about Japan’s reinterpretation for its right to collective self-defense and recent review of the Kono Statement in private meetings. This somewhat controversial press briefing by Mr. Ju grabbed the attention of the public.

Can China be Trusted?

In the Asan Report on China, that the fundamental perception of China has not changed was a point of emphasis. Although numerous survey results indicate that the favorability of China has dramatically improved, the underlying threat perceptions and mistrust of China have changed little. These metrics were followed up on after the summit in Seoul.

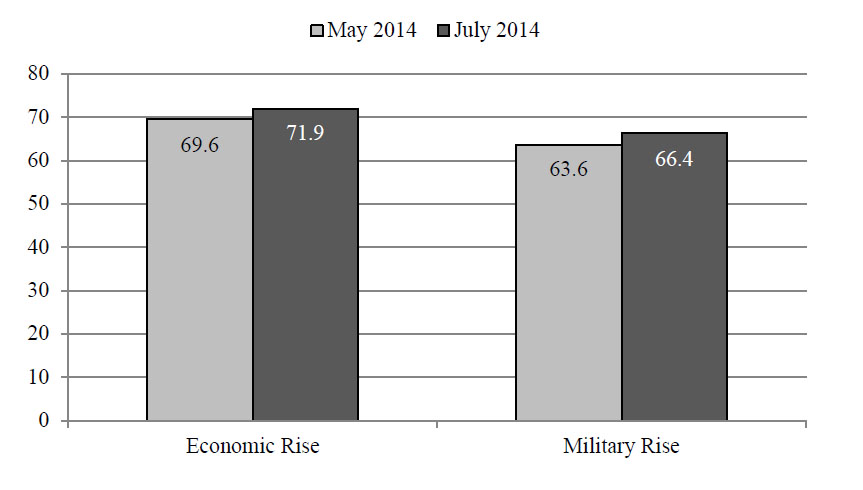

The data shows virtually no change in these threat perceptions. When asked about China’s economic rise, 69.6 percent of the Korean public stated that it was a threat (Figure 7). This was only a 2.3pp decline from the previous poll conducted in May. In terms of China’s military rise, 63.6 percent of respondents saw it as a threat. This was a 2.8pp decrease from the May result. Both declines are within the margin of error, illustrating no change in the Korean public’s threat perceptions of China’s economic and military rise after the summit.

Figure 7: Threat Perceptions of China

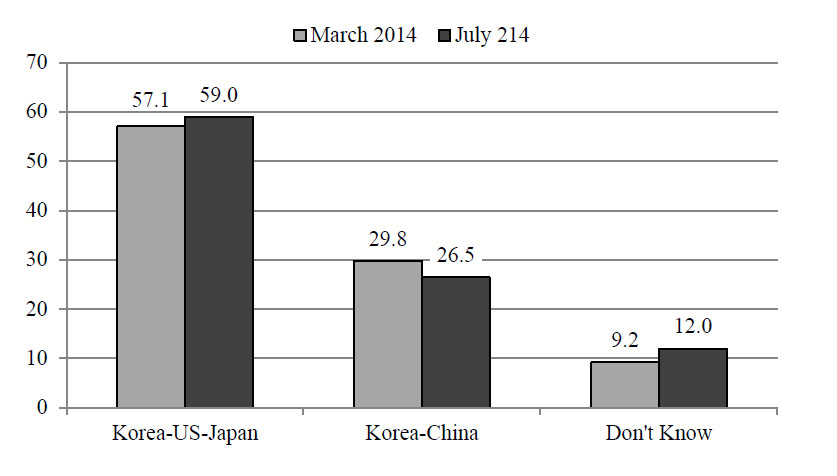

The July 2014 summit fell short in altering Korean views on preferred security cooperation relationships. A clear majority (59.0%) continued to cite Korea-US-Japan trilateral security cooperation as more important—up slightly from 57.1 percent who stated the same in March 2014 (Figure 8). There was a corresponding decline for those that cited Korea-China security cooperation as more important (26.5%).

Figure 8: Preferred Security Cooperation

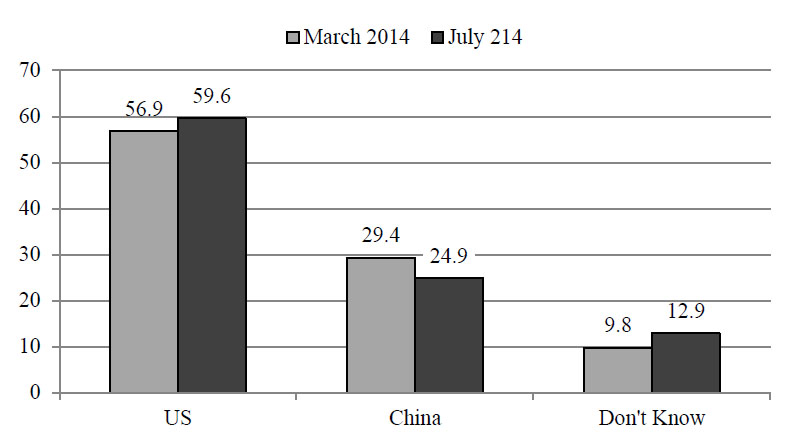

A similar tendency is found in the Korean public’s opinion on cooperative partners. In the March survey, 56.9 percent cited the United States as the preferred cooperative partner while 24.9 percent cited China (Figure 9). Following President Xi’s visit, those numbers changed little. In July, 59.6 percent stated that the United States was the preferred cooperative partner versus 24.9 percent that cited China. China’s continued calls for the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula and resumption of the Six-Party Talks was clearly not enough to change the Korean public’s collective mind. In addition, this casts doubt upon the claims that Korea is now leaning toward China. As the data shows, the Korean public has not changed.

Figure 9: Preferred Cooperative Partner

Irreconcilable Differences: Korean and Chinese Dreams

President Xi said that the Chinese and Korean dreams were one and the same. Both countries cemented a future of further cooperation, particularly in the economic field. There was also a consensus for the importance of cultural exchanges and public diplomacy. But the summit in Seoul seems to have accentuated the irreconcilable differences between the two. Most importantly, the Chinese delegation did not bring the gift that most Koreans had wished for. As previous survey results indicated, North Korea’s nuclear weapons program was the most pressing issue and numerous Korean eyes were focused on how President Xi would deal with it. His reaffirmation of China’s position—the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula—was a disappointment. The Korean government tried to emphasize that China was now ‘firmly opposed’ to it—a much stronger tone from the previous being ‘wary’ of it—to little effect.

Unlike the Korean government, the Korean public dared not misinterpret it. The summit did not bring what Koreans most wished for, and the public clearly perceived this. The survey results demonstrate that the Korean public is not swayed by and will not lean toward China unless there is a meaningful step forward from by China on North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. Friendship and nice atmospherics do not change the fundamental attitude. Japan’s criticism that Korea is turning to China at the expense of relations with the United States and Japan is not supported by the data.

Gabriel A. Almond and Walter Lippman once said that the level of public knowledge is low and public opinion is sometimes dangerously erratic. Thus, it need not be considered in foreign policy making. Some revisionists such as Page and Shapiro later argued that public can be reasonable enough to be considered as the ‘rational public’ (Page and Shapiro 1988).

This time, the Korean public is rational. It is probably time for the government to listen.

Survey Methodology

Asan Annual Surveys

2012

Sample size: 1,500 respondents over the age of 19

Margin of error: ±2.5% at the 95% confidence level

Survey method: RDD for mobile and landline telephones and online survey

Period: September 24 – November 1, 2014

Organization: Millward Brown Media Research

2013

Sample size: 1,500 respondents over the age of 19

Margin of error: ±2.5% at the 95% confidence level

Survey method: RDD for mobile and landline telephones and online survey

Period: September 4 – September 27, 2013

Organization: Millward Brown Media Research

Asan Daily Poll

2012

Sample size: 1,000 respondents over the age of 19

Margin of error: ±3.1% at the 95% confidence level

Survey method: RDD for mobile and landline telephones

Period: See report for specific dates of surveys cited.

Organization: Research & Research

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter