Introduction

A dark cloud hangs over South Korea and Japan as they struggle to put the past behind them. During the second half of 2018, the Moon Jae-in administration began the process of dissolving the Reconciliation and Healing Foundation, which was established to disburse funds meant to compensate the South Korean comfort women as part of an agreement signed in December 2015. In June 2019, the Seoul High Court ordered the Nippon Steel and Sumitomo Metal Company to compensate the plaintiffs of forced laborers who were conscripted to work for the company during 1942~45. The Japanese government maintains that the forced labor issue was settled under the 1965 treaty between the two countries. Finally, there was the radar lock-on incidence of December 20, 2018, when a South Korean Navy destroyer allegedly targeted the Japanese P-1 maritime patrol aircraft.

The two countries remain at loggerheads about all of these issues. The latest round of diplomatic escalation resulted in Japan imposing trade restrictions on South Korea, including the exclusion of South Korea from its whitelist of favored trade partners. South Korea, in response, also moved to exclude Japan from its own whitelist and announced its intent to not renew the General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA).

The Asan Institute for Policy Studies conducted a poll in August 2019 (19-21) to assess South Korean public attitudes about the deteriorating relations between South Korea and Japan. The findings indicate that

■ South Korean public views about Japan appear to be at a near all-time low. The average favorability for Japan (0= least favorable, 10= most favorable) is at its lowest point since 2017 at 2.3. Prime Minister Abe’s favorability was also very low at 1.1.

■ In general, South Koreans support the government’s policy on Japan. A little over 56% of respondents approve the government’s handling of South Korea’s relations with Japan, while approximately 37% disapprove. Ideological differences appear to matter with over 79% of progressives expressing support for the government’s response in contrast to nearly 34% of conservatives doing the same.

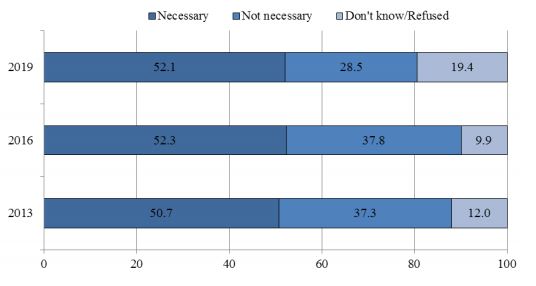

■ Many South Koreans, however, also affirm the importance of security cooperation between South Korea and Japan. Slightly over 52% of respondents acknowledge the value of security cooperation between South Korea and Japan. This finding is consistent with other results reported in 2013 (50.7%) and 2016 (52.3%).

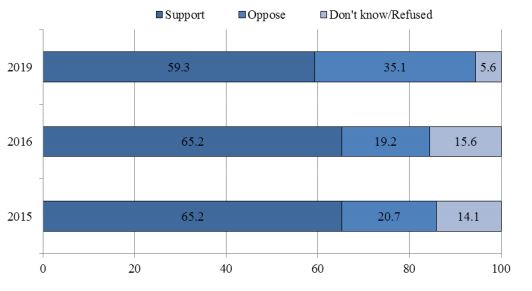

■ In addition, about 59% agree that South Korea and Japan should take a two-track approach to the bilateral relationship. This is also consistent with three other surveys conducted since 2015, in which nearly two-thirds of the South Korean public supported the two-track approach (65.2% in 2015-16).

The above findings illustrate the intricacies and nuances of South Korea-Japan relations. While history issues will remain as a challenge for these two uneasy neighbors, the South Korean public appears to acknowledge the value of cooperation and improved bilateral ties.

Favorability of Japan and Prime Minister Abe

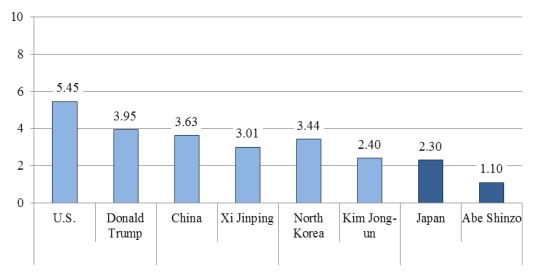

For seasoned observers, it is not at all surprising to find South Korean perception of Japan to be negative. The extent to which South Koreans have expressed negative feelings about Japan in recent months, however, is striking. According to the August 2019 survey, the average favorability ratings for Japan and Prime Minister Abe (0= least favorable, 10= most favorable) are 2.3 and 1.1, respectively (See Figure 1). The average favorability of Japan is comparably lower than that of the United States (5.45), China (3.63), and North Korea (3.44). And the favorability for Prime Minister Abe is lower than that of President Trump (3.95), Xi Jinping (3.01), and Kim Jong-un (2.4).

Two factors appear to be at work. In 2018, we saw a dramatic improvement in South Korean public opinion about North Korea and Kim Jong-un. This can be attributed to the flurry of diplomatic engagements between the two Koreas and the United States. Public attention and spotlight appears to have focused less on Japan and more on North Korea. Secondly, we saw little improvement in bilateral relations between South Korea and Japan during the same period. The recent fall-out in ROK-Japan relations resulting from the forced labor ruling and Japan’s trade restrictions led to South Korea taking corresponding measures which resulted in a nationwide boycott against Japanese products and South Korea’s refusal to renew GSOMIA. South Korea and Japan have been unable to resolve these issues.

Figure 1. Favorability of Neighboring Countries and Leaders in August 20191 (0~10 point)

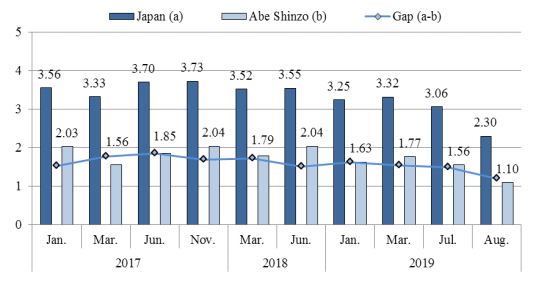

The decline in favorability ratings of Japan and Prime Minister Abe appears to reflect deteriorating relations between South Korea and Japan. Japan’s average favorability, which was 3.32 points in March 2019, fell sharply in July (3.06) and August (2.3). Prime Minister Abe’s average favorability also fell sharply from 1.77 in March to 1.56 and 1.1 in July and August, respectively (See Figure 2).

Figure 2. Favorability of Japan and Prime Minister Abe Shinzo2 (0~10 point)

South Korean Government Policy on Japan

Putting aside the Comfort Women Agreement of 2015, relations between South Korea and Japan have never really fared well since Prime Minister Abe assumed office in 2012. Japan’s rightward leanings, as well as the recent internal debate about a possible revision of the Japanese constitution, have raised some concerns among observers in South Korea. Recent steps taken by the Moon administration have also done little to improve relations.

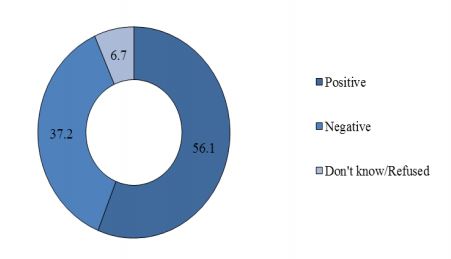

When asked to assess the Moon administration’s policy response regarding Japan, approximately 56% of those surveyed approves. About 37% of respondents disapprove (See Figure 3). Since the survey was taken before the Blue House announced its intention to end GSOMIA, these figures may have changed. But it is worth noting that the gap between support and opposition is approximately 20% points.

Figure 3. Public View of Policy Responses toward Japan3 (%)

When the respondents were asked in a follow-up question why they support the government’s policy on Japan, 36.5% state that the current situation is an opportunity to reduce South Korea’s dependence on Japan. Approximately 30% state that South Korea needs to respond firmly to Japan. 15.5% state that they see the government also pursuing diplomatic solutions, and about 11% say that the government’s policy is consistent with the domestic public opinion and national sentiment.

If asked why the respondent opposes the government’s policy on Japan, about 34% say that the government failed to consider other diplomatic options. Nearly 28% state that the government’s policy would negatively impact the South Korean economy. A little fewer than 14% state that South Korea is also responsible for the dispute between South Korea and Japan, while 10.5% express concern about US-Japan security cooperation.

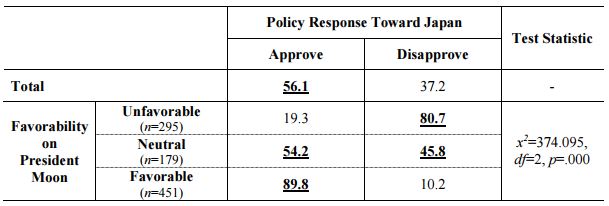

Upon closer inspection, we see the existence of some relationship between support for the administration’s policy on Japan and President Moon’s favorability (See Table 1). Approximately 90% of those who favor President Moon also support the administration’s policy towards Japan. Among those who are neutral, only 54% support the government. Among those that do not favor President Moon, only a little over 19% support the administration’s Japan policy.

Table 1. Evaluation of Policy by President Moon’s Favorability (%)4

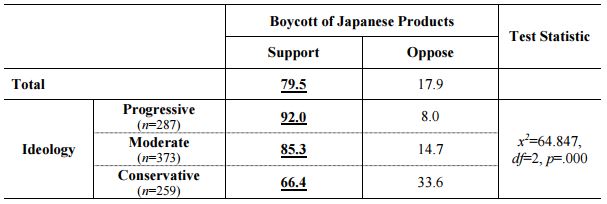

Ideological orientation also seems to matter. Approximately 79% of self-identified progressives support the government’s policy compared to 62% of conservatives. Both progressives and moderates also support the nationwide boycott campaign against Japanese products and services by 92% and 85%, respectively (See Table 2). A little over 60% of conservatives support the boycott.

Table 2. Boycott of Japanese Goods by Ideology (%)5

Prospects for South Korea-Japan Cooperation

The most recent controversy surrounding the ROK-Japan relations is the Blue House’s announcement that South Korea will allow GSOMIA to expire in November. The U.S. government has been one of the most vocal critics of this decision. The reason is simple – the dissolution of GSOMIA not only weakens security cooperation among US-led allies against regional adversaries like China and North Korea but it also creates problems in the U.S. grand strategy and approach to the Indo-Pacific.6 Robust trilateral cooperation between the U.S., ROK, and Japan is the foundation upon which the U.S. would like to push ahead with the Indo-Pacific strategy with regional partners, like Australia, Indonesia, New Zealand, and India, among others.

How do South Koreans see the issue of ROK-Japan security cooperation? According to our data, more than half acknowledge the importance of security cooperation between South Korea and Japan. This finding is consistent with other surveys conducted in 2013 and 2016. In fact, our most recent study suggests that South Koreans today are least likely to downplay the necessity of security cooperation between South Korea and Japan. Only 28.5% of respondents say that security cooperation is not necessary. Nearly 20% of South Koreans are non-committal about their support for ROK-Japan security cooperation (See Figure 4).

Figure 4. Necessity of ROK-Japan Security Cooperation Including GSOMIA7 (%)

Together, the above findings show that many Koreans support the government’s approach to Japan-related matters, but they also understand the importance of security cooperation with Japan. Of those respondents (n=521) who acknowledge the necessity of security cooperation between South Korea and Japan, a little over 35% state that “security should be treated separately from economic matters.” 31% emphasize the importance of “ROK-US-Japan trilateral cooperation.” Of those individuals who say that ROK-Japan cooperation is not important (n=285), a large majority (70%) state that this is because “Japan cannot be trusted.”

Two-Track Approach

Given the above findings, it is not at all surprising to see the South Korean public supporting the so-called two-track approach to ROK-Japan relations. In three surveys conducted since 2015, around 60% supported treating history matters separately from non-history related issues (i.e., security and economy) in managing South Korea-Japan relations (See Figure 5). One notable trend is that there is a marked increase in the number of those respondents who opposed the two-track approach. In the past, approximately 20 percent (20.7% in 2015 and 19.2% in 2016) of those surveyed opposed the two-track approach. Our most recent survey shows this figure increasing to 35.1 percent.

It is noteworthy; nonetheless, that 59% of respondents support the two-track approach. Of those that support the two-track approach (n=593), nearly 40% cite “economic benefits” as the main reason for doing so. Approximately 29% identify “security” while 16% mention “shared values” as the principal reasons for supporting the two-track approach. Finally, a little over 10% say that “history issue is difficult to resolve.” Of those who do not support the two-track approach (n=351), approximately 55% say that “it is impossible to ignore history when considering relations with Japan.” 18% claim that South Korea and Japan “do not share similar values” and about 12% state that “Japan is not very helpful in resolving security issues.”

Figure 5. Opinion on the Two-Track Approach8 (%)

Ideological Orientation on Security Cooperation and Two-Track Approach

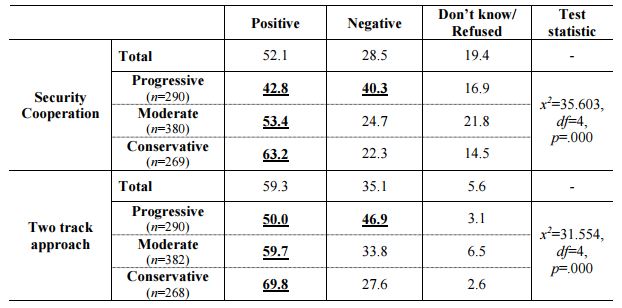

We noted some interesting ideological differences on questions related to security cooperation with Japan (See Table 3). For instance, self-identified progressives appear split down the middle on the issue of security cooperation between South Korea and Japan. Approximately 43% support and over 40% oppose ROK-Japan security cooperation. About 53% of moderates and over 63% of conservatives support ROK-Japan security cooperation.

Similar patterns can also be found on the issue of the two-track approach. 50% of progressives support the two-track approach, while nearly 47% oppose. Almost 60% of moderates and 70% of conservatives support the two-track approach.

Table 3. Public Views on ROK-Japan Cooperation by Self-identified Ideology (%)9

Conclusion

While there appears to be no end in sight to the feud over history between South Korea and Japan, there is a silver lining. Our most recent survey suggests that the South Korean public understands the value of genuine cooperation and reconciliation between South Korea and Japan.

History is an important problem in ROK-Japan relations. According to one poll conducted at the end of May, nearly 87% of South Koreans stated that the Japanese government must issue another apology on the comfort women issue. Only 11% of Japanese agreed with this sentiment. Clearly, this issue requires time and careful management. It also requires separate treatment from other outstanding issues in bilateral relations. More than half of the South Korean public understands that history must be treated separately from other bilateral issues in order to best manage relations between South Korea and Japan.

The results of our latest survey suggest the following with respect to ROK-Japan relations. First, many South Koreans place a high premium on ROK-Japan cooperation. There is also robust support for the two-track policy and security cooperation, such as GSOMIA. If GSOMIA cannot be revamped, both governments should begin to explore new areas of cooperation to deepen and broaden the relationship in new ways. A more proactive approach to participation in the US-led Indo-Pacific strategy can be an important step in this direction. Second, President Moon must look for opportunities to reopen dialogue with Prime Minister Abe. While Japan has not been as receptive to South Korean offers for dialogues, Seoul should not give up the possibility that an opportunity may arise for both countries to address common challenges, such as the North Korean nuclear threat. Finally, it is worth noting that many of these history-related issues are timed to Japan’s parliamentary elections this year and South Korea’s parliamentary election early next year. Both countries should exercise discipline and begin to think more broadly about each other’s national interests rather than narrow partisan interests timed to the domestic political cycles in each country.

Appendix

Survey Methodology

Sample size: 1,000 respondents over age of 19

Margin of error: ±3.1% points at the 95% confidence level

Survey method: Random Digit Dialing (RDD) for mobile and landline phones using Computer Assisted Telephone Interview (CATI)

Period: See the endnotes of each figure/table

Organization: Research & Research

The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

- 1. Asan Poll(August 19-20 2019).

- 2. Asan Poll(January 2-4, March 6-8, June 1-3, November 14-16 2017; March 21-22, June 18-20 2018; January 7-9, March 19-20, July 9-10, August 19-21 2019).

- 3. Asan Poll(August 19-20 2019).

- 4. Asan Poll(August 19-20 2019). Responses of “don’t know” and “refused to answer” were excluded in an analysis.

- 5. Asan Poll(August 19-20 2019). Responses of “don’t know” and “refused to answer” were excluded in an analysis.

- 6. Frank Januzzi. “Out of Tune: Japan-ROK Tension and U.S. Interests in Northeast Asia,” Brief for Congressional Outreach. NBR. October 9, 2019; Indo-Pacific Strategy Report: Preparedness, Partnerships, and Promoting a Networked Region,” The U.S. Department of Defense. June 1, 2019.

- 7. Asan Poll (December 29-31 2013, November 22-24 2016, August 19-21 2019). Those who saw the security cooperation as necessary chose the reasons such as “the security cooperation between South Korea and Japan can check the rise of China” (13.1%) and “it is useful to refer Japan’s military information to counter North Korean nuclear threat” (12.6%). However, those who saw the security cooperation as unnecessary selected the reasons such as “to counter Japan’s economic retaliation” (14.1%), “it is not useful to refer Japan’s military information to counter North Korean nuclear threat” (8.6%), and “it might have a negative impact on the ROK-China relations” (2.9%).

- 8. Asan Poll(June 5-6 2015; January 4-5 2016; August 19-20 2019).

- 9. Asan Poll(August 19-20 2019). In the questions about the ROK-Japan security cooperation and the two track approach toward Japan, the responses of “necessary” and “support” were categorized into “positive” and the opposite responses such as “unnecessary” and “oppose” were categorized into “negative”.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter